White Cliffs of Dover

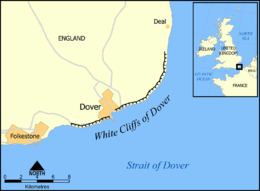

The White Cliffs of Dover, part of the North Downs formation, is the region of English coastline facing the Strait of Dover and France. The cliff face, which reaches a height of 350 feet (110 m), owes its striking appearance to its composition of chalk accented by streaks of black flint. The cliffs, on both sides of the town of Dover in Kent, stretch for eight miles (13 km). A section of coastline encompassing the cliffs was purchased by the National Trust in 2016.[1]

| White Cliffs of Dover | |

|---|---|

Viewed from the Strait of Dover | |

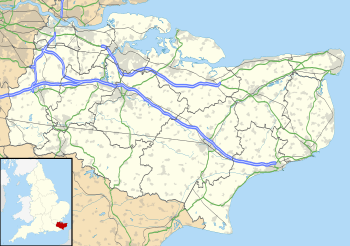

Location in Kent | |

| Location | Kent, England |

| OS grid | TR326419 |

| Coordinates | 51.14°N 1.37°E |

The cliffs are part of the Dover to Kingsdown Cliffs Site of Special Scientific Interest[2] and Special Area of Conservation.[3]

Location

The cliffs are part of the coastline of Kent in England between approximately 51°06′N 1°14′E and 51°12′N 1°24′E, at the point where Great Britain is closest to continental Europe. On a clear day they are visible from the French coast. The chalk cliffs of the Alabaster Coast of Normandy in France are part of the same geological system.

The White Cliffs are at one end of the Kent Downs designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[4] In 1999 a sustainable National Trust visitor centre was built in the area. The Gateway building, designed by van Heyningen and Haward Architects, houses a restaurant, an information centre on the work of the National Trust, and details of local archaeology, history and landscape.[5]

Geology

About 70 million years ago Great Britain and much of Europe were submerged under a great sea. The sea bottom was covered with white mud formed from fragments of coccoliths, the skeletons of tiny algae that floated in the surface waters and sank to the bottom during the Cretaceous period and, together with the remains of bottom-living creatures, formed muddy sediments. It is thought that the sediments were deposited very slowly, probably half a millimetre a year, equivalent to about 180 coccoliths piled one on top of another. Up to 500 metres of sediments were deposited in some areas.[6] The weight of overlying sediments caused the deposits to become consolidated into chalk.[7]

Subsequent earth movements related to the formation of the Alps raised the sea-floor deposits above sea level. Until the end of the last glacial period, the British Isles were part of continental Europe, linked by the unbroken Weald-Artois Anticline, a ridge that acted as a natural dam to hold back a large freshwater pro-glacial lake, now submerged under the North Sea. The land masses remained connected until between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago when at least two catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods breached the anticline and destroyed the ridge that connected Britain to Europe. A land connection across the southern North Sea existed intermittently at later times when periods of glaciation resulted in lower sea levels.[8] At the end of the last glacial period, around 10,000 years ago, rising sea levels finally severed the last land connection.[9]

The cliffs' chalk face shows horizontal bands of dark-coloured flint which is composed of the remains of sea sponges and siliceous planktonic micro-organisms that hardened into the microscopic quartz crystals. Quartz silica filled cavities left by dead marine creatures which are found as flint fossils, especially the internal moulds of Micraster echinoids. Several different ocean floor species such as brachiopods, bivalves, crinoids, and sponges can be found in the chalk deposits, as can sharks' teeth.[10]

In some areas, layers of soft, grey chalk known as a hardground complex can be seen. Hardgrounds are thought to reflect disruptions in the steady accumulation of sediment when sedimentation ceased and/or the loose surface sediments were stripped away by currents or slumping, exposing the older hardened chalk sediment. A single hardground may have been exhumed 16 or more times before the sediments were compacted and hardened (lithified) to form chalk.[10]

Erosion and the effects of climate change

The White Cliffs of Dover have been eroding slowly but in the past 150 years they have been eroding ten times faster than they did before.[11] This is because of the thinning of beaches that separate the cliffs from the sea and the fact that the cliffs themselves are made up of coccolithophore shells, which are chalk-based and unusual in forming calcium carbonate shells which eventually sink to the seabed to form chalky deposits that are vulnerable to erosion.[12] The change is likely due to the construction of sea walls and groynes, and stronger storms hitting the coastline due to climate change and the rise of CO

2 in the ocean.[11] Scientists say that the English Channel has eaten away at the cliffs at a rate of 8.7 inches to just over a foot. A thousand years ago, that rate was three-quarters of an inch to 2.3 inches per year.[11]

Over the years, the cliffs began to crumble as well and there have been sudden cliff falls due to the erosion of the chalk.[13] In 2001, a large chunk of the cliff edge, as large as a football pitch, fell into the Channel.[14] Another large section collapsed on 15 March 2012.[15] As mentioned before, coccolithophores shells have increased in the ocean due to the increase of carbon dioxide in the sea. The ocean absorbs CO

2 and while that happens the pH drops and the water becomes more acidic. One of the forms affected by this is a type of phytoplankton called coccolithophores. Ocean acidification can damage corals, such as those in the Great Barrier Reef. This can affect the coral strength and lead to them breaking more easily and more often. Coccolithophores make up the White Cliffs of Dover, and because of ocean acidification, it is causing them to erode at a faster rate.[16][11][17] All together, this could affect the wildlife on the cliffs and the cliffs themselves, for if they continue to erode, they could disappear altogether.[11][17][18][13][16]

The White Cliffs are eroding because of the rise of sea levels and the decrease of pH levels in the ocean due to the rise of CO

2 in the ocean.[19] The only way this can be solved is if the beaches that separate the cliffs from the ocean are well maintained and the cliffs themselves are cared for.[17] If the level of CO

2 in the ocean continues to rise, then the eroding of the cliffs will continue to increase in the years to come.

Ecology

The chalk grassland environment above the cliffs provides an excellent environment for many species of wild flowers, butterflies and birds, and has been designated a Special Area of Conservation and a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Rangers and volunteers work to clear invasive plants that threaten the native flora. A grazing programme involving Exmoor ponies has been established to help to clear faster-growing invasive plants, allowing smaller, less robust native plants to survive.[20] The ponies are managed by the National Trust, Natural England, and County Wildlife Trusts to maintain vegetation on nature reserves.[21]

The cliffs are the first landing point for many migratory birds flying inland from across the English Channel. After a 120-year absence, in 2009 it was reported that ravens had returned to the cliffs. Similar in appearance but smaller, the jackdaw is abundant. The rarest of the birds that live along the cliffs is the peregrine falcon. In recent decline and endangered, the skylark also makes its home on the cliffs.[22] The cliffs are home to fulmars, which resemble gulls, and to colonies of black-legged kittiwake, a species of gull. Bluebird, as mentioned in the classic World War II song "(There'll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover" is an old country name for swallows and house martins, which make an annual migration to continental Europe, many of them crossing the English Channel at least twice a year.

Among the wildflowers are several varieties of orchids, the rarest of which is the early spider orchid, which has yellow-green to brownish green petals and looks like the body of a large spider. The oxtongue broomrape is an unusual plant that lives on the roots of a host plant. It has yellow, white, or blue snapdragon-like flowers and about 90 per cent of the UK's population is found on the cliffs. Viper's-bugloss, a showy plant in vivid shades of blue and purple with red stamens, also grows along the cliffs.[22] In his play King Lear, Shakespeare mentions rock samphire, an edible plant that grows on the cliffs. It was collected by gatherers who hung from ropes down the cliff: "Half-way down / Hangs one that gathers samphire; dreadful trade!" (Act IV, Scene VI). This refers to the dangers involved in collecting rock samphire on sea cliffs.

The abundance of wildflowers provides homes for about thirty species of butterfly. The rare Adonis blue can be seen in spring and again in autumn. Males have vibrant blue wings lined with a white margin, whereas the females are a rich chocolate brown. This species' sole larval food plant is the horseshoe vetch and it has a symbiotic relationship with red or black ants. The eggs are laid singly on very small foodplants growing in short turf. This provides a warm microclimate, suitable for larval development, which is also favoured by ants. The caterpillar has green and yellow stripes to provide camouflage while it feeds on vetch. The ants milk the sugary secretions from the larval "honey glands" and, in return, protect the larvae from predators and parasitoids, even going so far as to bury them at night. The larvae pupate in the upper soil, and continue to be protected by the ants, often in their nests, until the adults emerge in the spring or autumn.[23]

Similar in appearance, but more abundant, is the chalk hill blue, a chalk grassland specialist that can be seen in July and August.[24][22] Threatened species include the silver spotted skipper and straw belle moth. The well-known red admiral can be seen from February until November. The marbled white, black and white with a white wing border, can be seen from June to August.

Samphire Hoe Country Park

Samphire Hoe Country Park is a nature reserve on a new piece of land created from the rock excavated during the construction of the Channel Tunnel. It covers a 74-acre (30 ha) site at the foot of Shakespeare Cliff, between Dover and Folkestone. There is an education shelter with a classroom and exhibition area. Staff and volunteers are available to answer questions and provide information about the wildlife in the reserve. The building's design incorporates eco-construction criteria. Samphire, a wild edible plant, grew on the cliffs and was gathered by hanging from ropes over the cliff's edge. Shakespeare Cliff was named after the reference to this "dreadful trade" in Shakespeare's play King Lear (Act 4, Scene 6, Lines 14-15).

History

A possible Iron Age hillfort has been discovered at Dover, on the site of the later castle.[25] The area was also inhabited during the Roman period, when Dover was used as a port. A lighthouse survives from this era, one of a pair at Dover which helped shipping navigate the port. It is likely the area around the surviving lighthouse was inhabited in the early medieval period as archaeologists have found a Saxon cemetery here, and the church of St Mary in Castro was built next to the lighthouse in the 10th or 11th century.[26] It is thought that the Old English name for Britain, Albion, was derived from the latin albus (meaning 'white') as an allusion to the white cliffs.[27]

Dover castle

Dover Castle, the largest castle in England,[28] was founded in the 11th century. It has been described as the "Key to England" owing to its defensive significance throughout history.[29][30] The castle was founded by William the Conqueror in 1066 and rebuilt for Henry II, King John, and Henry III. This expanded the castle to its current size, taking its curtain walls to the edge of the cliffs. During the First Barons' War the castle was held by King John's soldiers and besieged by the French between May 1216 and May 1217. The castle was also besieged in 1265 during the Second Barons' War. In the 16th century, cannons were installed at the castle, but it became less important militarily as Henry VIII had built artillery forts along the coast. Dover Castle was captured in 1642 during the Civil War when the townspeople climbed the cliffs and surprised the royalist garrison, giving a symbolic victory against royal control. Towards the end of the war many castles were slighted, but Dover was spared.[31]

The castle had renewed importance from the 1740s as the development of heavy artillery made capturing ports an important part of warfare. During the Napoleonic Wars, in particular, the defences were remodelled and a series of tunnels were dug into the cliff to act as barracks, adding space for an extra 2,000 soldiers. The tunnels mostly lay abandoned until the Second World War.[32]

Second World War

The cliffs have great symbolic value in Britain because they face towards continental Europe across the narrowest part of the English Channel, where invasions have historically threatened and against which the cliffs form a symbolic guard. The National Trust calls the cliffs "an icon of Britain", with "the white chalk face a symbol of home and wartime defence."[33] Because crossing at Dover was the primary route to the continent before the advent of air travel, the white line of cliffs also formed the first or last sight of Britain for travellers. During the Second World War, thousands of allied troops on the little ships in the Dunkirk evacuation saw the welcoming sight of the cliffs.[34] In the summer of 1940, reporters gathered at Shakespeare Cliff to watch aerial dogfights between German and British aircraft during the Battle of Britain.[35]

- Vera Lynn, known as "The Forces' Sweetheart" for her 1942 wartime classic "(There'll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover" celebrated her 100th birthday in 2017. That year she led a campaign for donations to buy 170 acres (0.7 km2) of land atop Dover's cliffs when it was feared that they might be sold to developers; the campaign met its target after only three weeks. The National Trust, which owns the surrounding areas, plans to return the land to a natural state of chalk grassland and preserve existing military structures from the Second World War.[36]

Dover Museum

Dover Museum was founded in 1836. Shelled from France in 1942 during the Second World War, the museum lost much of its collections, including nearly all its natural history collections. Much of the surviving material was left neglected in caves and other stores until 1946. In 1948 a temporary museum was opened and in 1991 a new museum of three storeys, built behind its original Victorian façade, was opened. In 1999, a new gallery on the second floor centred on the Dover Bronze Age Boat was opened.[37]

South Foreland Lighthouse

.jpg)

South Foreland Lighthouse is a Victorian-era lighthouse on the South Foreland in St. Margaret's Bay, which was once used to warn ships approaching the nearby Goodwin Sands. Goodwin Sands is a 10-mile-long (16 km) sandbank at the southern end of the North Sea lying six miles (10 km) off the Deal coast. The area consists of a layer of fine sand approximately 82 ft (25 m) deep resting on a chalk platform belonging to the same geological feature that incorporates the White Cliffs of Dover. More than 2,000 ships are believed to have been wrecked on the Goodwin Sands because they lie close to the major shipping lanes through the Straits of Dover. It went out of service in 1988 and is now owned by the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty.

In song and literature

- The most famous reference in English literature to the White Cliffs is in Shakespeare's King Lear. In Act IV, Scene VI, Edgar persuades the blinded Earl of Gloucester that he is at the edge of a cliff at Dover. In Act IV, Scene I, Lines 72-4, Gloucester says, "There is a cliff, whose high and bending head looks fearfully in the confinèd deep: Bring me but to the very brim of it." Edgar then fools the Gloucester into thinking he is at the cliff edge and describes the scene: "Here's the place! – stand still – how fearful/ And dizzy 'tis, to cast one's eye so low ... half way down/Hangs one that gathers samphire: dreadful trade!/Methinks he seems no bigger than his head." (Act IV, Scene VI, Lines 11-16).[38]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- In 1851, English poet Matthew Arnold began his lyric poem Dover Beach by epitomizing the beauty of the Kent coast:

- The sea is calm tonight,

- The tide is full, the moon lies fair

- Upon the straits:- on the French coast, the light

- Gleams, and is gone: the cliffs of England stand,

- Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.[38]

- The verse novel The White Cliffs by Alice Duer Miller encouraged U.S. entry into World War II.

- The White Cliffs have long been a landmark for sailors. It is noted as such in the sea shanty Spanish Ladies:[39]

- "The first land we sighted was called the Dodman,

- Next Rame Head off Plymouth, off Portsmouth the Wight;

- We sailed by Beachy, by Fairlight and Dover,

- And then we bore up for the South Foreland light."

- On a Piece of Chalk was a lecture by Thomas Henry Huxley presented to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1868 and published later that year.[40] The piece reconstructs the geological history of Great Britain from a simple piece of chalk and demonstrates science as "organized common sense".[41]

Also referenced as the title of "Cliffs of Dover" by musician Eric Johnson

Gallery

Shakespeare Cliff, Dover ca. 1905

Shakespeare Cliff, Dover ca. 1905- Lighthouse in Dover

_20-04-2012_(7217044814).jpg) Dover Castle

Dover Castle.jpg) White Cliffs of Dover footpath

White Cliffs of Dover footpath Folkestone and Dover from the International Space Station, showing the White Cliffs and the tracks of ferries.

Folkestone and Dover from the International Space Station, showing the White Cliffs and the tracks of ferries. Vintage photo taken by Walter Mittelholzer, Swiss photographer and aviator, 1933.

Vintage photo taken by Walter Mittelholzer, Swiss photographer and aviator, 1933.

See also

- Albion, a name for Britain possibly derived from the colour of the cliffs

- Beachy Head

- Kap Arkona

- Møns Klint

- Seaford Head Nature Reserve

- Seven Sisters, Sussex

- Shakespeare Cliff Halt railway station

- South Downs

References

Citations

- "White cliffs of Dover to be bought by National Trust". BBC. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "Designated Sites View: Dover to Kingsdown Cliffs". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: Dover to Kingsdown Cliffs". Special Area of Conservation. Natural England. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty]". The White Cliffs Countryside Partnership. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Dawson, Susan (27 May 1999). "Visitor Centre, White Cliffs of Dover van Heyningen & Haward Architects". Architects' Journal.

- "White Cliffs of Dover Discover The White Cliffs". The Dover Museum.

- The Royal Institution (5 December 2012). "Helen Czerski - Coccolithophores and Calcium". YouTube. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- Professor Bryony Coles. "The Doggerland project". University of Exeter. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- Harris, C. S. "Chalk facts". Geology Shop.

- Shepard, Roy. "Discovering Fossils - Introducing the Paleontology of Great Britain: Dover (Kent)". Discovering Fossils. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/11/11/the-sea-is-swallowing-the-white-cliffs-of-dover-at-faster-rates-thanks-to-thinned-beachfronts/

- https://www.scienceworldreport.com/articles/51981/20161110/historic-white-cliffs-dover-vanish-study-reveals.htm

- https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/the-white-cliffs-of-dover/features/cliff-top-wildlife-

- Beard, Matthew (1 February 2001). "White cliffs of Dover go crashing into the Channel". The Independent. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- "BBC News - White Cliffs of Dover suffer large collapse". BBC News. 15 March 2012.

- https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/increased-co2-ocean-whats-risk

- https://phys.org/news/2016-11-england-white-cliffs-dover-eroding.html

- https://www.iol.co.za/news/white-cliffs-of-dover-climate-warning-1951762

- https://www.co2.earth/carbon-in-the-ocean#targetText=At%20present%2C%20just%20a%20quarter,As%20acidification%20increases%2C%20pH%20falls.&targetText=This%20would%20make%20the%20ocean,the%20past%20100%20million%20years.

- "National Trust at The White Cliffs of Dover". Kent Life. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Map of UK Conservation Grazing Schemes". Grazing Animals Project. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

• "Wildlife Conservation of Local Downland and Heathland". Sussex Pony Grazing and Conservation Trust. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

• "Grazing Exmoor ponies to protect County Durham flowers". BBC News. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2012. - "Cliff Top Wildlife". The National Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Adonis blue" (PDF). Butterfly Conservation. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Brereton, Tom M.; Warren, Martin S.; Roy, David B.; Stewart, Katherine (20 July 2007). "The changing status of the Chalkhill Blue butterfly Polyommatus coridon in the UK: the impacts of conservation policies and environmental factors". Journal of Insect Conservation. 12 (6): 629–638. doi:10.1007/s10841-007-9099-0. ISSN 1366-638X.

- "EN3775 Dover Castle, Kent". Atlas of Hillforts. 29 April 2018.

- Coad (2007), pp. 40–41

- Anon, Oxford Living Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, retrieved 30 April 2018

- Cathcart King (1983), p. 230

- Kerr (1984), p. 44

- Broughton (1988), p. 102

- Coad (2007), pp. 42–47

- Coad (2007), pp. 48–50

- "The White Cliffs of Dover". The National Trust. 1 November 2016.

- Wijs-Reed, Jocelyn (2012). I've Walked My Own Talk. Partridge Publishing. p. 212.

- Sperber (1998), p. 161

- "Dame Vera Lynn white cliffs of Dover campaign hits £1m". BBC News. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Press Releases Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "White Cliffs of Dover Discover The White Cliffs". The Dover Museum.

- Palmer (1986)

- Wolfle, Dael (12 May 1967). "Huxley's Classic of Explanation". Science. 156 (3776): 815–816. JSTOR 1722013.

- Huxley, Thomas. "On a piece of chalk". University of Adelaide. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

Bibliography

- Broughton, Bradford B. (1988), Dictionary of Medieval Knighthood and Chivalry, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-25347-8

- Cathcart King, David J. (1983), Catellarium Anglicanum: An Index and Bibliography of the Castles in England, Wales and the Islands. Volume I: Anglesey–Montgomery, Kraus International Publications

- Coad, Jonathan (2007), Dover Castle, English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-905624-21-8

- Kerr, Nigel (1984), A Guide to Norman Sites in Britain, Granada, ISBN 978-0-586-08445-8

- Palmer, Roy (1986), The Oxford Book of Sea Songs, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-214159-0

- Sperber, A. M. (1998), Murrow, His Life and Times, Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-1881-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to White Cliffs of Dover. |

.jpg)