Qutb Minar

The Qutb Minar, also spelled as Qutub Minar, is a minaret and "victory tower" that forms part of the Qutb complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Mehrauli area of Delhi, India.[2][3] Qutb Minar was 73-metres (239.5 feet) tall before the final, fifth section was added after 1369.[4] The tower tapers, and has a 14.3 metres (47 feet) base diameter, reducing to 2.7 metres (9 feet) at the top of the peak.[5] It contains a spiral staircase of 379 steps.[6][1]

| Qutb Minar | |

|---|---|

Minar in Delhi, India | |

| Coordinates | |

| Height | 72.5 metres (238 ft) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | 4 |

| Designated | 1993 (17th session) |

| Reference no. | 233 |

| Country | |

| Continent | Asia |

| Construction | Started by Qutb-ud-din Aibak / completed by his son-in-law Iltutmish[1] |

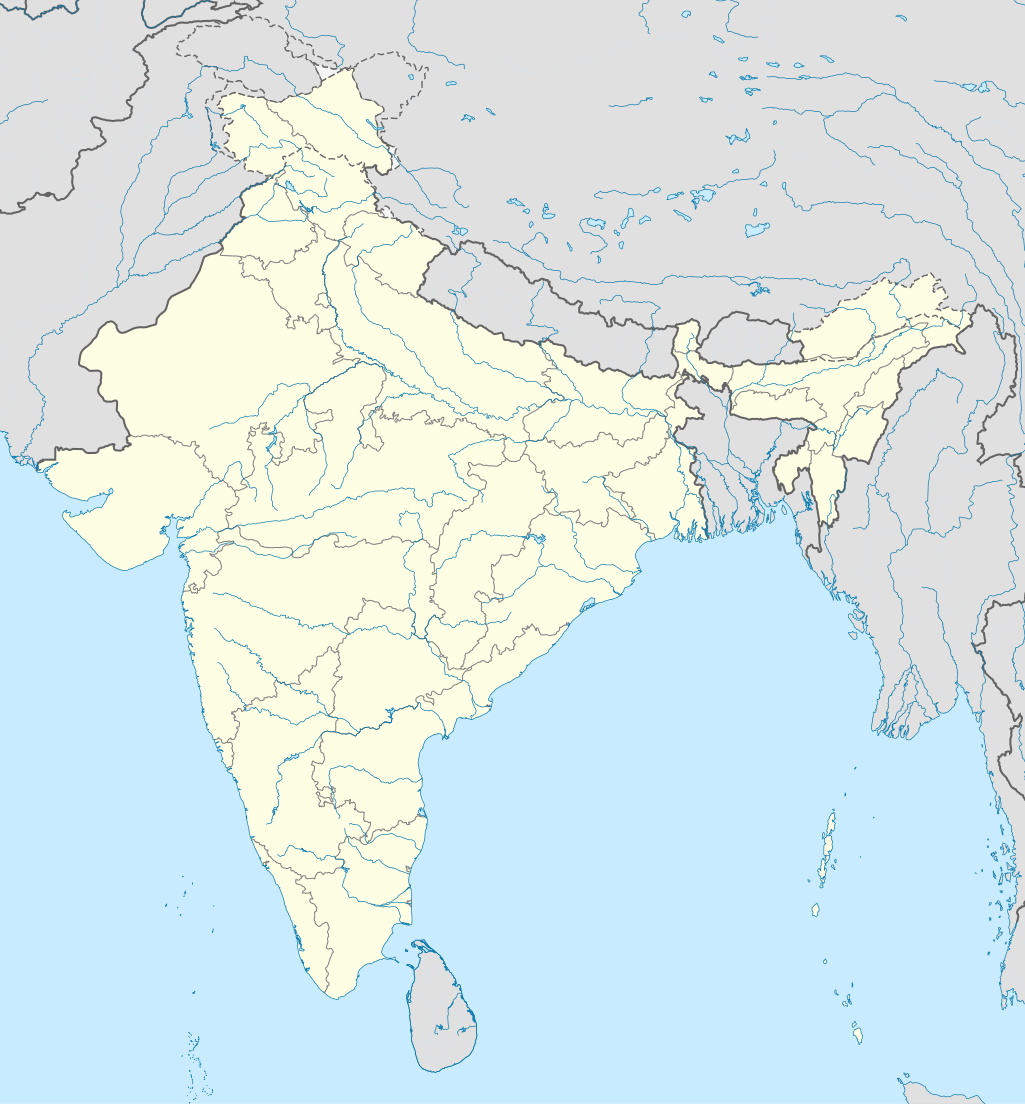

Location of Qutb Minar in India | |

Its closest comparator is the 62-metre all-brick Minaret of Jam in Afghanistan, of c.1190, a decade or so before the probable start of the Delhi tower.[7] The surfaces of both are elaborately decorated with inscriptions and geometric patterns; in Delhi the shaft is fluted with "superb stalactite bracketing under the balconies" at the top of each stage.[8] In general minarets were slow to be used in India, and are often detached from the main mosque where they exist.[9]

History

Qutubuddin Aibak, at that time a deputy of Muhammad of Ghor, but after his death founder of the Delhi Sultanate, started construction of the Qutb Minar's first storey in 1199. This level has inscriptions praising Muhammad of Ghor. Aibak's successor and son-in-law Shamsuddin Iltutmish completed a further three storeys. In 1369, a lightning strike destroyed the top storey. Firoz Shah Tughlaq replaced the damaged storey, and added one more. Sher Shah Suri also added an entrance to this tower while he was ruling and Humayun was in exile.[1]

Qutb Minar was begun after the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, which was started around 1192 by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, first ruler of the Delhi Sultanate.[6] The mosque complex is one of the earliest that survives in the Indian subcontinent.[10][11] The minaret is named after Qutb-ud-din Aibak, or Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, a Sufi saint.[12] Its ground storey was built over the ruins of the Lal Kot, the citadel of Dhillika.[11] Aibak's successor Iltutmish added three more storeys.[12]

The Minar is surrounded by several historically significant monuments of Qutb complex. The nearby pillared cupola known as "Smith's Folly" is a remnant of the tower's 19th century restoration, which included an ill-advised attempt to add some more storeys.[13][14]

The minar's topmost storey was damaged by lightning in 1369 and was rebuilt by Firuz Shah Tughlaq, who added another storey. In 1505, an earthquake damaged Qutub Minar; it was repaired by Sikander Lodi. On 1 September 1803, a major earthquake caused serious damage. Major Robert Smith of the British Indian Army renovated the tower in 1828 and installed a pillared cupola over the fifth storey, thus creating a sixth. The cupola was taken down in 1848, under instructions from The Viscount Hardinge, then Governor General of India. It was reinstalled at ground level to the east of Qutb Minar, where it remains. It is known as "Smith's Folly".[15]

Architecture

Parso-Arabic and Nagari in different sections of the Qutb Minar reveal the history of its construction, and the later restorations and repairs by Firoz Shah Tughluq (1351–89) and Sikandar Lodi[16] (1489–1990).

The tower has five superposed, stories. The lowest three comprise fluted cylindrical shafts or columns of pale red sandstone, separated by flanges and by storeyed balconies, carried on Muqarnas corbels. The fourth column is of marble, and is relatively plain. The fifth is of marble and sandstone. The flanges are a darker red sandstone throughout, and are engraved with Quranic texts and decorative elements. The whole tower contains a spiral staircase of 379 steps.[6] At the foot of the tower is the Quwat ul Islam Mosque. The minar tilts just over 65 cm from the vertical, which is considered to be within safe limits.[17]

Qutb Minar was an inspiration and prototype for many minarets and towers built. The Chand Minar and Mini Qutb Minar bear resemblance to the Qutb Minar and inspired from it.[18]

Accidents

Before 1974, the general public was not allowed access to the first floor of the minaret, via the internal staircase. Access to the top was stopped after 1000 due to suicides. On 4 December 1981, the staircase lighting failed. Between 400 and 500 visitors stampeded towards the exit, and 47 were killed by their crush and some were injured. Most of these were school children.[19] Since then, the tower has been closed to the public. Since this incident the rules regarding entry have been stringent.[20]

In literature

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poem The Qutub Minar, Delhi is a reflection on an engraving in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1833.

In popular culture

Bollywood actor and director Dev Anand wanted to shoot the song "Dil Ka Bhanwar Kare Pukar" from his film Tere Ghar Ke Samne inside the Minar. However, the cameras in that era were too big to fit inside the tower's narrow passage, and therefore the song was shot inside a replica of the Qutb Minar[21]

The site served as the Pit Stop of the second leg of the second series of The Amazing Race Australia.[22]

A picture of the minaret is featured on the travel cards and tokens issued by the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. A recently launched start-up in collaboration with the Archaeological Survey of India has made a 360o walkthrough of Qutb Minar available.[23]

Ministry of Tourism recently gave seven companies the 'Letters of Intent' for fourteen monuments under its 'Adopt a Heritage Scheme.' These companies will be the future 'Monument Mitras.' Qutb Minar has been chosen to part of that list.[24][25]

Gallery

Qutb Minar

Qutb Minar- Left to Right:Alai Darwaza, Qutb Minar, Imam Zamin's tomb

- Entrance to Minar

Calligraphy on upper-base section

Calligraphy on upper-base section Decorative motifs on upper levels

Decorative motifs on upper levels Close-up of balcony

Close-up of balcony Minar in dark views

Minar in dark views Smith's cupola (foreground)

Smith's cupola (foreground) Plaque at Minar

Plaque at Minar View through arch

View through arch Qutb Minar path view

Qutb Minar path view Old Buildings in Qutb Minar Campus

Old Buildings in Qutb Minar Campus The ancient ruins of twenty-seven Jain temple complex over which a mosque was constructed beside Qutub Minar

The ancient ruins of twenty-seven Jain temple complex over which a mosque was constructed beside Qutub Minar

Notes

- "Qutub Minar". qutubminardelhi.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "WHC list". who.unesco.org. 2009. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Singh (2010). Longman History & Civics ICSE 7. Pearson Education India. p. 42. ISBN 978-81-317-2887-1. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Harle, 424

- "Qutb Minar Height". qutubminardelhi.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Qutub Minar". Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Also two huge minarets at Ghazni.

- Yale, 164; Harle, 424 (quoted); Blair & Bloom, 149

- Harle, 429

- "Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque". qutubminardelhi.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Ali Javid; ʻAlī Jāvīd; Tabassum Javeed (1 July 2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. pp. 14, 105, 107, 130. ISBN 9780875864846. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Qutub Minar Height". qutubminardelhi.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Wright, Colin. "Ruin of Hindu pillars, Kootub temples, Delhi". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Wright, Colin. "Rao Petarah's Temple, Delhi". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Qutub Minar and Smiths Folly - an architectural disaster." Archived 7 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, WordPress.

- Plaque at Qutb Minar

- Verma, Richi (24 January 2009). "Qutb Minar tilting due to seepage: Experts". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Koch, Ebba (1991). "The Copies of the Quṭb Mīnār". Iran. 100: 95–186. doi:10.2307/4299851. JSTOR 4299851.

- "Around the World; 45 Killed in Stampede At Monument in India". The New York Times. 5 December 1981. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- Khandekar, Nivedita (4 December 2012). "31 yrs after tragedy, Qutub Minar's doors remain shut". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- Mehul S Thakkar, Mumbai Mirror 22 Nov 2011, IST (22 November 2011). "30 years later, Qutub ready to face the camera — Times of India". Articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Mehrauli Qutub Minar UNESCO World Heritage Complex Tour Guide - Destination Overview". Holiday Travel. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Qutub Minar in MEHRAULI, Delhi - 360-degree view on WoNoBo.com". Places.wonobo.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Adopt a Heritage Scheme, Qutub Minar, Delhi - to be adopted by Yatra.com". indiatoday.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Clean water to free WiFi: What Yatra.com will provide after adopting Qutub Minar". theprint.in. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

References

- Blair, Sheila, and Bloom, Jonathan M., The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800, 1995, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300064659

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- "Yale":Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, 2001, Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250, Yale University Press, ISBN 9780300088694