Crusader states

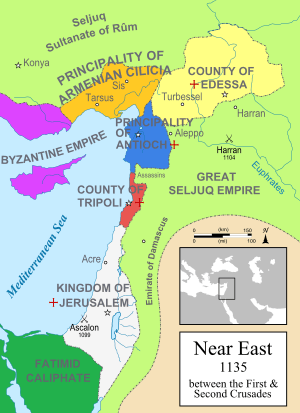

Outremer, also known as the Crusader states, were feudal Christian states in the Eastern Mediterranean. They were established at the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th century as a consequence of the First Crusade. These states in the Levant became known to historians by the French version of the phrase, Outremer. A presence remained in the region in some form until the fall of Acre in 1291 led to the rapid loss of the last remaining holdings. The crusade was proclaimed by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095. He encouraged military support for the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I against the Seljuk Turks and an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. There was an enthusiastic response in Western Europe across all social strata. This, and later campaigns, established four crusader states in the Near East: the County of Edessa; the Principality of Antioch; the Kingdom of Jerusalem; and the County of Tripoli.

The crusader states were frontier societies with a minority Frankish populations ruling indigenous populations culturally related to the neighbouring communities. The states were politically and legally stratified with the Franks controlling the relationships between self-governing and ethnically-based communities. Society was divided between Frank and non-Frank, not between Christian and Muslim. Few Franks could speak more than basic Arabic, instead relying on indigenous interpreters and headmen. Indigenous courts administered civil disputes and minor criminality with more serious offences dealt with by the Frankish cour des bourgeois or courts of the burgesses, the name of the non-noble Franks. There is little evidence of assimilation. The archaeology is culturally exclusive and written evidence indicates deep religious divisions. Large differences in status and wealth existed between urban and rural dwellers; indigenous Christians were able gain higher status and acquire wealth through commerce and industry in towns, but few Muslims lived in urban areas. Muslim and indigenous Christian populations tended to separation rather than integration. Greek Orthodox communities proved resilient with many surviving the Arab conquest, rule by the Crusaders and for centuries after the fall of the crusader states. Other indigenous communities included Palestinian Christians, Arabic speaking members of the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church and Maronite Church, Armenians as well well as Sunni, Shia and Druze Muslims.

Few artistic styles originated in the crusader states. One that did was a military architecture that demonstrated a synthesis of the European, Byzantine and Muslim traditions; with the inclusion of oriental design features such as large water reservoirs and the exclusion of occidental features like moats.[1] Early church design was in the French Romanesque style. The 12th-century rebuilding of the Holy Sepulchre retained some of the Byzantine details, but added new arches and chapels in northern French, Aquitanian and Provençal styles. In sculpture little trace of an indigenous influence remains. In contrast the visual culture demonstrates the influence of indigenous artists. Decoration of shrines, painting and the production of manuscripts and the adoption of methods from the Byzantine and indigenous artists and iconographical practice. Monumental and panel painting, mosaics and illuminations in manuscripts adopted an indigenous style. Wall mosaics were unknown in the west but were widespread in the crusader states.

Background

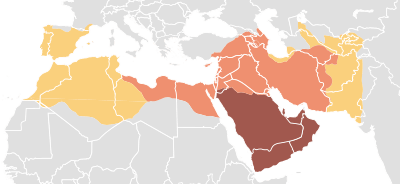

Beginning in the 7th century, following the foundation of the Islamic religion by Muhammad, and through the 8th century, Muslim Arabs under the Umayyad Caliphate captured Syria, Egypt, Iran, the Levant and North Africa from the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, and Iberia from the Visigothic Kingdom.[2] In 750 a bloody coup brought an end to Umayyad rule, leading to the gradual fragmentation of the monolithic Islamic state and the relocation of the political and economic centre of the Islamic world from Palestine to Iran and Iraq.[3] By the end of the 11th century the age of Islamic territorial expansion was long gone.[4] However, frontier conditions between the Christian and Muslim world remained militant across the Mediterranean area. From the 8th century, in what later became known as the Reconquista, Christians were campaigning in Spain. In the 11th century Norman adventurers led by Roger de Hauteville, later King Roger I of Sicily, seized Sicily from the Muslims.[5] The Eastern Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire in the early 11th century stretched east to Iran and controlled Bulgaria and much of southern Italy in the west. However, from this point the arrival of new enemies on all frontiers placed intolerable strains on the resources of both the Byzantine Empire and the neighbouring Arab Muslim regimes.[6] The situation was a serious threat to the future of the Byzantine Empire. This made the possibility of western military aid from the Papacy for specific campaigns an attractive prospect to the Byzantines.[7][8]

There were three waves of Turkic migration into the Middle East. The initial phase began in the 9th century with the use use of captured Turkic nomads as slave soldiers by the Abbasid dynasty rulers of Baghdad and others across the Middle East. These were known as ghulam or mamluks. The steppe Turks skills in horsemanship and archery were particularly valued. It was expected that these slaves would remain loyal. However, on conversion to Islam they were emancipated so there was no obstacle preventing these Turks progressing from roles as guards, as commanders, governors, dynastic founders and eventually king makers.[9] The result was Turkic dynasties in Egypt and Syria most notably the Mamluk Sultanate that destroyed the Outremer in the 13th century.[10] The second phase was led by a minor ruling clan of Oghuz Turks from Transoxania collectively known as Seljuks after the founder, Saljūq. This created a sizable ethnic Turkish presence. In the mid-11th century the Seljuks supplanted the Ghaznavids in Khurasan, extending mastery through Khurasan and into Iran all the way to Baghdad. There the Abbasid caliph granted Tughril the title Sultan, power in arabic, who was the first ruler to use this title on coinage. This ascent resulted in the Great Seljuk Empire, [11] and the House of Seljuk assimilated into Perso-arabic culture. The Empire was not centralised or a coherent whole, rather a loose assembly of provinces with differing languages and nationalities. Traditionally these were ruled as a family concern rather than by a single monarch. As such there was a tendency for fragmentation that later impacted the Seljuk resistance against the First Crusade.[12]

The first two phases of Turkic migration involved the arrival of the Turks into Arab Islamic territory and not significantly impacting the culture. The third, into Anatolia, was different as it impacted Bilād al-Rūm, the land of the Romans i.e. the Byzantine Greeks ruling what remained of the Eastern Roman Empire. Prior to the arrival of the Turks the Byzantines were on the offensive. They captured Antioch after three centuries of Arab rule and invaded Syria. Turkish Ghazi and their Byzantine equivalents, Akritai, often Turkish themselves, indulged in ephemeral cross border raiding. The Great Suljuk Sultan Alp Arslan had demonstrated no interest in push into Anatolia and there was an agreement in place to that effect. In 1071 though he interrupted campaigning in Egypt to sucure his northern borders and defeated Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at the Battle of Manzikert.[13] Historians once considered this a pivotal event but now Manzikert is regarded as only one step in the development of the Sultanate of Rum.[8] The defeat, the breakdown of that agreement, the capture of Romanos IV and the resulting collapse of the Byzantine Empire allowed the ghazi and nomadic tribesmen seeking pasture for flocks and herds to flood into the now ungoverned lands.[14]

Alp Arslan's cousin Suleiman ibn Qutulmish exploited Byzantine factionalism and carved out a new realm in Anatolia, seizing Cilicia from an Armenian warlord in 1073 and peacefully entering Antioch in 1084. Eventually, he came into conflict with the Great Seljuk Empire and was defeated and killed in 1092.[14] This formed part of a wider disintegration in the Middle East. In the same year the vizier and effective ruler of the Great Seljuk Empire, Nizam al-Mulk died closely followed by the Sultan Malik-Shah and the Fatimid khalif, Al-Mustansir Billah. The Islamic historian Carole Hillenbrand has described this as analogous to the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 with the phrase "familiar political entities gave way to disorientation and disunity".[15] The confusion and division meant the Islamic world disregarded the world beyond; this made it vulnerable to, and surprised by, the First Crusade.[16]

Another ghazi state was founded at the time as the Sultanate of Rum, in north and central Anatolia by someone known by the Persian honourific Danishmend Gazi. His son, Gazi Gümüshtigin, captured Bohemond I of Antioch and in alliance with Suleiman's son Kilij Arslan defeated two crusading contingents in 1100.[17]

In 1095 the Byzantine emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, requested military support from the Council of Piacenza for the fight with the Turks. Later that year, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban supported this and exhorted war.[18] This prompted a popular outbreak amongst poor Christians, led by the French priest Peter the Hermit, known as the People's Crusade. Passing through Germany they indulged in wide-ranging anti-Jewish activities and massacres. On leaving Byzantine-controlled territory in Anatolia they were annihilated in a Turkish ambush at the Battle of Civetot in October 1096.[19] They were followed by a feudal army that may have numbered 100,000 including non-combatant that was cautiously welcomed to Byzantium by Alexios late in 1096.[20] He made them promise to return all recovered Byzantine territory[21] These promises were not kept, for example Bohemond I of Antioch retained Antioch when it was captured, rather than returning it and fought with the Byzantines for a decade until his failure in Italy at the Siege of Dyrrhachium (1107–1108).[22][23]

After the First Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon was left with only 300 knights and 2,000 infantry to defend the territory won in the Eastern Mediterranean. Of the crusader princes only Tancred remained, with the aim of establishing his own lordship.[24] At this point the Franks, as the western European crusaders were commonly known, held only Jerusalem, Antioch and Edessa but not the surrounding country. Jerusalem remained economically sterile, despite the advantages of being the centre of administration for church and state and benefiting from streams of pilgrims.[25] Consolidation in the first half of the 12th-century established four crusader states:

- The County of Edessa (1098–1149)[26]

- The Principality of Antioch (1098–1268).[27] Antioch survived despite repeated defeats, and the death or captivity of its leaders: in 1100 Prince Bohemond was captured by the Danishmends; in 1104 Bohemond and Tancred fled the defeat of the forces of Edessa and Antioch at Harran; in 1119 regent Roger of Salerno was killed at the Field of Blood fighting a force from Alleppo; in 1130 Bohemond II was killed fighting the Danishmends; in 1149 Prince Raymond was killed by the forces of Nur ad-Din at Inab. Nur-ad-Din sent Raymond's head as a gift to the Caliph of Baghdad; in 1161 Prince Raynald was captured while raiding and held in captivity for fifteen years.[28][29]

- The Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded in 1099, lasted until 1291,[30] when the city of Acre fell.[31] During the first kingdom the Kings of Jerusalem regularly came to the aid of the other states. This became dynastic when two of Baldwin II of Jerusalem's daughters married into the families ruling Antioch and Tripoli. The history of Jerusalem is divided into three eras: firstly, one of expansion into Syria until the 1140s; secondly, competition with Nur ad-Din until the 1170s including the failures of the Second Crusade and Amalric's invasion of the Nile region; finally decay, defeat by Saladin at Hattin in 1187 and the loss of the majority of the kingdom's territory. The monarchy was unstable with open succession disputes in 1100, 1118, 1163 and 1186 with civil unrest in 1134–34, 1152 and 1186. Baldwin II was one of the Franks who spent time in Muslim captivity, a year between 1123 and 1124.[32]

- The County of Tripoli (1104–1289, although the city of Tripoli itself remained in Muslim control until 1109).[33] The county had little territory but managed to retain its autonomy from the 1120s. in 1152 Raymond II was assassinated. For ten years from 1164 Raymond II was captive after defeat to Nur-ad-Din at Harim. In this time his cousin, Amalric of Jerusalem acted as regent.[28]

Demography

Modern research based on historical geography techniques indicate that Muslims and indigenous Christian populations integrated less than had been previously thought. Palestinian Christians lived around Jerusalem and in an arc stretching from Jericho and the Jordan to Hebron in the south.[34] Comparing archaeological research on Byzantine churches built before the Muslim conquest and Ottoman census records from the 16th century demonstrates that some Greek Orthodox communities had disappeared before the crusades but most continued for centuries after the fall of the crusader states. Maronites were concentrated in Tripoli; Jacobites in Antioch and Edessa. Armenians were concentrated in the north but communities existed in all major towns. Palestine's central areas had a Muslim majority population. The Muslims were mainly Sunnis, but Shi'ite communities existed in Galilee. The nonconformist Muslim Druzes were recorded living in the mountains of Tripoli. The Jewish population resided in coastal towns and some Galilean villages.[35][36]

With the capture of Jerusalem and victory at Ascalon the majority of the crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe.[37] The Frankish population of the Kingdom of Jerusalem became concentrated in three major cities. By the 13th century the population of Acre probably exceeded 60,000, then came Tyre, with the capital being the smallest of the three with a population somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000.[38] At its zenith, the Latin population of the region reached c. 250,000 with the Kingdom of Jerusalem's population numbering c. 120,000 and the combined total in Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa being broadly comparable.[39] The presence of Frankish peasants is evident in 235 villages, out of a total of some 1,200 rural settlements.[40]

In context, Josiah Russell estimates the population of what he calls "Islamic territory" as roughly 12.5 million in 1000—Anatolia 8 million, Syria 2 million, Egypt 1.5 million and North Africa 1 million — with the European areas that provided crusaders having a population of 23.7 million. He estimates that by 1200 that these figures had risen to 13.7 million in Islamic territory—Anatolia 7 million, Syria 2.7 million, Egypt 2.5 million and North Africa 1.5 million— while the crusaders' home countries population was 35.6 million. Russell acknowledges that much of Anatolia was Christian or under the Byzantines and that some purportedly Islamic areas such as Mosul and Baghdad had significant Christian populations.[41]

Society

Outremer was frontier society with a Frankish elite ruling an indigenous population related to the neighbouring communities, many of whom were hostile to the Franks.[42] It was politically and legally stratified, with self-governing, ethnically-based communities. Relations between communities were controlled by the Franks.[43] The basic division in society was between Frank and non-Frank, and not between Christian and Muslim. All Franks were considered free men, while the indigenous peoples lived like western serfs. Conversion to Latin Christianity was their only route to full citizenship. The Franks imposed officials in order to use the military, legal and administrative systems to control the indigenous peoples. Few Franks could speak more than basic Arabic. Dragomans—interpreters—and ruʾasāʾ—village headmen—were used as mediators. Civil disputes and minor criminality were administered by the courts of the indigenous communities, but more serious offences and cases involving Franks were dealt with by the Frankish cour des bourgeois or courts of the burgesses, the name given to the non-noble Franks.[44] The lack of material evidence makes it difficult to identify the level of assimilation. The archaeology is culturally exclusive and written evidence indicates deep religious division, although some historians assume that Outremer's heterogeneity eroded formal apartheid.[45] The key differentiator in status and economic position was between urban and rural dwellers. Indigenous Christians could gain higher status and acquire wealth through commerce and industry in towns, but few Muslims lived in urban areas except those in servitude.[46]

Frankish courts reflected the region's diversity. Queen Melisende was part Armenian and married Fulk from Anjou. Their son Amalric, first married a Frank from the Levant, then a Byzantine Greek. William of Tyre was appalled at the use of Jewish, Syrian and Muslim physicians, who were popular among the nobility. Greek and Arabic speaking Christians made Antioch a centre of cultural interchange. The indigenous peoples showed the Frankish nobility traditional deference. Some Franks adopted the their dress, food, housing and military techniques. This does not mean that Outremer was a cultural melting pot. Inter-communal relations were shallow, separate identities were maintained and other communities were considered alien.[47]

Economy

In addition to being economic centres themselves, the crusader states provided an obstacle to Muslim trade by sea with the west and to the land routes from Mesopotamia and Syria to the great urban economies of the Nile. Despite hostility, commerce continued, coastal cities remained maritime outlets for the Islamic hinterland and eastern wares were exported to Europe in unprecedented volumes. The Byzantine-Muslim mercantile growth in the 12th and 13th centuries may have occurred anyway, as the Western European economy was booming due to population growth; this increased wealth and created a growing social class demanding city centred products and eastern imports, but it is likely that the Crusades hastened the developments. European fleets were expanded, better ships built, navigation improved and fare paying pilgrims subsidised many voyages. Agricultural production, largely the domain of the indigenous population, flourished before the fall of the First Kingdom in 1187, but was negligible afterwards. Franks, Muslims, Jews and indigenous Christians traded crafts in the souks, teeming oriental bazaars, of the cities.[48] The Italian, Provençal and Catalan merchants monopolised shipping, imports, exports, transportation and banking. The Frankish noble and ecclesiastical institutional income was based on income from estates, market tolls and taxation.[49] The main centres of production were Antioch, Tripoli, Tyre and, less importantly, Beirut. Textiles, glass, dyestuffs, olives, wine, sesame oil and sugar were exported; silk was particularly prized.[50] The Frankish population, estimated at roughly a quarter of a million people, provided an import market for clothing and finished goods.[51]

Coinage

The Franks adopted the more monetised indigenous economic system, using a hybrid coinage: predominantly northern Italian and southern French silver European coins; Frankish variant copper coins minted in Arabic and Byzantine styles; and silver and gold dirhams and dinars. After 1124, Egyptian dinars were copied, creating Jerusalem's gold bezant. Following the collapse of Outremer in 1187, trade, rather than agriculture, increasingly dominated the economy and western coins began dominating the coinage in circulation. Although lords in Tyre, Sidon and Beirut minted silver pennies and copper coins there is little evidence of systematic attempts to create a unified currency.[52]

Monarchy

During the period of near constant warfare in the early decades of the 12th century, the king of Jerusalem's foremost role was leader of the feudal host. They very rarely awarded land or lordships, and those awarded that became vacant—a frequent event due to the high mortality rate in the conflict—reverted to the crown. Instead their followers' loyalty was rewarded with city incomes. As a result, the royal domain of the first five rulers —including much of Judea, Samaria, the coast from Jaffa to Ascalon, the ports of Acre and Tyre, and other scattered castles and territories—was larger that the combined holdings of the nobility. This meant that the rulers of Jerusalem had greater internal power than comparative western monarchs, although they did not have the necessary administrative systems and personnel to govern such a large realm.[53]

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as Raynald of Châtillon, Lord of Oultrejordain, and Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, Prince of Galilee—often acted as autonomous rulers. Royal powers were abrogated and effectively governance was undertaken within the feudatories. What central control remained was exercised at the Haute Cour—High Court, in English. Only the 13th century jurists of Jerusalem used this term, curia regis was more common in Europe. These were meetings between the king and his tenants in chief. Over time the duty of the vassal to give counsel developed into a privilege and ultimately the legitimacy of the monarch depended on the agreement of the court.[54] The barons of Jerusalem in the 13th century have been poorly regarded by both contemporary and modern commentators: James of Vitry was disgusted by their superficial rhetoric; the historian Jonathan Riley-Smith writes of their pedantry and the use of spurious legal justification for political action.[55]

In practice, the High Court consisted of the great barons and the king's direct vassals. In law a quorum was the king and three tenants in chief. The 1162 assise sur la ligece theoretically expanded the court's membership to all 600 or more fief-holders, making them all peers. All those who paid homage directly to the king were now members of the Haute Cour of Jerusalem. They were joined by the heads of the military orders by the end of the 12th century, and the Italian communes in the 13th century.[56] Before the defeat at Hattin in 1187 the laws developed by the court were documented as assises in Letters of the Holy Sepulchre.[57] The entire body of written law was lost in the subsequent fall of Jerusalem. From this point the legal system was largely based on custom and the memory of the lost legislation. The renowned jurist Philip of Novara lamented "We know [the laws] rather poorly, for they are known by hearsay and usage...and we think an assize is something we have seen as an assize...in the kingdom of Jerusalem [the barons] made much better use of the laws and acted on them more surely before the land was lost". Thus a myth was created of an idyllic early 12th century legal system. The barons used this to reinterpret the assise sur la ligece, which Almalric I intended to strengthen the crown, to instead constrain the monarch, particularly with regards to the right of the monarch to remove feudal fiefs without trial. The concomitant loss of the vast majority of rural fiefs led to the barons becoming an urban mercantile class where knowledge of the law was a valuable, well-regarded skill and a career path to higher status.[58]

The leaders of the Third Crusade ignored the monarchy of Jerusalem; the kings of England and France agreed on the division of future conquests as if there was no need to take into account the nobility of the crusader states. The historian Joshua Prawer considered that the weakness of the crown of Jerusalem was demonstrated by the rapid offering of the throne to Conrad of Montferrat in 1190 and then Henry II, Count of Champagne in 1192.[59] Emperor Frederick II married Queen Isabella in 1225 and immediately claimed the throne of Jerusalem from her father, the King Regent, John of Brienne. In 1228 Isabella died after giving birth to a son, Conrad, who through his mother was now legally king of Jerusalem and Frederick's heir.[60] From 1229 when Frederick II left the Holy Land to defend his Italian and German lands, monarchs were absent—Conrad from 1225 until 1254, his son Conradin until his execution by Charles of Anjou in 1268. Government in Jerusalem had developed in the opposite direction to monarchies in the west. St Louis, Emperor Frederick and Kind Edward I—contemporary rulers of France, Germany and England respectively— were powerful, with centralised bureaucracies. Jerusalem had a royalty without power.[61] Magnates such as the Ibelins attempted to seize the regency, fighting for control with an Italian army led by Frederick's viceroy Richard Filangieri in the War of the Lombards. Tyre, the Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights and Pisa supported Filangieri. In opposition were the Ibelins, Acre, the Templars and Genoa. The rebels established a surragate commune, or parliament, for twelve years in Acre.[62] They prevailed in 1242 with the capture of Tyre and a succession of Ibelin and Cypriot regents followed.[63] Centralised government collapsed while the nobility, military orders and Italian communes took the lead. Three Cypriot Lusignan kings succeeded without the financial or military resources to recover the lost territory. The title of king was even sold to Charles of Anjou, but although he gained power for a short while, he never visited the kingdom. The king of Cyprus fought at Acre until all hope was lost and then returned to his island realm.[64] Cyprus survived the fall of the mainland crusader states and Peter I of Cyprus launched the last crusade against Egypt that temporarily captured Alexandria in 1365.[65]

Religion

Partly a result of anti-Orthodox sentiment the early crusaders filled ecclesiastical positions in the Orthodox church left vacant with Franks, including the patriarchy of Jerusalem when Simeon II died. The Greek Orthodox Church was considered part of the universal Church, which enabled the replacement of Orthodox bishops by Latin clerics in coastal towns. The first Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Arnulf of Chocques, ejected the Greek Orthodox monks from the Holy Sepulchre but relented when the miracle of Easter Fire failed in their absence. The appointment of Latin bishops had little effect on the Arabic-speaking Orthodox Christians because the previous bishops were also foreign, from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin bishops used Greeks as coadjutor bishops to administer Syrians and Greeks left without higher clergy. In many villages Latin and Orthodox Christians shared a church. In exceptional political circumstances, Greeks replaced Latin patriarchs in Antioch. Orthodox monasteries were rebuilt and Orthodox monastic life revived. This toleration continued despite an increasingly interventionist papal reaction demonstrated by Jacques de Vitry, Bishop of Acre. The Armenians, Copts, Jacobites, Nestorians and Maronites had greater autonomy. As they were not in communion with Rome they could retain their own bishops without a conflict of authority. Around 1181 Aimery of Limoges, Patriarch of Antioch, managed to bring the Maronites into communion with Rome, establishing a precedent for the Uniate Churches.[66]

That religion prevented assimilation is evidenced by the Franks' discriminatory laws against Jews and Muslims. They were banned from living in Jerusalem and sexual relations between Muslims and Christians were punished by mutilation. Some mosques were converted into Christian churches, but the Franks did not force Muslims to convert to Christianity. Frankish lords were particularly reluctant, because conversion would have ended the Muslim peasants' servile status. The Muslims were permitted to pray in public and their pilgrimages to Mecca continued.[67] The Samaritans' annual Passover festival attracted visitors from beyond the kingdom's borders.[68]

Communes

Largely located in the ports of Acre, Tyre, Tripoli and Sidon, communes of Italians, Provençals and Catalans had distinct cultural characteristics and exerted significant political power. Separate from the Frankish nobles or burgesses, the communes were autonomous political entities closely linked to their towns of origin. This gave them the ability to monopolise foreign trade and almost all banking and shipping in Outremer. Their parent cities' naval support was essential for the crusader states. Every opportunity to extend trade privileges was taken. One example saw the Venetians receiving one-third of Tyre and its territories, and exemption from all taxes, after Venice participated in the successful 1124 siege of the city. Despite all efforts, the Syrian and Palestinian ports were unable to replace Alexandria and Constantinople as the primary centres of commerce in the region. Instead, the communes competed with the monarchs and each other to maintain economic advantage. Power derived from the support of the communards' home cities rather than their number, which never reached more than hundreds. Thus, by the middle of the 13th century, the rulers of the communes were barely required to recognise the authority of the crusaders and divided Acre into several fortified miniature republics.[69][70]

Military orders

The crusaders habitually followed the customs of their Western European homelands and there were very few cultural innovations in the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this were the military orders, warfare and fortifications.[71] The order of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, more commonly known as the Templars, was formed in 1119 with a mission to protect pilgrims in the perilous territory. The founders were a group of knights attached to the Holy Sepulchre. They were formally recognised at the Council of Nablus and eventually granted the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount to use as the orders headquarters. This was known to the Franks as Solomon's Temple from which the order's name derives. The founding leaders, Hugues de Payens and Godfrey de Saint-Omer travelled to Europe and in 1129 the order was recognised by the Latin Church at the Council of Troyes. Support, privileges and immunities followed from the papacy.[72] Donations of estates across Western Europe and the Levant enabled the order to provide the crusader states with troops, funding, loans and luxury accommodation for travellers.[73]

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem were more commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller. The order began with the operation of an Amalfi funded pilgrim hospital in Jerusalem during the 1080s. Soon after the first crusades they started receiving generous donations both locally and in the west. In 1113 the order that moved from a lay organisation to a religious one was recognised by the pope. It grew into an enormous concern with extensive estates in Italy, Catalonia and Southern France. The income from these provided funding for hundreds of beds serving patients from all religions and genders. By 1126 a military dimension had been added and members formed part of the army from Jerusalem that attacked Damascus.[74]

The creation of communities of warrior monks united the two medieval ideals of monasticism and knighthood.[75] During the 12th and 13th centuries the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar developed into Latin Christendom's first professional armies. They were now supranational organisations with autonomous powers in the region.[76] The template presented by these two organisations led to the formation of further orders. These stretched as far as the Iberian Peninsula and Christendom's northern borders. Notable examples were the Order of Saint Lazarus, founded in 1130, for knights with leprosy and in 1190 the Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem. This is more commonly known as the Teutonic Order. By 1180 the number of castles controlled and the 700 knights that the military orders could put in the field matched that from all other sources available to the kingdom of Jerusalem. The knightly elite was also supported by massive organisations of sergeants, clerics, layman and servants.[77]

Art and architecture

According to Joshua Prawer no major European poet, theologian, scholar or historian settled in the crusader states. Some went on pilgrimage, and this is reflected in new imagery and ideas in western poetry. Although they did not migrate east themselves, their output often encouraged others to journey on pilgrimage to the east.[78]

Historians consider military architecture—demonstrating a synthesis of the European, Byzantine and Muslim traditions—the most original and impressive artistic achievement of the crusades. Castles were a tangible symbol of the dominance of a Latin Christian minority over a largely hostile majority population. They also acted as centres of administration.[79] Modern historiography rejects the 19th-century consensus that Westerners learnt the basis of military architecture from the Near East, as Europe had already experienced rapid growth in defensive technology before the First Crusade. Direct contact with Arab fortifications originally constructed by the Byzantines did influence developments in the east. But the lack of documentary evidence means that it remains difficult to differentiate between the importance of this design culture and the constraints of situation, which led to the inclusion of oriental design features such as large water reservoirs and the exclusion of occidental features like moats.[1]

Typically, early church design was in the French Romanesque style. This can be seen in the 12th-century rebuilding of the Holy Sepulchre. It retained some of the earlier Byzantine details, but new arches and chapels were built to northern French, Aquitanian and Provençal patterns. There is little trace of any surviving indigenous influence in sculpture, although in the Holy Sepulchre the column capitals of the south facade follow classical Syrian patterns.[80]

In contrast to architecture and sculpture, it is in the area of visual culture that the assimilated nature of the society was demonstrated. Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries the influence of indigenous artists was demonstrated in the decoration of shrines, painting and the production of manuscripts. In addition, Frankish practitioners borrowed methods from the Byzantines and indigenous artists and iconographical practice. Monumental and panel painting, mosaics and illuminations in manuscripts adopted an indigenous style leading to a cultural synthesis illustrated by the Church of the Nativity. Wall mosaics were unknown in the west but in widespread use in the crusader states. Whether this was by indigenous craftsmen or learnt by Frankish ones is unknown, but a distinctive and original artistic style evolved.[81]

Manuscripts were produced and illustrated in workshops housing Italian, French, English and indigenous craftsmen leading to a cross-fertilisation of ideas and techniques. An example of this is the Melisende Psalter, created by several hands in a workshop attached to the Holy Sepulchre. This style could have either reflected or influenced the taste of patrons of the arts. But what is seen is an increase in stylised Byzantine-influenced content. This even extended to the production of icons, unknown at the time to the Franks, sometimes in a Frankish style and even of western saints. This is seen as the origin of Italian panel painting.[82] While it is difficult to track illumination of manuscripts and castle design back to their sources, textual sources are simpler. The translations made in Antioch are notable, but they are considered of secondary importance to the works emanating from Muslim Spain and from the hybrid culture of Sicily.[83]

Military

Reports from John of Ibelin indicate that around 1170 the military force of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was based on a feudal host of about 647 to 675 heavily armoured knights. Each feudatory would also provide his own armed retainers. Non-noble light cavalry and infantry were known as serjants. The prelates and the towns were to provide 5,025 serjants to the royal army, according to Ibelin's list. This force would be augmented by hired soldiery called Turcopoles. In times of emergency, the king could also call upon a general muster of the whole Christian population.[84]

Joshua Prawer estimated that the military orders could match the king's fighting strength. This means the total military of the kingdom was approximately 1,200 knights and 10,000 serjants. Enough for further territorial gains, but fewer than required to maintain military domination. This was also a problem defensively. Putting a major army into the field required draining castles and cities of able-bodied fighting men. In the case of a defeat, such as the Battle of Hattin, there remained few to resist the invaders. Muslim armies were incohesive and seldom campaigned outside the period between sowing and harvest. As a result, the crusaders adopted delaying tactics when faced with a superior invading Muslim force. They would avoid direct confrontation, instead retreating to strongholds and waiting for the Muslim army to disperse. It took generations before the Muslims recognised that they could not conquer Outremer without destroying the Franks' fortresses. This strategic change forced the crusaders away from the tactic of gaining and holding territory, including Jerusalem. Instead their aim became to attack and destroy Egypt. By removing this constant regional challenge, the crusaders hoped to gain the necessary time to improve the kingdom's demographic weakness. Egypt was isolated from the other Islamic power centres, it would be easier to defend and was self-sufficient in food.[85]

Little was achieved by a Fifth Crusade, primarily raised from Hungary, Germany, Flanders and led by King Andrew II of Hungary and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria. The crusaders attacked Egypt to break the Muslim hold on Jerusalem. Damietta was captured but then returned and an eight-year truce agreed after the Franks advancing into Egypt surrendered.[86] In 1249 Louis IX led a crusade attacking Egypt, was defeated at the Battle of Al Mansurah and the crusaders were captured as they retreated. Louis and his nobles were ransomed, other prisoners were given a choice of conversion to Islam or beheading. A ten-year truce was established and Louis remained in Syria until 1254 consolidating the Frankish position.[87][88]

Language

The Franks ruled as an elite and outnumbered class. As such, linguistic differences remained a key differentiator between the Franks lords and the local population. The Franks typically spoke Old French and wrote in Latin. While some learnt Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Syriac and Hebrew this was unusual.[89]

Legacy

After the fall of Acre the Hospitallers first relocated to Cyprus. The order conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798). The Sovereign Military Order of Malta survives to the present-day. King Philip IV of France probably had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led to him exerting pressure on Pope Clement V. The pope responded in 1312 dissolving the order on the alleged and probably false grounds of sodomy, magic and heresy.[90]

The raising, transportation, and supply of large armies led to flourishing trade between Europe and the crusader states. The Italian city-states of Genoa and Venice flourished, through profitable trading communes.[91][92] Many historians argue that the interaction between the western Christian and Islamic cultures played a significant, ultimately positive, part in the development of European civilisation and the Renaissance.[93] Relations between Europeans and the Islamic world, stretching across the length of the Mediterranean Sea, led to an improved perception of Islamic culture in the West. But this broad area of interaction also makes it difficult for historians to identify how much of this cultural cross-fertilisation originated in the crusader states and how much originated in Sicily and Spain.[83]

References

- Prawer 1972, pp. 295–296.

- Tyerman 2006, pp. 51–54.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 18.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 40.

- Mayer 1988, pp. 17–18.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 42–46.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 46.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 27.

- Findley 2005, pp. 65–68.

- Holt 1986, pp. 6–7.

- Findley 2005, pp. 68–69.

- Holt 1986, p. 11.

- Holt 1986, pp. 167–168.

- Holt 1986, p. 168.

- Hillenbrand 1999, p. 33.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 41.

- Holt 1986, p. 169.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 30.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 41.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 43–48.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 50–61.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 72–82.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 142–149.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 106.

- Prawer 1972, p. 87.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 60–61.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 82–88.

- Tyerman 2019, p. 123.

- Lock 2006, pp. 25, 27, 34, 40, 50, 55.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 103–104.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 651–656.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 118–126.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 147–50.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 131.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 131–132.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 49,51.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 104–106.

- Prawer 1972, p. 82.

- Prawer 1972, p. 396.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 150.

- Russell 1985, p. 298.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 17–19.

- Tyerman 2019, p. 127.

- Prawer 1972, p. 81.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 126–136.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 128–130.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 127,131,136–141.

- Prawer 1972, p. 382.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 352–354.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 392–393.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 396–397.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 120–121.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 104–105.

- Prawer 1972, p. 112.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 226.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 112–117.

- Prawer 1972, p. 122.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 228.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 107–108.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 563–571.

- Prawer 1972, p. 104.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 229.

- Tyerman 2019, p. 268.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 108–109.

- Tyerman 2019, p. 392.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 134–143.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 127–129.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 131–132.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 85–93.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 151–152.

- Prawer 1972, p. 252.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 168.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 153–154.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 154–155.

- Prawer 1972, p. 253.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 168–170.

- Tyerman 2019, p. 156.

- Prawer 1972, p. 468.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 280–281.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 146.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 145–146.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 147–149.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 667–668.

- Jotischky 2004, p. 134.

- Prawer 1972, pp. 327–333, 340–341.

- Jotischky 2004, pp. 214–218,236.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 583–607,615–620.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 276–277.

- Asbridge 2012, p. 177.

- Davies 1997, p. 359.

- Housley 2006, pp. 152–154.

- Davies 1997, pp. 359–360.

- Nicholson 2004, p. 96.

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Norman (1997). Europe: A History. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6633-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Findley, Carter Vaughan (2005). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516770-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hillenbrand, Carole (1999). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0630-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (1986). The Age Of The Crusades-The Near East from the eleventh century to 1517. Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-0-58249-302-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1189-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1988). The Crusades ( Second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873097-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-582-41851-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicholson, Helen (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prawer, Joshua (1972). The Crusaders' Kingdom. Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-224-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Russell, Josiah C. (1985). "The Population of the Crusader States". In Zacour, Norman P.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades. 5 The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 295–314. ISBN 0-299-09140-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tyerman, Christopher (2019). The World of the Crusades. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21739-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Andrew D Buck, "Settlement, Identity, and Memory in the Latin East: An Examination of the Term ‘Crusader States’." The English Historical Review

- Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174–1277. The Macmillan Press, 1973.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crusader states. |