St. Elizabeths Hospital

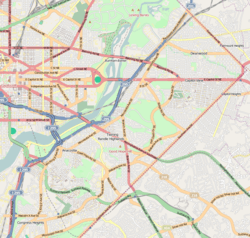

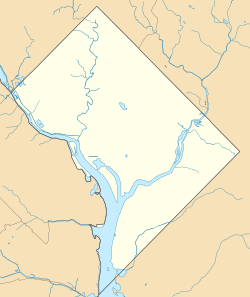

St. Elizabeths Hospital is a psychiatric hospital in Southeast, Washington, D.C. It opened in 1855 as the first federally operated psychiatric hospital in the United States. Housing over 8,000 patients at its peak in the 1950s, the hospital had a fully functioning medical-surgical unit, a school of nursing, accredited internships and psychiatric residencies.[4] Its campus was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990.[3]

St. Elizabeths Hospital | |

Aerial view of the West Campus in 2015, looking south | |

| |

| Location | 2700 and 2701 Martin Luther King, Jr., Avenue, 1100 Alabama Avenue SE Washington, D.C.[1] |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°51′03″N 76°59′40″W |

| Area | 346 acres (140 ha) |

| Built | 1852 |

| Architect | Thomas U. Walter; Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge |

| Architectural style | Italianate Revival, Italian Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 79003101 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 26, 1979[2] |

| Designated NHLD | December 14, 1990[3] |

The hospital was under the control of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services until 1987, when ownership of its east wing was transferred to the District of Columbia.[5] Since 2010, the hospital's functions have been limited to the portion of the east campus operated by the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health. The remainder of the east campus is slated for redevelopment by the District of Columbia, and the west campus is being redeveloped for use as headquarters for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and its subsidiary agencies.[6]

History

Early years and peak operations

St. Elizabeths Hospital was founded in August 1852 when the United States Congress appropriated $100,000 for the construction of a hospital in Washington, D.C., to provide care for indigent residents of the District of Columbia and members of the U.S. Army and Navy with brain illnesses.

In the 1830s, local residents, including Dr. Thomas Miller, a medical doctor and president of the D.C. Board of Health, began petitioning Congress for a facility to care for people with brain diseases in the City of Washington. Their efforts were given a significant boost by Dorothea Dix (1802–1877), a pioneering advocate for people living with mental illnesses who helped convince legislators of the need for the hospital. In 1852 she wrote the legislation that established the hospital.[7] Dix, who was on friendly terms with U.S. President Millard Fillmore, was asked to assist the Interior Secretary in getting the hospital started. Her recommendation resulted in the appointment of Dr. Charles H. Nichols as the hospital's first superintendent. After his appointment in the fall of 1852, Nichols and Dix began formulating a plan for the hospital's design and operation and set out to find an appropriate location, based upon guidelines created by Thomas Story Kirkbride.[8] His 1854 manual recommended specifics such as site, ventilation, number of patients, and the need for a rural location proximate to a city. He also recommended that the location have good soil for farming and gardens for the patients.[7]

Dr. Nichols oversaw the design and building of St. Elizabeths, which began in 1853. The hospital was constructed in three phases. The west wing was built first, followed by the east wing and finally the center portion of the building, which housed the administrative operations as well as the superintendent's residential quarters. All three sections of the hospital existed under one roof, keeping with Kirkbride's design. Two other buildings, the West Lodge (1856–98) for men and the East Lodge for women, were built to house and care for African-American patients.[7]

Soon after the hospital opened to patients in January 1855, it became known officially as the Government Hospital for the Insane. During the Civil War the West Lodge, originally built for male African-American patients, was used as a general hospital by the U.S. Navy. The unfinished east wing of the main building was used by the U.S. Army as a general hospital for sick and wounded soldiers. The Army hospital officially took the name of St. Elizabeth's Army Medical Hospital to differentiate it from the psychiatric hospital in the west wing of the same building. The name St. Elizabeth's was derived from the colonial-era name for the tract of land on which the hospital was built.

| |

After the Civil War and the closing of the Army's hospital, the St. Elizabeths name was used unofficially and intermittently until 1916, when Congress passed legislation changing the name from the Government Hospital for the Insane to St. Elizabeths Hospital, inexplicably omitting the possessive apostrophe.[4] It also transferred hospital to the United States Department of Interior.

In the late 19th century the hospital temporarily housed animals that were brought back from expeditions for the Smithsonian Institution, because of lack of housing for the animals at the yet-to-be-built National Zoo.[9]

By 1940 St. Elizabeths Hospital was transferred to the Federal Security Agency, and after abolition of service the hospital was transferred to Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.[10] At its peak, the St. Elizabeths campus housed 8,000 patients and employed 4,000 people.[11] Beginning in the 1950s, however, large institutions such as St. Elizabeths were being criticized for hindering the treatment of patients. Community-based health care, as specified in the passage of the 1963 Community Mental Health Act, led to deinstitutionalization. The act provided for local outpatient facilities and drug therapy as a more effective means of allowing patients to live near-normal lives. The first community-based center for mental health was established at St. Elizabeths in 1969.[7] The patient population of St. Elizabeth's steadily declined.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the hospital was transferred to the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services.[10]

Later years

After several decades in decline, it was decided that the large campus could no longer be adequately maintained. In 1987, hospital functions on the eastern campus were transferred from the United States Department of Health and Human Services to the District of Columbia government by St. Elizabeths Hospital and District of Columbia Mental Health Services Act of 1984,[12] with the federal government retaining ownership of the western campus.[13]

East Campus

By 1996, only 850 patients remained at the hospital and years of neglect had become apparent; equipment and medicine shortages occurred frequently, and the heating system was broken for weeks at a time. By 2002, all remaining patients on the Federal western campus were transferred to other facilities.[11] Although it continues to operate, it does so on a far smaller scale than it once did. As of January 31, 2009, the current patient census was 404 in-patients.[14]

In recent years, approximately half of St. Elizabeths' patients are civilly committed to the hospital for treatment; the other half are forensic (criminal) patients.[15] Forensic patients are those who are adjudicated to be criminally insane (not guilty by reason of insanity) or considered incompetent to stand trial. Civil patients are those who are admitted owing to an acute need for psychiatric care. Civil patients can be voluntarily or involuntarily committed for treatment.

A new civil and forensic hospital was built on the East Campus by the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health and opened in the spring of 2010, housing approximately 297 patients. Until the new hospital opened, civil patients were cared for in various buildings on the East Campus; forensic patients were housed in the John Howard Pavilion. In the new facility, civil and forensic patients live in separate units of the same building. The new hospital also houses a library, an auditorium, multiple computer laboratories, and a small museum in the lobby.

In 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice and the District of Columbia reached a settlement over allegations that the civil rights of patients housed at St. Elizabeths were violated by the District.[16] On August 28, 2014, the Department of Justice found that St. Elizabeths had "significantly improved the care and treatment of persons confined to Saint Elizabeths Hospital" and asked a federal court to dismiss the injunction.[17] In January 2015, DC Auditors dismissed the settlement agreement and officially ended oversight of St. Elizabeths Hospital.[18]

The St. Elizabeths East Campus is a planned redevelopment for mixed use rental property development.[19][20][21] On September 22, 2018, St. Elizabeths East Entertainment and Sports Arena, home to the Washington Mystics and Capital City Go-Go, as well as the practice facility for the Washington Wizards opened on the campus.

West Campus

After the 1987 separation of the campuses, several commercial redevelopment opportunities were proposed by the D.C. government and consultants, including relocating the University of the District of Columbia to the campus or developing office and retail space. However, the tremendous cost of bringing the facilities up to code (estimated at $50–$100 million) kept developers away.[11]

With little interest in developing the site privately, the federal government stepped in. Control of the western campus—home of the oldest building on the campus, the Center Building—was transferred to the General Services Administration in 2004.[11] GSA improved security around the campus, shored up roofs, and covered the windows with plywood in an attempt to preserve the campus until a tenant could be found.

After three years of searching for an occupant, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced on March 20, 2007, that it would spend approximately $4.1 billion to move its headquarters and most of its Washington-based offices to a new 4,500,000-square-foot (420,000 m2) facility on the site, beginning with the United States Coast Guard in 2010.[22] DHS, whose operations are scattered around dozens of buildings in the Washington, D.C., area, hopes to consolidate at least 60 of its facilities at St. Elizabeths and to save $64 million per year in rental costs. DHS also hopes to improve employee morale and unity by having a central location from which to operate.[22]

The plans to locate DHS to St. Elizabeths have been met with criticism, however.[23] Historic preservationists argue that the move will destroy dozens of historic buildings located on the campus and that other alternatives should be considered.[11][24] Community activists have also expressed concern that the planned high-security facility will not interact with the surrounding community and do little to revitalize the economically depressed area.[11] In 2007 the District of Columbia reached a deal with the Department of Justice and agreed to fix widespread health and safety hazards in the hospital.[25]

A ceremonial groundbreaking for the DHS consolidated headquarters took place at St. Elizabeths on September 11, 2009. The event was attended by Senator Joseph Lieberman, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano, D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, DC Mayor Adrian Fenty, and acting GSA administrator Paul Prouty.[26]

The relocated U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters Building was forecast to open on May 2013,[27] and a ceremony was held on July 2013 at the site before it is to be officially opened.[28] Along U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters Building, several former hospital buildings (Atkins Hall, cafeteria) had been rehabilitated.[29]

By 2015, construction began in Center Building. Initially, this building has been slated for renovation, but internal structures (floors and ceilings) appeared to be beyond repair. Whole Center Building was rehabilitated by removing old internal structures and building new structures in the latter place, while retaining the historic facades.[30] Between March and April, 2019 Department's Headquarters components moved to Center Building.[31][32]

By April 2020, DHS National Operations Center relocated to the Mount Weather.[33]

Patients

Well-known patients of St. Elizabeths have included would-be presidential assassins Richard Lawrence (who attempted to kill Andrew Jackson) and John Hinckley Jr., who shot Ronald Reagan, as well as the assassin of James Garfield, Charles J. Guiteau (until his execution). Other notable residents were Mary Fuller, James Swann, Ezra Pound, and William Chester Minor.[11]

The poet Ezra Pound was kept in St. Elizabeths on the charge of treason for 13 years (1946–58). Despite his being sane, and proving it by the publication of two volumes of poetry and several translations, he was deemed unfit to stand trial by reason of insanity. In 1958 the treason charges were dropped, but Dr. Overholser discharged him as "incurably insane."

According to Kelly Patricia O'Meara, St. Elizabeths is believed to have treated over 125,000 patients, though an exact number is not known because of poor recordkeeping.[34] Additionally, she believes that thousands of patients are buried in unmarked graves across the campus, although records for the individuals buried in the graves have been lost. She believes that the incinerator on-site also brings up a few questions as to what may have happened to the bodies. The General Services Administration, current owner of the property, considered using ground penetrating radar to attempt to locate unmarked graves but has yet to do so.

More than 15,000 known autopsies were performed at St. Elizabeths from 1884 through 1982, and a collection of over 1,400 brains preserved in formaldehyde, 5,000 photographs of brains, and 100,000 slides of brain tissue was maintained by the hospital until the collection was transferred to a museum in 1986, according to O'Meara.[34] In addition to the mental health patients buried on the campus, several hundred American Civil War soldiers are interred at St. Elizabeths.[35]

Contributions to medicine

Several important therapeutic techniques were pioneered at St. Elizabeths, and it served as a model for later institutions.[11] Walter Freeman, onetime laboratory director, was inspired by St. Elizabeths to pioneer the transorbital lobotomy.[36] During American involvement in World War II, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, predecessor to the CIA) used facilities and staff at St. Elizabeths hospital to test "truth serums". OSS unsuccessfully tested a mescaline and scopolamine cocktail as a truth drug on two volunteers at St. Elizabeths Hospital. Separate tests of THC as a truth serum were equally unsuccessful.[37] In 1963 Dr. Luther D. Robinson, the first African American superintendent of St. Elizabeths, founded the mental health program for the deaf and was throughout his career a leading authority on treating deaf patients with brain disorders.[7]

Facilities and grounds

The campus of St. Elizabeths sits on bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers in the southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. It is divided by Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue between the 118-acre (48 ha) east campus (owned by the D.C. government) and the 182-acre (74 ha) west campus (owned by the federal government).[1] It has many important buildings, foremost among them the Center Building, designed according to the principles of the Kirkbride Plan by Thomas U. Walter (1804–87), who is better known as the primary architect of the expansion of the U.S. Capitol that was begun in 1851.[11]

Much of St. Elizabeths' campus has fallen into disuse and is in serious disrepair. It was named in 2002 one of the nation's 11 Most Endangered Places by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[24] Access to many areas of the campus, including the abandoned western campus (which houses the Center Building), is restricted.[13]

In popular culture

- The hospital was referred to in an episode of the television series Bonanza. The episode was "The Unseen Wound", featuring Leslie Nielsen as a sheriff, playing a former Civil War–era Army officer who falls victim to PTSD, although the modern term was not used in the script.[38]

- In the TV series The Rebel episode "Berserk", a PTSD victim was told by Nick Adams's character at the end of the show as he climbed aboard a stagecoach that he's "headed to a new hospital in Washington called St. Elizabeths."

- Portions of the west campus can be seen in the film A Few Good Men.[39]

- National Public Radio interns toured the east and west campuses, then shared their experiences, in 2010.[40]

- St. Elizabeths is referenced several times in W.E.B. Griffin's The Corps Series and Men at War as a place that the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) will confine people they consider a security risk for the duration of World War II.

- Abraham Lincoln mentioned St. Elizabeths to Mary Todd Lincoln in the novel Mrs. Lincoln's Dressmaker by Jennifer Chiaverini. It is shown to her because she cannot control her grief over the death of her son Willie.

- The TNT series The Alienist sees Dr Kriezler looking for information regarding a former patient while visiting St. Elizabeth's.

References

- District of Columbia Department of Mental Health. "About St. Elizabeths Hospital". Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "St. Elizabeths Hospital". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- Cauvin, Henri E. (April 23, 2010). "D.C. celebrates building opening at St. Elizabeths". The Washington Post.

- "History of St. Elizabeths - GSA Development of St. Elizabeths Campus". www.stelizabethsdevelopment.com. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- Markon, Jerry (May 20, 2014). "Planned Homeland Security headquarters, long-delayed and over budget, now in doubt. Washington Post, p B1, 20 May 2014". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- Lowe, Gail (2010). East of the river. Washington DC: Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution. p. 75.

- Otto, Thomas (May 2013). "St. Elizabeths: A History" (PDF). U.S. General Services Administration. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "National Zoological Park, Records". Record Unit 74. Smithsonian Institution Archives. 1887 1887-1966. Retrieved April 10, 2012. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Robert B. Matchette; et al. "Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- Holley, Joe (June 17, 2007). "Tussle Over St. Elizabeths". The Washington Post. p. C01. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- "H.R.6224 - Saint Elizabeths Hospital and District of Columbia Mental Health Services Act". Congress.gov. November 8, 1984. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- National Institutes of Health. "Historic Medical Sites in the Washington, D.C. Area – St. Elizabeths Hospital". Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- "Trend Analysis" (PDF). District of Columbia Dept. of Mental Health. December 31, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- "December 2008 – Trend Analysis – Hospital Statistics" (PDF). DC Department of Mental Health. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- See Settlement Agreement, available at DMH.dc.gov, Retrieved on 2009-03-04. Archived June 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Justice Department Asks Court to Dismiss Saint Elizabeths Hospital Case After Conditions Improved Under Consent Decree". August 28, 2014.

- "D.C. officially ends oversight of St. Elizabeth's" (PDF). www.bizjournals.com. 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- "The arena's just the start. Residential overhaul of St. Elizabeths East to begin this summer". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "St. Elizabeths East - Flaherty & Collins Properties". Flaherty & Collins Properties. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "St. Elizabeths East Campus | dmped". dmped.dc.gov. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Losey, Stephen (March 17, 2007). "Homeland Security plans move to hospital compound". Federal Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Moe, Richard (January 8, 2009). "A Disaster for St. Elizabeths". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- National Trust for Historic Preservation (2002). "List of America's most endangered historic places – St. Elizabeths". Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Cauvin, Henri E. (May 15, 2007). "U.S., D.C. Reach Deal on St. E's". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- Press release (September 9, 2009). "DHS and GSA Participate in Joint Groundbreaking Ceremony for Consolidated DHS Headquarters". Homeland Security. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "Wegmans, large corporations could fill vacant D.C. sites". WTOP. April 26, 2012.

- "Log In or Sign Up to View". www.facebook.com.

- Clapp, Jeannie (June 8, 2015). "Plan the Work, Then Work the Plan". Construction Magazine. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- "Historic Center Building Renovation - St. Elizabeths West Campus". 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- https://federalnewsnetwork.com/facilities-construction/2018/11/dhs-on-track-to-move-nielsen-to-substantially-complete-st-elizabeths-office/

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2019-07011.pdf

- http://archive.is/Uny7m#selection-2019.68-2019.81

- O'Meara, Kelly Patricia (August 6, 2001). "Forgotten Dead of St. Elizabeths". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/1043

- "PBS.org".

- "Erowid War Vault : Timeline". www.erowid.org.

- "The Unseen Wound".

- A Few Good Men (1992) – Filming Locations on IMDb

- "New Life For Our Oldest Federal Psychiatric Facility". May 3, 2010. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

Further reading

- Otto, Thomas. St. Elizabeths: A History. U.S. General Services Administration. 2013

- Streatfeild, D. Brainwash. St. Martin's Press. 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website

- St. Elizabeth's Hospital East Campus Redevelopment

- St. Elizabeth's Hospital Facebook Page

- Listing at the National Park Service

- Kirkbride Buildings

- GSA Development of St. Elizabeths Campus

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. DC-11, "St. Elizabeths Hospital West Campus"

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Saint Elizabeths Hospital