Virginia Company

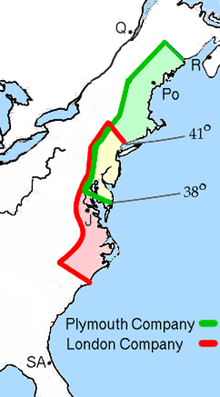

The Virginia Company refers collectively to two joint-stock companies chartered under James I on April 10, 1606[1][2][3] with the goal of establishing settlements on the coast of America.[4] The two companies are referred to as the "Virginia Company of London" (or the London Company) and the "Virginia Company of Plymouth" (or the Plymouth Company), and they operated with identical charters in different territories. The charters established an area of overlapping territory in America as a buffer zone, and the two companies were not permitted to establish colonies within 100 miles of each other. The Plymouth Company never fulfilled its charter, but its territory was claimed by England and became New England.

The areas of the Virginia Company founded and organized by Bartholomew Gosnold of Grundisburgh in Suffolk, England and granted an exclusive charter by James I to the London and Plymouth companies; also showing the overlapping (yellow) area granted to both companies | |

Formerly | Plymouth Company London Company |

|---|---|

Type | joint stock company |

As corporations, the companies were empowered by the Crown to govern themselves, and this right was passed on to the colony following the dissolution of the third Charter in 1621. The Virginia Company failed in 1624, but the right to self-government was not taken from the colony. The principle was thus established that a royal colony should be self-governing, and this formed the genesis of democracy in America.[5][6][7]:90–91

Differences between the two companies

The original charter by King James in 1606 did not mention a Virginia Company or a Plymouth Company; these names were applied somewhat later to the overall enterprise. The Charter of 1609 stipulates two distinct companies:

that they shoulde devide themselves into twoe collonies, the one consistinge of divers Knights, gentlemen, merchaunts and others of our cittie of London, called the First Collonie; and the other of sondrie Knights, gentlemen and others of the citties of Bristoll, Exeter, the towne of Plymouth, and other places, called the Second Collonie.[8]

The eastern seaboard of America was named Virginia from Maine to the Carolinas; Florida was under Spanish dominion.[9][10][11] As corporations, the companies were empowered by the Crown to govern the colonies; this right was not conferred onto the colonies themselves until the dissolution of the third Charter in 1621. The Virginia Company failed in 1624, but the right to self-government was not taken from the colony, and the principle was thus established that a royal colony should be self-governing, forming the genesis of democracy in America.[5][12] [7]:90–91

The London Company

By the terms of the charter, the London Company was permitted to establish a colony of 100 miles square between the 34th and 45th parallels, approximately between Cape Fear and Long Island Sound. It also owned a large portion of inland Canada. The company established the Jamestown Settlement on May 14, 1607 about 40 miles inland along the James River, a major tributary of the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. In 1620, George Calvert asked King James I for a charter for English Catholics to add the territory of the Plymouth Company. Also in 1609, a much larger Third Supply mission was organized. A new purpose-built ship named the Sea Venture was rushed into service without the customary sea trials. She became flagship of a fleet of nine ships, with most of the leaders, food, and supplies aboard. Aboard the Sea Venture were fleet Admiral George Somers, Vice-Admiral Christopher Newport, Virginia Colony governor Sir Thomas Gates, William Strachey, and businessman John Rolfe with his pregnant wife.

The Third Supply convoy encountered a hurricane which lasted three days and separated the ships from one another. The Sea Venture was leaking through its new caulking, and Admiral Somers had it driven aground on a reef to avoid sinking, saving 150 men and women but destroying the ship.[13] The uninhabited archipelago was officially named "The Somers Isles" after Admiral Somers.[14] The survivors built two smaller ships from salvaged parts of the Sea Venture which they named Deliverance and Patience.[15] Ten months later, they continued on to Jamestown, arriving on May 23, 1610 but leaving several men behind on the archipelago to establish possession of it. At Jamestown, they found that more than 85-percent of the 500 colonists had perished during the "Starving Time". The Sea Venture passengers had anticipated finding a thriving colony and had brought little food or supplies with them. The colonists at Jamestown were saved only by the timely arrival three weeks later of a supply mission headed by Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, better known as "Lord Delaware".

In 1612, The London Company's Royal Charter was officially extended to include the Somers Isles as part of the Virginia Colony. However, the isles passed to the London Company of the Somers Isles in 1615, which had been formed by the same shareholders as the London Company.

The Virginia Company of London failed to discover gold or silver in Virginia, to the disappointment of its investors. However, they did establish trade of various types. The biggest trade breakthrough came when colonist John Rolfe introduced several sweeter strains of tobacco[16] from the Caribbean,[17] rather than the harsh-tasting kind native to Virginia.[18] Rolfe's new tobacco strains led to a strong export for the London Company and other early English colonies and helped to balance a trade deficit with Spain.

The Jamestown Massacre devastated the colony in 1622 and brought unfavorable attention, particularly from King James I who had chartered the Company. There was a period of debate in Britain between Company officers who wished to guard the original charter, and those who wanted the Company to be disbanded. In 1624, the King dissolved the Company and made Virginia a royal colony.[19]

The charters of the Virginia Company of London

The First charter of the Virginia Company of London, 1606 The First Charter gave the company the authority to govern its own adventurers and servants through a ruling council in London composed of major shareholders in the enterprise. The members were nominated by the Company and appointed by the King. The council in England then directed the settlers to appoint their own local council, which proved ineffective. The council had to obtain approval from London for expenditures and laws, and limited the enterprise to 100 square miles.[20]

The Second charter of the Virginia Company of London, 1609 The Second Charter expanded the area of the enterprise from sea to sea and appointed a governor, because the local councils had proven ineffective. Governor Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr (known as Lord Delaware) sailed for America in 1610. The king delegated the governor of Virginia absolute power.[21]

The Third Charter of the Virginia Company of London, 1612 The Third Charter expanded territory eastward to include Bermuda and other islands.[22]

The Great Charter On November 18, 1618, Virginia Company officers Thomas Smythe and Edwin Sandys sent a set of instructions to Virginia Governor George Yeardley that are often referred to as "The Great Charter", though it was not issued by the King. This charter gave the colony self governance, which led to the establishment of a Council of State appointed by the governor and an elected General Assembly (House of Burgesses), and provided that the colony would no longer be financed by shares but by tobacco farming. The birth of representative government in the United States can be traced from this Great Charter, as it provided for self-governance from which the House of Burgesses and a General Council were created.[23][7]

Dissolution of the Charter The Jamestown Massacre in 1622 brought unfavorable attention to the colony, particularly from King James I who had originally chartered the Company. There was a period of debate in Britain between Company officers who wished to guard the original charter, and those who wanted the Company to be disbanded. In 1624, the King dissolved the Company and made Virginia a Royal colony.[19]

The Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company was permitted to establish settlements between the 38th and 45th parallels, roughly between the upper reaches of the Chesapeake Bay and the U.S.-Canada border. On August 13, 1607, the Plymouth Company established the Popham Colony along the Kennebec River in Maine. However, it was abandoned after about a year and the Plymouth Company became inactive. A successor company eventually established a permanent settlement in 1620 when the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, aboard the Mayflower.

Heraldry

The heraldic achievement of the "Virginian Merchants" was blazoned as follows:

Coat of Arms – Argent, a cross gules between four escutcheons, each regally crowned proper, the first escutcheon in the dexter chief, the arms of France and England quarterly; the second in the sinister chief, the arms of Scotland; the third the arms of Ireland; the fourth as the first.

Crest – On a wreath of the colors a maiden queen couped below the shoulders proper, her hair dishevelled, vested and crowned with an Eastern crown or.

Supporters – Two men in complete armor with their beavers [visors] open, on their helmets three ostrich feathers argent, each charged on the breast with a cross throughout gules, and each holding a lance proper in his exterior hand.

Motto – En dat Virginia quartam[24]/quintam[25] Behold, Virginia gives a fourth/fifth (dominion)

The motto recognized the colony's status alongside the king's other three or four dominions of England, Ireland, Scotland, and France (a heraldic fiction), and the Kingdom of Great Britain after the Acts of Union 1707.[26] There is no record, however, of these arms actually being granted.[24]

See also

- List of trading companies

Further reading

- Bemis, Samuel M. (2009) [1940]. The Three Charters of the Virginia Company of London. Louisiana State University Press, 1940 / reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Com.

References

- Paullin, Charles O, Edited by John K. Wright (1932). Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States. New York, New York and Washington, D.C.:: Carnegie Institution of Washington and American Geographical Society. pp. Plate 42.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Swindler, William F., Editor (1973–1979). Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions.' 10 Volumes. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications. pp. Vol. 10: 17–23.

- Van Zandt, Franklin K. (1976). Boundaries of the United States and the Several States; Geological Survey Professional Paper 909. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 92.

- How Virginia Got Its Boundaries, by Karl R Phillips

- Andrews, Charles M. (1924). The Colonial Background of the American Revolution. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 0-300-00004-9.

- "An Ordinance and Constitution of Treasurer and Company in England for a Council and Assembly in Virginia (1621)".

- Gayley, Charles Mills (1917). "Shakespeare and the Founders of Liberty in America". Internet Archive. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1600-1650/the-second-virginia-charter-1609.php

- "Charter of the Virginia Company of 1606".

- "Spanish Florida". Florida State, Dept of Library and Information Services.

- "Charter of 1609".

- "An Ordinance and Constitution of Treasurer and Company in England for a Council and Assembly in Virginia (1621)".

- Woodward, Hobson. A Brave Vessel: The True Tale of the Castaways Who Rescued Jamestown and Inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest. Viking (2009) pp. 32–50.

- A Discovery of The Barmudas, Sylvester Jordain

- Woodward, Hobson. A Brave Vessel: The True Tale of the Castaways Who Rescued Jamestown and Inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest. Viking (2009) pp. 92–94.

- "Welcome to Founders of America!". Archived from the original on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- Economics of Tobacco

- Virtual Jamestown

- The First Seventeen Years: Virginia, 1607–1624, Charles E. Hatch, Jr.

- "First Virginia Charter-1606".

- "Second Charter of the Virginia Company-1609".

- "The Third Charter of the Virginia Company of London-1612".

- "The Great Charter".

- Fox-Davies, Arthur. (1915) The Book of Public Arms. London: T. C. and E. C. Jack.

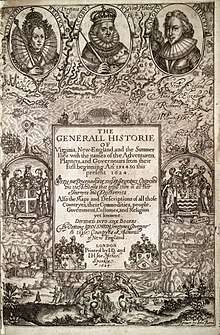

- As depicted on title page of: Smith, Captain John. (1624). The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles. London.

- n.a. (2019) "Questions About Virginia". Library of Virginia. Richmond.

- David A. Price, Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Heart of A New Nation, Alfred A. Knopf, 2003

External links

- First Charter of Virginia – 10 April 1606 O.S.; Julian Calendar (from Julius Caesar time) or 1 April 1606 N.S.; Gregorian Calendar (Current Civil Calendar.)

- Second Charter of Virginia

- Richard Frethorne's Letters, bilingual (english/french)