Vespro della Beata Vergine

Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin), SV 206 is a setting by Claudio Monteverdi of the evening Vespers service on Marian feasts, scored for soloists, choirs, and orchestra. Monteverdi's Vespers is an ambitious work both in scope and in variety of style and scoring, with a duration of around 90 minutes. Published in Venice (with a dedication to Pope Paul V dated 1 September) as Sanctissimae Virgini Missa senis vocibus ac Vesperae pluribus decantandae, cum nonnullis sacris concentibus, ad Sacella sive Principum Cubicula accommodata ("Mass for the Most Holy Virgin for six voices, and Vespers for several voices with some sacred songs, suitable for chapels and ducal chambers"), it is also called the Vespers of 1610 to distinguish it from other Vespers printed in 1640 and 1651.

| Vespro della Beata Vergine | |

|---|---|

| Vespers by Claudio Monteverdi | |

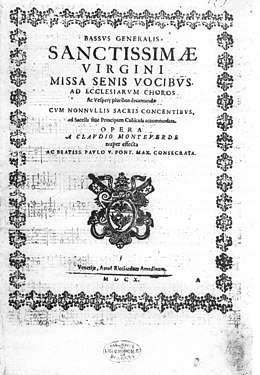

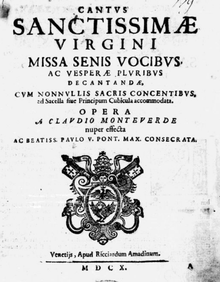

Title page of the "Bassus Generalis", one of the partbooks in which the Vespers were published in 1610 | |

| Catalogue | SV 206 and 206a |

| Text | Biblical and liturgical, including several psalms, a litany, a hymn and Magnificat |

| Language | Latin |

| Dedication | Pope Paul V |

| Published | 1610 in Venice |

| Duration | 90 minutes |

| Scoring |

|

Monteverdi composed the music while he was a court musician and composer of the Gonzaga, the dukes of Mantua. The text is compiled from several Biblical and liturgical texts in Latin. The 13 movements include the introductory Versicle Deus in adiutorium, five Psalms, four concertato motets and a vocal sonata on the "Sancta Maria" litany, several differently scored stanzas of the hymn "Ave maris stella", and a choice of 2 Magnificats. A church performance might also have included antiphons in Gregorian chant, unless these were meant to be replaced by the motets which are inserted between the psalms in the printed source. The composition demonstrates Monteverdi's ability to assimilate both the new seconda pratica and the old style of the prima pratica, building some movements on the traditional Gregorian plainchant as a cantus firmus. The composition is scored for up to ten vocal parts, and instruments including cornetts, violins, viole da braccio, and basso continuo.

No performance during the composer's lifetime can be positively identified from surviving documents,[1] though parts of the work might have been performed at the ducal chapels in Mantua (despite Monteverdi not being explicitly engaged there as a composer of sacred music) and at St Mark's in Venice, where he became director of music in 1613. The work received renewed attention from musicologists and performers in the 20th century, who have grappled with whether it is a planned composition in a modern sense as opposed to an anthology, with the liturgical role of the concerti and sonata, and with instrumentation, chiavette and other issues of performance practice. The first recording of excerpts from the Vespers was released in 1953.

History and context

Monteverdi in Mantua

Monteverdi, who was born in Cremona in 1567, was a court musician for the Dukes of Gonzaga in Mantua from 1590 to 1612. He began as a viol player under Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga,[2] and advanced to become his leader, maestro della musica, in late 1601.[3] He was responsible for the duke's sacred and secular music, in regular church services and soirées on Fridays and for extraordinary events.[4] During this time, the opera genre developed, first as court entertainment but later as public musical theatre.[5] The first work now considered as an opera is Jacopo Peri's Dafne of 1597. In the new genre, a complete story was told through characters, and in addition to choruses and ensembles, the vocal parts included recitative, aria and arioso.[6] Monteverdi's first opera is L'Orfeo which premiered in 1607. The duke was quick to recognise the potential of this new musical form and its potential for bringing prestige to those willing to sponsor it.[7]

Monteverdi wrote the movements of the Vespers piece by piece, while responsible for the ducal services which were held at the Santa Croce chapel at the palace.[8] He completed the large-scale work in 1610. Probably aspiring to a better position, the composition demonstrated his abilities as a composer in any style of his time.[9] The setting was Monteverdi's first published sacred composition after his initial publications nearly thirty years before and stands out for its assimilation of both old and new styles.[10]

Vespers

The liturgical vespers is an evening prayer service according to the Catholic Officium Divinum (Divine Office) of Monteverdi's time, and is in Latin, as were all services of the Catholic Church at the time. Vespers remained structurally unchanged for 1,500 years. The regular prayer service contained five psalms, changing with the liturgical year, the hymn "Ave maris stella", and the Magnificat.[11] The psalms for Marian feasts were the five psalms that Monteverdi set in his work, the first being Psalm 110 in Hebrew counting, but known to Monteverdi as Psalmus 109 in the Vulgate:

| Psalm | Incipit | English |

|---|---|---|

| Psalm 110 | Dixit Dominus | The LORD said unto my Lord |

| Psalm 113 | Laudate pueri | Praise ye [the Lord, O ye] servants of the Lord |

| Psalm 122 | Laetatus sum | I am glad |

| Psalm 127 | Nisi Dominus | Except the Lord [build the house] |

| Psalm 147 | Lauda Jerusalem | Praise, Jerusalem |

The individual psalms and the Magnificat are concluded by the doxology Gloria Patri. Variable elements are antiphons, inserted before each psalm and the Magnificat, which reflect the specific feast and connect the Old Testament psalms to Christian theology.[12] Vespers are traditionally framed by the opening versicle and response from Psalm 70, and the closing blessing.[13]

On ordinary Sundays, vespers were sung in Gregorian chant. On high holidays, such as the feast day of a patron saint, elaborate concertante music was performed. In his Vespers, Monteverdi offered such music without necessarily expecting that all of it would be performed in a given service.[14]

Monteverdi deviated from the typical vespers liturgy by adding motets (concerti), alternating with the psalms. Scholars debate if they were meant to replace antiphons[15] or rather as embellishments of the preceding psalm.[16] He also included a Marian litany, "Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis" (Holy Mary, pray for us).[17] All liturgical texts are set using their psalm tones in Gregorian chant, often as a cantus firmus.[18]

Monteverdi's intentions have been debated among musicologists.[19] Graham Dixon suggests that Monteverdi's setting is more suited for use for the feast of Saint Barbara, claiming, for example, that the texts taken from Song of Songs are applicable to any female saint but that a dedication to fit a Marian feast made the work more "marketable".[20][21]

First publication

The first mention of the publication is in a letter by Monteverdi's assistant, Bassano Casola, to Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga, the duke's younger son, dated July 1610. Casola described the music, mass and vespers, as in the process of being printed, and announced that Monteverdi would travel to Rome to personally dedicate the publication to the pope in the fall.[22] The work was done in Venice, then an important centre for music printing, by Ricciardo Amadino,[22] who had published Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo in 1609. While the opera was published as a score, the vespers music appeared as a set of partbooks.[23] It was published together with a separate composition, a mass called the Missa in illo tempore, which parodied a motet by Nicolas Gombert, "In illo tempore loquante Jesu".[22] The cover describes both works: "Sanctissimae Virgini Missa senis vocibus ad ecclesiarum choros, ac Vespere pluribus decantandae cum nonnullis sacris concentibus ad Sacella sive Principum Cubicula accommodata" (Mass for the Most Holy Virgin for six voices for church choirs, and vespers for several voices with some sacred songs, suitable for chapels and ducal chambers).[22]

One of the partbooks contains the continuo and provides a kind of short score for the more complicated numbers:[23] it gives the title of the Vespers as: "Vespro della Beata Vergine da concerto composta sopra canti firmi" (Vesper for the Blessed Virgin for concertos, composed on cantus firmi).[24] Monteverdi dedicated the work to Pope Paul V who had recently visited Mantua,[25] and dated the dedication 1 September 1610.[26] The schedule seems to have resulted in some of the numbers being printed in haste,[27] and some corrections had to be made. Monteverdi visited Rome as anticipated in October 1610, and appears to have delivered a copy to the pope, at least the music is in the papal library. It is not clear whether he was honoured with a papal audience.[3][28]

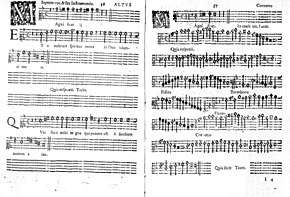

Monteverdi's notation is still in the style of Renaissance music, for example regarding the duration of notes and the absence of bar lines. It poses challenges to editors adopting the current system of notation, which was basically established about a half century after the music was written.[29]

Later publication

After the original print, the next time that parts from the Vespers were published was in an 1834 book by Carl von Winterfeld devoted to the music of Giovanni Gabrieli. He chose the beginning of the Dixit Dominus and of the Deposuit from the Magnificat, discussing the variety of styles in detail. Luigi Torchi published the Sonata as the first complete movement from the Vespers at the turn of the 20th century.[30] The first modern edition of the Vespers appeared in 1932 as part of Gian Francesco Malipiero's edition of Monteverdi's complete works. Two years later, Hans F. Redlich published an edition which dropped two psalms, arranged the other movements in different order, and implemented the figured base in a complicated way. [31] In 1966, Gottfried Wolters edited the first critical edition.[32][33] Critical editions were published, among others, by Clifford Bartlett in 1986,[33] Jerome Roche in 1994,[23] and Uwe Wolf in 2013,[33][34] while Antonio Delfino has edited the Vespers for a complete edition of the composer's works.[33]

Performance

The historical record does not indicate whether Monteverdi actually performed the Vespers in Mantua or in Rome, where he was not offered a post.[9][3] He assumed the position of maestro di cappella at St Mark's Basilica in Venice in 1613, and a performance there seems likely. Church music in Venice is well documented, and performers can draw information for historically informed performances from that knowledge, for example that Monteverdi expected a choir of all male voices.[35]

The Vespers is monumental in scale and requires a choir large and skillful enough to cover up to ten vocal parts, split into separate choirs, and seven soloists. Solo instrumental parts are written for violin and cornett. Antiphons preceding each psalm and the Magnificat, sung in plainchant, would vary with the occasion.[36] Some scholars have argued that the Vespers was not intended as a single work but rather as a collection to choose from.[9]

The edition by Redlich was the basis for performances in Zurich in 1935 and of parts in New York in 1937, among others. It was printed in 1949 and used for the first recording in 1953.[37] The first recording of the work with added antiphons was conducted in 1966 by Jürgen Jürgens.[38] Recent performances have usually aimed to provide the complete music Monteverdi published.[9]

Legacy

Monteverdi's unique approach to each movement of the Vespers earned the composition a place in history.[39] The work not only presents intimate, prayerful moments within its monumental scale, but it also incorporates secular music in this decidedly religious performance, and its individual movements present an array of musical forms – sonata, motet, hymn, and psalm – without losing focus. The musicologist Jeffrey Kurtzman, who edited a publication of the work for Oxford University Press,[40] notes: "... it seems as if Monteverdi were intent in displaying his skills in virtually all contemporary styles of composition, using every modern structural technique".[18] Monteverdi achieves overall unity by building each movement on the traditional Gregorian plainchant for each text, which becomes a cantus firmus in Monteverdi's setting.[10] This "rigorous adhesion to the psalm tones" is similar to the style of Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, who was choirmaster at the Basilica palatina di Santa Barbara at the ducal palace in Mantua.[41]

Music

Structure

Monteverdi's composition is structured in 13 sections.[36][34] The "Ave maris stella" is in seven stanzas set in different scoring, with interspersed ritornelli. The Magnificat is in twelve movements of different scoring, which Monteverdi supplied in two versions.

The table shows the section numbers according to the 2013 edition by Carus,[34] then the function of the section within the vespers, its text source, and the beginning of the text in both Latin and English. The column for the voices has abbreviations SATB for soprano, alto, tenor and bass. A repeated letter means that the voice part is divided, for example TT means "tenor 1 and tenor 2". The column for instruments often contains only their number, because Monteverdi did not always specify the instruments. The basso continuo plays throughout but is listed below (as "continuo") only when it has a role independent of the other instruments or voices. The last column lists the page number of the beginning of the section in the Carus edition.

| No. | Part | Text source | Incipit | English | Voices | Instruments | Page |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Versicle & Response | Psalm 70:1 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende | Make haste, o God, to deliver me | T SSATTB | 6 | 1 |

| 2 | Psalm | Psalm 110 | Dixit Dominus | The LORD said unto my Lord | SSATTB | 6 | 7 |

| 3 | Motet | Song of Songs | Nigra sum | I am black | T | continuo | 18 |

| 4 | Psalm | Psalm 113 | Laudate pueri | Praise, ye servants of the Lord | SSAATTBB | organ | 20 |

| 5 | Motet | Song of Songs | Pulchra es | You are beautiful | 2T | continuo | 36 |

| 6 | Psalm | Psalm 122 | Laetatus sum | I am glad | SSATTB | 38 | |

| 7 | Motet | Isaiah 6:2–3 1 John 5:7 | Duo Seraphim | Two seraphim | 3T | continuo | 49 |

| 8 | Psalm | Psalm 127 | Nisi Dominus | Except the Lord | SATB 2T SATB | 53 | |

| 9 | Motet | Anonymous poem | Audi coelum | Hear my words, Heaven | 2T | continuo | 67 |

| 10 | Psalm | Psalm 147 | Lauda Jerusalem | Praise, Jerusalem | SAB T SAB | 73 | |

| 11 | Sonata | Marian litany | Sancta Maria | Holy Mary | S | 8 | 84 |

| 12 | Hymnus | hymn | Ave maris stella | Hail Star of the Sea | SSAATTBB | 106 | |

| 13 | Magnificat | Luke 2:46–55 Doxology | Magnificat | [My soul] magnifies [the Lord] | SSATTBB | 114 | |

Sections

1 Deus in adjutorium meum intende / Domine ad adjuvandum me festina

The work opens with the traditional versicle and response for vespers, the beginning of Psalm 70 (Psalm 69 in the Vulgate), Deus in adjutorium meum intende (Make haste, O Lord, to deliver me),[42] sung by a solo tenor, with the response from the same verse, Domine ad adjuvandum me festina (Make haste to help me, o Lord),[42] sung by a six-part choir. The movement is accompanied by a six-part orchestra with two cornettos, three trombones (which double the lower strings), strings, and continuo.[43]

| Part | Text source | Incipit | English | Voices | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Versicle | Psalm 70:1 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende | God, come to my assistance | T | 6 |

| Response | Domine ad adjuvandum me festina | Make haste to help me | SSATTB | ||

The music is based on the opening toccata from Monteverdi's 1607 opera L'Orfeo, to which the choir sings a falsobordone recitation on the same chord.[44] The music has been described as "a call to attention" and "a piece whose brilliance is only matched by the audacity of its conception".[45]

2 Dixit Dominus

The first psalm is Psalm 110, beginning Dixit Dominus Dominum meum (The LORD said unto my Lord). Monteverdi set it for a six-part choir with divided sopranos and tenors, and six instruments, prescribing sex vocibus & sex instrumentis. The first tenor begins alone with the cantus firmus. The beginnings of verses are often in falsobordone (a style of recitation), leading to six-part polyphonic settings.[18]

3 Nigra sum

The first motet begins Nigra sum, sed formosa (I am black, but beautiful), taken from the Song of Songs. Monteverdi set it for tenor solo in the new style of monody (a melodic solo line with accompaniment).[46]

4 Laudate pueri

The second psalm is Psalm 113, beginning Laudate pueri Dominum (literally: 'Praise, children, the Lord', in the KJV: 'Praise ye the Lord, O ye servants of the Lord'). Monteverdi wrote eight vocal parts and continuo. The second tenor begins alone with the cantus firmus.[18]

5 Pulchra es

The second motet begins Pulchra es (You are beautiful) from the Song of Songs. Monteverdi set it for two sopranos, who are often in thirds.[46]

6 Laetatus sum

The third psalm is Psalm 122, beginning Laetatus sum (literally: 'I am glad'), a pilgrimage psalm. The music begins with a walking bass, which the first tenor enters with the cantus firmus. The movement is based on four patterns in the bass line and includes complex polyphonic settings and duets.[18]

7 Duo Seraphim

The third motet begins Duo Seraphim (Two angels were calling one to the other), a text combined from Isaiah 6:2–3 and the First Epistle of John, 5:7. Monteverdi set it for three tenors. The first part, talking about the two angels, is a duet. When the text turns to the epistle mentioning the Trinity, the third tenor joins. They sing the text "these three are one" in unison. The vocal lines are highly ornamented.[46]

8 Nisi Dominus

The fourth psalm is Psalm 127, beginning Nisi Dominus (Except the Lord [build] the house). Monteverdi set it for two tenors singing the cantus firmus and two four-part choirs, one echoing the other in overlapped singing.[47]

9 Audi coelum

The fourth motet begins Audi coelum verba mea (Hear my words, Heaven), an anonymous liturgical poem. It is set for two tenors, who sing in call and response (prima ad una voce sola), and expands to six voices when the text reaches the word omnes (all).[48]

10 Lauda Jerusalem

The fifth psalm is Psalm 147, beginning Lauda Jerusalem (Praise, Jerusalem), set for two three-part choirs (SAB) and tenors singing the cantus firmus.[46]

11 Sonata sopra Sancta Maria

The sonata is an instrumental movement with soprano singing of a cantus firmus from the Litany of Loreto (Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis – Holy Mary, pray for us), with rhythmic variants.[49] The movement opens with an instrumental section comparable to a pair of pavane and galliard, with the same material first in even, then in triple metre. The vocal line appears eleven times, while the instruments play uninterrupted virtuoso music reminiscent of vocal parts in the motets.[50]

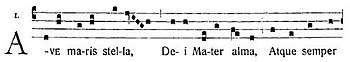

12 Hymnus: Ave maris stella

The penultimate section is devoted to the Marian hymn "Ave maris stella" from the 8th century. Its seven stanzas are set in different scoring. The melody is in the soprano in all verses except verse 6, which is for tenor solo. Verse 1 is a seven-part setting. Verses 2 and 3 are the same vocal four-part setting, verse 2 for choir 1, verse 3 for choir 3. Similarly, verses 4 and 5 are set for soprano, first soprano 1, then soprano 2. Verses 1 to 5 are all followed by the same ritornello for five instruments. Verse 7 is the same choral setting as verse 1, followed by Amen.[51]

| No. | Part | Incipit | English | Voices | Instruments | Page |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12a | Versus 1 | Ave maris stella | Hail Star of the Sea | SSAATTBB | 106 | |

| 12b | Versus 2 | Sumens illud Ave | Receiving that Ave | SATB | 108 | |

| 12c | Ritornello | 5 | 109 | |||

| 12d | Versus 3 | Solve vincla reis | Loosen the chains of the guilty | SATB | 110 | |

| 12e | Ritornello | 5 | ||||

| 12f | Versus 4 | Monstra te esse matrem | Show thyself to be a Mother | S | 111 | |

| 12g | Ritornello | 5 | ||||

| 12h | Versus 5 | Virgo singularis | Unique Virgin | S | ||

| 12i | Ritornello | 5 | ||||

| 12j | Versus 6 | Vita praeasta puram | Bestow a pure life | T | ||

| 12k | Versus 7 | Sit laus Deo Patri Amen | Praise be to God the Father Amen | SSAATTBB | 112 | |

The hymn setting has been regarded as conservative, with the chant melody in the upper voice throughout, but variety is achieved by different numbers of voices and interspersion of a ritornello. The instruments are not specified, to provide further variety. The last stanza repeats the first for formal symmetry.[46]

13 Magnificat

The last movement of a vespers service is the Magnificat. Monteverdi devotes a movement to every verse of the canticle, and two to the doxology. Depending on the mood of the text, the movements are scored for a choir of up to seven voices, in solo, duo or trio singing.[52] Monteverdi uses the initium of the Magnificat tone in every movement, which provides great harmonic variety.[46]

The publication contains a second setting of the Magnificat for six voices and continuo accompaniment.[23]

| No. | Text source | Incipit | Voices | Instruments | Page |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13a | Luke 1:46 | Magnificat | SSATTBB | 6 | 114 |

| 13b | Luke 1:47 | Et exultavit | A T T | 116 | |

| 13c | Luke 1:48 | Quia respexit | T | cornettos, violins, viola da braccio | 118 |

| 13d | Luke 1:49 | Quia fecit | A B B | violins | 122 |

| 13e | Luke 1:50 | Et misericordia | SSATBB | 124 | |

| 13f | Luke 1:51 | Fecit potentiam | A | violins, viola da brazzo | 126 |

| 13g | Luke 1:52 | Deposuit potentes | T | cornettos | 128 |

| 13h | Luke 1:53 | Esurientes implevit bonis | S S | cornettos, violins, viola da brazzo | 130 |

| 13i | Luke 1:54 | Suscepit Israel | S S T | 132 | |

| 13j | Luke 1:55 | Sicut locutus est | A | cornettos, violins | 133 |

| 13k | Doxology | Gloria Patri | S T T | 136 | |

| 13l | Sicut erat in principio | SSATTBB | all instruments | 138 |

Analysis

Monteverdi achieved a collection of great variety both in style and structure, which was unique in his time. Styles range from chordal falsobordone to virtuoso singing, from recitative to polyphonic setting of many voices, and from continuo accompaniment to extensive instrumental obbligato. Structurally, he demonstrated different organisation in all movements.[18]

John Butt, who conducted a recording in 2017 with the Dunedin Consort using one voice per part, summarised the many styles:

"... polychoral textures, virtuoso vocal coloratura, madrigalian vocal polyphony and expressive solo monody and duets, together with some of the most ambitious instrumental music to date. Yet the whole work is suffused with references to the church at its most traditional, with Monteverdi's incessant use of the Gregorian psalm tones for the five extensive psalm settings, the seven-part Magnificat, ... the chant for the Litany, which is integrated within an exuberant instrumental sonata, and the multi-verse setting of the Latin hymn "Ave maris stella".[53]

Butt described the first three psalms as radical in style, while the other two rather follow the polychoral style of Gabrieli, suggesting that the first three may have been composed especially with the publication in mind.[54]

The musicologist Jeffrey Kurtzman observes that the five free concertos (or motets) follow a scheme to first increase then decrease the number of singers, from one to three and back to one, but they increase the number of performers from the first to the last, adding more voices at the end of the fourth and having eight instruments play for the last. In prints by other composers, such concertos appear as a group, usually sorted by number of voices, while Monteverdi interspersed them with the psalms.[50]

In Monteverdi's time, it was common to make adjustments and improvise, depending on the acoustics and the availability and capability of performers. The print of his Vespers shows remarkable detail in reducing this freedom, by precise notation of embellishments and even organ registration, for example.[55]

Recordings

The first recording of the Vespers was arguably an American one made in 1952 with musicians from the University of Illinois conducted by Leopold Stokowski. The recording was released in LP format, probably in 1953,[56] but appears not to have been given normal commercial distribution. The work has since been recorded many times in numerous versions, involving both modern and period instruments. Some recordings allocate the voice parts to choirs, while others use the "one voice per part" concept.[57]

In 1964, John Eliot Gardiner, then a student of history, assembled a group of performers to perform the work in King's College Chapel, Cambridge. This event became the birth of the later Monteverdi Choir.[58] Gardiner recorded the Vespers twice, in 1974 and in 1989.[9]

There is an argument that Monteverdi was offering a compendium of music for vespers from which a selection could be made. For example, normally only one of the two published versions of the Magnificat is performed.[lower-alpha 1] The recordings generally present the music as a unified work, differing in their interpretations of a liturgical context, especially as it involves additional music such as antiphons for a specific feast day.[21] Paul McCreesh, who is well known for his liturgical reconstructions, includes music from other publications and also changes the order of several movements in his 2005 version.[9][59]

See also

- Selva morale e spirituale

Notes

- It is generally assumed that the Magnificat with continuo accompaniment was an alternative for those musical groups lacking the resources to perform the lavishly scored version. Among the recordings of the Vespers, Peter Seymour's is unusual for choosing the Magnificat with continuo.

References

- Constantijn Huygens heard a Vespers by Monteverdi, but on St John's Day; see: Frits Noske An Unknown Work by Monteverdi: The Vespers of St. John the Baptist Music & Letters, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Apr., 1985), pp. 118-122

- Carter 2007.

- Bowers 2010, p. 41.

- Bowers 2010, pp. 41–42.

- Carter 2002, pp. 1–3.

- Ringer 2006, pp. 23–24.

- Ringer 2006, p. 16.

- Bowers 2010, p. 42.

- Kemp 2015.

- Whenham 1997, p. 3.

- Wolf 2013, p. XVI.

- Whenham 1997, p. 9.

- Whenham 1997, pp. 6–8.

- Whenham 1997, p. 10.

- Whenham 1997, pp. 16–17.

- Whenham 1997, p. 21.

- Wolf 2013, p. II.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 3.

- Whenham 1997, p. 6.

- Whenham 1997, pp. 33–34.

- Knighton 1990.

- Wolf 2013, p. XII.

- McCreesh 1995, p. 325.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 1.

- Butt 2017, pp. 8.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 41.

- Wolf 2013, pp. XII, XXVII.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 42.

- Bowers 1992, p. 347.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 15.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 16.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 21.

- Estermann 2015.

- Wolf 2013, pp. 1–141.

- Kurtzman 2000, pp. 6–7.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 2.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 16–17.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 22.

- Kurtzman 1975, pp. 157–158.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 11.

- Whenham 1997, p. 34.

- Wolf 2013, p. XXII.

- Wolf 2013, p. 1.

- Butt 2017, p. 10.

- Whenham 1997, pp. 61–62.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 4.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 3–4.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 4–5.

- Blazey 1989.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 5.

- Wolf 2013, pp. 106–113.

- Wolf 2013, p. 114.

- Butt 2017, pp. 6–7.

- Butt 2017, pp. 8–9.

- Kurtzman 2000, pp. 5–6.

- Kurtzman 2000, p. 516.

- Kurtzman 2000, pp. 516–525.

- Quinn 2016.

- track list

Cited sources

Books

- Carter, Tim (2002). Monteverdi's Musical Theatre. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09676-7.

- Carter, Tim (2007). Monteverdi, Claudio. Grove Music Online. (subscription required)

- Kurtzman, Jeffrey (2000). The Monteverdi Vespers of 1610 – Music, Context, Performance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816409-8.

- Ringer, Mark (2006). Opera's First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi. Newark, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-110-0.

- Whenham, John (1997). Monteverdi: Vespers 1610. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45377-6.

- Wolf, Uwe, ed. (October 2013). Claudio Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine / Marienvesper / Vespers 1610 (PDF). Stuttgart: Carus-Verlag. pp. XII–XX.

Journals

- Blazey, David (May 1989). "A Liturgical Role for Monteverdi's 'Sonata sopra Sancta Maria'". Early Music. 17 (2): 177. JSTOR 3127447.

- Bowers, Roger (August 1992). "Some Reflection upon Notation and Proportion in Monteverdi's Mass and Vespers of 1610". Music & Letters. Oxford University Press. 73 (3): 347–398. doi:10.1093/ml/73.3.347. JSTOR 735294.

- Bowers, Roger (Autumn 2010). "Of 1610: Claudio Monteverdi's 'Mass, motets and vespers'". The Musical Times. 151 (1912): 41–46. JSTOR 25759499.

- Kemp, Lindsay (9 February 2015). "Monteverdi's Vespers – which recording is best?". Gramophone. London.

- Knighton, Tess (February 1990). "Monteverdi Vespers". Gramophone. London.

- Kurtzman, Jeffrey (1975). Some Historical Perspectives on the Monteverdi Vespers (PDF). Rice University Studies. pp. 123–182.

- McCreesh, Paul (May 1995). "Monteverdi Vespers: Three New Editions". Early Music. 23 (2): 325–327. JSTOR 3137712.

Online sources

- Butt, John (2017). Monteverdi / Vespers 1610 / Dunedin Consort (PDF) (Media notes). Dunedin Consort. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Estermann, Josef (22 April 2015). "Monteverdi variabel". musikzeitung.ch (in German). Schweizer Musikzeitung. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Quinn, John (May 2016). "Review recording of the month / Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) / Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

Further reading

- Stevens, Denis (July 1961). "Where Are the Vespers of Yesteryear?". The Musical Quarterly. 47 (3): 315–330.

- Bonta, Stephen (Spring 1967). "Liturgical Problems in Monteverdi's Marian Vespers". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 20 (1): 87–106.

- Parrott, Andrew (November 1984). "Transposition in Monteverdi's Vespers of 1610 / An 'Aberration' Defended". Early Music. 12 (4): 490–516.

- Kurtzman, Jeffrey (February 1985). "An Aberration Amplified". Early Music. 13 (1): 73+75-76.

- Parrott, Andrew (October 1995). "Getting It Right". The Musical Times. 136 (1832): 531–535.

- Parrott, Andrew (May 2004). "Onwards and Downwards". Early Music. 32 (2): 303–317.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vespro della Beata Vergine. |

- Sanctissimae Virgini Missa senis vocibus ac Vesperae pluribus decantandae (Monteverdi, Claudio): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Vespro della Beata Vergine: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Vespro della Beata Vergine: Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Literature about Vespro della Beata Vergine in the German National Library catalogue

- Video of a performance of the "Nigra Sum" from the Vespers on original instruments in meantone tuning by the ensemble Voices of Music using baroque vocal ornamentation, instruments and playing techniques

- Andrew Clements: Monteverdi: Vespers of 1610 / CD review – authentic but incoherent The Guardian, 19 January 2017

- John Kilpatrick: Monteverdi Vespers of 1610: John Kilpatrick's Edition, for 2010