Sentinelese

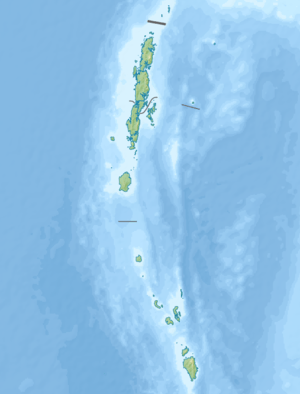

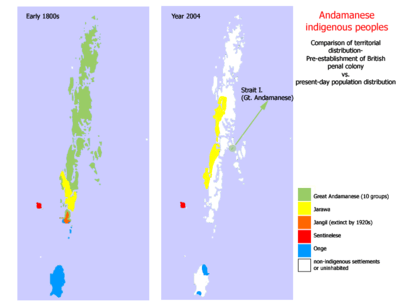

The Sentinelese, also known as the Sentineli and the North Sentinel Islanders, are an indigenous people who inhabit North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal in India. Designated a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group and a Scheduled Tribe, they belong to the broader class of Andamanese people.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 50–200 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North Sentinel Island | |

| Languages | |

| Sentinelese (presumed) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Possibly Jarawa or Onge | |

North Sentinel Island North Sentinel Island (India)  North Sentinel Island North Sentinel Island (Andaman and Nicobar Islands) |

Along with the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas, the Onge, the Shompen, and the Nicobarese, the Sentinelese are one of the six native and often reclusive peoples of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Unlike the others, the Sentinelese appear to have consistently refused any interaction with the outside world. They are hostile to outsiders and have killed people who approached or landed on the island.[1]

In 1956, the Government of India declared North Sentinel Island a tribal reserve and prohibited travel within 3 miles (4.8 km) of it. It further maintains a constant armed patrol to prevent intrusions by outsiders. Photography is prohibited.

There is significant uncertainty as to the group's size, with estimates ranging between 15 and 500 individuals, but mostly between 50 and 200.

Overview

Geography

The Sentinelese live on North Sentinel Island in the Andaman Islands, which are in the Bay of Bengal and administered by India.[2][3] The island lies off the southwest coast of South Andaman Island, about 64 km (40 mi) west of Andaman capital Port Blair.[4] It has an area of about 59.67 km2 (23.04 sq mi) and a roughly square outline.[5][4] The seashore is about 50 yd (46 m) wide, bordered by a littoral forest that gives way to a dense tropical evergreen forest.[4] The island is surrounded by coral reefs and has a tropical climate.[4] The Onge call North Sentinel Island Chia daaKwokweyeh.[6]

Appearance

.jpg)

One report by Heinrich Harrer described a man as 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in) tall, possibly because of insular dwarfism (the so-called "Island Effect"), nutrition, or simply genetic heritage.[7] During a 2014 circumnavigation of their island, researchers put their height between 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) and 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) and recorded their skin colour as "dark, shining black" with well-aligned teeth. They showed no signs of obesity and had very prominent muscles.

Population

No rigorous census has been conducted[4] and the population has been variously estimated to be as low as 15 or as high as 500. Most estimates lie between 50 and 200.[8][9][3][10] A handbook released in 2016 by the Anthropological Survey of India on Vulnerable Tribe Groups estimates the population at between 100 and 150.[4]

The 1971 census estimated the population at around 82; the 1981 census at 100.[4] A 1986 expedition recorded the highest count, 98.[4] In 2001, the Census of India officially recorded 21 men and 18 women.[11] This survey was conducted from a distance and may not have been accurate.[12] 2004 post-tsunami expeditions recorded counts of 32 and 13 individuals in 2004 and 2005 respectively.[4] The 2011 Census of India recorded 12 males and three females.[13][14] During a 2014 circumnavigation researchers recorded six females, seven males (all apparently under 40 years old) and three children younger than four.

Practices

The Sentinelese are hunter-gatherers. They likely use bows and arrows to hunt terrestrial wildlife and more rudimentary methods to catch local seafood, such as mud crabs and molluscan shells. They are believed to eat a lot of molluscs, given the abundance of roasted shells found in their settlements.[4] Some of their practices have not evolved beyond those of the Stone Age; they are not known to engage in agriculture.[15][16][17] It is unclear whether they have any knowledge of making fire though investigations have shown they use fire.[18]

Similarities as well as dissimilarities have been spotted with the Onge people. They prepare their food similarly.[19] They share common traits in body decoration and material culture.[6] There are also similarities in the design of their canoes. (Of all the Andamanese tribes, only the Sentinelese and Onge make canoes.)[6] The Onge call them "Chanku-ate".[4] Similarities with the Jarawas have been also noted. Their bows have similar patterns; no such marks are found on Onge bows. Finally, both tribes sleep on the ground, while the Onge sleep on raised platforms.[20] The metal arrowheads and adze blades are quite large and heavier than those of other Andamanese tribes.[21]

The Sentinelese reside in small temporary huts erected on four poles with slanted leaf-covered roofs. They recognise the value of metal, having scavenged it to create tools and weapons and accepted aluminum cookware left by the National Geographic Society in 1974.[8] They have also developed canoes suitable for lagoon-fishing but use long poles rather than paddles or oars to propel them.[4][22] They seldom use the canoes for cross-island navigation.[22] Both genders wear bark strings; the men always tuck daggers into their waist belts.[4] They also wear some ornaments such as necklaces and headbands, but are essentially naked.[18][23][24] The wearing of jawbones of deceased relatives has been reported.[18] Artistic engravings of simple geometric designs and shade contrasts have been seen on their weapons.[4] The women have been seen to dance by slapping both palms on the thighs whilst simultaneously tapping the feet rhythmically in a bent-knee stance.[4]

Language

Because of their complete isolation, nearly nothing is known about the Sentinelese language, which is therefore unclassified.[25][26][27] It has been recorded that the Jarawa language is mutually unintelligible with the Sentinelese language.[25][11] There is uncertainty as to the range of overlap with the Onge language, if any.[28] The Anthropological Survey of India's 2016 handbook on Vulnerable Tribe Groups considers them mutually unintelligible.[4]

Age

The Sentinelese have been widely described as a Stone Age tribe, with some reports claiming they have lived in isolation for over 60,000 years. But Pandya speculates that the Sentinelese arose either from a deliberate, more recent migration or from drifting off the Little Andaman.

Isolation and uncontacted status

They are a community of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. Designated a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group[29] and a Scheduled Tribe,[30] they belong to the broader class of Andamanese people.

Along with the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas, the Onge, the Shompen, and the Nicobarese, the Sentinelese are one of the six native and often reclusive peoples of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[29] Unlike the others, the Sentinelese appear to have consistently refused any interaction with the outside world. They are hostile to outsiders and have killed people who approached or landed on the island.[31][32]

The first peaceful contact with the Sentinelese was made by Triloknath Pandit, a director of the Anthropological Survey of India, and his colleagues on 4 January 1991.[33]:288:289[34] Indian visits to the island ceased in 1997.[35]

Contact

First recorded sighting (1771)

In 1771, an East India Company hydrographic survey vessel, the Diligent, observed "a multitude of lights ... upon the shore" of North Sentinel Island, which is the island's first recorded mention. The crew did not investigate.[18]

First recorded contact (1867)

During the late summer monsoon of 1867, the Indian merchant-vessel Nineveh foundered on the reef off North Sentinel. All the passengers and crew reached the beach safely, but as they proceeded for their breakfast on the third day, they were subject to a sudden assault by a group of naked, short-haired, red-painted islanders with arrows that were probably iron-tipped.[18]

The captain, who fled in the ship's boat, was found days later by a brig and the Royal Navy sent a rescue party to the island. Upon arrival, the party discovered that the survivors had managed to repel the attackers with sticks and stones and that they had not reappeared.[18]

Andamanese scholar Vishvajit Pandya notes that Onge narratives often recall voyages by their ancestors to North Sentinel to procure metal.[36]

Colonial period

The first recorded visit to the island by a colonial officer was by Jeremiah Homfray in 1867. He recorded seeing naked islanders catching fish with bows and arrows, and was informed by the Great Andamanese that they were Jarawas.[37][38][27]

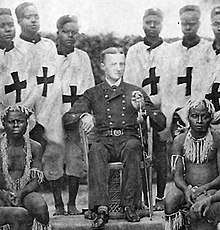

In 1880, in an effort to establish contact with the Sentinelese, British naval officer Maurice Vidal Portman, who was serving as a colonial administrator to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, led an armed group of Europeans along with convict-orderlies and Andamanese trackers (whom they had already befriended) to North Sentinel Island. On their arrival, the islanders fled into the treeline. After several days of futile search, during which they found abandoned villages and paths, Portman's men captured six individuals, an elderly man and woman and four children.[39] The man and woman died shortly after their arrival in Port Blair and the children sickened. Portman hurriedly sent the children back to the North Sentinel Island with ample gifts to establish friendly contact and noted their "peculiarly idiotic expression of countenance, and manner of behaving".[18]

Portman visited the island again in 1883,[27] 1885 and 1887.[38]

In 1896, a convict escaped from the penal colony on Great Andaman Island on a makeshift raft and drifted across to the North Sentinel beach. His body was discovered by a search party some days later with several arrow-piercings and a cut throat. The party did not see any islanders.[18]

In an 1899 speech, Richard Carnac Temple, who served as chief commissioner of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands from 1895 to 1904, reported that he had toured North Sentinel island to capture fugitives, but upon landing discovered that they had been killed by the inhabitants, who retreated in haste upon seeing his party approach.[40]

Temple also recorded a case where a Sentinelese apparently drifted off to the Onge and fraternized with them over the course of two years. When Temple and Portman accompanied him to the tribe and attempted to establish friendly contact, they did not recognize the individual and responded aggressively by shooting arrows at the group. The man refused to remain on the island.[40] Portman cast doubt on the exact time span the Sentinelese spent with the Onge, and believed that he had probably been raised by the Onge since childhood.[27]

Temple went on to describe the Sentinelese as "a tribe which slays every stranger, however inoffensive, on sight, whether a forgotten member of itself, of another Andamanese tribe, or a complete foreigner".[40]

MCC Bonnington, a British official, visited the island on two separate occasions in 1911 and 1932 to conduct a census. On the first occasion, he came across eight men on the beach and another five in two canoes, who retreated into the forest. The party progressed some miles into the island without facing any hostile response and saw a few huts with slanted roofs.[41] Notably, the Sentinelese were counted as a standalone group, for the first time, in the 1911 census.[20]

There have been other recorded instances of British administrators visiting the island, including Rogers in 1902, but none of the expeditions after 1880 had any ethnographic purpose, probably because of the island's small size and unfavorable location.[18]

In 1954, Italian explorer Lidio Cipriani visited the island but did not come across any inhabitants.[42]

Shipwrecks

In 1977, MV Rusley ran aground on the North Sentinel Reefs."North Sentinel Island, India: The Last Island You'll Ever Visit".

On 2 August 1981, the cargo ship Primrose, carrying cargo between Australia and Bangladesh, ran aground in rough seas just off North Sentinel Island, stranding a small crew.[43] After a few days, the captain dispatched a distress call asking for a drop of firearms and reported boats being prepared by more than 50 armed islanders intending to invade the ship. Strong waves prevented the Sentinelese canoes from reaching the ship and deflected their arrows. Nearly a week later, the crew were evacuated by a civilian helicopter contracted to the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) with support from Indian Naval forces.[44][18][45]

The Sentinelese scoured the abandoned shipwrecks to salvage iron for their weaponry.[8][43] M. A. Mohammad, a scrap dealer who won a government contract to dismantle the Primrose wreck (about 300 feet (91 m) from the shoreline) and assembled men for the purpose, recorded friendly exchange of fruits and small metal scraps with the Sentinelese, who often canoed to the workplace at low tide:[8][46]

After two days, in the early morning when it was low tide we saw three Sentinelese canoes with about a dozen men about fifty feet away from the deck of Primrose. We were skeptical and scared and had no other solution but to bring out our supply of bananas and show it to them to attract them and minimize any chance of hostility. They took the bananas and came up on board of Primrose and were frantically looking around for smaller pieces of metal scrap......They visited us regularly at least twice or thrice in a month while we worked at the site for about 18 months.....

Government of India

In 1956, the Government of India declared North Sentinel Island a tribal reserve and prohibited travel within 3 miles (4.8 km) of it.[17][47][48] Photography is prohibited.[49] A constant armed patrol prevents intrusions by outsiders.[50]

T. N. Pandit (1967–1991)

In 1967, a group of 20 people, comprising the governor, armed forces and naval personnel, were led by T. N. Pandit, an anthropologist working for the Anthropological Survey of India, to North Sentinel Island to explore it and befriend the Sentinelese.[51][48][18] This was the first visit to the island by a professional anthropologist.[4] Through binoculars, the group saw several clusters of Sentinelese along the coastline, who retreated into the forest as the team advanced. The team followed their footprints and after about a kilometer, found a group of 18 lean-to huts made from grass and leaves that showed signs of recent occupation as evidenced by the still-burning fires at the corners of the hut. The team also discovered raw honey, skeletal remains of pigs, wild fruits, an adze, a multi-pronged wooden spear, bows, arrows, cane baskets, fishing nets, bamboo pots and wooden buckets. Metal-working was evident. The team failed to establish any contact and withdrew after leaving gifts.[52]

The government was aware that leaving the Sentinelese (and the area) completely isolated and ceasing to claim any control would lead to rampant illegal exploitation of the natural resources by the numerous mercenary outlaws who took refuge in those regions, and probably contribute to the Sentinelese's extinction. Accordingly, in 1970, an official surveying party landed at an isolated spot on the island and erected a stone tablet, atop a disused native hearth, that declared the island part of India.[18]

During the 1970s and 1980s, Pandit undertook several visits to the island, sometimes as an "expert advisor" in tour parties including dignitaries who wished to encounter an aboriginal tribe.[18][8] Beginning in 1981, he regularly led official expeditions with the purpose of establishing friendly contact.[53] Many of these got a friendly reception, with hordes of gifts left for them,[4] but some ended in violent encounters, which were mostly suppressed.[8][54] Some of the expeditions (1987, 1992, et al.) were entirely documented on film.[4] Sometimes the Sentinelese waved and sometimes they turned their backs and assumed a "defecating" posture, which Pandit took as a sign of their not being welcome. On some occasions, they rushed out of the jungle to take the gifts but then attacked the party with arrows.[18] Other obscene gestures in response to contact parties, such as swaying of penises, have been noted.[55] On some of his visits, Pandit brought some Onge to the island to try to communicate with the Sentinelese, but the attempts were usually futile and Pandit reported one instance of angering the Sentinelese.[51][56]

National Geographic (1974)

In early 1974, a National Geographic film crew went to the island with a team of anthropologists (including Pandit), accompanied by armed police, to film a documentary, Man in Search of Man. They planned to spread the operation of gift-giving over the course of three days and attempt to establish friendly contact. When the motorboat broke through the barrier reefs, the locals emerged from the jungle and shot arrows at it. The crew landed at a safe point on the coast and left gifts in the sand, including a miniature plastic car, some coconuts, a live pig, a doll, and aluminum cookware.[54]

The Sentinelese followed up by launching another volley of arrows, one of which struck the documentary director in his thigh. The man who wounded the director withdrew to the shade of a tree and laughed proudly while others speared and buried the pig and the doll. They left afterward, taking the coconuts and cookware.[8][57] This expedition also led to the first photograph of the Sentinelese, published by Raghubir Singh in National Geographic magazine, where they were presented as people for whom "arrows speak louder than words".[56]

1991 expedition

In 1991, the first instances of peaceful contact were recorded in the course of two routine expeditions by an Indian anthropological team consisting of various representatives of diverse governmental departments and Madhumala Chattopadhyay.[58][18][59]

During a 4 January 1991 visit, the Sentinelese approached the party without weaponry for the first time. They collected coconuts that were offered but retreated to the shore as the team gestured for them to come closer. The team returned to the main ship, MV Tarmugli. It returned to the island in the afternoon to find at least two dozen Sentinelese on the shoreline, one of whom pointed a bow and arrow at the party. Once a woman pushed the arrow down, the man buried his weapons in the beach and the Sentinelese approached quite close to the dinghies for the first time. The Director of Tribal Welfare distributed five bags of coconuts hand-to-hand.[18]

Pandya comments:[60]

Those present in the defining moment of physical contact now wished to extract professional mileage from the fact of being actually 'touched' by the Sentinelese during the gift giving exercise. Every participating member of the contact party wanted to take the credit of being the first to 'touch the Sentinelese,' as if it were a great mystical moment of transubstantiation wherein the savage hostile reciprocated a gesture of civilized friendship. Who touched and who was touched during the contact event became an emotionally charged issue within various sectors of the administration where claims and counter-claims were sought to be established with earnestness and vigor...it is interesting to note the range of political and cultural significance invested in this specific event of contact.

Pandit and Madhumala took part in a second expedition on 24 February. The Sentinelese again appeared without weapons, jumped on the dinghies and took coconut sacks. They were also curious about a rifle hidden in the boat, which Chattopadhay believed they saw as a source of iron.[43][51]

In light of the friendly exchanges with the scrap dealers' team and Portman's observations in 1890, Pandya believes that the Sentinelese used to be visited by other tribes.[61]

Later contact

The series of contact expeditions continued until 1994, with some of them even attempting to plant coconut trees on the island.[62] The programs were then abandoned[8][18] for nearly nine years.[4] The Indian government maintained a policy of no deliberate contact, intervening only in cases of natural calamities that might pose an existential threat or to thwart poachers.[63]

A likely reason for the termination of these missions was that the Sentinelese did not let most of the post-Pandit contact teams get near them.[18] The teams usually waited until the armed Sentinelese retreated, then left gifts on the beach or set them adrift toward shore.[8] The government was also quite concerned about the possibility of harm to the Sentinelese by an influx of outsiders—a result of them projecting a relatively friendly image.[63] Photos of the 1991 expedition were removed from public display and use of them was restricted by the government.[63]

The next expedition occurred in April 2003, when a canoe built by the Onges was gifted to the visitors.[4] There were further expeditions (some aerial) in 2004 and 2005 to evaluate the effects of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which caused massive tectonic changes to the island: it was enlarged by a merger with nearby small islands, and the sea floor was raised by about 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in), exposing the surrounding coral reefs to air and destroying the shallow lagoons, which were the Sentinelese's fishing grounds.[64] The expeditions counted a total of 32 Sentinelese scattered over three places but did not find any bodies.[6] The Sentinelese responded to these aerial expeditions with hostile gestures, which led many to conclude that the community was mostly unaffected and had survived the calamity. Pandya argues that Sentinelese hostility is a sign of the physical as well as the cultural resilience of the community.[65]

The Sentinelese generally received the post-tsunami expeditions in a friendly manner. They approached the visiting parties, which carried no arms or shields as they had in earlier expeditions, unarmed.[4]

In 2014, an aerial expedition followed by a circumnavigation investigated the effects of a forest fire. Important data was gathered and the expedition recorded that the fire did not seem to have affected the populace. They exhibited a balance of ages and sexes, with a number of young children. Friendly hand gestures were noted but the visitors did not go very close to the island. The 2014 expedition also recorded that the Sentinelese had adapted to the changes to their fishing grounds, and were using their canoes to travel up to half a kilometre (a third of a mile) from the shore.

Deaths of two fishermen (2006)

On 27 January 2006, Indian fishermen Sunder Raj and Pandit Tiwari, who had been attempting to illegally harvest crabs off North Sentinel Island, drifted towards the island after their boat's makeshift anchor failed during the night. They did not respond to warning calls from passing fishermen, and their boat drifted into the shallows near the island,[66] where a group of Sentinelese warriors attacked the boat and killed the fishermen with axes.[67] According to one report, the bodies were later put on bamboo stakes facing out to sea like scarecrows.[68] Three days later, an Indian Coast Guard helicopter, dispatched for the purpose, found the buried bodies.[69][8][66] When the helicopter tried to retrieve them, it was attacked by Sentinelese armed with spears and arrows and the mission was soon abandoned.[70][71] There were contrasting views in the local community as to whether the Sentinelese ought to be prosecuted for the murder.[72]

Pandya hypothesizes that the aggressive response might have been caused by the sudden withdrawal of those gift-carrying expeditions, which was not influenced or informed by any acts of the Sentinelese.[63] He also notes that whilst the images of the hostile Sentinelese (captured by the helicopter sorties) were heavily propagated in the media, the images of them burying the dead were never released. This selective display led to an effective negation of the friendly images that were circulated in the aftermath of the 1991 contact (which have been already taken out of public display) and restored the 1975 National Geographic narrative.[72]

Death of a missionary (2018)

In November 2018, John Allen Chau, a 26-year-old American,[73] trained and sent by the US-based Christian missionary organization All Nations,[74] travelled to North Sentinel Island with the aim of contacting and living among the Sentinelese[74] in the hope of converting them to Christianity.[73][75][9][76] Chau did not seek the necessary permits required to visit the island[77][78] and traveled illegally to the island by bribing local fishermen.[79] He expressed a clear desire to convert the tribe and awareness of the risk of death he faced and of the illegality of his visits, writing, "Lord, is this island Satan's last stronghold where none have heard or even had the chance to hear your name?", "The eternal lives of this tribe is at hand", and "I think it's worthwhile to declare Jesus to these people. Please do not be angry at them or at God if I get killed...Don't retrieve my body."[80][81][82]

On 15 November, Chau attempted his first visit in a fishing boat, which took him about 500–700 metres (1,600–2,300 ft) from shore.[79] The fishermen warned Chau not to go farther, but he canoed toward shore with a waterproof Bible. As he approached, he attempted to communicate with the islanders[73] and to offer gifts, but he retreated after facing hostile responses.[83][82] On another visit, Chau recorded that the islanders reacted to him with a mixture of amusement, bewilderment and hostility. He attempted to sing worship songs to them, and spoke to them in Xhosa, after which they often fell silent. Other attempts to communicate ended with them bursting into laughter.[83] They apparently communicated with "lots of high pitched sounds" and gestures.[84] Eventually, according to Chau's last letter, when he tried to hand over fish and gifts, a boy shot a metal-headed arrow that pierced the Bible he was holding in front of his chest, after which he retreated again.[83]

On his final visit, on 17 November, Chau instructed the fishermen to leave without him.[76] The fishermen later saw the islanders dragging Chau's body, and the next day they saw his body on the shore.[79]

Police subsequently arrested seven fishermen for assisting Chau to get close to the restricted island.[82] His death was treated as a murder, but there was no suggestion that the Sentinelese would be charged[85] and the U.S. government confirmed that it did not ask the Indian government to press charges against the tribe.[86][87] Indian officials made several attempts to recover Chau's body but eventually abandoned those efforts. An anthropologist involved in the case told The Guardian that the risk of a dangerous clash between investigators and the islanders was too great to justify any further attempts.[88]

References

- Wire Staff (22 November 2018). "'Adventurist' American Killed by Protected Andaman Tribe on Island Off-Limits to Visitors". The wire. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Foster, Peter (8 February 2006). "Stone Age tribe kills fishermen who strayed on to island". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Dobson, Jim (21 November 2018). "A Human Zoo on the World's Most Dangerous Island? The Shocking Future of North Sentinel". Forbes. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "The Sentineles of Andaman & Nicobar Islands". The Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups in India : Privileges and Predicaments. Anthropological Survey of India. 2016. pp. 659–668. ISBN 9789350981061.

- "North Sentinel". The Bay of Bengal Pilot. Admiralty. London: United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. 1887. p. 257. OCLC 557988334.

- Pandya 2009, p. 362.

- Harrer, Heinrich (1977). Die letzten Fünfhundert: Expedition zu d. Zwergvölkern auf d. Andamanen [The last five hundred: Expedition to the dwarf peoples in the Andaman Islands] (in German). Berlin: Ullstein. ISBN 978-3-550-06574-3. OCLC 4133917. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Pandya, Vishvajit (2009). "Through Lens and Text: Constructions of a 'Stone Age' Tribe in the Andaman Islands". History Workshop Journal (67): 173–193. JSTOR 40646218.

- "American 'killed by arrow-wielding tribe'". BBC News. 21 November 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Bagla, Pallava; Stone, Richard (2006). "After the Tsunami: A Scientist's Dilemma". Science. 313 (5783): 32–35. doi:10.1126/science.313.5783.32. JSTOR 3846572. PMID 16825546.

- Enumeration of Primitive Tribes in A&N Islands: A Challenge (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2014.

The first batch could identify 31 Sentinelese. The second batch could count altogether 39 Sentinelese consisting of male and female adults, children and infants. During both the contacts the enumeration team tried to communicate with them through some Jarawa words and gestures, but, Sentinelese could not understand those verbal words.

- "Forest Statistics – Department of Environment & Forests, Andaman & Nicobar Islands" (PDF). 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- "Census of India 2011 Andaman & Nicobar Islands" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Government of India, Ministry of Tribal Affairs (24 February 2016). "Tribals in A & N Islands". Press Information Bureau. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Burman, B. K. Roy, ed. (1990). Cartography for Development of Outlying States and Islands of India: Short Papers Submitted at NATMO Seminar, Calcutta, December 3–6, 1990. National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organisation, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India. p. 203. OCLC 26542161.

- Weber, George. "The Tribes: Chapter 8". andaman.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Burton, Adrian (2012). "A world of their own". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 10 (7): 396. doi:10.1890/1540-9295-10.7.396. JSTOR 41811425.

- Goodhart, Adam (2000). "The Last Island of the Savages". The American Scholar. 69 (4): 13–44. JSTOR 41213066.

- Portman, Maurice Vidal (1899). "XVIII: The Jàrawas". A History of Our Relations with the Andamanese. II. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. p. 728. OCLC 861984. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Pandit 1990, p. 14.

- Pandya 2009, p. 361.

- Pandya 2009, p. 346.

- Shammas, John (22 April 2015). "Mysterious island is home to 60,000-year-old community who KILL outsiders". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "The Forbidden Island". Neatorama. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Zide, Norman; Pandya, Vishvajit (1989). "A Bibliographical Introduction to Andamanese Linguistics". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (4): 639–651. doi:10.2307/604090. JSTOR 604090.

- Moseley, Christopher (2007). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. p. 342. ISBN 9780700711970.

- "Chapter 8: The Tribes". web.archive.org. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Pandit 1990, p. 21-22.

- Dutta, Prabhash K. (21 November 2018). "Beyond killing of American national: Sovereign citizens of India". India Today. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "List of notified Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). Census India. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Gettleman, Jeffrey (21 November 2018). "American Is Killed by Bow and Arrow on Remote Indian Island". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Westmass, Reuben. "North Sentinel Island Is Home to the Last Uncontacted People on Earth". curiosity.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Sarkar, Jayanta (1997). "Befriending the Sentinelese of the Andamans: A Dilemma". In Pfeffer, Georg; Behera, Deepak Kumar (eds.). Development Issues, Transition and Change. Contemporary Society: Tribal Studies. 2. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-642-2. LCCN 97905535. OCLC 37770121. OL 324654M.

- McGirk, Tim (10 January 1993). "Islanders running out of isolation: Tim McGirk in the Andaman Islands reports on the fate of the Sentinelese". The Independent. London.

- Weber, George. "Chapter 8: The Tribes; Part 6. The Sentineli". The Andamanese. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- Pandya 2009, p. 41.

- Kavita, Arora (2018). Indigenous Forest Management in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Springer. pp. 17–100. ISBN 978-3-030-00032-5.

- Pfeffer, Georg; Behera, Deepak Kumar (1997). Contemporary Society: Developmental Issues, Transition, and Change. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170226420.

- "Sentinelese". survivalinternational.org. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Temple, R. C.; Bare, H. Bloomfield (1899). "Journal of the Society for Arts, Vol. 48, no. 2457". The Journal of the Society of Arts. 48 (2457): 105–136. JSTOR 41335348.

- Sarkar, S. S. (1962). "The Jarawa of the Andaman Islands". Anthropos. 57 (3/6): 670–677. JSTOR 40455833.

- Pandit 1990, p. 15.

- Tewari, Debayan (3 December 2018). "When the Sentinelese shun bows and arrows to welcome outsiders". The Economic Times. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- UPI Archives (25 August 1981). "Twenty-eight sailors shipwrecked for nearly two weeks off a..." UPI. UPI. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Mottram, Dennis (22 December 2010). "North Sentinel Island, Captain Robert Fore and previously unseen photographs of the 1981 Primrose rescue". eternalidol.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018.

- Pandya 2009, p. 342-43.

- Whiteside, Philip (21 November 2018). "US man killed by tribe after ignoring ban on visiting remote North Sentinel island". Sky News. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Sengar, Resham. "Know how 60,000-year-old human tribe of secluded North Sentinel Island behaves with outsiders". Times of India Travel. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Bhatnagar, Gaurav Vivek (23 November 2018). "Centre Ignored ST Panel Advice on Protecting Vulnerable Andaman Tribes". The Wire. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Pandya 2009, p. 334.

- Sharma, Shantanu Nandan (24 November 2018). "Surprised the Sentinelese killed someone: First anthropologist to enter North Sentinel island". The Economic Times. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Pandit 1990, p. 17-20.

- Pandit 1990, p. 13.

- Pandya 2009, p. 357.

- Pandya 2009, p. 358.

- Pandya 2009, p. 330.

- Pandit 1990, p. 24-25.

- Pandya, Vishvajit (16 April 2009). In the Forest. ISBN 9780761842729.

- Sengupta, Sudipto (30 November 2018). "Madhumala Chattopadhyay, the woman who made the Sentinelese put their arrows down". The Print. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Pandya 2009, p. 331.

- Pandya 2009, p. 343.

- Pandya 2009, p. 332.

- Pandya 2009, p. 333.

- Pandya 2009, p. 347.

- Pandya 2009, p. 336.

- Foster, Peter (8 February 2006). "Stone Age tribe kills fishermen who strayed on to island". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- McDougall, Dan (12 February 2006). "Survival comes first for Sentinel islanders – the world's last 'stone-age' tribe". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- All India – Agence France-Presse (25 November 2018). "Cops Retreat After Andaman Tribe Seen Armed With Bows And Arrows". ndtv.com. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Pandya 2009, p. 340.

- Som, Vishnu (23 November 2018). "Attacked By Andaman Tribe, Coast Guard Officer's Terrifying Account". NDTV. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Banerjie, Monideepa (25 November 2018). "Cops Studying Rituals of Tribe That Killed US Man To Recover His Body". NDTV. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Pandya 2009, p. 349-52.

- Slater, Joanna (21 November 2018). "'God, I don't want to die,' U.S. missionary wrote before he was killed by remote tribe on Indian island". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- News Corp (26 November 2018). "Police face-off with Sentinelese tribe as they struggle to recover slain missionary's body". News.com.au. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Roy, Sanjib Kumar (21 November 2018). "American killed on remote Indian island off-limits to visitors". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Reuters. "US man killed by remote tribe was trying to spread Christianity". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Chatterjee, Tanmay; Lama, Prawesh (23 November 2018). "American national John Allen Chau violated every rule in the book to meet the Sentinelese". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018.

- Bhardwaj, Deeksha (28 November 2018). "John Allen Chau 'lost his mind', was aware of dangers of North Sentinel Island, say friends". ThePrint. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018.

- Banerjie, Monideepa (22 November 2018). "American Paid Fishermen Rs. 25,000 For Fatal Trip To Andamans". NDTV. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Slater, Joanna (23 November 2018). ""Satan's Last Stronghold...?" US Man Wrote Before Death on Andaman Island". NDTV. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Chavez, Nicole (25 November 2018). "Indian authorities struggle to retrieve US missionary feared killed on remote island". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Firstpost Staff. "US tourist killed by tribe in Andaman and Nicobar's North Sentinel Island, seven arrested in connection with murder". www.firstpost.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Jeffrey Gettleman; Hari Kumar; Kai Schultz (23 November 2018). "A Man's Last Letter Before Being Killed on a Forbidden Island". New York Times.

- Slater, Joanna; Gowen, Annie (23 November 2018). "Fear and faith: Inside the last days of an American missionary died on tribe's remote Indian Ocean island". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- BBC News (25 November 2018). "Indian authorities struggle to retrieve US missionary feared killed on remote island". BBC. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Indo Asian News Service (8 February 2019). "US not seeking action against Sentinelese tribe for killing missionary". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019.

- "International Religious Freedom". United States Department of State. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Michael Safi; Denis Giles (28 November 2018). "India has no plans to recover body of US missionary killed by tribe". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Pandit, T. N. (1990). The Sentinelese. Kolkata: Seagull Books. ISBN 978-81-7046-081-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pandya, Vishvajit (2009). In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858-2006). Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761842729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weber, George (2005). "The Andamanese". The Lonely Islands. The Andaman Association. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013.

External links

- Video "SENTINELESE : World's Most Isolated Tribe", includes clips of friendly contact by the Anthropological Survey of India as well as another clip of National Geographic crew's attempt at contact being rebuffed by the Sentinelese

- "Leave the Sentinelese alone, an interview with the T N Pandit of Anthropological Survey of India

- Madhumala Chattopadhyay: An Anthropologist's Moment of Truth, discusses first friendly contact with Sentinelese

- Administration in India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands has finally decided upon a policy of minimal interference

- "The most isolated tribe in the world?". Uncontacted tribes. Survival International.

- McDougall, Dan (11 February 2006). "Survival comes first for the last Stone Age tribe world". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2015.