Shona people

The Shona (/ˈʃoʊnə/) are a Bantu ethnic group native to Southern Africa, primarily the country of Zimbabwe where they form a vast majority. The people are divided into five major clans and adjacent to other groups of very similar culture and languages.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 12 million (2000)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11 million (2000)[1] | |

| 173,000[2][3] | |

| 30,200[4][5] | |

| Languages | |

| Shona | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, traditional Shona religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lemba, Kalanga, Venda and other Bantu peoples | |

| MunhumutapaMashonaland | |

|---|---|

| Person | muShona |

| People | vaShona |

| Language | chiShona |

| Country | varozvi |

Shona regional classification

The Shona people are divided into various tribes in the east and north regions of Zimbabwe. It is important not to mistake the Kalanga tribe of Matabeleland as one of the various tribes, as these are a distinct clan of the Lozwi-Moyo Empire. Ethnologue notes that the language of the Bakalanga is mutually intelligible with the main dialects of Karanga as well as other Bantu languages in central and east of Africa, but counts them separately. The Kalanga and Karanga are believed to be one clan who built the Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe, Khami, etc. but the Karanga were assimilated by the Zezuru. Many Karanga and Kalanga words are interchangeable but Kalanga is distinctly different from Zezuru.

- Sure members (10.7 million):[6]

- Karanga or Southern Shona (about 4.5 million)

- Duma

- Njiva (mrewa)

- Jena

- Mhari (Mari)

- Ngova

- Nyubi

- Govera

- Zezuru or Central Shona (3.2 million people)

- Budya

- Gova

- Tande

- Tavara

- Nyongwe

- Pfunde

- Shangwe

- Korekore or Northern Shona (1.7 million people)

- Shawasha

- Gova

- Mbire

- Tsunga

- Kachikwakwa

- Harava

- Nohwe

- Njanja

- Nobvu

- Kwazvimba (Zimba)

- narrow Shona

- Toko

- Hwesa

- Karanga or Southern Shona (about 4.5 million)

- Members or close relatives:

- Manyika or Eastern Shona (1.2 million)[7] in Zimbabwe (861,000) and Mozambique (173,000). In Desmond Dale's basic Shona dictionary, also special vocabulary of Manyika dialect is included.[8]

- Ndau[9] in Mozambique (1,580,000) and Zimbabwe (800,000). Their language is only partly intelligible with the main Shona dialects and comprises some click sounds that do not occur in standard ChiShona.

Language and identity

When the term Shona was invented during the Mfecane in late 19th century, possibly by the Ndebele king Mzilikazi, it was a pejorative for non-Nguni people. On one hand, it is claimed that there was no consciousness of a common identity among the tribes and peoples now forming the Shona of today. On the other hand, the Shona people of Zimbabwe highland always had in common a vivid memory of the ancient kingdoms, often identified with the Monomotapa state. The terms "Karanga"/"Kalanga"/"Kalaka", now the names of special groups, seem to have been used for all Shona before the Mfecane.[10]

Dialect groups are important in Shona although there are huge similarities among the dialects. Although 'standard' Shona is spoken throughout Zimbabwe, the dialects not only help to identify which town or village a person is from (e.g. a person who is Manyika would be from Eastern Zimbabwe, i.e. towns like Mutare) but also the ethnic group with which the person identifies. Each Shona dialect is specific to a certain ethnic group, i.e. if a woman speaks the Manyika dialect from the Manyika group/tribe, she observes certain customs and norms specific to her group. As such, if one is Zezuru, he speaks the Zezuru dialect and observes those customs and beliefs that are specific to that group.

In 1931, during the process of trying to reconcile the dialects into the single standard Shona, Professor Clement Doke[11] identified six groups, each with subdivisions:

- The Korekore or Northern Shona, including Taυara, Shangwe, Korekore proper, Goυa, Budya, the Korekore of Urungwe, the Korekore of Sipolilo, Tande, Nyongwe of "Darwin", Pfungwe of Mrewa;

- The Zezuru group, including Shawasha, Haraυa, another Goυa, Nohwe, Hera, Njanja, Mbire, Nobvu, Vakwachikwakwa, Vakwazvimba, Tsunga;

- The Karanga group, including Duma, Jena, Mari, Goυera, Nogoυa, Nyubi;

- The Manyika group, including Hungwe, Manyika themselves, Teυe, Unyama, Karombe, Nyamuka, Bunji, Domba, Nyatwe, Guta, Bvumba, Here, Jindwi, Boca;

- The Ndau group (mostly Mozambique), including Ndau themselves, Garwe, Danda, Shanga.

The above differences in dialects developed during the dispersion of tribes across the country over a long period of time. The influx of immigrants into the country from bordering countries has obviously contributed to the variety.

Shona culture

There are more than ten million people who speak a range of related dialects whose standardized form is also known as Shona.

Subsistence

The Shona are traditionally agricultural. Their crops are sorghum (in modern age replaced by maize), yam, beans, bananas (since middle of the first millennium), African groundnuts, and beginning in the 16th century, pumpkins. Sorghum and maize are used to prepare the main dish, a thickened porridge called sadza, and the traditional beer, called hwahwa.[12] The Shona also keep cattle and goats. The livestock had a special importance as a food reserve in times of drought.[13]

The precolonial Shona states received a great deal of their revenues from the export of mining products, especially gold and copper.[13]

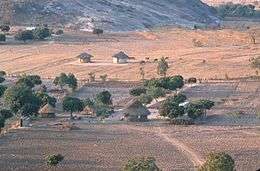

Housing

In their traditional homes, called musha, they had (and have) separate round huts for the special functions, such as kitchen and lounging around a yard (ruvanze) cleared from ground vegetation.[14]

Arts

Sculpture

The Shona are known for the high quality of their stone sculptures, which were originally discovered in the 1940s and began to gain popularity more recently. The building of these sculptures started in the eleventh century, was popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and began to decline during the centuries thereafter. Most of these sculptures are made using sedimentary stone such as soap stone to carve figures of birds or humans; however some are made using harder forms of stone including serpentine and even rare forms like verdite. These sculptures are essentially a combination of African folk stories and European influence. In the 1950s, artists in Zimbabwe began carving stone sculptures for the purpose of selling them to European art lovers. These sculptures quickly gained popularity and were shown and bought by art museums all over the world. Many of these sculptures show transformations of spirits into animals or animals into spirits. However some are abstract and use only shape in a pleasing or interesting way. Despite these works being called "Shona sculpture" many of the artists are actually from neighboring countries and sculpture made from stone has become a source of national pride in Zimbabwe. Many artists in Zimbabwe also make a living by carving wood and stone to sell to tourists. There also exists a pottery tradition.

Garments

Traditional textile production was expensive and of high quality. People preferred to wear skins or imported tissues.[13]

Music

Shona traditional music, in contrast to European tradition but embedded in other African traditions, tends to have constant melodies and variable rhythms. The most important instruments in this music are the drum(Ngoma) and the mbira. The drums that are played within Shona music vary in size and shape depending on the genre of music they are accompanying. The way in which these drums are played depends on both the size of the drum and the type of music. Typically, large drums are played with sticks while smaller drums are played using an open palm; however, the small drum that is used during Ambhiza is played using both a hand and a stick. This stick is used to rub or scratch the drum to produce a screeching sound.

The mbira is the most famous Zimbabwean instrument and has its own varitions., including the nhare (telephone), Mbira Dzavadzimu (ancestors mbira,) and the nyunga-nyunga mbira. The mbira is played during both religious and secular gatherings, and the different types of mbira have different purposes. The Dzavadzimu mbira has between 22 and 24 keys and is used for invoking the spirits, while the Nyunga-Nyunga mbira only has 15 keys and has become popular in the education sector of Zimbabwe where it is taught from primary school all the way up to the university level. Along with the varying classifications of Mbira, the Shona people also have a variation of names for this instrument including njari, matepe, mbira dzavandau, karimba, nyunganyunga, matepe, madebe dza mhondoro and hero.

The music of the Shona people also utilizes many other percussion instruments such as shakers (hosho), leg rattles (magaga,magalau & amahlayi), and wooden clappers (makwa). Other percussion instruments that are used by the Shona people include the chikorodzi which is a notched stick that is played using another stick, and the kanyemba which is made by attaching many bamboo strips and filling them up with small seeds.

Religion

The main goal of the Shona religious practice is balance between mankind and the environment. This is achieved by living lives that are respectful of one another and the ancestors. An important part of this practice is a rain ceremony that is practiced by every sub-group of Shona culture.In this ceremony, the Shona people brew a beer in order to pay respect to their ancestors who will communicate with the high god Mwari in order to bring rain, fertility, and protection from illness to the people. However, in order for their ancestral spirits to communicate with the Mwari, they most follow a moral code. This code forbids incest, murder, eating the meat of their totem animal (Mutupo), and the killing of any of four different types of snakes. If this moral code is followed, then the ancestor will ask that the high god reward them. However, if it is not, then the people may experience drought, illness, infertility, and death in the family.The beer that is brewed for the ancestors using life sustaining ziviyo (finger millet/rapoko) is a symbol of life that is offered in order to ensure sustenance of life will be received. This rain ceremony is held annually before crops are planted and takes place at a tree shrine.This shrine goes by multiple names, dependent on the region. In the central and northern region of Shona territory, the shrine is called rushanga. The Shona people living in the southern region refer to their tree shrine as muturo (place of sacrifice).

Gods

The Shona religious spirits can be organized in a hierarchal manner. Some of these gods are referred to using multiple names and each of them has a specific purpose which is outlined below.

Mwari:

The high god and creator. Also referred to as Nyadenga (Lord of the sky), Musikavanhu (creator of the people), Matangakugara (the first of all beings), Chikara (one who inspires awe), Zame (great spirit), Mbedzi (giver of life/one who gives seed), and Mbereka (He who gives life/birth). Sometimes referred to as Ambuya (Grandmother/woman who has had many children) because Mwari is viewed as the origin of fertility.

Gombwe Remvura/Makombe:

Rain spirits: Snake Totem, children of Mwari who give rain and heal the people.

Mhondoro:

Clan spirits, attached to chieftaincy: guardians of the region who foretell the future, intercede for rain and heal the people. Also referred to as lion spirits.

Mudzimu/Vadzimu:

Family spirits who protect, counsel and heal the Shona people.

This hierarchy also includes the njuzu and jukiwa which are in charge of healing specifically, the shave(foreign), the Ngozi who handle retribution, and the muroyi who are witch and sorcerer spirits.

Transition (living to ancestral)

The transition from a person who is living (Munhu) to that of an ancestral spirit or mudzimu happens throughout the year after a person's death. During this time, the spirit is thought to wander and adjust to its new identity before being called back into the circle of the family and becoming a mudzimu. When a person dies and begins their life as a spirit, they are called mweya (air, breath, soul, spirit) and their death is seen as a second birth because the mweya will be on a journey that is completed when it becomes an ancestral spirit or mudzimu. In order for this spirit to become a mudzimu a special ceremony called kurova guva is held exactly one year after the person's death.

Mediums and communication

Once a spirit becomes a mudzimu, it chooses someone from its family to be its medium and communicate with the rest of the Shona people. Among the Mhebre Dandanda these spirits "come out" to speak in one of three ways. As vadzimu who are male (sekuru) spirits that tend to choose female mediums slightly more often than male mediums or as female spirits which tend to "come out" more often as n'angas (healers) or njuzu (healing water spirit).

During the rain ceremony of the Mhebre Dandanda there are thirteen dancers who host the vadzimu spirits, and one of the drummers hosts a final spirit. This spirit is more powerful and sent as a guardian to the other spirits. This is a gombwe revura spirit who the mhebre Dandanda call Chinovaranga and is considered as either a spirit who never was a person or a spirit of the original ancestors.

There is another spirit thought to be present during these ceremonies, a spirit known as makobwe (snake spirits) who are thought to be closest to Mwari and therefore the most powerful of the spirits below Him. The people believe they have the ability to heal using only snuff and water as well as the ability to intercede for rain. These spirits are said to be called upon by the mhondoro or clan spirits to ensure the rain will come.

.jpg)

The term Shona is as recent as the 1920s.

Kingdoms

The Karanga, from the 11th century, created empires and states on the Zimbabwe plateau. These states include the Great Zimbabwe state (12th-16th century), the Torwa state, and the Munhumutapa states, which succeeded the Great Zimbabwe state as well as the Rozwi state, which succeeded the Torwa state, and with the Mutapa state existed into the 19th century. The states were based on kingship with certain dynasties being royals.

The major dynasties were the Rozwi of the Moyo (Heart) Totem, the Nzou of the Mwenemutapa (Elephant), and the Hungwe (Fish Eagle) dynasties that ruled from Great Zimbabwe. The Karanga who speak Chikaranga are related to the Kalanga possibly through common ancestry, however this is still debatable. These groups had an adelphic succession system (brother succeeds brother) and this after a long time caused a number of civil wars which, after the 16th century, was taken advantage of by the Portuguese. Underneath the king were a number of chiefs who had sub-chiefs and headmen under them.[13]

Decay

The kingdoms were destroyed by new groups moving onto the plateau. The Ndebele destroyed the Chaangamire's Rowzi state in the 1830s, and the Portuguese slowly eroded the Mutapa state, which had extended to the coast of Mozambique after the state's success in providing valued exports for the Swahili, Arab and East Asian traders, especially in the mining of gold, known by the pre-colonization miners as kuchera dyutswa. The British destroyed traditional power in 1890 and colonized the plateau of Rhodesia. In Mozambique, the Portuguese colonial government fought the remnants of the Mutapa state until 1902.[13]

Beliefs

Nowadays, between 60% and 80% of the Shona are Christians. Besides that, traditional beliefs are very vivid among them. The most important features are ancestor-worship (the term is called inappropriate by some authors) and totemism.

Ancestors

According to Shona tradition, the afterlife does not happen in another world like Christian heaven and hell, but as another form of existence in the world here and now. The Shona attitude towards dead ancestors is very similar to that towards living parents and grandparents.[15]

Nevertheless, there is a famous ritual to contact the dead ancestors. It is called Bira ceremony and often lasts all night.

The Shona believe in heaven and have always believed in it. They do not talk about it because they do not know what is there so there is no point. When people die, they either go to heaven or they do not. What is seen as ancestor worship is nothing of the sort. When a person died, God (Mwari) was petitioned to tell his people if he was now with Him. They would go into a valley surrounded by mountains on a day when the wind was still.

An offering would be made to Mwari and wood reserved for such occasions would be burnt. If the smoke from the fire went up to heaven, the person was with Mwari; if it dissipated, the deceased was not. If he was with Mwari then he would be seen as the new intercessor to Him. There were always three intercessors, so the Shona prayed somewhat along these lines:

To our grandfather, Tichivara, we ask that you pass on our message to our great-grandfather, Madzingamhepo, so he can pass it on to our great-great-grandfather, Mhizhahuru, who will in turn pass it to the creator of all, the bringer of rain, the master of all we see, He who sees to our days, the ancient one (these are just examples of the meanings of the names of God. To show respect to Him, the Shona listed about thirty or so of his names starting with the most common and getting to the more complex and or ambiguous ones like... Nyadenga- the heaven who dwells in heaven, Samatenga- the heavens who dwells in the heavens, our father... Then they would describe what they needed.

His true name, Mwari, was too sacred to be spoken in everyday occasions and was reserved for high ceremonies and the direst of need as it showed Him disrespect to be free with it. As a result, God had many names, all of which would be recognised as His even by people who had never heard the name before. He was considered too holy to contact directly, hence the need for ancestral intercessors. Each new intercessor replaced the oldest of the three.

When the missionaries came, they talked about Jesus being the universal intercessor, which made sense as there were conflicts in the society, with some people wanting their so-and-so, who they believed was with God, to be included in intercession. Doing away with ancestral intercessors made sense.

However they made no effort to know how the Shona prayed and violently insisted they drop the other gods (i.e., the different names for God) and keep the high name Mwari. To the Shona this sounded like 'to get to God all you need to do is disrespect him in the most profound way', as leaving out his names in prayer was the highest form of disrespect.

The missionaries would not drink water from the Shona, the first form of hospitality required in the tribe. They would not eat the same food as the Shona, another thing God encouraged.

Added to that, Matopos hill and the land around it was considered the most fertile land in Mashonaland and was reserved for God. John Rhodes took that land as his and chased away the caretakers of the land. People could no longer go there to petition God.

All of which led people to hold on to ancestral intercessors all the more. Jesus was seen as a universal intercessor but as his messengers lacked 'proper manners', it reinforced ancestral intercessors.

The modern form devolved from the original as most ceremonies for God were outlawed, and families were displaced and separated. The only thing left was to hold on to their ancestors. Still, if you ask the so-called ancestor "worshippers" about their religion, they would tell you that they are Christians.

Totems

In Zimbabwe, totems (mutupo) have been in use among the Shona people since the initial development of their culture. Totems identify the different clans among the Shona that historically made up the dynasties of their ancient civilization. Today, up to 25 different totems can be identified among the Shona, and similar totems exist among other South African groups, such as the Tswana, Zulu, the Ndebele, and the Herero.[16]

People of the same clan use a common set of totems. Totems are usually animals and body parts. Examples of animal totems include Shato/Mheta (Python), Shiri/Hungwe (Fish Eagle), Mhofu/Mhofu Yemukono/Musiyamwa (Eland), Mbizi/Tembo (Zebra),Mukanya/Gudo(Baboon), Shumba (Lion), Mbeva/Hwesa/Katerere (Mouse), Soko (Monkey), Nzou (Elephant), Ngwena (crocodile), and Dziva (Hippo). Examples of body part totems include Gumbo (leg), Moyo (heart), and Bepe (lung). These were further broken down into gender related names. For example, Zebra group would break into Madhuve for the females and Dhuve or Mazvimbakupa for the males. People of the same totem are the descendants of one common ancestor (the founder of that totem) and thus are not allowed to marry or have an intimate relationship. The totems cross regional groupings and therefore provide a wall for development of ethnicism among the Shona groups.

Shona chiefs are required to be able to recite the history of their totem group right from the initial founder before they can be sworn in as chiefs.

Orphans

The totem system is a severe problem for many orphans, especially for abandoned babies.[17] People are afraid of being punished by ghosts, if they violate rules connected with the unknown totem of a foundling. Therefore, it is very difficult to find adoptive parents for such children. And if the foundlings have grown up, they have problems getting married.[18]

Burials

The identification by totem has very important ramifications at traditional ceremonies such as the burial ceremony. A person with a different totem cannot initiate burial of the deceased. A person of the same totem, even when coming from a different tribe, can initiate burial of the deceased. For example, a Ndebele of the Mpofu totem can initiate burial of a Shona of the Mhofu totem and that is perfectly acceptable in Shona tradition. But a Shona of a different totem cannot perform the ritual functions required to initiate burial of the deceased.

If a person initiates the burial of a person of a different totem, he runs the risk of paying a fine to the family of the deceased. Such fines traditionally were paid with cattle or goats but nowadays substantial amounts of money can be asked for. If they bury their dead family members, they would come back at some point to cleanse the stone of the burial. if someone bets his or her parents he would suffer after death of the parents due to their spirit.

Notable Shona People

- Constantino Chiwenga

- Chartwell Dutiro

- Emmerson Mnangagwa

- Oliver Mtukudzi

- Robert Mugabe

- Shingai Shoniwa (of music band Noisettes)

- Morgan Tsvangirai

See also

References

- Ehnologue: Languages of Zimbabwe Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, citing Chebanne, Andy and Nthapelelang, Moemedi. 2000. The socio-linguistic survey of the Eastern Khoe in the Boteti and Makgadikgadi Pans areas of Botswana.

- "Ethnologue: Languages of Mozambique". Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- "Ethnologue: Languages of Botswana". Archived from the original on 2013-09-29. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- "Ethnologue: Languages of Zambia". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- Joshua project: South Africa

- Ehnologue: Shona

- Ethnologue: Manyika

- Ethnologue: Ndau

- Zimbabwes rich totem strong families – a euphemistic view on the totem system Archived 2015-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Doke, Clement M.,A Comparative Study in Shona Phonetics. 1931. University of Witwatersrand Press, Johannesburg.

- Correct spelling according to D. Dale, A basic English Shona Dictionary, mambo Press, Gwelo (Gweru) 1981; some sources write "whawha", misled by conventions of English words like "what".

- David N. Beach: The Shona and Zimbabwe 900–1850. Heinemann, London 1980 und Mambo Press, Gwelo 1980, ISBN 0-435-94505-X.

- Friedrich Du Toit, Musha: the Shona concept of home, Zimbabwe Pub. House, 1982

- Michael Gelfand, The spiritual beliefs of the Shona, Mambo Press 1982, ISBN 0-86922-077-2, with a preface by Referent Father M. Hannan.

- Totem Author: Magelah Peter - Published: May 21, 2007, 4:56 am

- "Baby dumping in Zimbabwe". Archived from the original on 2015-05-28. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- Orphan for Life

Further reading

- “Arts and Culture in the ‘Royal Residence.’” Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, Oct. 2018, pp. 141–149. EBSCOhost 133158724.

- McEwen, Frank. “Shona Art Today.” African Arts, vol. 5, no. 4, 1972, pp. 8–11. JSTOR 3334584.

- Van Wyk, Gary; Johnson, Robert (1997). Shona. New York: Rosen Pub Group. ISBN 9780823920112.

- Zilberg, Jonathan L. Zimbabwean Stone Sculpture: The Invention of a Shona Tradition, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Ann Arbor, 1996 ProQuest 304300839.