Rajaraja I

Rajaraja I, born Arulmoli Varman[5][6][7], often described as Rajaraja the Great, was a Chola emperor (reigned c. 985–1014) chiefly remembered for reinstating the Chola power and ensuring its supremacy in south India and Indian Ocean.

| Rajaraja I | |

|---|---|

| Rājakesarī[3][4] Mummudi Cholan[5] | |

Modern statue of Rajaraja Cholan in Thanjavur | |

| Reign | c. 985 – c. 1014 |

| Predecessor | Uttama Chola aka Madurantaka |

| Successor | Rajendra Chola I |

| Born | Arulmoḷi Varman c. 947 |

| Died | 1014 (aged 66–67) |

| Issue |

|

| Dynasty | Chola Dynasty |

| Father | Sundara Chola |

| Mother | Vanavanmahadevi |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| List of Chola kings and emperors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Cholas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interregnum (c. 200 – c. 848) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medieval Cholas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Later Cholas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chola society | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

His extensive empire included the Pandya country (southern Tamil Nadu), the Chera country (Malabar Coast and western Tamil Nadu) and northern Sri Lanka. He also acquired the Lakshadweep and Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean. Campaigns against the Western Gangas (southern Karnataka) and Chalukyas extended the Chola influence as far as the Tungabhadra River. On the eastern coast he battled with the Chalukyas for the possession of Vengi (the Godavari districts).[8][9][10][11]

Rajaraja, an able administrator, also built the great Brihadisvara Temple at the Chola capital Thanjavur.[12] The temple is regarded as the foremost of all temples in the medieval south Indian architectural style. During his reign, the texts of the Tamil poets Appar, Sambandar and Sundarar were collected and edited into one compilation called Thirumurai.[9][13] He initiated a massive project of land survey and assessment in 1000 CE which led to the reorganisation of the country into individual units known as valanadus.[14][15] Rajaraja died in 1014 CE and was succeeded by his son Rajendra Chola I.

Early life

According to the Thiruvalangadu copper-plate inscription, Rajaraja's original name was Arulmoḷi (also transliterated as Arulmozhi) Varman, literally "blessed tongued".[5][16] He was born around 947 CE in the Aipassi month, on the day of Sadhayam star.[17] He was a son of the Chola king Parantaka II (alias Sundara) and queen Vanavan Mahadevi.[18] He had an elder brother - Aditya II,[6] and an elder sister - Kundavai.[19]

Rajaraja's ascension ended a period of rival claims to the throne, following the death of his grandfather Parantaka I. After Parantaka I, his son Gandaraditya ascended the throne. When Gandaraditya died, his son Uttama was a minor, so the throne passed on to Parantaka I's younger son Arinjaya. Arinjaya died soon, and was succeeded by his son Parantaka II. It was decided that the throne would pass on to Uttama after Parantaka II: this decision was most probably that of Parantaka II, although the Thiruvalangadu inscription of Rajaraja's son Rajendra I claims that it was made by Rajaraja.[6]

Rajaraja's elder brother died before him, and after the death of Uttama, Rajaraja ascended the throne in June–July 985.[6] Known as Arumoḷi Varman until this point, he adopted the name Rajaraja, which literally means "King among Kings".[20] He also called himself Shivapada Shekhara (IAST: Śivapada Śekhara), literally, "the one who places his crown at the feet of Shiva".[21]

Military conquests

Rajaraja inherited a kingdom whose boundaries were limited to the traditional Chola territory centred around Thanjavur-Tiruchirappalli region.[5] At the time of his ascension, the Chola kingdom was relatively small, and was still recovering from the Rashtrakuta invasions in the preceding years. Rajaraja turned it into an efficiently-administered empire which possessed a powerful army and a strong navy. During his reign, the northern kingdom of Vengi became a Chola protectorate, and the Chola influence on the eastern coast extended as far as Kalinga in the north.[6]

A number of regiments are mentioned in the Thanjavur inscriptions.[22][23] These regiments were divided into elephant troops, cavalry and infantry and each of these regiments had its own autonomy and was free to endow benefactions or build temples.[22]

Initial campaigns against neighbours

It is known that Rajaraja celebrated a major victory at Kandalur Salai (south Kerala) in c. 988 CE. This battle is remembered with the famous phrase "Kandalur Salai Kalamarutta". The engagement seemed to be an effort of the Chola navy or a combined effort of the navy and the army.[24] The salai originally belonged to the Ay chief, a vassal of the Pandya king at Madurai, in the mid-860s. Involvement of either Chera or Pandya warriors in this battle remain uncertain.[24] The conquest of Vizhinjam by the general of Rajaraja (mentioned in the Thiruvalangadu Plates) is sometimes equated with this battle.[11] Rajaraja's inscriptions start to appear in Kanyakumari district in the 990s and in Trivandrum district in early 1000s.[11]

According to Thiruvalangadu Plates, just after killing the "Andhra Bhima", Rajaraja conquered "the Parasurama kingdom" (c. 1002-03 CE), probably identical with Kerala.[24] The multiple references to the conquest of "Kudamalainadu" or "Malainadu" may also be a reference to the conquest of Kerala (see below, Kudamalainadu is generally identified with Coorg).[11] Tiruppalanam and Tiruvenkatu (999 and 1000 CE) inscriptions mention the gift of an idol by king from the booty obtained in Malainadu and the treasures taken from the Chera king.[11]

The Senur inscription (1005 CE) of Rajaraja states that he destroyed the Pandya capital Madurai; conquered the "haughty kings" of Kollam (Venatu), Kolla-desham (Musika), and Kodungallur (Chera); and that the "kings of the sea" waited on him.[24] The 1014 CE Thanjavur inscriptions credit him with victories over the Chera and the Pandya in "Malainadu".[25] Some of these victories in Malainadu were perhaps won by prince Rajendra Chola for his father.[11]

After defeating the Pandyas, Rajaraja adopted the title Pandya Kulashani ("Thunderbolt to the Race of the Pandyas"), and the Pandya country came to be known as "Rajaraja Mandalam" or "Rajaraja Pandinadu".[25] While describing the Rajaraja's campaign in trisanku kastha (the south), the Thiruvalangadu Grant of Rajendra I states that he seized certain Amarabhujanga.[26] Identification of this prince (Pandya prince?, a general of the Pandya king?[26], Kongu Chera prince[11]?) remains unresolved.[11] Kongu Desa Rajakkal, a chronicle of the Kongu Nadu region, suggests that this general later shifted his allegiance to Rajaraja, and performed the Chola king's kanakabhisheka ceremony.[26]

After consolidating his rule in the south, Rajaraja assumed the title Mummudi Chola ("the Chola who Wears Three Crowns"), a reference to his control over the three Tamil kingdoms of the Cholas, the Pandyas, and the Cheras.[5]

Conquest of Sri Lanka

In 993, Rajaraja invaded Sri Lanka, which is called Ila-mandalam in the Chola records.[27] This invasion most probably happened during the reign of Mahinda V of Anuradhapura, who according to the Chulavamsa chronicle, had fled to Rohana (Ruhuna) in south-eastern Sri Lanka because of a military uprising.[28] The Chola army sacked Anuradhapura, and captured the northern half of Sri Lanka. The Cholas established a provincial capital at the military outpost of Polonnaruwa, naming it Jananatha Mangalam after a title of Rajaraja.[28] The Chola official Tali Kumaran erected a Shiva temple called Rajarajeshvara ("Lord of Rajaraja") in the town of Mahatittha (modern Mantota), which was renamed Rajaraja-pura.[28]

Comparing Rajaraja's campaign to the invasion of Lanka by the legendary hero Rama, the Thiruvalangadu inscription states:[5]

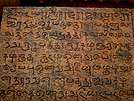

Thiruvalangadu copper plates[5]

In 1017, Rajaraja's son Rajendra I completed the Chola conquest of Sri Lanka.[29] The Cholas controlled Sri Lanka until 1070, when Vijayabahu I defeated and expelled them.[30]

Chalukyan conflict

In 998 CE, Rajaraja captured the regions of Gangapadi, Nolambapadi and Tadigaipadi (present day Karnataka).[31] Raja Chola extinguished the Nolambas, who were the feudatories of Ganga while conquering and annexing Nolambapadi.[32] The conquered provinces were originally feudatories of the Rashtrakutas.[33][34] In 973 CE, the Rashtrakutas were defeated by the Western Chalukyas leading to direct conflict with Cholas.[35] An inscription of Irivabedanga Satyashraya from Dharwar describes him as a vassal of the Western Chalukyas and acknowledges the Chola onslaught.[36] In the same inscription, he accuses Rajendra of having arrived with a force of 955,000 and of having gone on rampage in Donuwara thereby blurring the moralities of war as laid out in the Dharmasastras.[37] Historians like James Heitzman and Wolfgang Schenkluhn conclude that this confrontation displayed the degree of animosity on a personal level between the rulers of the Chola and the Chalukya kingdoms drawing a parallel between the enmity between the Chalukyas of Badami and the Pallavas of Kanchi.[38][39]

By 1004 AD, the Gangavadi province was conquered by Rajaraja.[40] The Changalvas who ruled over the western part of the Gangavadi province and the Kongalvas who ruled over Kodagu were turned into vassals.[41] The Chola general Panchavan Maraya who defeated the Changalvas in the battle of Ponnasoge and distinguished himself in this affair was rewarded with Arkalgud Yelusuvira-7000 territory and the title Kshatriyasikhamani.[42] The Kongalvas, for the heroism of Manya, were rewarded with the estate of Malambi (Coorg) and the title Kshatriyasikhamani.[41] There were encounters between the Cholas and the Hoysalas, who were vassals of the Western Chalukyas. An inscription from the Gopalakrishna temple at Narasipur dated to 1006 records that Rajaraja's general Aprameya killed minister Naganna and other generals of the Hoysalas.[43] A similar inscription in Channapatna also describes Rajaraja defeating the Hoysalas.[44] Vengi kingdom was ruled by Jata Choda Bhima of the Eastern Chalukyas dynasty.[35] Jata Choda Bhima was defeated by Rajaraja and Saktivarman was placed on the throne of Vengi as a viceroy of the Chola Dynasty.[35][45] After the withdrawal of the Chola army, Bhima captured Kanchi in 1001 CE. Rajaraja expelled and killed the Andhra king called Bhima before re-establishing Saktivarman I on the throne of Vengi again.[46] Rajaraja gave his daughter Kundavai in marriage to his next viceroy of Vengi Vimaladitya which brought about the union of the Chola Dynasty and the Eastern Chalukya Kingdom and which also ensured that the descendants of Rajaraja would rule the Eastern Chalukya kingdom in the future.[45]

Kalinga conquest

The invasion of the kingdom of Kalinga occurred after the conquest of Vengi.[47]

Conquest of Kudamalainadu/Malainadu

There are multiple references to the conquest of "Kudamalainadu" or "Malainadu" and the capture of the fort of "Udagai" by king Rajaraja (from c. 1000 onwards).[11][48] The word Kudagumalai-nadu is substituted in place of Kudamalainadu in some of the inscriptions found in Karnataka and this region has been generally identified with Coorg (Kudagu).[11][49]

It is said that the king conquered Malainadu for the sake of messengers in one day after crossing 18 mountain passes (Vikrama Chola Ula).[11] Kulottunga Chola Ula makes reference to Rajaraja cutting off 18 heads and setting fire to Udagai.[24] Kalingathupparani mentions the institution of Chadaya Nalvizha in Udiyar Mandalam, the capture of Udagai, and the plunder of several elephants from there.[11] Tiruppalanam inscription (999 CE) mentions the gift of an idol by king from the booty obtained in Malainadu.[11][50][51][52]

Naval expedition

One of the last conquests of Rajaraja was the naval conquest of the islands of Maldives ("the Ancient Islands of the Sea Numbering 1200").[53][11] The naval campaign was a demonstration of the Chola naval power in the Indian Ocean.[11]

The Cholas controlled the area around of Bay of Bengal with Nagapattinam as the main port. The Chola Navy also had played a major role in the invasion of Sri Lanka.[54] The success of Rajaraja allowed his son Rajendra Chola to lead the Chola invasion of Srivijaya, carrying out naval raids in South-East Asia and briefly occupying Kadaram.[8][55]

Personal life

Rajaraja indulged in a lot of queens some of whom were Dantisakti Vitanki aka Lokamadevi, Vanavan Madevi aka Thiripuvāna Mādēviyār, Panchavan Madeviyar, Chola Mahadevi, Trailokya Mahadevi, Lata Mahadevi, Prithvi Mahadevi, Meenavan Mahadevi, Viranarayani and Villavan Mahadevi.[56][57][58][59] He had at least three daughters. He had a son Rajendra with Thiripuvāna Mādēviyār.[60][61][62] He had his first daughter Kundavai with Ulaga Madeviyar. Kundavai married Chalukya prince Vimaladithan. He had two other daughters named Mathevadigal and Ģangamādevi or Arumozhi Chandramalli.[59] Rajaraja died in 1014 CE in the Tamil month of Maka and was succeeded by Rajendra Chola I.[63]

Administration

Before the reign of Rajaraja I, parts of the Chola territory were ruled by hereditary lords and princes who were in a loose alliance with the Chola rulers.[67] Rajaraja initiated a project of land survey and assessment in 1000 CE which led to the reorganization of the empire into units known as valanadus.[14][15] From the reign of Rajaraja I until the reign of Vikrama Chola in 1133 CE, the hereditary lords and local princes were either replaced or turned into dependent officials.[67] This led to the king exercising a closer control over the different parts of the empire.[67] Rajaraja strengthened the local self-government and installed a system of audit and control by which the village assemblies and other public bodies were held to account while retaining their autonomy.[68][69][70] To promote trade, he sent the first Chola mission to China.[71]

His elder sister Kundavai assisted him in administration and management of temples.[72]

Officials

Rajendra Chola I was made a co-regent during the last years of Rajaraja's rule. He was the supreme commander of the northern and north-western dominions. During the reign of Raja Chola, there was an expansion of the administrative structure leading to the increase in the number of offices and officials in the Chola records than during earlier periods.[14] Villavan Muvendavelan, one of the top officials of Rajaraja figures in many of his inscriptions.[73] The other names of officials found in the inscriptions are the Bana prince Narasimhavarman, a general Senapathi Krishnan Raman, the Samanta chief Vallavaraiyan Vandiyadevan, the revenue official Irayiravan Pallavarayan and Kuruvan Ulagalandan, who organised the country-wide land surveys.[74]

Religious policy

Rajaraja was a follower of Shaivism but he was tolerant towards other faiths and had several temples for Vishnu constructed and encouraged the construction of the Buddhist Chudamani Vihara at the request of the Srivijaya king Sri Maravijayatungavarman. Rajaraja dedicated the proceeds of the revenue from the village of Anaimangalam towards the upkeep of this Vihara.[75]

Society

The Hindu caste system was prevalent and each caste lived in its own neighborhood called cheri, for example Kammanacheri (artisans), Paraicheri, Teendacheri (untouchables), etc. The Thanjavur inscriptions mention a number of villages where Paraicheri and Teendacheri were located. In all these instances, it is found that these colonies, i.e., the Paraicheris and Teendacheris were exempted from paying tax (land).[76] In another epigraph, since Paraicheri is mentioned separately and in addition to Teendacheri, it is believed that the untouchables were different from the Paraiyas.[77] The Paraiyar settlements were near agricultural lands and irrigation channels. In Chola epigraphs, the Paraiyars are called ulaparaiyars, that is Paraiyars who were engaged in cultivation. An inscription of Rajaraja mentions that ulaparaiyars occupied kilacheri and melaparaicheri in Venkondi village.[78] According to M. Arokiaswami, the Kammalar (Vishwakarma) were given a more privileged status during the reign of Rajaraja as they played an active role in the construction of temples.[79]

Arts and architecture

Rajaraja embarked on a mission to recover the hymns after hearing short excerpts of Thevaram in his court.[80] He sought the help of Nambi Andar Nambi.[81] It is believed that by divine intervention Nambi found the presence of scripts, in the form of cadijam leaves half eaten by white ants in a chamber inside the second precinct in Thillai Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram.[82][81] The brahmanas (Dikshitars) in the temple opposed the mission, but Rajaraja intervened by consecrating the images of the saint-poets through the streets of Chidambaram.[82][83] Rajaraja thus became to be known as Tirumurai Kanda Cholan meaning one who saved the Tirumurai. Thus far Shiva temples only had images of god forms, but after the advent of Rajaraja, the images of the Nayanar saints were also placed inside the temple.[83] Nambi arranged the hymns of three saint poets Sambandar, Appar and Sundarar as the first seven books, Manickavasagar's Tirukovayar and Tiruvacakam as the 8th book, the 28 hymns of nine other saints as the 9th book, the Tirumandiram of Tirumular as the 10th book, 40 hymns by 12 other poets as the 10th book, Tirutotanar Tiruvanthathi - the sacred anthathi of the labours of the 63 nayanar saints and added his own hymns as the 11th book.[84] The first seven books were later called as Tevaram, and the whole Saiva canon, to which was added, as the 12th book, Sekkizhar's Periya Puranam (1135) is wholly known as Tirumurai, the holy book. Thus Saiva literature which covers about 600 years of religious, philosophical and literary development.[84]

Brihadisvara Temple

In 1010 CE, Rajaraja built the Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur dedicated to Lord Shiva. The temple and the capital acted as a center of both religious and economic activity.[85] It is also known as Periya Kovil, RajaRajeswara Temple and Rajarajeswaram.[86][87] It is one of the largest temples in India and is an example of Dravidian architecture during the Chola period.[88] The temple turned 1000 years old in 2010.[89] The temple is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the "Great Living Chola Temples", with the other two being the Gangaikonda Cholapuram and Airavatesvara temple.[90]

The vimanam (temple tower) is 216 ft (66 m) high and is the tallest in the world. The Kumbam (the apex or the bulbous structure on the top) of the temple is carved out of a single rock and weighs around 80 tons.[91] There is a big statue of Nandi (sacred bull), carved out of a single rock measuring about 16 feet long and 13 feet high at the entrance. The entire temple structure is made out of granite, the nearest sources of which are about 60 km to the west of temple. The temple is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Tamil Nadu.[92]

Coins

Before the reign of Rajaraja the Chola coins had on the obverse the tiger emblem and the fish and bow emblems of the Pandya and Chera Dynasties and on the reverse the name of the King. But during the reign of Rajaraja appeared a new type of coins. The new coins had on the obverse the figure of the standing king and on the reverse the seated goddess.[93] The coins spread over a great part of South India and were also copied by the kings of Sri Lanka.[94]

Inscriptions

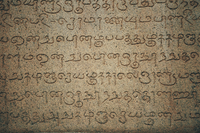

Due to Rajaraja's desire to record his military achievements, he recorded the important events of his life in stones. An inscription in Tamil from Mulbagal in Karnataka shows his accomplishments as early as the 19th year. An excerpt from such a Meikeerthi, an inscription recording great accomplishments, follows:[95]

Hail! Prosperity! In the 21st year of (the reign of) the illustrious Ko-Raja-Rajakesarivarman, alias the illustrious Rajaraja-deva, who, -while both the goddess of fortune and the great goddess of the earth, who had become his exclusive property, gave him pleasure,-was pleased to destroy the ships at Kandalur and conquered by his army, which was victorious in great battles, Vengai-nadu, Ganga-padi, Nulamba-padi, Tadigai-padi, Kudamalai-nadu, Kollam, Kalingam and Ira-mandalam, which is famed in the eight directions; who,-while his beauty was increasing, and while he was resplendent (to such an extent) that he was always worthy to be worshipped,-deprived the Seriyas of their splendour,-and (in words) in the twenty-first year of Soran Arumori, who possesses the river Ponni, whose waters are full of waves..[96][97]

Rajaraja recorded all the grants made to the Thanjavur temple and his achievements. He also preserved the records of his predecessors. An inscription of his reign found at Tirumalavadi records an order of the king to the effect that the central shrine of the Vaidyanatha temple at the place should be rebuilt and that, before pulling down the walls, the inscriptions engraved on them should be copied in a book. The records were subsequently re-engraved on the walls from the book after the rebuilding was finished.[98]

Another inscription from Gramardhanathesvara temple in South Arcot district dated in the seventh year of the king refers to the fifteenth year of his predecessor that is Uttama Choladeva described therein as the son of Sembiyan-Madeviyar.[99]

In popular culture

- Rajaraja Cholan, a 1973 Tamil film starring Sivaji Ganesan[100]

- Ponniyin Selvan by Kalki revolves around the life of Rajaraja, the mysteries surrounding the assassination of Aditya Karikalan and the subsequent accession of Uttama to the Chola throne[101]

- Nandipurathu Nayagi by Vembu Vikiraman revolves around the ascension of Uttama Chola to the throne and Rajaraja's naval expedition

- Rajaraja Cholan by Kathal Ramanathan

- Kandalur Vasantha Kumaran Kathai by Sujatha which deal with the situations leading Rajaraja to invade Kandalur

- Rajakesari and Cherar Kottai by Gokul Seshadri deal with the Kandalur invasion and its after-effects

- Bharat Ek Khoj, a 1988 historical drama in its episodes 22 and 23 portrays Raj Raja Chola.[102]

- Kaviri Mainthan, a 2007 novel by Anusha Venkatesh

See also

- List of Tamil monarchs

References

- Charles Hubert Biddulph (1964). Coins of the Cholas. Numismatic Society of India. p. 34.

- John Man (1999). Atlas of the year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 104.

- Charles Hubert Biddulph (1964). Coins of the Cholas. Numismatic Society of India. p. 34.

- John Man (1999). Atlas of the year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 104.

- Vidya Dehejia 1990, p. 51.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, p. 1.

- A. K. Seshadri 1998, p. 31.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- A Journey through India's Past by Chandra Mauli Mani p.51

- Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture by John Bowman p.264

- M. G. S. Narayanan 2013, p. 115-117.

- The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger p.347

- Indian Thought: A Critical Survey by K. Damodaran p.246

- A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century by Upinder Singh p.590

- Administrative System in India: Vedic Age to 1947 by U. B. Singh p.76

- A. K. Seshadri 1988, p. 31.

- Tamil Civilization: Quarterly Research Journal of the Tamil University. 3. Tamil University. 1985. pp. 40–41.

- Vidya Dehejia 2009, p. 42.

- A. K. Seshadri 1998, p. 32.

- Vidya Dehejia 1990, p. 49.

- R. S. Sharma 2003, p. 270.

- Seshachandrika: a compendium of Dr. M. Seshadri's works p.265

- Literary Genetics with Comparative Perspectives by Katir Makātēvan̲ p.25

- M. G. S. Narayanan 2013, p. 115-118.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, p. 238.

- V. Ramamurthy 1986, pp. 288-289.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, p. 2.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, p. 3.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, pp. 10-11.

- K. A. N. Sastri 1992, p. 36.

- Tamilian Antiquary (1907 - 1914) - 12 Vols. by Pandit. D. Savariroyan p.30

- Seminar on Social and Cultural History of Dharmapuri district p.46

- Mohan Lal Nigam (1975). Sculptural Heritage of Andhradesa. Sculptural Heritage of Andhradesa. p. 17.

- M. S. Krishna Murthy (1980). The Noḷambas: a political and cultural study, c750 to 1050 A.D. University of Mysore. p. 98.

- Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.398

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume 16, page 74

- Studying early India: archaeology, texts and historical issues, page 198

- The world in the year 1000, page 311

- History of India: a new approach by Kittu Reddy p.146

- Malini Adiga. The Making of Southern Karnataka: Society, Polity and Culture in the Early Medieval Period. Orient BlackSwan, 2006. p. 239.

- Baij Nath Puri. History of Indian Administration: Medieval period. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1975. p. 51.

- Ali, B. Sheik. History of the Western Gangas, Volume 1. Prasārānga, University of Mysore, 1976. p. 160.

- Epigraphia Indica, Volume 30, page 248

- Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Volume 21, page 200

- Gazetteer of the Nellore District: Brought Upto 1938 by Government Of Madras Staff, Government of Madras p.38

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The age of imperial Kanauj. Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. p. 154.

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904). The Early History of India. The Clarendon press. pp. 336–358.

- Chandra Mauli Mani. A Journey through India's Past (Great Hindu Kings after Harshavardhana). Northern Book Centre, 2009 - India - 132 pages. p. 51.

- Archaeological Survey of India, India. Dept. of Archaeology, India. Archaeological Survey. Epigraphia Indica, Volume 22. Manager of Publications, 1935. p. 225.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Archæological Survey of India, India. Department of Archaeology. South Indian Inscriptions: Tamil inscriptions of Rajaraja, Rajendra-Chola, and others in the Rajarajesvara Temple at Tanjavur. Superintendent, Government Press, 1983. p. 3.

- Gandhi Jee Roy. Diplomacy in ancient India. Janaki Prakashan, 1981 - History - 234 pages. p. 129.

- Gayatri Chakraborty. Espionage in Ancient India: From the Earliest Time to 12th Century A.D. Minerva Associates, 1990 - Political Science - 153 pages. p. 120.

- John Keay 2000, p. 215:"Rajaraja is supposed to have conquered twelve thousand old islands... a phrase meant to indicate the Maldives"

- Milo Kearney 2003, p. 70.

- Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia by Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja p.230

- S. R. Balasubrahmanyam. Middle Chola Temples: Rajaraja I to Kulottunga I (A.D. 985-1070). Oriental Press, 1977. p. 6.

- Documentation on Women, Children, and Human Rights. Sandarbhini, Library and Documentation Centre. 1994.

- Studies in Indian place names. Place Names Society of India. 1954. p. 58.

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy. Archaeological Survey of India. 1995. p. 7.

- P. V. Jagadisa Ayyar (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. p. 264.

- Early Chola art, page 183

- A Topographical List of Inscriptions in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala States: Thanjavur District, page 180

- Rāja Rāja, the great. Ananthacharya Indological Research Institute. 1987. p. 28.

- Edith Tömöry (1982). A History of Fine Arts in India and the West. Orient Longman. p. 246.

- Rakesh Kumar (2007). Encyclopaedia of Indian paintings. Anmol Publications. p. 4.

- V V Subba Reddy (2009). Temples of South India. Gyan Publishing House. p. 124.

- Precolonial India in Practice : Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra by Austin Cynthia Talbot Assistant Professor of History and Asian Studies University of Texas p.172

- Life/Death Rhythms of Ancient Empires - Climatic Cycles Influence Rule of Dynasties by Will Slatyer p.236

- The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.68

- Geeta Vasudevan 2003, pp. 62-63.

- Tamil Nadu, a real history by K. Rajayyan p.112

- Ancient system of oriental medicine, page 96

- South Indian inscriptions, India. Archaeological Survey, India. Dept. of Archaeology p.477

- South India heritage: an introduction by Prema Kasturi, Chithra Madhavan p.96

- Tamilian Antiquary (1907 - 1914) - 12 Vols. by Pandit. D. Savariroyan p.33

- Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi. Studies in Ancient Tamil Law and Society, Issue 47 of T.N.S.D.A. publication, Tamil Nadu (India). Dept. of Archaeology. Institute of Epigraphy, State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamilnadu, 1978. p. 100.

- Krishnaswamy Ranaganathan Hanumanthan. Untouchability: A Historical Study Upto 1500 A.D. : with Special Reference to Tamil Nadu. Koodal Publishers, 1979. p. 162.

- "Epigraphical Society of India". Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India, Volume 25. The Society, 1999. p. 95.

- Jawaharlal Nehru University. Centre for Historical Studies. Studies in History, Volume 11. Sage, 1995. p. 13.

- S. V. S. (1985). Raja Raja Chola, the high point of history. Authors Guild of India Madras Chapter. p. 54.

- John E. Cort 1998, p. 178.

- Norman Cutler 1987, p. 50.

- Geeta Vasudevan 2003, pp. 109-110.

- Kamil Zvelebil 1974, p. 191.

- Geeta Vasudevan 2003, p. 46.

- "Tamil Nadu – Thanjavur Periya Kovil – 1000 Years, Six Earthquakes, Still Standing Strong". Tamilnadu.com. 27 January 2014.

- South Indian Inscriptions – Vol II, Part I & II

- John Keay 2000, p. xix.

- "Endowments to the Temple". Archaeological Survey of India.

- "Tanjavur Periya Kovil Tamil Nadu". Tamilnadu.com. 5 December 2012.

- "About Chola temples". The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 185.

- Antiquities of India: An Account of the History and Culture of Ancient Hindustan by Lionel D. Barnett p.216

- Coins of India by C. J. Brown p.63

- "Rajaraja inscriptions". varalaaru.com.

- B. Lewis Rice 1905, p. 107.

- Archaeological Survey of India, India. Department of Archaeology,Volumes 9-10; Volume 49 of New imperial series,Volume 1 of South Indian Inscriptions. South Indian Inscriptions: Tamil and Sanskrit. Archaeological Survey of India, India. Department of Archaeology. Manager of Publications, 1890. pp. 94–95.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Eugen Hultzsch 1890, p. 8.

- S. R. Balasubrahmanyam, B. Natarajan, Balasubrahmanyan Ramachandran. Later Chola Temples: Kulottunga I to Rajendra III (A.D. 1070-1280), Parts 1070-1280. Mudgala Trust, 1979. p. 149.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Cine Quiz". The Hindu. 26 September 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Mani is likely to drop Ponniyin Selvan". Times of India. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- "What makes Shyam special". The Hindu. 17 January 2003. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

Bibliography

- A. K. Seshadri (1998). Sri Brihadisvara: The Great Temple of Thānjavūr. Nile.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- B. Lewis Rice (1905). Epigraphia Carnatica. 10, Part I. Mysore Archaeological Survey.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eugen Hultzsch (1890). South Indian inscriptions (1983 reprint). Archaeological Survey of India.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geeta Vasudevan (2003). Royal Temple of Rajaraja: An Instrument of Imperial Chola Power. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 0-00-638784-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- John E. Cort (1998). Open boundaries: Jain communities and culture in Indian history. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791437865.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- John Keay (2000). India, a History. London: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-00-638784-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- K. A. N. Sastri (1984) [1935]. The Cholas. Madras: University of Madras.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- K. A. N. Sastri (1992). "The Cōḷas". In R. S. Sharma; K. M. Shrimali (eds.). A Comprehensive history of India: A.D. 985-1206. People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- K. A. N. Sastri (2000) [1955]. A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195606868.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kamil Zvelebil (1974). A History of Indian literature. 10 (Tamil Literature). Otto Harrasowitz. ISBN 3-447-01582-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milo Kearney (2003). The Indian Ocean in World History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31277-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- M. G. S. Narayanan (2013). Perumāḷs of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy. CosmoBooks. ISBN 978-81-88765-07-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norman Cutler (1987). Songs of experience: the poetics of Tamil devotion. USA: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data. ISBN 0-253-35334-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- R. Rajalakshmi (1983). Tamil Polity, c. A.D. 600-c. A.D. 1300. Ennes.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- R. S. Sharma (2003). Early Medieval Indian Society. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-2523-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- T. S. Subramanian (27 November 2009). "Unearthed stone ends debate". The Hindu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- V. Ramamurthy (1986). N. Mahalingam (ed.). History of Kongu. ISIAC.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vidya Dehejia (2009). The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art. Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-231-51266-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vidya Dehejia (1990). Art of the Imperial Cholas. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51524-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Preceded by Uttama Chola |

Rajaraja I 985–1014 |

Succeeded by Rajendra Chola I |