Trusted Platform Module

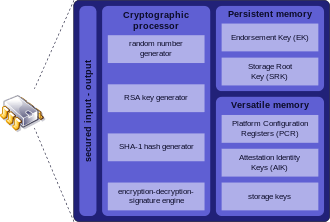

Trusted Platform Module (TPM, also known as ISO/IEC 11889) is an international standard for a secure cryptoprocessor, a dedicated microcontroller designed to secure hardware through integrated cryptographic keys.

History

Trusted Platform Module (TPM) was conceived by a computer industry consortium called Trusted Computing Group (TCG), and was standardized by International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in 2009 as ISO/IEC 11889.[1]

TCG continued to revise the TPM specifications. The last revised edition of TPM Main Specification Version 1.2 was published on March 3, 2011. It consisted of three parts, based on their purpose.[2] For the second major version of TPM, however, TCG released TPM Library Specification 2.0, which builds upon the previously published TPM Main Specification. Its latest edition was released on September 29, 2016, with several errata with the latest one being dated on January 8, 2018.[3][4]

Overview

Trusted Platform Module provides

- A random number generator[5][6]

- Facilities for the secure generation of cryptographic keys for limited uses.

- Remote attestation: Creates a nearly unforgeable hash key summary of the hardware and software configuration. The software in charge of hashing the configuration data determines the extent of the summary. This allows a third party to verify that the software has not been changed.

- Binding: Encrypts data using the TPM bind key, a unique RSA key descended from a storage key.[7]

- Sealing: Similar to binding, but in addition, specifies the TPM state for the data to be decrypted (unsealed).[8]

Computer programs can use a TPM to authenticate hardware devices, since each TPM chip has a unique and secret RSA key burned in as it is produced. Pushing the security down to the hardware level provides more protection than a software-only solution.[9]

Uses

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) specifies that "new computer assets (e.g., server, desktop, laptop, thin client, tablet, smartphone, personal digital assistant, mobile phone) procured to support DoD will include a TPM version 1.2 or higher where required by DISA STIGs and where such technology is available." DoD anticipates that TPM is to be used for device identification, authentication, encryption, and device integrity verification.[10]

Platform integrity

The primary scope of TPM is to assure the integrity of a platform. In this context, "integrity" means "behave as intended", and a "platform" is any computer device regardless of its operating system. It is to ensure that the boot process starts from a trusted combination of hardware and software, and continues until the operating system has fully booted and applications are running.

The responsibility of assuring said integrity using TPM is with the firmware and the operating system. For example, Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) can use TPM to form a root of trust: The TPM contains several Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs) that allow secure storage and reporting of security relevant metrics. These metrics can be used to detect changes to previous configurations and decide how to proceed. Good examples can be found in Linux Unified Key Setup (LUKS),[11] BitLocker and PrivateCore vCage memory encryption. (See below.)

An example of TPM use for platform integrity is the Trusted Execution Technology (TXT), which creates a chain of trust. It could remotely attest that a computer is using the specified hardware and software.[12]

Disk encryption

Full disk encryption utilities, such as dm-crypt and BitLocker, can use this technology to protect the keys used to encrypt the computer's storage devices and provide integrity authentication for a trusted boot pathway that includes firmware and boot sector.

Password protection

Operating systems often require authentication (involving a password or other means) to protect keys, data or systems. If the authentication mechanism is implemented in software only, the access is prone to dictionary attacks. Since TPM is implemented in a dedicated hardware module, a dictionary attack prevention mechanism was built in, which effectively protects against guessing or automated dictionary attacks, while still allowing the user a sufficient and reasonable number of tries. Without this level of protection, only passwords with high complexity would provide sufficient protection.

Other uses and concerns

Any application can use a TPM chip for:

- Digital rights management

- Protection and enforcement of software licenses

- Prevention of cheating in online games[13]

Other uses exist, some of which give rise to privacy concerns. The "physical presence" feature of TPM addresses some of these concerns by requiring BIOS-level confirmation for operations such as activating, deactivating, clearing or changing ownership of TPM by someone who is physically present at the console of the machine.[14][15]

TPM implementations

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Repository | github |

| Written in | C, C++ |

| Type | TPM implementation |

| License | BSD License |

| Website | trustedcomputinggroup |

Starting in 2006, many new laptops have been sold with a built-in TPM chip. In the future, this concept could be co-located on an existing motherboard chip in computers, or any other device where the TPM facilities could be employed, such as a cellphone. On a PC, either the LPC bus or the SPI bus is used to connect to the TPM chip.

The Trusted Computing Group (TCG) has certified TPM chips manufactured by Infineon Technologies, Nuvoton, and STMicroelectronics,[16] having assigned TPM vendor IDs to Advanced Micro Devices, Atmel, Broadcom, IBM, Infineon, Intel, Lenovo, National Semiconductor, Nationz Technologies, Nuvoton, Qualcomm, Rockchip, Standard Microsystems Corporation, STMicroelectronics, Samsung, Sinosun, Texas Instruments, and Winbond.[17]

There are five different types of TPM 2.0 implementations:[18][19]

- Discrete TPMs are dedicated chips that implement TPM functionality in their own tamper resistant semiconductor package. They are theoretically the most secure type of TPM because the routines implemented in hardware should be more resistant to bugs versus routines implemented in software, and their packages are required to implement some tamper resistance.

- Integrated TPMs are part of another chip. While they use hardware that resists software bugs, they are not required to implement tamper resistance. Intel has integrated TPMs in some of its chipsets.

- Firmware TPMs are software-only solutions that run in a CPU's trusted execution environment. Since these TPMs are entirely software solutions that run in trusted execution environments, these TPMs are more likely to be vulnerable to software bugs. AMD, Intel and Qualcomm have implemented firmware TPMs.

- Software TPMs are software emulators of TPMs that run with no more protection than a regular program gets within an operating system. They depend entirely on the environment that they run in, so they provide no more security than what can be provided by the normal execution environment, and they are vulnerable to their own software bugs and attacks that are penetrating the normal execution environment. They are useful for development purposes.

- Virtual TPMs are provided by a hypervisor. Therefore, they rely on the hypervisor to provide them with an isolated execution environment that is hidden from the software running inside virtual machines to secure their code from the software in the virtual machines. They can provide a security level comparable to a firmware TPM.

The official TCG reference implementation of the TPM 2.0 Specification has been developed by Microsoft. It is licensed under BSD License and the source code is available on GitHub.[20] Microsoft provides a Visual Studio solution and Linux autotools build scripts.

In 2018, Intel open-sourced its Trusted Platform Module 2.0 (TPM2) software stack with support for Linux and Microsoft Windows.[21] The source code is hosted on GitHub and licensed under BSD License.[22][23]

Infineon funded the development of an open source TPM middleware that complies with the Software Stack (TSS) Enhanced System API (ESAPI) specification of the TCG.[24] It was developed by Fraunhofer Institute for Secure Information Technology (SIT).[25]

IBM's Software TPM 2.0 is an implementation of the TCG TPM 2.0 specification. It is based on the TPM specification Parts 3 and 4 and source code donated by Microsoft. It contains additional files to complete the implementation. The source code is hosted on SourceForge and licensed under BSD License.[26]

TPM 1.2 vs TPM 2.0

While TPM 2.0 addresses many of the same use cases and has similar features, the details are different. TPM 2.0 is not backward compatible to TPM 1.2.[27]

| Specification | TPM 1.2 | TPM 2.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | The one-size-fits-all specification consists of three parts.[2] | A complete specification consists of a platform-specific specification which references a common four-part TPM 2.0 library.[28][3] Platform-specific specifications define what parts of the library are mandatory, optional, or banned for that platform; and detail other requirements for that platform.[28] Platform-specific specifications include PC Client,[29] mobile,[30] and Automotive-Thin.[31] |

| Algorithms | SHA-1 and RSA are required.[32] AES is optional.[32] Triple DES was once an optional algorithm in earlier versions of TPM 1.2,[33] but has been banned in TPM 1.2 version 94.[34] The MGF1 hash-based mask generation function that is defined in PKCS#1 is required.[32] | The PC Client Platform TPM Profile (PTP) Specification requires SHA-1 and SHA-256 for hashes; RSA, ECC using the Barreto-Naehrig 256-bit curve and the NIST P-256 curve for public-key cryptography and asymmetric digital signature generation and verification; HMAC for symmetric digital signature generation and verification; 128-bit AES for symmetric-key algorithm; and the MGF1 hash-based mask generation function that is defined in PKCS#1 are required by the TCG PC Client Platform TPM Profile (PTP) Specification.[35] Many other algorithms are also defined but are optional.[36] Note that Triple DES was readded into TPM 2.0, but with restrictions some values in any 64-bit block.[37] |

| Crypto Primitives | A random number generator, a public-key cryptographic algorithm, a cryptographic hash function, a mask generation function, digital signature generation and verification, and Direct Anonymous Attestation are required.[32] Symmetric-key algorithms and exclusive or are optional.[32] Key generation is also required.[38] | A random number generator, public-key cryptographic algorithms, cryptographic hash functions, symmetric-key algorithms, digital signature generation and verification, mask generation functions, exclusive or, and ECC-based Direct Anonymous Attestation using the Barreto-Naehrig 256-bit curve are required by the TCG PC Client Platform TPM Profile (PTP) Specification.[35] The TPM 2.0 common library specification also requires key generation and key derivation functions.[39] |

| Hierarchy | One (storage) | Three (platform, storage and endorsement) |

| Root Keys | One (SRK RSA-2048) | Multiple keys and algorithms per hierarchy |

| Authorization | HMAC, PCR, locality, physical presence | Password, HMAC, and policy (which covers HMAC, PCR, locality, and physical presence). |

| NV RAM | Unstructured data | Unstructured data, Counter, Bitmap, Extend |

The TPM 2.0 policy authorization includes the 1.2 HMAC, locality, physical presence, and PCR. It adds authorization based on an asymmetric digital signature, indirection to another authorization secret, counters and time limits, NVRAM values, a particular command or command parameters, and physical presence. It permits the ANDing and ORing of these authorization primitives to construct complex authorization policies.[40]

Criticism

TCG has faced resistance to the deployment of this technology in some areas, where some authors see possible uses not specifically related to Trusted Computing, which may raise privacy concerns. The concerns include the abuse of remote validation of software (where the manufacturer—and not the user who owns the computer system—decides what software is allowed to run) and possible ways to follow actions taken by the user being recorded in a database, in a manner that is completely undetectable to the user.[41]

The TrueCrypt disk encryption utility, as well as its derivative VeraCrypt, do not support TPM. The original TrueCrypt developers were of the opinion that the exclusive purpose of the TPM is "to protect against attacks that require the attacker to have administrator privileges, or physical access to the computer". The attacker who has physical or administrative access to a computer can circumvent TPM, e.g., by installing a hardware keystroke logger, by resetting TPM, or by capturing memory contents and retrieving TPM-issued keys. As such, the condemning text goes so far as to claim that TPM is entirely redundant.[42] The VeraCrypt publisher has reproduced the original allegation with no changes other than replacing "TrueCrypt" with "VeraCrypt".[43]

Attacks

In 2010, Christopher Tarnovsky presented an attack against TPMs at Black Hat Briefings, where he claimed to be able to extract secrets from a single TPM. He was able to do this after 6 months of work by inserting a probe and spying on an internal bus for the Infineon SLE 66 CL PC.[44][45]

In 2015, as part of the Snowden revelations, it was revealed that in 2010 a US CIA team claimed at an internal conference to have carried out a differential power analysis attack against TPMs that was able to extract secrets.[46][47]

In 2018, a design flaw in the TPM 2.0 specification for the static root of trust for measurement (SRTM) was reported (CVE-2018-6622). It allows an adversary to reset and forge platform configuration registers which are designed to securely hold measurements of software that are used for bootstrapping a computer.[48] Fixing it requires hardware-specific firmware patches.[48] An attacker abuses power interrupts and TPM state restores to trick TPM into thinking that it is running on non-tampered components.[49]

Main Trusted Boot (tboot) distributions before November 2017 are affected by a dynamic root of trust for measurement (DRTM) attack CVE-2017-16837, which affects computers running on Intel's Trusted eXecution Technology (TXT) for the boot-up routine.[49]

In case of physical access, computers with TPM are vulnerable to cold boot attacks as long as the system is on or can be booted without a passphrase from shutdown or hibernation, which is the default setup for Windows computers with BitLocker full disk encryption.[50]

2017 weak key generation controversy

In October 2017, it was reported that a code library developed by Infineon, which had been in widespread use in its TPMs, contained a vulnerability, known as ROCA, which allowed RSA private keys to be inferred from public keys. As a result, all systems depending upon the privacy of such keys were vulnerable to compromise, such as identity theft or spoofing.[51]

Cryptosystems that store encryption keys directly in the TPM without blinding could be at particular risk to these types of attacks, as passwords and other factors would be meaningless if the attacks can extract encryption secrets.[52]

Availability

Currently TPM is used by nearly all PC and notebook manufacturers, primarily offered on professional product lines.

TPM is implemented by several vendors:

- In 2006, with the introduction of first Macintosh models with Intel processors, Apple started to ship Macs with TPM. Apple never provided an official driver, but there was a port under GPL available.[53] Apple has not shipped a computer with TPM since 2006.[54]

- Atmel manufactures TPM devices that it claims to be compliant to the Trusted Platform Module specification version 1.2 revision 116 and offered with several interfaces (LPC, SPI, and I2C), modes (FIPS 140-2 certified and standard mode), temperature grades (commercial and industrial), and packages (TSSOP and QFN).[55][56] Atmel's TPMs support PCs and embedded devices.[55] Atmel also provides TPM development kits to support integration of its TPM devices into various embedded designs.[57]

- Google includes TPMs in Chromebooks as part of their security model.[58]

- Google Compute Engine offers virtualized TPMs (vTPMs) as part of Google Cloud's Shielded VMs product.[59]

- Infineon provides both TPM chips and TPM software, which is delivered as OEM versions with new computers, as well as separately by Infineon for products with TPM technology which complies to TCG standards. For example, Infineon licensed TPM management software to Broadcom Corp. in 2004.[60]

- Microsoft operating systems Windows Vista and later use the chip in conjunction with the included disk encryption component named BitLocker. Microsoft had announced that from January 1, 2015 all computers will have to be equipped with a TPM 2.0 module in order to pass Windows 8.1 hardware certification.[61] However, in a December 2014 review of the Windows Certification Program this was instead made an optional requirement. However, TPM 2.0 is required for connected standby systems.[62] Virtual machines running on Hyper-V can have their own virtual TPM module starting with Windows 10 1511 and Windows Server 2016.[63]

- In 2011, Taiwanese manufacturer MSI launched its Windpad 110W tablet featuring an AMD CPU and Infineon Security Platform TPM, which ships with controlling software version 3.7. The chip is disabled by default but can be enabled with the included, pre-installed software.[64]

- Nuvoton provides TPM devices implementing Trusted Computing Group (TCG) version 1.2 and 2.0 specifications for PC applications. Nuvoton also provides TPM devices implementing these specifications for embedded systems and IoT (Internet of Things) applications via I2C and SPI host interfaces. Nuvoton's TPM complies with Common Criteria (CC) with assurance level EAL 4 augmented, FIPS 140-2 level 1 and TCG Compliance requirements, all supported within a single device.

- Oracle ships TPMs in their recent X- and T-Series Systems such as T3 or T4 series of servers.[65] Support is included in Solaris 11.[66]

- PrivateCore vCage uses TPM chips in conjunction with Intel Trusted Execution Technology (TXT) to validate systems on bootup.

- VMware ESXi hypervisor has supported TPM since 4.x, and from 5.0 it is enabled by default.[67][68]

- Xen hypervisor has support of virtualized TPMs. Each guest gets its own unique, emulated, software TPM.[69]

- KVM, combined with QEMU, has support for virtualized TPMs. As of 2012, it supports passing through the physical TPM chip to a single dedicated guest. QEMU 2.11 released on December 2017 also provides emulated TPMs to guests.[70]

There are also hybrid types; for example, TPM can be integrated into an Ethernet controller, thus eliminating the need for a separate motherboard component.[71][72]

The Trusted Platform Module 2.0 (TPM 2.0) is supported by the Linux kernel since version 3.20.[73][74][75]

See also

- ARM TrustZone

- Intel Management Engine

- Hardware security

- Hardware security module

- Hengzhi chip

- Next-Generation Secure Computing Base

- Threat model

- Trusted Computing

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI)

References

- "ISO/IEC 11889-1:2009 – Information technology – Trusted Platform Module – Part 1: Overview". ISO.org. International Organization for Standardization. May 2009.

- "Trusted Platform Module (TPM) Specifications". Trusted Computing Group. March 1, 2011.

- "TPM Library Specification 2.0". Trusted Computing Group. October 1, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- "Errata for TPM Library Specification 2.0". Trusted Computing Group. June 1, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- Alin Suciu, Tudor Carean (2010). "Benchmarking the True Random Number Generator of TPM Chips". arXiv:1008.2223 [cs.CR].

- TPM Main Specification Level 2 (PDF), Part 1 – Design Principles (Version 1.2, Revision 116 ed.), retrieved September 12, 2017,

Our definition of the RNG allows implementation of a Pseudo Random Number Generator (PRNG) algorithm. However, on devices where a hardware source of entropy is available, a PRNG need not be implemented. This specification refers to both RNG and PRNG implementations as the RNG mechanism. There is no need to distinguish between the two at the TCG specification level.

- "tspi_data_bind(3) – Encrypts data blob" (Posix manual page). Trusted Computing Group. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- TPM Main Specification Level 2 (PDF), Part 3 – Commands (Version 1.2, Revision 116 ed.), Trusted Computing Group, retrieved June 22, 2011

- "TPM – Trusted Platform Module". IBM. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016.

- Instruction 8500.01 (PDF). US Department of Defense. March 14, 2014. p. 43.

- "LUKS support for storing keys in TPM NVRAM". github.com. 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- Greene, James (2012). "Intel Trusted Execution Technology" (PDF) (white paper). Intel. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- Autonomic and Trusted Computing: 4th International Conference (Google Books). ATC. 2007. ISBN 9783540735465. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- Pearson, Siani; Balacheff, Boris (2002). Trusted computing platforms: TCPA technology in context. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-009220-5.

- "SetPhysicalPresenceRequest Method of the Win32_Tpm Class". Microsoft. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- "TPM Certified Products List". Trusted Computing Group. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- "TCG Vendor ID Registry" (PDF). September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- Lich, Brian; Browers, Nick; Hall, Justin; McIlhargey, Bill; Farag, Hany (October 27, 2017). "TPM Recommendations". Microsoft Docs. Microsoft.

- "Trusted Platform Module 2.0: A Brief Introduction" (PDF). Trusted Computing Group. October 13, 2016.

- GitHub - microsoft/ms-tpm-20-ref: Reference implementation of the TCG Trusted Platform Module 2.0 specification.

- Intel Open-Sources New TPM2 Software Stack - Phoronix

- https://github.com/tpm2-software

- The TPM2 Software Stack: Introducing a Major Open Source Release | Intel® Software

- Open source TPM 2.0 software stack eases security adoption

- Infineon Enables Open Source Software Stack for TPM 2.0

- IBM's Software TPM 2.0 download | SourceForge.net

- "Part 1: Architecture" (PDF), Trusted Platform Module Library, Trusted Computing Group, October 30, 2014, retrieved October 27, 2016

- Arthur, Will; Challener, David; Goldman, Kenneth (2015). A Practical Guide to TPM 2.0: Using the New Trusted Platform Module in the New Age of Security. New York City: Apress Media, LLC. p. 69. doi:10.1007/978-1-4302-6584-9. ISBN 978-1430265832.

- "PC Client Protection Profile for TPM 2.0 – Trusted Computing Group". trustedcomputinggroup.org.

- "TPM 2.0 Mobile Reference Architecture Specification – Trusted Computing Group". trustedcomputinggroup.org.

- "TCG TPM 2.0 Library Profile for Automotive-Thin". trustedcomputinggroup.org. March 1, 2015.

- http://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TPM-Main-Part-2-TPM-Structures_v1.2_rev116_01032011.pdf

- http://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/mainP2Struct_rev85.pdf

- http://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TPM-main-1.2-Rev94-part-2.pdf

- https://www.trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/PC-Client-Specific-Platform-TPM-Profile-for-TPM-2-0-v43-150126.pdf

- https://www.trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TCG_Algorithm_Registry_Rev_1.22.pdf

- https://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TCG-_Algorithm_Registry_Rev_1.27_FinalPublication.pdf

- http://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TPM-Main-Part-1-Design-Principles_v1.2_rev116_01032011.pdf

- https://www.trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/TPM-Rev-2.0-Part-1-Architecture-01.16.pdf

- "Section 23: Enhanced Authorization (EA) Commands", Trusted Platform Module Library; Part 3: Commands (PDF), Trusted Computing Group, March 13, 2014, retrieved September 2, 2014

- Stallman, Richard Matthew, "Can You Trust Your Computer", Project GNU, Philosophy, Free Software Foundation

- "TrueCrypt User Guide" (PDF). truecrypt.org. TrueCrypt Foundation. February 7, 2012. p. 129 – via grc.com.

- "FAQ". veracrypt.fr. IDRIX. July 2, 2017.

- "Black Hat: Researcher claims hack of processor used to secure Xbox 360, other products". January 30, 2012. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Szczys, Mike (February 9, 2010). "TPM crytography cracked". HACKADAY. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010.

- Scahill, Jeremy ScahillJosh BegleyJeremy; Begley2015-03-10T07:35:43+00:00, Josh (March 10, 2015). "The CIA Campaign to Steal Apple's Secrets". The Intercept. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- "TPM Vulnerabilities to Power Analysis and An Exposed Exploit to Bitlocker – The Intercept". The Intercept. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Seunghun, Han; Wook, Shin; Jun-Hyeok, Park; HyoungChun, Kim (August 15–17, 2018). A Bad Dream: Subverting Trusted Platform Module While You Are Sleeping (PDF). 27th USENIX Security Symposium. Baltimore, MD, USA: USENIX Association. ISBN 978-1-939133-04-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 20, 2019.

- Catalin Cimpanu (August 29, 2018). "Researchers Detail Two New Attacks on TPM Chips". Bleeping Computer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Melissa Michael (October 8, 2018). "Episode 14| Reinventing the Cold Boot Attack: Modern Laptop Version" (Podcast). F-Secure Blog. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Goodin, Dan (October 16, 2017). "Millions of high-security crypto keys crippled by newly discovered flaw". Ars Technica. Condé Nast.

- "Can the NSA Break Microsoft's BitLocker? – Schneier on Security". www.schneier.com. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Singh, Amit, "Trusted Computing for Mac OS X", OS X book.

- "Your Laptop Data Is Not Safe. So Fix It". PC World. January 20, 2009.

- "Home – Microchip Technology". www.atmel.com.

- "AN_8965 TPM Part Number Selection Guide – Application Notes – Microchip Technology Inc" (PDF). www.atmel.com.

- "Home – Microchip Technology". www.atmel.com.

- "Chromebook security: browsing more securely". Chrome Blog. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "Shielded VMs". Google Cloud. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Trusted Platform Module (TPM) im LAN-Adapter". Heise Online. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "Windows Hardware Certification Requirements". Microsoft.

- "Windows Hardware Certification Requirements for Client and Server Systems". Microsoft.

- "What's new in Hyper-V on Windows Server 2016". Microsoft.

- "TPM. Complete protection for peace of mind". Winpad 110W. MSI.

- "Oracle Solaris and Oracle SPARC T4 Servers— Engineered Together for Enterprise Cloud Deployments" (PDF). Oracle. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- "tpmadm" (manpage). Oracle. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- Security and the Virtualization Layer, VMware.

- Enabling Intel TXT on Dell PowerEdge Servers with VMware ESXi, Dell.

- "XEN Virtual Trusted Platform Module (vTPM)". Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- "QEMU 2.11 Changelog". qemu.org. December 12, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- "Replacing Vulnerable Software with Secure Hardware: The Trusted Platform Module (TPM) and How to Use It in the Enterprise" (PDF). Trusted computing group. 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- "NetXtreme Gigabit Ethernet Controller with Integrated TPM1.2 for Desktops". Broadcom. May 6, 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- TPM 2.0 Support Sent In For The Linux 3.20 Kernel - Phoronix

- TPM 2.0 Support Continues Maturing In Linux 4.4 - Phoronix

- With Linux 4.4, TPM 2.0 Gets Into Shape For Distributions - Phoronix

Further reading

- TPM 1.2 Protection Profile (Common Criteria Protection Profile), Trusted Computing Group.

- PC Client Platform TPM Profile (PTP) Specification (Additional TPM 2.0 specifications as applied to TPMs for PC clients), Trusted Computing Group.

- PC Client Protection Profile for TPM 2.0 (Common Criteria Protection Profile for TPM 2.0 as applied to PC clients), Trusted Computing Group.

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM) (Work group web page and list of resources), Trusted Computing Group.

- "OLS: Linux and trusted computing", LWN.

- Trusted Platform Module (podcast), GRC, 24:30.

- TPM Setup (for Mac OS X), Comet way.

- "The Security of the Trusted Platform Module (TPM): statement on Princeton Feb 26 paper" (PDF), Bulletin (press release), Trusted Computing Group, February 2008.

- "Take Control of TCPA", Linux journal.

- TPM Reset Attack, Dartmouth.

- Trusted Platforms (white paper), Intel, IBM Corporation, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.161.7603.

- Garrett, Matthew, A short introduction to TPMs, Dream width.

- Martin, Andrew, Trusted Infrastructure "101" (PDF), PSU.

- Using the TPM: Machine Authentication and Attestation (PDF), Intro to trusted computing, Open security training.

- A Root of Trust for Measurement: Mitigating the Lying Endpoint Problem of TNC (PDF), CH: HSR, 2011.