Spire

A spire is a tapering conical or pyramidal structure on the top of a building, often a skyscraper or a church tower, similar to a steep tented roof. Etymologically, the word is derived from the Old English word spir, meaning a sprout, shoot, or stalk of grass.[1]

General functions

Symbolically, spires have two functions. Traditionally, one has been to proclaim a martial power of religion. A spire, with its reminiscence of the spear point, gives the impression of strength. The second is to reach up toward the skies.[2] The celestial and hopeful gesture of the spire is one reason for its association with religious buildings. A spire on a church or cathedral is not just a symbol of piety, but is often seen as a symbol of the wealth and prestige of the order, or patron who commissioned the building.

As an architectural ornament, spires are most consistently found on Christian churches, where they replace the steeple. Although any denomination may choose to use a spire instead of a steeple, the lack of a cross on the structure is more common in Roman Catholic and other pre-Reformation churches. The battlements of cathedrals featured multiple spires in the Gothic style (in imitation of the secular military fortress).

Gothic and neo-Gothic spires

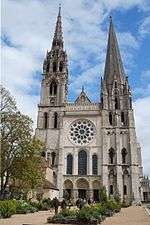

A spire declared the presence of the Gothic church at a distance and advertised its connection to heaven. The tall, slender pyramidal twelfth-century spire on the south tower Chartres Catedral is one of the earliest spires. Openwork spires were an astounding architectural innovation, beginning with the early fourteenth-century spire at Freiburg Minster, in which the pierced stonework was held together by iron cramps. The openwork spire, according to Robert Bork,[3] represents a "radical but logical extension of the Gothic tendency towards skeletal structure." The organic skeleton of Antoni Gaudi's phenomenal spires at the Sagrada Família in Barcelona represent an outgrowth of this Gothic tendency. Designed and begun by Gaudi in 1884, they were not completed until the 20th century.

In England, "spire" immediately brings to mind Salisbury Cathedral. Its 403-foot (123-m) spire, built between 1320 and 1380, is one of the tallest of the period anywhere in the world. A similar but slightly smaller spire was built at the Church of All Saints, Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire, England, which indicates the popularity of the spire spreading across the country during this period. We will never know the true popularity of the medieval spire, as many more collapsed within a few years of building than ever survived to be recorded. In the United Kingdom spires generally tend to be reserved for ecclesiastical building, with the exception to this rule being the spire at Burghley House, built for Elizabeth I's Lord Chancellor in 1585.

In the early Renaissance the spire was not restricted to the United Kingdom: the fashion spread across Europe. After the destruction of the 135 m tall spire of the St. Lambert's Cathedral, Liège in the 19th century, the 123 m spire of Antwerp is the tallest ecclesiastical structure in the Low Countries . Between 1221 and 1457 richly decorated open spires were built for the Burgos Cathedral in Spain while at Ulm Minster in Germany the 529-foot (161-m) spire built in the imported French Gothic style between 1377 and 1417 ultimately failed.[4]

The Italians never really embraced the spire as an architectural feature, preferring the classical styles. The Gothic style was a feature of Germanic northern Europe and was never to the Italian taste, and the few Gothic buildings in Italy always seem incongruous.

The blend of the classical styles with a spire occurred much later. In 1822, in London, John Nash built All Souls, Langham Place, a circular classical temple, with Ionic columns surmounted by a spire supported by Corinthian columns. Whether this is a happy marriage of styles or a rough admixture is a question of individual taste.

During the 19th century, the Gothic Revival architecture knew no bounds. With advances in technology, steel production, and building techniques the spire enjoyed an unprecedented surge through architecture, Cologne Cathedral's famous spires, designed centuries earlier, were finally completed in this era.

Spires have never really fallen out of fashion. In the twentieth century reinforced concrete offered new possibilities for openwork spires.

Burgos Cathedral

Burgos Cathedral

Basilica Sagrada Família in Barcelona

Basilica Sagrada Família in Barcelona

The Gothic spire of Ulm Minster

The Gothic spire of Ulm Minster The spire of Salisbury Cathedral, at 123 metres tall the tallest in the UK

The spire of Salisbury Cathedral, at 123 metres tall the tallest in the UK.jpg) The Gothic spire of Antwerp Cathedral

The Gothic spire of Antwerp Cathedral

Traditional types of spires

- Conical stone spires: These are usually found on circular towers and turrets, usually of small diameter.

- Masonry spires: These are found on medieval and revival churches and cathedrals, generally with towers that are square in plan. While masonry spires on a tower of small plan may be pyramidal, spires on towers of large plan are generally octagonal. The spire is supported on stone squinches which span the corners of the tower, making an octagonal plan. The spire of Salisbury Cathedral is of this type and is the tallest masonry spire in the world, remaining substantially intact since the 13th century. Other spires of this sort include the south spire of Chartres Cathedral, and the spires of Norwich Cathedral, Chichester Cathedral and Oxford Cathedral.

- Openwork spires: These spires are constructed of a network of stone tracery, which, being considerably lighter than a masonry spire, can be built to greater heights. Many famous tall spires are of this type, including the spires of Ulm Minster (the world's tallest church), Freiburg Minster, Strasbourg Cathedral, Vienna Cathedral, Prague Cathedral, Burgos Cathedral and the twin spires of Cologne Cathedral.

- Complex spires: These are stone spires that combine both masonry and openwork elements. Some such spires were constructed in the Gothic style, such as the north spire of Chartres Cathedral. They became increasingly common in Baroque architecture, and are a feature of Christopher Wren's churches.

- Clad spires: These are constructed with a wooden frame, often standing on a tower of brick or stone construction, but also occurring on wooden towers in countries where wooden buildings are prevalent. They are often clad in metal, such as copper or lead. They may also be tiled or shingled.

- Clad spires can take a variety of shapes. These include:

- Pyramidal spires, which may be of low profile, rising to a height not much greater than its width, or, more rarely, of high profile.

- Rhenish helm: This is a four-sided tower topped with a pyramidal roof. each of the four sides of the roof is rhomboid in form, with the long diagonal running from the apex of roof to one of the corners of the supporting tower; each side of the tower is thus topped with a gable from whose peak a ridge runs to the apex of the roof.

- Broach spires: These are octagonal spires sitting on a square tower, with a sections of spire rising from each corner of the tower, and bridging the spaces between the corners and four of the sides.

- Bell-shaped spires: These spires, sometimes square in plan, occur mostly in Northern, Alpine and Eastern Europe, where they occur alternately with onion-shaped domes.

References

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- Robert Odell Bork, Great Spires: Skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem, 2003, explores the complex layering of religious and political significance in spires.

- Robert Bork, "Into Thin Air: France, Germany, and the Invention of the Openwork Spire" The Art Bulletin 85.1 (March 2003, pp. 25-53), p 25.

- The present spire at Ulm is neo-Gothic.