T. Rex (band)

T. Rex were an English rock band, formed in 1967 by singer-songwriter and guitarist Marc Bolan. The band was initially called Tyrannosaurus Rex, and released four psychedelic folk albums under this name. In 1969, Bolan began to change the band's style towards electric rock, and shortened their name to T. Rex the following year. This development culminated in 1970's "Ride a White Swan", and the group soon became pioneers of the glam rock movement.

T. Rex | |

|---|---|

T. Rex during their heyday (left to right): Bill Legend, Mickey Finn, Marc Bolan, Steve Currie | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | London, England, United Kingdom |

| Genres |

|

| Years active | 1967–1977 |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Past members | Marc Bolan Steve Peregrin Took Mickey Finn Steve Currie Bill Legend Paul Fenton Gloria Jones Jack Green Dino Dines Davy Lutton Miller Anderson Herbie Flowers Tony Newman |

From 1970 to 1973, T. Rex encountered a popularity in the UK comparable to that of the Beatles, with a run of eleven singles in the UK top ten. They scored four UK number one hits, "Hot Love", "Get It On", "Telegram Sam" and "Metal Guru". The band's 1971 album Electric Warrior received critical acclaim as a pioneering glam rock album. It reached number 1 in the UK. The 1972 follow-up, The Slider, entered the top 20 in the US. Following the release of "20th Century Boy" in 1973, which reached number three in the UK, T. Rex's appeal began to wane, though the band continued releasing one album per year.

In 1977, founder, songwriter and sole constant member Bolan died in a car crash several months after the release of the group's final studio album Dandy in the Underworld, and the group disbanded. T. Rex have continued to influence a variety of subsequent artists. The band will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020.[1]

History

Formation and psychedelic folk

Marc Bolan founded Tyrannosaurus Rex in July 1967, following a handful of failed solo singles and a brief career as lead guitarist in psych-rock band John's Children. After a solitary disastrous performance as a four-piece electric rock band on 22 July at the Electric Garden in London's Covent Garden alongside drummer Steve Porter plus two older musicians: guitarist Ben Cartland and an unknown bassist, the group immediately broke up.[2][3] Subsequently, Bolan retained the services of Porter, who switched to percussion under the name Steve Peregrin Took, and the two began performing acoustic material as a duo with a repertoire of folk-influenced Bolan-penned songs. After seeing an influential performance by Ravi Shankar, the band adopted a stage manner resembling the performance of traditional Indian music.[3][4] The combination of Bolan's acoustic guitar and distinctive vocal style with Took's bongos and assorted percussion—which often included children's instruments such as the Pixiphone—earned them a devoted following in the thriving hippy underground scene. BBC Radio One Disc jockey John Peel championed the band early in their recording career.[5] Peel later appeared on record with them, reading stories written by Bolan. Another key collaborator was producer Tony Visconti, who went on to produce the band's albums well into their second, glam rock phase.[6]

During 1968–1969, Tyrannosaurus Rex had become a modest success on radio and on record, and they released three albums, the third of which, Unicorn, came within striking distance of the UK Top 10 Albums. While Bolan's early solo material was rock and roll-influenced pop music, by now he was writing dramatic and baroque songs with lush melodies and surreal lyrics filled with Greek and Persian mythology as well as poetic creations of his own. The band became regulars on Peel Sessions on BBC radio, and toured Britain's student union halls.[7]

By 1969 there was a rift developing between the two halves of Tyrannosaurus Rex. Bolan and his girlfriend June Child were living a quiet life, Bolan working on his book of poetry entitled The Warlock of Love and concentrating on his songs and performance skills. Took, however, had fully embraced the anti-commercial, drug-taking ethos of the UK Underground scene centred around Ladbroke Grove. Took was also attracted to anarchic elements such as Mick Farren/Deviants and members of the Pink Fairies Rock 'n' Roll and Drinking Club.[8] Took also began writing his own songs, and wanted the duo to perform them, but Bolan strongly disapproved of his bandmate's efforts, rejecting them for the duo's putative fourth album, in production in Spring/Summer 1969. In response to Bolan's rebuff, Took contributed two songs as well as vocals and percussion to Twink's Think Pink album.[9]

Bolan's relationship with Took ended after this, although they were contractually obliged to go through with a US tour which was doomed before it began. Poorly promoted and planned, the acoustic duo were overshadowed by the loud electric acts they were billed with. To counter this, Took drew from the shock rock style of Iggy Pop; Took explained, "I took my shirt off in the Sunset Strip where we were playing and whipped myself till everybody shut up. With a belt, y'know, a bit of blood and the whole of Los Angeles shuts up. 'What's going on, man, there's some nutter attacking himself on stage.' I mean, Iggy Stooge had the same basic approach."[10]

As soon as Bolan returned to the UK, he replaced Took with percussionist Mickey Finn.[6] and they completed the fourth album, released in early 1970 as A Beard of Stars, the final album under the Tyrannosaurus Rex moniker.

Glam rock and commercial success

As well as progressively shorter titles, Tyrannosaurus Rex's albums began to show higher production values, more accessible songwriting from Bolan, and experimentation with electric guitars and a true rock sound.[11] A breakthrough had been "King of the Rumbling Spires" (recorded with Took and released in summer 1969 shortly prior to his departure), which used a full rock band setup, and the electric sound had been further explored on A Beard of Stars. The group's next album, T. Rex, continued the process of simplification by shortening the name[12], and completed the move to electric guitars.[11] Visconti supposedly got fed up with writing the name out in full on studio charts and tapes and began to abbreviate it; when Bolan first noticed he was angry but later claimed the idea was his. The new sound was more pop-oriented, and the first single, "Ride a White Swan" released in October 1970 made the Top 10 in the UK by late November and reached number two in January 1971. In early 1971, T. Rex reached the top 20 of the UK Albums Chart.[12]

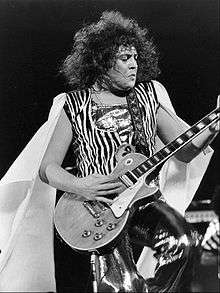

"Ride a White Swan" was quickly followed by a second single, "Hot Love", which reached the top spot on the UK charts, and remained there for six weeks. A full band, which featured bassist Steve Currie and drummer Bill Legend, was formed to tour to growing audiences, as teenagers began replacing the hippies of old.[6] After Chelita Secunda added two spots of glitter under Bolan's eyes before an appearance on Top of the Pops, the ensuing performance would often be viewed as the birth of glam rock. After Bolan's display, glam rock would gain popularity in the UK and Europe during 1971–72. T. Rex's move to electric guitars coincided with Bolan's more overtly sexual lyrical style and image. The group's new image and sound outraged some of Bolan's older hippie fans, who branded him a "sell-out". Some of the lyrical content of Tyrannosaurus Rex remained, but the poetic, surrealistic lyrics were now interspersed with sensuous grooves, orgiastic moans and innuendo.

In September 1971, T. Rex released their second album Electric Warrior, which featured Currie and Legend. Often considered to be their best album, the chart-topping Electric Warrior brought much commercial success to the group; publicist BP Fallon coined the term "T. Rextasy" as a parallel to Beatlemania to describe the group's popularity.[13] The album included T. Rex's best-known song, "Get It On", which hit number one in the UK. In January 1972 it became a top ten hit in the US, where the song was retitled "Bang a Gong (Get It On)" to distinguish it from a 1971 song by the group Chase. Along with several Sweet hits, "Get It On" was among the few British glam rock songs that were successful in the US.[14] However, the album still recalled Bolan's acoustic roots with ballads such as "Cosmic Dancer" and the stark "Girl". Soon after, Bolan left Fly Records; after his contract had lapsed, the label released the album track "Jeepster" as a single without his permission. Bolan went to EMI, where he was given his own record label in the UK—T. Rex Records, the "T. Rex Wax Co.".[3]

On 18 March 1972, T. Rex played two shows at the Empire Pool, Wembley, which were filmed by Ringo Starr and his crew for Apple Films. A large part of the second show was included on Bolan's own rock film Born to Boogie, while bits and pieces of the first show can be seen throughout the film's end-credits. Along with T. Rex and Starr, Born to Boogie also features Elton John, who jammed with the friends to create rocking studio versions of "Children of the Revolution" and "Tutti Frutti".

T. Rex's third album The Slider was released in July 1972. The band's most successful album in the US, The Slider was not as successful as its predecessor in the UK, where it peaked at number four. During spring/summer 1972, Bolan's old label Fly released the chart-topping compilation album Bolan Boogie, a collection of singles, B-sides and LP tracks, which affected The Slider's sales. Two singles from The Slider, "Telegram Sam" and "Metal Guru", became number one hits in the UK. Born to Boogie premiered at the Oscar One cinema in London, in December 1972. The film received negative reviews from critics, while it was loved by fans.

Transition, decline and resurgence

Tanx would mark the end of the classic T. Rex line-up. An eclectic album containing several melancholy ballads and rich production, Tanx showcased the T. Rex sound bolstered by extra instrumental embellishments such as Mellotron and saxophone. "The Street and Babe Shadow" was funkier while the last song "Left Hand Luke and the Beggar Boys" was seen by critics as a nod to gospel with several female backing singers.[15] Released two months later in March 1973, "20th Century Boy" was another important success, peaking at number 3 in the UK Singles chart but was not included in the album.[16] It marked the end of the golden era in which T. Rex scored 11 singles in a row in the UK top ten.

During the recording T. Rex members began to quit, starting with Bill Legend in November. Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow was released on 1 February 1974, and reached number 12 in the UK. The album harkened back to the Tyrannosaurus Rex days with long song titles and lyrical complexity, but was not a critical success. In the US, Warner Brothers dropped the band without releasing the album. T. Rex by now had an extended line-up which included second guitarist Jack Green and B. J. Cole on pedal steel. Soon after the album's release, Bolan split with producer Visconti, then in December 1974, Finn also left the band. A single, "Zip Gun Boogie", appeared in late 1974 credited as a Marc Bolan solo effort (though still on the T. Rex label). It only reached UK No. 41, and the T. Rex band identity was quickly re-established.

The T. Rex album Bolan's Zip Gun (1975) was self-produced by Bolan who, in addition to writing the songs, gave his music a harder, more futuristic sheen. The final song recorded with Visconti, "Till Dawn", was re-recorded for Bolan's Zip Gun with Bolan at the controls. Bolan's own productions were not well received in the music press. Most of Zip Gun plus three tracks from Zinc Alloy had already been released in the US as Light of Love, by replacement label Casablanca Records who had refused Zinc Alloy in favour of new material. Rolling Stone magazine gave it a positive review,[17] but the British press slammed T. Rex for copying Bowie's The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, even though Marc had spoken of releasing work under the pseudonym "Zinc Alloy" during the mid-1960s. Always a fantasist with "the biggest ego of any rock star ever",[13] during this time Bolan became increasingly isolated, while high tax rates in the UK drove him into exile in Monte Carlo and the US. No longer a vegetarian, Bolan put on weight due to consumption of hamburgers and alcohol, and was ridiculed in the music press.

T. Rex's penultimate album, Futuristic Dragon (1976), featured a schizophrenic production style that veered from Wall of Sound-style songs to disco backing, with nostalgic nods to the old T. Rex boogie machine. It only managed to reach number 50, but the album was better received by the critics and featured the singles "New York City" (number 15 in the UK) and "Dreamy Lady" (number 30). The latter was promoted as T. Rex Disco Party. To promote the album, T. Rex toured the UK, and performed on television shows such as Top of the Pops, Supersonic and Get It Together.

In the summer of 1976, T. Rex released two more singles, "I Love to Boogie" (which charted at number 13) and "Laser Love", which made number 42. In early 1977 Dandy in the Underworld was released to critical acclaim. Bolan had slimmed down and regained his elfin looks, and the songs too had a stripped-down, streamlined sound. A spring UK tour with punk band The Damned on support garnered positive reviews. As Bolan was enjoying a new surge in popularity, he talked about performing again with Finn and Took, as well as reuniting with Visconti.

Bolan's death and disbandment

Marc Bolan and his girlfriend Gloria Jones spent the evening of 15 September 1977 drinking at the Speakeasy and then dining at Morton's club on Berkeley Square, in Mayfair, Central London.[18] While driving home early in the morning of 16 September, Jones crashed Bolan's purple Mini 1275 GT into a tree (now the site of Bolan's Rock Shrine), after failing to negotiate a small humpback bridge near Gipsy Lane on Queens Ride, Barnes, southwest London, a few miles from his home at 142 Upper Richmond Road West in East Sheen.[19] While Jones was severely injured, Bolan was killed in the crash, two weeks before his 30th birthday.[20]

As Bolan had been the only constant member of T. Rex and also the only composer and writer, his death ultimately ended the band. Only Legend survives from the band prior to its commercial decline; Took went on to found Pink Fairies and appear on Mick Farren's solo album Mona – The Carnivorous Circus before spending the 1970s working mostly on his own material, either solo or fronting bands such as Shagrat (1970–1971) and Steve Took's Horns (1977–1978).[21] He died in 1980 from asphyxiation caused by choking on a cocktail cherry,[22] The following year Currie, who had played for Chris Spedding before moving to Portugal in 1979, died there in a car crash.[23] Finn played as a session musician for The Soup Dragons and The Blow Monkeys before his death in 2003 of possible liver and kidney failure.[24]

Influence and legacy

T. Rex vastly influenced several genres over several decades including glam rock, the punk movement, post-punk, indie pop, britpop and alternative rock. They were cited by acts such as New York Dolls, the Ramones, Kate Bush, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division, R.E.M., the Smiths, the Pixies and Tricky.

Sylvain Sylvain of the New York Dolls said that when forming his band with Billy Murcia and Johnny Thunders: "[they]'d all sit on the bed with these cheap guitars and do Marc Bolan songs, as well as some blues and instrumentals".[25] Sparks were inspired at their beginnings by Tyrannosaurus Rex, pre-T. Rex:[26] seeing them live "was really our education" stated Ron Mael.[27] Joey Ramone of the Ramones said about Bolan: "I get into people who are unique and innovative and have colour. That's why I love Marc Bolan. There was something so mystical about him, his singing voice, his manner. His songs really move ya, they're so moving and dark."[28] Siouxsie and the Banshees released a cover version of "20th Century Boy" early in their career in 1979. Joy Division's Bernard Sumner was marked by the sound of the guitar of early T. Rex; his musical journey began at a poppy level with "Ride a White Swan".[29] The Slits' guitarist Viv Albertine was fascinated by Bolan's guitar playing: "It was [...] the first time I ever listened to a guitar part. Because back then girls didn't really listen to guitar parts, it was a guy's thing. And guitars were really macho things then and I couldn't bear say, Hendrix's guitar playing, it was too in your face and too threateningly sexual, whereas Marc Bolan's guitar playing was kind of cartoony. And I could sing the parts. They weren't virtuoso, they were funny, they were humourous [sic] guitar parts."[30] Smiths' composer and guitarist Johnny Marr stated: "T. Rex was pure pop".[31] "The influence of T. Rex is very profound on certain songs of the Smiths like "Panic" and "Shoplifters of the World Unite". Lead singer Morrissey also admired Bolan. While writing "Panic" he was inspired by "Metal Guru" and wanted to sing in the same style. He didn't stop singing it in an attempt to modify the words of "Panic" to fit the exact rhythm of "Metal Guru". Marr later stated: "He also exhorted me to use the same guitar break so that the two songs are the same!"[32] Marr rated Bolan in his ten favourite guitarists.[33] Prefab Sprout's Paddy McAloon cited "Ride a White Swan" as "the song that vindicated my love of pop".[34] R.E.M. covered live "20th Century Boy" early in their career in 1984:[35] singer Michael Stipe said that T. Rex and other groups of the 1970s "were huge influences on all of us",[36] "[they] really impacted me".[37]

The Pixies's lead guitarist Joey Santiago cited Electric Warrior in his 13 defining records,[38] as did the Jam's Paul Weller.[39] Santiago said: "Bolan took the blues and made it a lot more palatable".[38] Kate Bush listened to Bolan during her teenage years and then mentioned his name in the lyrics of the song "Blow Away (for Bill)".[40] Nick Cave covered live "Cosmic Dancer",[41] commenting that Electric Warrior contained "some of the greatest lyrics ever written",[42] further adding, it was "my favorite record, [...] the songs are so beautiful, it is an extraordinary record".[43] Tricky cited Bolan as "totally unique and ahead of his time".[44] When talking about his favourite albums, PJ Harvey's collaborator John Parish said that T. Rex "is the place to start", adding that "this band and that album [Electric Warrior] was what got me into music in the first place". When he saw T. Rex on Top of the Pops playing "Jeepster", he felt: "that's my kind of music [...] The thing I related to as 12-year-old I still go back to and uses as one of my main touchstones when I'm making records".[45] Parish explained, "I've been listening to T-Rex pretty consistently since 1971".[46] Oasis "borrowed" the distinct guitar riff from "Get It On" on their single "Cigarettes & Alcohol".[47] Oasis's guitarist, Noel Gallagher, has cited T. Rex as a strong influence.[48] The early acoustic material was influential in helping to bring about progressive rock and 21st century folk music-influenced singers as Devendra Banhart,[49] whom said: "I love Tyrannosaurus Rex so much, it’s so easy to love, so righteous to love, and so natural to love, I can’t imagine anyone not liking it."[50]

T. Rex are referenced in several popular songs, including David Bowie's "All the Young Dudes" (which he wrote for Mott the Hoople in 1972),[51] the Ramones' "Do You Remember Rock 'n' Roll Radio?",[52] Serge Gainsbourg's "Ex-Fan Des Sixties",[53] the Who's "You Better You Bet",[54] B A Robertson's "Kool in the Kaftan",[55] R.E.M.'s "The Wake-Up Bomb",[56] and My Chemical Romance's "Vampire Money".[57] The music of T. Rex features in the soundtracks of various movies, including Velvet Goldmine,[58] Death Proof,[59] Billy Elliot,[60] the Bank Job,[61] Dallas Buyers Club,[62] and Baby Driver.[63] The sleeve of The Slider album can be seen in the Lindsay Anderson movie O Lucky Man!,[64] and in Tim Burton's Dark Shadows.[65] In Miha Mazzini's novel King of the Rattling Spirits, the narrator starts remembering his childhood when he sees Tyrannosaurus Rex record "King of Rumbling Spires" in the record store and realizes he has mistakenly remembered the title as "King of the Rattling Spirits".[66]

Discography

As Tyrannosaurus Rex

- My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968)

- Prophets, Seers & Sages: The Angels of the Ages (1968)

- Unicorn (1969)

- A Beard of Stars (1970)

As T. Rex

- T. Rex (1970)

- Electric Warrior (1971)

- The Slider (1972)

- Tanx (1973)

- Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow (1974)

- Bolan's Zip Gun (1975)

- Futuristic Dragon (1976)

- Dandy in the Underworld (1977)

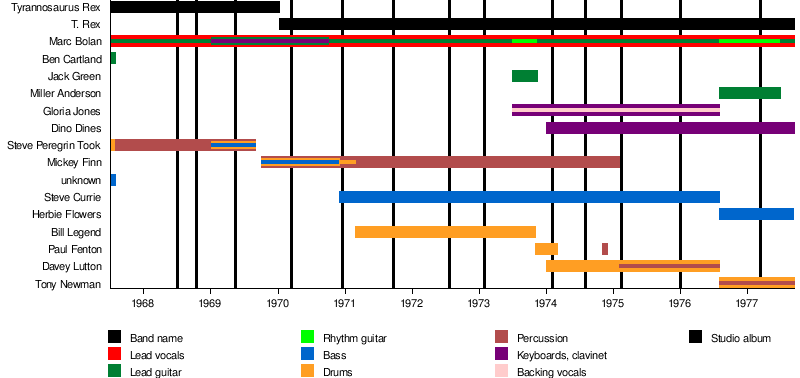

Members

- Marc Bolan – lead/rhythm guitar, lead vocals (July 1967 – Sep 1977; died 1977), also keyboards (Jan 1969-Sept 1970)

- Ben Cartland - guitar (July 1967)

- unknown - bass (July 1967)

- Steve Peregrin Took – percussion, backing vocals(August 1967 – Sep 1969; died 1980), also drums (July 1967, Jan-Sep 1969) bass (Jan – Sep 1969)

- Mickey Finn – percussion, backing vocals (Oct 1969 – Feb 1975; died 2003), also drums (Oct 1969-Mar 1971), and bass (Oct 1969-Dec 1970)

- Steve Currie – bass (Dec 1970 – Aug 1976; died 1981)

- Bill Legend – drums (Mar 1971 – Nov 1973)

- Gloria Jones – keyboards, tambourine, vocals (Jul 1973 – Aug 1976)

- Jack Green – lead guitar (Jul 1973 – Nov 1973)

- Dino Dines – keyboards (Jan 1974 – Sep 1977; died 2004)

- Paul Fenton - drums (Dec 1973 – Feb 1974) also percussion (Nov 1974)

- Davey Lutton – drums (Jan 1974 – Aug 1976) also percussion (Feb 1975-Aug 1976)

- Miller Anderson – lead guitar (Aug 1976 – June 1977)

- Herbie Flowers – bass (Aug 1976 – Sep 1977)

- Tony Newman – drums, percussion (Aug 1976 – Sep 1977)

Timeline

See also

- List of 1970s one-hit wonders in the United States

References

- "Class of 2020". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Marc Bolan 1947-1977 A Chronology - Cliff McLenehan, Helter Skelter Publishing 2002, p25

- Paytress, Mark. Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press. 2003

- Auslander, Phillip (2006). Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780472068685. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Stand and Deliver: The Autobiography Pan Macmillan, 2007

- Philip Auslander Performing glam rock: gender and theatricality in popular music University of Michigan Press, 2006

- BBC – Radion 1 – Keeping it Peel – 17/11/1969 BBC Radio One

- "Steve Took's Domain". Steve-took.co.uk. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Sleevenotes by Dave Thompson to CD The Missing Link To Tyrannosaurus Rex Cleopatra Records CLEO 9528-2 1995

- Steve Took - From Bolan Boogie To Gutter Rock, Charles Shaar Murray. NME 14 October 1972

- Legends of rock guitar: the essential reference of rock's greatest guitarists Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997

- Thompson, Dave (2009). Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell: The Dangerous Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop and Lou Reed. New York: Backbeat Books. ISBN 9780879309855.

- Reynolds, Simon (2016). Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the Twenty-first Century. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 9780062279811. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Jeremy Simmonds The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches (Marc Bolan) Chicago Review Press, 2008

- Deusner, Stephen M. (5 February 2006). "T. Rex: Tanx / Zip Gun / Futuristic Dragon / Work in Progress | Album Reviews | Pitchfork". Pitchfork. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- "T. Rex uk charts". officialcharts.com. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Barnes, Ken (26 September 1974). "T. Rex Light of Love". RollingStone. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "How Marc Bolan's death rocked my world". www.shropshirestar.com.

- Bignell, Paul (16 September 2012). "Mystery of Marc Bolan's death solved". The Independent. London. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Stan Hawkins The British pop dandy: masculinity, popular music and culture Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009

- "Auteur to Author - Record Collector Magazine". recordcollectormag.com.

- Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Simon and Schuster. p. 288. ISBN 9780743463300. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Colin King Rock on!: the rock 'n' roll greats p.110. Caxton, 2002

- "Obituary: Mickey Finn, Mickey Finn Percussionist who, as a leading member of T Rex, defined the style of an era and kept the band's name and music alive". The Times. 14 January 2003.

Paytress, Mark (2009). Marc Bolan: The Rise And Fall Of A 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120236. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

"Mickey Finn: Exotic percussionist in at the start of glam rock". The Guardian. 18 January 2003. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

BBC News – Entertainment – T Rex band member dies BBC News (13 January 2003) - Antonia, Nina (1998). The Makeup Breakup of The New York Dolls: Too Much, Too Soon. Omnibus Pr. ASIN B01K3KLAZA.

- Swanson, Dave (11 September 2017). "Sparks Interview". Diffuser. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Roberts, Randall (28 August 2017). "Sparks' Ron and Russell Mael recall getting booted from the Riot Hyatt on Sunset — for throwing a bagel out the window". LA Times. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- True, Everett (2002). Hey Ho Let's Go: The Story of the Ramones. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0711991088.

- Gale, Lee (19 September 2012). "Icon: Bernard Sumner". GQ. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Hasson, Thomas (18 April 2013). "Like Choosing A Lover: Viv Albertine's Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Freeman, John (16 June 2015). "Rubber Rings: Johnny Marr's Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- "Johnny Marr Interview". Les Inrockuptibles. 21 April 1999.

- "Johnny Marr Top Ten Guitarists". Uncut (November 2004).

"Johnny Marr Top Ten Guitarists" Morrissey-solo.com. Retrieved 16 November 2011. - "Prefab Sprout's Paddy McAloon – My Life In Music". Uncut. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- "R.E.M. - 20th Century Boy (Live at Theatre El Dorado, Paris, France 1984)". YouTube. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Schonfeld, Zach (26 September 2014). "Reclaiming Monster: Reflecting on R.E.M.'s Most Misunderstood Album with Michael Stipe". Newsweek. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Hann, Michael (19 January 2018). "I'm a pretty good pop star': Michael Stipe on his favourite REM songs". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Tuffrey, Laurie (22 May 2014). "Planets Of Sound: Joey Santiago Of Pixies' Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Colegate, Mat (7 May 2015). "At His Modjesty's Request: Paul Weller's Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Thomson, Graeme (2012). Kate Bush: Under the Ivy. Omnibus. ISBN 978-1780381466. Bush sings the words: "Bolan and moony are heading the show tonight".

- Trendell, Andrew (20 June 2019). "Conversations With Nick Cave at The Barbican". NME.com. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Nick Cave performing Cosmic Dancer in Amsterdam". Youtube. 26 May 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019

- "Nick Cave covering Cosmic Dancer in Stockholm". Youtube. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019

- "Tricky on Englishness And The Country That Made Me". The Quietus. 5 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Frelon, Luc (2013). "John Parish dans Radio Vinyle #27 sur Fip". Radio France. YouTube. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Interview with John Parish". adequacy.net. 15 October 2002. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- "Oasis biography". Rollingstone.com. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Liam Gallagher: 'David Bowie and T.Rex have inspired my post-Oasis album'. NME. 27 March 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011

- Eccleston, Danny (2 May 2011). "Devendra Banhart Rejoicing In The Hands". Mojo.com. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

Strew, Roque. "Devendra Banhart Cripple Crow review". Stylusmagazine.com. 25 September 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2011. - Dalton, Trinie. "So Righteous to Love: Devendra Banhart". Arthur magazine. May 2004. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Paytress, 2003. David Bowie wrote the words: "Man I need a TV when I've got T.Rex".

- The Ramones sing the words: "Will you remember Jerry Lee, John Lennon, T. Rex and OI Moulty?"

- Serge Gainsbourg namedrops T. Rex next to Elvis Presley in this song written for Jane Birkin in 1978.

- Steven Rosen. "The Who - Uncensored on The Record". Coda Books. 2011. "To the sound of old T. Rex"

- Robertson sings the lyrics: "Go out and buy T Rex Fee fi fiddley do"

- R.E.M. sing the words: "Practice my T-Rex moves and make the scene".

- My Chemical Romance sing: "Glimmers like Bolan in the shining sun"

- Velvet Goldmine. cd 1998 Fontana Records London

- Death Proof (soundtrack), 2007, Maverick records

- "Billy Elliot soundtrack". Allmusic. Retrieved 2 December 2018

- The Bank Job. 2008 Lionsgate. dvd

- Dallas Buyers Club. Truth Entertainment, Voltage Pictures, Focus Features, 2013 dvd

- "Sony sued for using T. Rex song in Baby Driver". news.avclub.com. Retrieved 2 December 2018

- O Lucky Man!. 1973. DVD. Warner Bros.

- Tim Burton. Dark Shadows. 2012. Warner Bros. Pictures

- Miha Mazzini. King of the Rattling Spirits. 2001. Scala House Press

Sources

- Bolan, Marc. The Warlock of Love. Lupus books. 1969

- McLenehan, Cliff. Marc Bolan: 1947–1977 A Chronology. Helter Skelter Publishing. 2002.

- Paytress, Mark. Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press. 2003.

- Paytress, Mark. "Marc Bolan: T. Rextasy". Mojo. May 2005.

- Ewens, Carl. Born to Boogie: The Songwriting of Marc Bolan. Aureus Publishing. 2007.

- Roland, Paul. Cosmic Dancer: The Life & Music of Marc Bolan. Tomahawk Press. 2012.

- Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder 2013