Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban, later Marquis de Vauban[1] (1 May 1633 – 30 March 1707) commonly referred to as Vauban (French: [vobɑ̃]), was a French military engineer, who participated in each of the wars fought by France during the reign of Louis XIV.

Sébastien le Prestre, Marquis de Vauban | |

|---|---|

Sébastien le Prestre, Marquis de Vauban | |

| Born | 4 May 1633 Saint-Léger-Vauban, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté |

| Died | 30 March 1707 (aged 73) Paris |

| Buried | Bazoches, later reburied in Les Invalides |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Engineer |

| Years of service | 1651–1703 |

| Rank | Maréchal de France 1703 |

| Commands held | Commissaire général des fortifications (1678–1703) |

| Battles/wars | Franco-Spanish War 1635–1659 War of Devolution 1667–1668 Franco-Dutch War 1672–1678 War of the Reunions 1683–1684 Nine Years' War 1688–1697 War of the Spanish Succession 1701–1714 |

| Awards | Order of the Holy Spirit Order of Saint Louis May 1693 Honorary Member French Academy of Sciences |

Considered the expert in his field, rivaled only by his Dutch contemporary Menno van Coehoorn, Vauban's design principles served as the dominant model of fortification for nearly 100 years. His offensive tactics were used until the early twentieth century. He made a number of innovations in the use of siege artillery and founded the Corps royal des ingénieurs militaires, the basis of combat engineering units in the French military.

He worked on improving many of France's major ports and harbours, as well as civilian infrastructure projects such as the Canal de la Bruche. In addition to publications on engineering design, strategy and training, shortly before his death in 1707 he produced an economic tract entitled La Dîme royale. This was later destroyed by Royal decree. It contained radical proposals for a more even distribution of the tax burden; his use of statistics to support his arguments makes the paper a precursor of modern economics. His application of rational and scientific methods to problem-solving, whether engineering or social, anticipated an approach that became common in the Age of Enlightenment.

Finally, one of the most significant and enduring aspects of Vauban's legacy was his view of France as a geographical and economic entity. Unusually for the time, Vauban advocated destroying fortifications and giving up territory as part of establishing a more coherent and defensible border. The boundaries established in the north and east as a result have changed very little in the four centuries since.[2]

Life

Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban was born 4 May 1633, in Saint-Léger-de-Foucheret, in the Nièvre, now part of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. His birthplace was renamed Saint-Léger-Vauban by Napoleon III in 1867.[3]

His parents, Urbain le Prestre (ca 1602-1652) and Edmée de Comignolle (?-ca 1651), were members of the minor nobility, from Vauban in Bazoches. His grandfather Jacques acquired Château de Bazoches in 1570 when he married Françoise de la Perrière, an illegitimate daughter of the Comte de Bazouches, who died intestate. The resulting 30 year legal battle by the Le Pestre family to retain the property proved financially ruinous.

Urbain became a forestry-worker, which he combined with the design and maintenance of gardens for the local gentry. This included the Château de Ruère, owned by the Huguenot De Bricquemaut family, where Vauban spent his early years.[4]

In 1660, Vauban married Jeanne d'Aunay d'Epiry (ca 1640-1705); they had two daughters, Charlotte (1661-1709) and Jeanne Françoise (1678-1713), as well as a short-lived infant son.[5] He also had a long-term relationship with Marie-Antoinette de Puy-Montbrun, daughter of an exiled Huguenot officer, referred to as la Belle Mademoiselle de Villefranche.[6]

His only sister Charlotte (1638-1645?) died young but he had a large number of relatives; his cousin Paul le Prestre (ca 1630-1703) was an army officer, who supervised construction of Les Invalides.[7] Three of Paul's sons served in the army, two of whom were killed in action in 1676 and 1677. The third, Antoine (1654-1731), became Vauban's assistant and later a Lieutenant-General; in 1710, he was appointed Governor of Béthune for life, while he inherited Vauban's titles and the bulk of his lands.[8]

Vauban died in Paris on 30 March 1707 and was buried near his home in Bazoches. The grave was destroyed during the French Revolution and in 1808, Napoléon Bonaparte ordered his heart reburied in Les Invalides, resting place for many of France's most famous soldiers.[9]

Career

The first half of the 17th century in France was one of intense civil and military strife. The religious wars that ended in 1598 restarted in the 1620s, French support for the Dutch Republic led to the 1635–1659 Franco-Spanish War, then followed by a 1648-1653 civil war known as the Fronde. Like many others, Vauban was impacted by these events; although the Le Prestre family was Catholic, his grandfather served Huguenot leader Admiral Coligny, and his first wife was a Protestant from La Rochelle, while two of his uncles died in the war with Spain.[10]

At the age of ten, Vauban was sent to the Carmelite college in Semur-en-Auxois, where he was taught the basics of mathematics, science and geometry. His father's work was also relevant, since neo-classical garden design and the layout of fortifications were closely linked.[11] Many worked on both, including Marlborough's military engineer John Armstrong (1674–1742), who designed the lake and gardens at Blenheim Palace.[12]

In 1650, Vauban joined the household of his local magnate, Condé, where he met Charles, Comte de Montal, a close neighbour from Nièvre. Colleagues for many years, Louis XIV reportedly remarked sieges should ideally be conducted by Vauban and defended by de Montal, but could only happen once, since they would kill each other.[13]

During the 1650–1653 Fronde des nobles, Condé was arrested by the Regency Council, led by Louis XIV's mother Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin. After being released in 1652, he and many of his followers went into exile in the Spanish Netherlands and allied with the Spanish.[14]

One of Condé's possessions included Sainte-Menehould, and in 1652, Vauban helped construct its defences.[15] He changed sides after being captured by a Royalist patrol in early 1653, serving in the force led by Louis Nicolas de Clerville that took Sainte-Meenhould in November. Clerville, later appointed Commissaire general des fortifications, employed him on siege operations, and building fortifications. He was appointed Ingénieur du Roi or Royal Engineer in 1655, and by the time the war ended in 1659, he was known as a talented engineer of energy and courage.[16]

Under the terms of the Treaty of the Pyrenees, Spain ceded much of French Flanders and Vauban was put in charge of fortifying newly-acquired towns such as Dunkirk. This pattern of French territorial gains, followed by fortification of new strongpoints was followed in the subsequent 1667–1668 War of Devolution, 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War and 1683-1684 War of the Reunions. In the course of his career, Vauban supervised or designed the fortification of over 300 locations, [lower-alpha 1] and by his own estimate conducted over 40 sieges, starting with Sainte-Menehould in 1653 and ending at Ath in 1697.[17]

The Siege of Maastricht in 1673 was the first time Vauban directed siege operations, rather than providing technical advice, although the role had no military rank and he was subordinate to the senior officer present.[18] This meant Louis took credit for its capture but Vauban was rewarded with a large sum of money, which he used to purchase the Château de Bazouches from his cousin in 1675.[19]

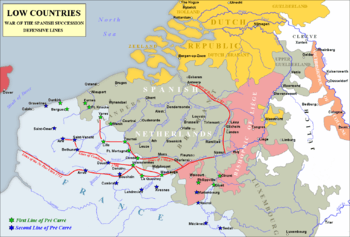

Post-1673, French strategy in Flanders was largely based on a memorandum from Vauban to Louvois, Minister of War, setting out a proposed line of fortresses known as the Ceinture de fer or iron belt (see map).[20] One suggestion for Vauban's increased prominence was the death of Turenne in 1675, followed by Condé's retirement; both were aggressive commanders and arguably the most talented French generals of the 17th century.[21]

He was made Maréchal de camp in 1676 and Commissaire general des fortifications after Clerville died in 1677 but the 1678 Treaty of Nijmegen was the highpoint of French expansion under Louis XIV, while Louvois' death in 1691 deprived Vauban of much of his influence at Court.[20] Nevertheless, he supervised the capture of Namur in 1692, the major French achievement of the Nine Years' War in the Spanish Netherlands and that of Ath in 1697, often considered his offensive masterpiece.[22]

In addition to substantial financial rewards, Vauban became Comte de Vauban, a member of the Order of the Holy Spirit and Order of Saint Louis, and an Honorary Member of the French Academy of Sciences.[23] However, the demands of siege warfare meant armies of the Nine Years' War often exceeded 100,000 men, a size unsustainable for the pre-industrial economies of its participants.[24] The War of the Spanish Succession saw a much greater emphasis on mobile warfare; Vauban was promoted Maréchal de France in 1703 and held his first military command at the siege of Alt-Breisach but this was the end of his active career. His advice was now ignored; asked his opinion of French strategy at the Siege of Turin in 1706, he responded success was so unlikely, he would have his throat cut if Turin fell using this approach, an assessment that proved correct.[25]

The Ceinture de fer proved its worth after the French defeat at Ramillies in 1706; under pressure from superior forces on multiple fronts, France's northern border remained largely intact despite repeated efforts to break it. The capture of Lille alone cost the Allies 12,000 casualties and most of the 1708 campaigning season; the lack of progress between 1706–1712 enabled Louis to reach an acceptable deal at Utrecht in 1713, as opposed to the humiliating terms presented in 1707.[26]

As he grew older, Vauban took an increasingly broad view of his role; his fortifications were designed for mutual support, so he built or planned infrastructure, including roads, bridges and canals. They required supplies, so he prepared maps showing location and quantity of resources eg forges, forests, farms etc, even instructions on how to breed pigs. This inevitably led onto taxation; by 1705, the French economy was exhausted, a combination of the cost of Louis' wars and the impact of the Little Ice Age, a period of colder and wetter weather during the second half of the 17th century that drastically reduced crop yields.[27] The Great Famine of 1695-1697 killed between 15-25% of the population in present-day Scotland, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Norway and Sweden, with an estimated two million deaths in France and Northern Italy.[28]

Shortly before his death in 1707, he published La Dîme royale, which documented the economic misery of the lower classes. His upbringing made him unusually sympathetic to the impact of war on the poor; on one occasion, he requested compensation be paid a man with eight children whose land was taken to build one of his forts.[29] However, it should also be noted his siege works required the conscription of large numbers of unpaid workers, with severe punishments for those who tried to evade service; 20,000 at Maastricht in 1673 and Mons in 1691, 12,000 at Charleroi in 1693.[30]

Vauban's solution was to levy a flat 10% tax on all agricultural and industrial output, while eliminating tax exemptions, which meant the vast majority of the nobility and clergy paid no taxes. Although confiscated and destroyed by Royal decree, the use of statistics to support his arguments ... establishes Vauban as a founder of modern economics and a precursor of the Enlightenment's socially concerned intellectuals.[31]

Doctrines and legacy

Offensive doctrines; siege warfare

While his modern fame rests on the fortifications he built, Vauban's greatest innovations were in the field of offensive operations, an approach he summarised as 'More powder, less blood.' Initially reliant on existing concepts, he later adapted them, which he set out in a memorandum of March 1672 entitled Mémoire pour servir à l'instruction dans la conduite des sièges.[32]

In this period, sieges became the dominant form of warfare; during the 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War, three battles were fought in the Spanish Netherlands, of which only Seneffe was unrelated to a siege. Their importance was heightened by Louis XIV, who viewed them as low-risk opportunities for demonstrating his military skill and increasing his prestige; he was present at 20 of those conducted by Vauban.[29]

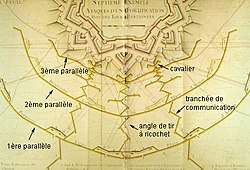

The 'siege parallel' had been in development since the mid-16th century but Vauban brought the idea to practical fulfilment at Maastricht in 1673.[33] Three parallel trenches were dug in front of the walls, the earth thus excavated being used to create embankments screening the attackers from defensive fire, while bringing them as close to the assault point as possible (see Diagram). Artillery was moved into the trenches, allowing them to target the base of the walls at close range, with the defenders unable to depress their own guns enough to counter this; once a breach had been made, it was then stormed. This approach was used in offensive operations well into the 20th century.[34]

However, Vauban emphasised flexibility; after its debut at Maastricht, he did not use the siege parallel again until Valenciennes in 1677. His willingness to challenge accepted norms was further demonstrated when he proposed storming the breach in daylight, rather than at night. He argued this would reduce casualties by surprising the defenders and allow better co-ordination among the assault force; this was opposed by Marshall Luxembourg but approved by Louis and the attack proved successful.[35]

In addition, an often overlooked feature of French tactics in this period was weakening towns in advance by severely restricting supplies. During the winter of 1676/1677, the French imposed a tight blockade on Cambrai, Valenciennes and Saint-Omer; Spanish officers had to disguise themselves as peasants to evade it and one French commander was reprimanded for allowing a Spanish official to slip into Cambrai in late January.[36]

Vauban made several important innovations in the use of siege artillery, including ricochet firing and concentrating fire on specific parts of the fortifications, rather than the previous practice of targeting multiple targets. The same principle was employed by his Dutch rival Menno van Coehoorn; the 'Van Coehoorn method' sought to overwhelm defences with massive firepower, such as the Grand Battery of 200 guns at Namur in 1695, while Vauban preferred a more gradual approach.[37] Both had their supporters; Vauban argued his was more efficient and less costly in terms of casualties but it took more time, an important consideration in an age when far more soldiers died from disease than in combat.[38]

Defensive doctrines; fortifications

Military engineers and generals accepted that given time, even the strongest fortifications would fall; the process was so well understood by the 1690s that betting on the length of a siege became a popular craze.[39] As few states could afford large standing armies, defenders needed time to mobilise; to provide this, fortresses were designed to absorb the attackers' energies, similar to the use of crumple zones in modern cars.[40] The French defence of Namur in 1695 showed "how one could effectively win a campaign, by losing a fortress but exhausting the besiegers."[41]

As with the siege parallel, the strength of Vauban's defensive designs was his ability to synthesise and adapt the work of others to create a more powerful whole; throughout his career, he used the famous 'star-shape' bastion fort design or trace Italienne, based largely on the work of Antoine de Ville (1596–1656) and Blaise Pagan (1603–1665).[42] Subsequent adaptations, or 'systems', strengthened their internal works with the addition of casemated shoulders and flanks.[29]

The principles of his 'second system' were set out in the 1683 work Le Directeur-Général des fortifications, and used at Landau and Mont-Royal, near Traben-Trarbach; both were advanced positions, intended as stepping-off points for French offensives into the Rhineland.[43] Located 200 metres above the Moselle, Mont-Royal had main walls 30 metres high, three kilometres long and space for 12,000 troops; this enormously expensive work was demolished when the French withdrew after the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick and only the foundations remain today.[44] Fort-Louis was another new construction, built on an island in the middle of the Rhine; this allowed Vauban to combine his defensive principles with town planning, although like Mont-Royal, little of it remains.[45]

The French retreat from the Rhine after 1697 required new fortresses; Neuf-Brisach was the most significant, designed on Vauban's 'third system' and completed after his death by Louis de Cormontaigne. Using ideas from Fort-Louis, this incorporated a regular square grid street pattern inside an octagonal fortification; tenement blocks were built inside each curtain wall, strengthening the defensive walls and shielding more expensive houses from cannon fire.[46]

Vauban considered not only construction of fortifications, but advocated destroying poor fortifications and giving up poorly defensible territory to establish a more coherent border. In December 1672 he wrote to his patron at court, Louvois: "I am not for the greater number of places, we already have too many, and please God that we had half of that but all in good condition!" [47]

Infrastructure; harbours, canals and town planning

Infrastructure projects are a less acknowledged feature of Vauban's legacy and he worked on many of France's major ports, including Brest, Dunkerque and Toulon. His fortifications were designed for mutual support, making roads and waterways an essential part of their design, such as the Canal de la Bruche, a 20-kilometre (12 mi) canal built in 1682 to transport materials for the fortification of Strasbourg.[11] He also provided advice and direction on the repair and enlargement of the Canal du Midi in 1686.[48]

His holistic approach to urban planning, which integrated defences with the city layout and infrastructure is most obvious at Neuf-Brisach. This element of his legacy is recognised in the Vauban district in Freiburg, developed as a model for sustainable neighbourhoods post-1998.[49]

Vauban's 'scientific approach' and focus on large infrastructure projects strongly influenced American military and civil engineering and inspired the creation of the US Corps of Engineers in 1824.[50] Until 1866, West Point's curriculum was modelled on that of the Ecole Polytechnique and as in France, was designed to produce officers with skills in engineering and mathematics.[51]

Training engineers

During the second half of the 17th century, the military became increasingly professional and one of Vauban's chief concerns was the shortage of skilled engineers. One way to manage this was reducing casualties, another increasing supply and in 1690, he established the Corps royal des ingénieurs militaires. This school was the origin of modern French combat engineering units and until his death, potential candidates had to pass an examination administered by Vauban himself.[52] Many of his publications, including Traité de l'attaque des places, a summary of the fully developed Vauban attack, and Traité des mines on military mining were written at the end of his career in order to provide a training curriculum for his successors.[53]

Assessment

Vauban's offensive tactics remained relevant for centuries; many of his principles were used by the Việt Minh at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.[30] His defensive fortifications dated far more quickly, one reason being the enormous investment required to first build, then defend them; Vauban himself estimated that in 1678, 1694 and 1705, between 40 and 45% of the French army was assigned to garrison duty.[54] As early as 1701, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, argued winning one battle was more beneficial than taking 12 fortresses, an argument supported by Van Coehoorn.[55]

Vauban's reputation was such that even after developments in artillery made them obsolete, his designs remained in use decades later, such as Bourtange, built in the Netherlands in 1742. His prominence was also driven by his emphasis on scientific method, a common theme of the Age of Enlightenment, which held every activity could be expressed in terms of a universal system, including tactics.[56] The Corps des ingénieurs militaires was based on his teachings; between 1699 and 1743, only 631 new candidates were accepted, the vast majority relatives of existing or former members.[57]

As a result, French military engineering became ultra-conservative, while many 'new' works used his designs, or professed to do so, such as those built by Louis de Cortmontaigne at Metz in 1728–1733. This persisted into the late 19th century; Fort de Queuleu, built in 1867 near Metz, was a Vauban-style strongpoint, despite being obsolete decades previously.[58]

Ironically, a small minority of French engineers continued to be innovators in the field, most notably the Marquis de Montalembert, who in 1776 began publication of La Fortification perpendiculaire. A rejection of the principles advocated by Vauban and his successors, his ideas were dismissed in France but became prevailing orthodoxy in much of Europe.[59]

Notes

- Including Antibes (Fort Carré), Arras, Auxonne, Barraux, Bayonne, Belfort, Bergues, Citadel of Besançon, Bitche, Blaye, Briançon, Bouillon, Calais, Cambrai, Colmars-les-Alpes, Collioure, Douai, Entrevaux, Givet, Gravelines, Hendaye, Huningue, Joux, Kehl, Landau, Le Palais (Belle-Île), La Rochelle, Le Quesnoy, Lille, Lusignan, Le Perthus (Fort de Bellegarde), Luxembourg, Maastricht, Maubeuge, Metz, Mont-Dauphin, Mont-Louis, Montmédy, Namur, Neuf-Brisach, Perpignan, Plouezoc'h (in French) (Château du Taureau) (in French), Rocroi, Saarlouis, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, Saint-Omer, Sedan, Strasbourg, Toul, Valenciennes, Verdun, Villefranche-de-Conflent (town and Fort Liberia), and Ypres. He directed the building of 37 new fortresses, and fortified military harbours, including Ambleteuse, Brest, Dunkerque, Freiburg im Breisgau, Lille (Citadel of Lille), Rochefort, Saint-Jean-de-Luz (Fort Socoa), Saint-Martin-de-Ré, Toulon, Wimereux, Le Portel, and Cézembre

References

- Sébastien Le Prestre Vauban (marquis de, 1633-1707), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 30 April 2019.

- Langins 2003, p. 11.

- "Vauban 1633-1707". Histoire pour Tous (in French). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Pujo 1991, p. 112.

- Homs, George J. "Sébastien Le Prestre, marquis de Vauban". Geni.com. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "F Marie-Antoinette du PUY-MONTBRUN la Belle Mademoiselle de Villefranche". Geneanet. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- LePage 2009, p. 17.

- Desvoyes 1872, p. 13.

- "Dome des Invalides". Musée de l'Armée Invalides. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Pujo 1991.

- Wolfe 2009, p. 151.

- Latcham, 2004 & ONDB Online.

- Moreri 1749, p. 690.

- Tucker 2009, p. 654.

- Duffy 1995, p. 136.

- LePage 2009, p. 9.

- LePage 2009, pp. 57-58.

- LePage 2009, p. 57.

- "Château de Bazoches". Chemins de Mémoires. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Wolfe 2009, p. 149.

- Starkey 2003, p. 38.

- Ostwald 2006, p. 47.

- Leridon 2004, p. 85.

- Childs 1991, p. 2.

- Lynn 1999, p. 309.

- Kamen 2001, pp. 70–72.

- White, Lynch 2011, pp. 542–543.

- de Vries 2009, pp. 151–194.

- Holmes, 1991 & ONDB Online.

- LePage 2009, p. 56.

- France, Dejean, 2005 & Vauban, Sébastien le Prestre, seigneur de.

- LePage 2009, p. 43.

- Duffy 1995, p. 10.

- Vesilind 2010, p. 23.

- De Périni 1896, p. 186.

- Satterfield, pp. 304–305.

- Ostwald 2006, pp. 285-286.

- Afflerbach, Strachan 2012, pp. 159-160.

- Manning 2006, pp. 413–414.

- Afflerbach, Strachan 2012, p. 159.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 248–249.

- LePage 2009, pp. 69-72.

- Duffy 1995, p. 20.

- "Fortress Mont Royal". Traben-Tarbach Tourist Information. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Fort Louis". The Fortifications of Vauban. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Dobroslav 1992, p. 221.

- LePage 2009, p. 142.

- Allende 1805, pp. 688–691.

- Schiller 2010.

- Klosky 2013, pp. 69–87.

- Baldwin, James. "Engineering, military". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Mousnier 1979, pp. 577–578].

- Ostwald 2006, pp. 123–124.

- Lynn 1997, p. 62.

- Van Hoof 2004, p. 83.

- Gay 1996.

- Mousnier 1979, pp. 577–578.

- LePage 2009, pp. 283-284.

- Delon, Picon 2001, pp. 540–451.

Sources and bibliography

- Lt-Colonel Allende, A (1805). Histoire du Corps impérial du génie: Volume 1. Magimel, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume V. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Desvoyes, Léon-Paul (1872). "Genealogie de la famille Le Prestre de Vauban". Bulletin de la Société des Sciences Historiques et Naturelles de Semur.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Antoine, Picon (2001). Delon, Michel (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Routledge. ISBN 978-1579582463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- de Vries, Jan (2009). "The Economic Crisis of the 17th Century". Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 40 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Dobroslav, Libal (1992). An Illustrated History of Castles. Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0600573104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Duffy, Christopher (1995). Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415146494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Joan, Dejean (2005). France, Peter (ed.). The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French. OUP. ISBN 9780191735004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Gay, Peter (1996). The Enlightenment: An Interpretation. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393008708.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Griffith, Paddy, Dennis, Peter (2006). The Vauban fortifications of France. Osprey.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Halévy, Daniel (1924). Vauban. Builder of Fortresses. Geoffrey Bles.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Hebbert, F.J. (1990). Soldier of France: Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban, 1633–1707. P. Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-0890-3.;

- Holmes, Richard (2001). Vauban, Marshal Sebastien le Prestre de (1633–1707). doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606963.001.0001. ISBN 9780198606963.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Kamen, Henry (2001). Philip V of Spain: The King Who Reigned Twice. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300180541.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Klosky, J. Ledlie, Klosky, Wynn E. (2013). "Men of action: French influence and the founding of American civil and military engineering". Construction History. 28 (3). JSTOR 43856053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Langins, Jānis (2004). Conserving the enlightenment: French military engineering from Vauban to the revolution. MIT Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Leridon, Henri (2004). "The Demography of a Learned Society: the Académie des Sciences (Institut de France), 1666-2030". Population. 59 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Lynn, John (1997). Giant of the Grand Siècle: The French Army, 1610-1715 (2008 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521032483.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Manning, Roger (2006). An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585-1702. OUP. ISBN 978-0199261499.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Moreri, Louis (1749). Le grand dictionnaire historique ou Le melange curieux de l'Histoire sacrée; Volume I. Libraires Associes, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Mousnier, Roland (1979). The Institutions of France Under the Absolute Monarchy, 1598-1789. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226543277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Ostwald, Jamel (2006). Vauban Under Siege: Engineering Efficiency and Martial Vigor in the War of the Spanish Succession. Brill. ISBN 978-9004154896.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Pujo, Bernard (1991). Vauban. Albin Michel. ISBN 978-2226052506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Satterfield, George (2003). Princes, Posts and Partisans: The Army of Louis XIV and Partisan Warfare in the Netherlands (1673-1678). Brill. ISBN 978-9004131767.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Schiller, Preston (2010). An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and. Routledge. ISBN 978-1844076659.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Starkey, Armstrong (2003). War in the Age of Enlightenment, 1700-1789. Praeger. ISBN 978-0275972400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Tellier, Luc-Normand (1987). Face aux Colbert : les Le Tellier, Vauban, Turgot ... et l'avènement du libéralisme. Presses de l'Université du Québec.;Etext;

- Tucker, Spencer C (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East 6V: A Global Chronology of Conflict [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096671.;

- Van Hoof, Jaep (2004). Menno van Coehoorn 1641–1704, Vestingbouwer – belegeraar – infanterist. Instituut voor Militaire Geschiedenis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vesilind, P Aame (2010). Engineering Peace and Justice: The Responsibility of Engineers to Society. Springer. ISBN 978-1447158226.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- White, I.D. (2011). Lynch, Michael (ed.). Rural Settlement 1500–1700 in The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. OUP. ISBN 978-0199693054.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolfe, Michael (2009). Walled Towns and the Shaping of France: From the Medieval to the Early Modern Era. AIAAA. ISBN 978-0230608122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

External links

- "Château de Bazoches". Chemins de Mémoires. Retrieved 5 January 2019.;

- "Dome des Invalides". Musée de l'Armée Invalides. Retrieved 6 January 2019.;

- "Fortress Mont Royal". Traben-Tarbach Tourist Information.;

- Marshal Vauban Homepage at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009) (much detail)

- (in French) Details about many works by Vauban at cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr

- (in French) 40 citadels of Vauban, aerial views by Franck Lechenet

- (in French) aerial pictures of the 100 citadels in France, wonderful shots

- Baldwin, James. "Engineering, military". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.

| French nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by first creation |

Comte de Vauban 1693–1707 |

Succeeded by Antoine le Prestre 1707-1754 |