Ocean sunfish

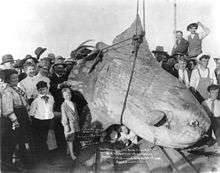

The ocean sunfish or common mola (Mola mola) is one of the heaviest known bony fishes in the world. Adults typically weigh between 247 and 1,000 kg (545–2,205 lb). The species is native to tropical and temperate waters around the world. It resembles a fish head with a tail, and its main body is flattened laterally. Sunfish can be as tall as they are long when their dorsal and ventral fins are extended.

| Ocean sunfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Tetraodontiformes |

| Family: | Molidae |

| Genus: | Mola |

| Species: | M. mola |

| Binomial name | |

| Mola mola | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Orthragoriscus elegans Ranzani, 1839 | |

Sunfish are generalist predators that consume largely small fishes, fish larvae, squid, and crustaceans. Sea jellies and salps, once thought to be the primary prey of sunfish, make up only 15% of a sunfish's diet. Females of the species can produce more eggs than any other known vertebrate,[3] up to 300,000,000 at a time.[4] Sunfish fry resemble miniature pufferfish, with large pectoral fins, a tail fin, and body spines uncharacteristic of adult sunfish.

Adult sunfish are vulnerable to few natural predators, but sea lions, killer whales, and sharks will consume them. Among humans, sunfish are considered a delicacy in some parts of the world, including Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. In the EU, regulations ban the sale of fish and fishery products derived from the family Molidae.[5] Sunfish are frequently caught in gillnets.

A member of the order Tetraodontiformes, which also includes pufferfish, porcupinefish, and filefish, the sunfish shares many traits common to members of this order. The ocean sunfish, Mola mola, is the type species of the genus.

Naming and taxonomy

Many of the sunfish's various names allude to its flattened shape. Its specific name, mola, is Latin for "millstone", which the fish resembles because of its gray color, rough texture, and rounded body. Its common English name, sunfish, refers to the animal's habit of sunbathing at the surface of the water. The Dutch-, Portuguese-, French-, Catalan-, Spanish-, Italian-, Russian-, Greek- and German-language names, respectively maanvis, peixe lua, poisson lune, peix lluna, pez luna, pesce luna, рыба-луна, φεγγαρόψαρο and Mondfisch, mean "moon fish", in reference to its rounded shape. In German, the fish is also known as Schwimmender Kopf, or "swimming head". In Polish, it is named samogłów, meaning "head alone", because it has no true tail. In Swedish, Danish and Norwegian it is known as klumpfisk, in Dutch klompvis, in Finnish möhkäkala, all of which meaning "lump fish". The Chinese translation of its academic name is fān chē yú 翻車魚, meaning "toppled wheel fish". The ocean sunfish has various superseded binomial synonyms, and was originally classified in the pufferfish genus, as Tetraodon mola.[6][7] It is now placed in its own genus, Mola, with three species: Mola mola, Mola tecta (hoodwinker sunfish) [8] and Mola alexandrini. The ocean sunfish, Mola mola, is the type species of the genus.[9]

The genus Mola belongs to the family Molidae. This family comprises three genera: Masturus, Mola and Ranzania. The common name "sunfish" without qualifier is used to describe the marine family Molidae as well as the freshwater sunfish in the family Centrarchidae which are unrelated to Molidae. On the other hand, the name "ocean sunfish" and "mola" refer only to the family Molidae.[3]

The family Molidae belongs to the order Tetraodontiformes, which includes pufferfish, porcupinefish, and filefish. It shares many traits common to members of this order, including the four fused teeth that form the characteristic beak and give the order its name (tetra=four, odous=tooth, and forma=shape). Indeed, sunfish fry resemble spiky pufferfish more than they resemble adult molas.[10]

Description

The caudal fin of the ocean sunfish is replaced by a rounded clavus, creating the body's distinct truncated shape. The body is flattened laterally, giving it a long oval shape when seen head-on. The pectoral fins are small and fan-shaped, while the dorsal fin and the anal fin are lengthened, often making the fish as tall as it is long. Specimens up to 3.3 m (10.8 ft) in height have been recorded.[11]

The mature ocean sunfish has an average length of 1.8 m (5.9 ft) and a fin-to-fin length of 2.5 m (8.2 ft). The weight of mature specimens can range from 247 to 1,000 kg (545 to 2,205 lb),[3][12][13] but even larger individuals are not unheard of. The maximum size is up to 3.3 m (10.8 ft) in length,[11][14] 4.2 m (14 ft) across the fins,[15] and up to 2,300 kg (5,100 lb) in mass.[16]

The spinal column of M. mola contains fewer vertebrae and is shorter in relation to the body than that of any other fish.[17] Although the sunfish descended from bony ancestors, its skeleton contains largely cartilaginous tissues, which are lighter than bone, allowing it to grow to sizes impractical for other bony fishes.[17][18] Its teeth are fused into a beak-like structure,[16] and it has pharyngeal teeth located in the throat.[19]

The sunfish lacks a swim bladder.[17] Some sources indicate the internal organs contain a concentrated neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin, like the organs of other poisonous tetraodontiformes,[16] while others dispute this claim.[20]

Fins

In the course of its evolution, the caudal fin (tail) of the sunfish disappeared, to be replaced by a lumpy pseudotail, the clavus. This structure is formed by the convergence of the dorsal and anal fins,[21][22] and is used by the fish as a rudder.[23] The smooth-denticled clavus retains 12 fin rays, and terminates in a number of rounded ossicles.[24]

Ocean sunfish often swim near the surface, and their protruding dorsal fins are sometimes mistaken for those of sharks.[25] However, the two can be distinguished by the motion of the fin. Sharks, like most fish, swim by moving the tail sideways while keeping the dorsal fin stationary. The sunfish, though, swings its dorsal fin and anal fin in a characteristic sculling motion.[26]

Skin

Adult sunfish range from brown to silvery-grey or white, with a variety of mottled skin patterns; some of these patterns may be region-specific.[3] Coloration is often darker on the dorsal surface, fading to a lighter shade ventrally as a form of countershading camouflage. M. mola also exhibits the ability to vary skin coloration from light to dark, especially when under attack.[3] The skin, which contains large amounts of reticulated collagen, can be up to 7.3 cm (2.9 in) thick on the ventral surface, and is covered by denticles and a layer of mucus instead of scales. The skin on the clavus is smoother than that on the body, where it can be as rough as sandpaper.[17]

More than 40 species of parasites may reside on the skin and internally, motivating the fish to seek relief in a number of ways.[3][24] One of the most frequent ocean sunfish parasites is the flatworm Accacoelium contortum.[27]

In temperate regions, drifting kelp fields harbor cleaner wrasses and other fish which remove parasites from the skin of visiting sunfish. In the tropics, M. mola solicits cleaning help from reef fishes. By basking on its side at the surface, the sunfish also allows seabirds to feed on parasites from its skin. Sunfish have been reported to breach, clearing the surface by approximately 3 m (10 ft), in an apparent effort to dislodge embedded parasites.[25][28]

Range and behavior

Ocean sunfish are native to the temperate and tropical waters of every ocean in the world.[17] Mola genotypes appear to vary widely between the Atlantic and Pacific, but genetic differences between individuals in the Northern and Southern hemispheres are minimal.[29]

Although early research suggested sunfish moved around mainly by drifting with ocean currents, individuals have been recorded swimming 26 km (16 mi) in a day at a cruising speed of 3.2 km/h (2.0 mph).[23] Sunfish are pelagic and swim at depths to 600 m (2,000 ft). They are also capable of moving rapidly when feeding or avoiding predators, to the extent they can vertically leap out of water. Contrary to the perception that sunfish spend much of their time basking at the surface, M. mola adults actually spend a large portion of their lives actively hunting at depths greater than 200 m (660 ft), occupying both the epipelagic and mesopelagic zones.[30]

Sunfish are most often found in water warmer than 10 °C (50 °F);[30] prolonged periods spent in water at temperatures of 12 °C (54 °F) or lower can lead to disorientation and eventual death.[26] Surface basking behavior, in which a sunfish swims on its side, presenting its largest profile to the sun, may be a method of "thermally recharging" following dives into deeper, colder water in order to feed.[29][31] Sightings of the fish in colder waters outside of its usual habitat, such as those southwest of England, may be evidence of increasing marine temperatures,[32][33] although the proximity of England's southwestern coast to the Gulf Stream means that many of these sightings may also be the result of the fish being carried to Europe by the current.[34]

Sunfish are usually found alone, but occasionally in pairs.[17]

Feeding

The diet of the ocean sunfish was formerly thought to consist primarily of various jellyfish. However, genetic analysis reveals that sunfish are actually generalist predators that consume largely small fish, fish larvae, squid, and crustaceans, with jellyfish and salps making up only around 15% of the diet.[35] Occasionally they will ingest eel grass. This range of food items indicates that the sunfish feeds at many levels, from the surface to deep water, and occasionally down to the seafloor in some areas.[3]

Lifecycle

Ocean sunfish may live up to ten years in captivity, but their lifespan in a natural habitat has not yet been determined.[25] Their growth rate is also undetermined. However, a young specimen at the Monterey Bay Aquarium increased in weight from 26 to 399 kg (57 to 880 lb) and reached a height of nearly 1.8 m (5.9 ft) in 15 months.[26]

The sheer size and thick skin of an adult of the species deters many smaller predators, but younger fish are vulnerable to predation by bluefin tuna and mahi mahi. Adults are consumed by sea lions, orca, and sharks.[17] Sea lions appear to hunt sunfish for sport, tearing the fins off, tossing the body around, and then simply abandoning the still-living but helpless fish to die on the seafloor.[3][26]

The mating practices of the ocean sunfish are poorly understood, but spawning areas have been suggested in the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific, and Indian oceans.[17] Females can produce as many as 300 million eggs at a time, more than any other known vertebrate.[3] Sunfish eggs are released into the water and externally fertilized by sperm.[24]

Newly hatched sunfish larvae are only 2.5 mm (0.1 in) long and weigh a fraction of a gram. They grow to become fry, and those which survive grow many millions of times their original size before reaching adult proportions.[23] Sunfish fry, with large pectoral fins, a tail fin, and body spines uncharacteristic of adult sunfish, resemble miniature pufferfish, their close relatives.[24][36] Young sunfish school for protection, but this behavior is abandoned as they grow.[37] By adulthood, they have the potential to grow more than 60 million times their birth size, arguably the most extreme size growth of any vertebrate animal.[15][38]

Genome

In 2016, researchers from China National Genebank and A*STAR Singapore, including Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner, sequenced the genome of the ocean sunfish and discovered several genes which might explain its fast growth rate and large body size. As member of the order Tetraodontiformes, like fugu, the sunfish has quite a compact genome, at 730 Mb in size. Analysis from this data suggests that sunfish and pufferfishes separated approximately 68 million years ago, which corroborates the results of other recent studies based on smaller datasets.[39]

Human interaction

Despite their size, ocean sunfish are docile, and pose no threat to human divers.[24] Injuries from sunfish are rare, although a slight danger exists from large sunfish leaping out of the water onto boats; in one instance, a sunfish landed on a 4-year-old boy when the fish leaped onto the boy's family's boat.[40] Areas where they are commonly found are popular destinations for sport dives, and sunfish at some locations have reportedly become familiar with divers.[16] The fish is more of a problem to boaters than to swimmers, as it can pose a hazard to watercraft due to its large size and weight. Collisions with sunfish are common in some parts of the world and can cause damage to the hull of a boat,[41] or to the propellers of larger ships, as well as to the fish.[24]

The flesh of the ocean sunfish is considered a delicacy in some regions, the largest markets being Taiwan and Japan. All parts of the sunfish are used in cuisine, from the fins to the internal organs.[20] Some parts of the fish are used in some areas of traditional medicine.[16] Fishery products derived from sunfish are forbidden in the European Union according to Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council as they contain toxins that are harmful to human health.[5]

Sunfish are accidentally but frequently caught in drift gillnet fisheries, making up nearly 30% of the total catch of the swordfish fishery employing drift gillnets in California.[23] The bycatch rate is even higher for the Mediterranean swordfish industry, with 71% to 90% of the total catch being sunfish.[20][37]

The fishery bycatch and destruction of ocean sunfish are unregulated worldwide. In some areas, the fish are "finned" by fishermen who regard them as worthless bait thieves; this process, in which the fins are cut off, results in the eventual death of the fish, because it can no longer propel itself without its dorsal and anal fins.[42] The species is also threatened by floating litter such as plastic bags which resemble jellyfish, a common prey item. Bags can choke and suffocate a fish or fill its stomach to the extent that it starves.[25]

Many areas of sunfish biology remain poorly understood, and various research efforts are underway, including aerial surveys of populations,[43] satellite surveillance using pop-off satellite tags,[20][43] genetic analysis of tissue samples,[20] and collection of amateur sighting data.[44] A decrease in sunfish populations may be caused by more frequent bycatch and the increasing popularity of sunfish in human diet.[17]

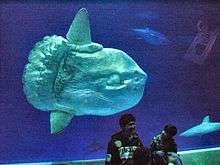

In captivity

Sunfish are not widely held in aquarium exhibits, due to the unique and demanding requirements of their care. Some Asian aquaria display them, particularly in Japan.[26] The Kaiyukan Aquarium in Osaka is one of few aquariums with M. mola on display, where it is reportedly as popular an attraction as the larger whale sharks.[45] The Lisbon Oceanarium in Portugal has sunfish showcased in the main tank,[46] and in Spain, the Valencia Oceanogràfic[47] has specimens of sunfish. The Nordsøen Oceanarium in the northern town of Hirtshals in Denmark is also famous for its sunfish.[48]

While the first ocean sunfish to be held in an aquarium in the United States is claimed to have arrived at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in August 1986,[49] other specimens have previously been held at other locations. Marineland of the Pacific, closed since 1998 and located on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles County, California, held at least one ocean sunfish by 1961,[50] and in 1964 held a 650-pound (290 kg) specimen, claimed as the largest ever captured at that time.[51] However, another 1,000-pound (450 kg) specimen was brought alive to Marineland Studios Aquarium, near St. Augustine, Florida, in 1941.[52]

Because sunfish had not been kept in captivity on a large scale before, the staff at Monterey Bay was forced to innovate and create their own methods for capture, feeding, and parasite control. By 1998, these issues were overcome, and the aquarium was able to hold a specimen for more than a year, later releasing it after its weight increased by more than 14 times.[26] Mola mola has since become a permanent feature of the Open Sea exhibit.[23] Monterey Bay Aquarium's largest sunfish specimen was euthanized on February 14, 2008, after an extended period of poor health.[53]

A major concern to curators is preventive measures taken to keep specimens in captivity from injuring themselves by rubbing against the walls of a tank, since ocean sunfish cannot easily maneuver their bodies.[45] In a smaller tank, hanging a vinyl curtain has been used as a stopgap measure to convert a cuboid tank to a rounded shape and prevent the fish from scraping against the sides. A more effective solution is simply to provide enough room for the sunfish to swim in wide circles.[26] The tank must also be sufficiently deep to accommodate the vertical height of the sunfish, which may reach 3.2 m (10 ft).[11]

Feeding captive sunfish in a tank with other faster-moving, more aggressive fish can also present a challenge. Eventually, the fish can be taught to respond to a floating target to be fed,[54] and to take food from the end of a pole or from human hands.[26]

References

- Liu, J.; Zapfe, G.; Shao, K.-T.; Leis, J.L.; Matsuura, K.; Hardy, G.; Liu, M.; Robertson, R. & Tyler, J. (2015). "Mola mola". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T190422A97667070. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T190422A1951231.en.

- Kyodo (19 November 2015). "IUCN Red List of threatened species includes ocean sunfish". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- Thys, Tierney. "Molidae Descriptions and Life History". OceanSunfish.org. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- Freedman, J. A., & Noakes, D. L. G. (2002) Why are there no really big bony fishes? A point-of-view on maximum body size in teleosts and elasmobranchs. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 12(4): 403-416.

- "Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2007). Species of Mola in FishBase. June 2007 version.

- Parenti, Paolo (September 2003). "Family Molidae Bonaparte 1832: molas or ocean sunfish" (PDF). Annotated Checklist of Fishes (Electronic Journal). 18. ISSN 1545-150X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- "Giant new sunfish species discovered on New Zealand beach (PHOTOS)".

- Bass, L. Anna; Heidi Dewar; Tierney Thys; J. Todd. Streelman; Stephen A. Karl (July 2005). "Evolutionary divergence among lineages of the ocean sunfish family, Molidae (Tetraodontiformes)" (PDF). Marine Biology. 148 (2): 405–414. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0089-z. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- Thys, Tierney. "Molidae information and research (Evolution)". OceanSunfish.org. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- Juliet Rowan (November 24, 2006). "Tropical sunfish visitor as big as a car". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- Watanabe, Y., & Sato, K. (2008). Functional dorsoventral symmetry in relation to lift-based swimming in the ocean sunfish Mola mola. PLoS One, 3(10), e3446.

- Nakatsubo, T., Kawachi, M., Mano, N., & Hirose, H. (2007). Estimation of maturation in wild and captive ocean sunfish Mola mola. Aquaculture Science, 55.

- McClain, Craig R.; Balk, Meghan A.; Benfield, Mark C.; Branch, Trevor A.; Chen, Catherine; Cosgrove, James; Dove, Alistair D.M.; Gaskins, Lindsay C.; Helm, Rebecca R. (2015-01-13). "Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna". PeerJ. 3: e715. doi:10.7717/peerj.715. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4304853. PMID 25649000.

- Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc. (1983), ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "Mola mola" in FishBase. March 2006 version.

- "Mola mola program - Life History". Large Pelagics Research Lab. Archived from the original on 2011-08-19.

- Adam Summers. "No Bones About 'Em". Natural History Magazine. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Bone, Quentin; Moore, Richard (2008). Biology of Fishes. Taylor & Francis US. p. 210. ISBN 978-0203885222.

- Thys, Tierney. "Ongoing Research". OceanSunfish.org. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- "Strange tail of the sunfish". The Natural History Museum. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- Johnson, G. David; Ralf Britz (October 2005). "Leis' Conundrum: Homology of the Clavus of the Ocean Sunfishes. 2. Ontogeny of the Median Fins and Axial Skeleton of Ranzania laevis (Teleostei, Tetraodontiformes, Molidae)". Journal of Morphology. 266 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1002/jmor.10242. PMID 15549687.

We thus conclude that the molid clavus is unequivocally formed by modified elements of the dorsal and anal fin and that the caudal fin is lost in molids.

- "Ocean sunfish". Monterey Bay Aquarium. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- McGrouther, Mark (6 April 2011). "Ocean Sunfish, Mola mola". Australian Museum Online. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- "Mola (Sunfish)". National Geographic. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- Powell, David C. (2001). "21. Pelagic Fishes". A Fascination for Fish: Adventures of an Underwater Pioneer. Berkeley: University of California Press, Monterey Bay Aquarium. pp. 270–275. ISBN 978-0-520-22366-0. OCLC 44425533. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- Ahuir-Baraja, Ana Elena; Padrós, Francesc; Palacios-Abella, Jose Francisco; Raga, Juan Antonio; Montero, Francisco Esteban (15 October 2015). "Accacoelium contortum (Trematoda: Accacoeliidae) a trematode living as a monogenean: morphological and pathological implications". Parasites & Vectors. 8: 540. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-1162-1. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 4608113. PMID 26471059.

- Thys, Tierney (2007). "Help Unravel the Mystery of the Ocean Sunfish". OceanSunfish.org. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- Thys, Tierney (30 November 2003). "Tracking Ocean Sunfish, Mola mola with Pop-Up Satellite Archival Tags in California Waters". OceanSunfish.org. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- "Mola mola program - Preliminary results". Large Pelagics Research Lab. January 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- "The Biogeography of Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola)". San Francisco State University Department of Geography. Fall 2000. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Oliver, Mark & agencies (25 July 2006). "Warm Cornish waters attract new marine life". Guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- "Giant sunfish washed up on Overstrand beach in Norfolk". BBC News Online. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- Ocean Sunfish, Glaucus, British Marine Life Study Society

- Sousa, Lara L.; Xavier, Raquel; Costa, Vânia; Humphries, Nicolas E.; Trueman, Clive; Rosa, Rui; Sims, David W.; Queiroz, Nuno (4 July 2016). "DNA barcoding identifies a cosmopolitan diet in the ocean sunfish". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 28762. Bibcode:2016NatSR...628762S. doi:10.1038/srep28762. PMC 4931451. PMID 27373803.

- Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. "The Ocean Sunfishes or Headfishes". Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Tierney Thys (February 2003). Swim with giant sunfish in the open ocean (Professional conference). Monterey, California, United States: Technology Entertainment Design. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- Kooijman, S. A. L. M., & Lika, K. (2013). Resource allocation to reproduction in animals. Am. Nat. subm, 2(06).

- Pan H, Yu H, Ravi V, et al. (9 September 2016). "The genome of the largest bony fish, ocean sunfish (Mola mola), provides insights into its fast growth rate". GigaScience. 5 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/s13742-016-0144-3. PMC 5016917. PMID 27609345.

- "Boy struck by giant tropical fish". BBC. 2005-08-28. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Lulham, Amanda (23 December 2006). "Giant sunfish alarm crews". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- Thys, Tierney. "Present Fishery/Conservation". Large Pelagics Lab. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- "Current Research". Large Pelagics Research Lab. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- "Have you seen a Mola??". Large Pelagics Research Lab. Archived from the original on 2011-09-01.

- "Main Creature in Kaiyukan". Osaka Kaiyukan Aquarium. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- "Sunfish". Oceanario. Archived from the original on 2015-11-24. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- "Sunfish at Oceanogràfic". Oceanogràfic. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- "The Open Sea". Nordsøen Oceanarium. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- "Aquarium Timeline". Monterey Bay Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- Caldwell, David K.; Brown, David H. (1964). "Notes on killer whales". Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences. 63 (3): 137.

- Los Angeles Times - Jun 15, 1964. p.3

- The Miami News, March 16, 1941, p. 5-C

- "Aquarium Euthanizes Its Largest Ocean Sunfish". KSBW. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- Life in the slow lane. Monterey Bay Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mola mola. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Mola mola |

Research and info

Images and videos

- Mike Johnson Natural History Photography

- Phillip Colla Photography/Oceanlight.com

- Video lecture (16:53): Swim with giant sunfish in the open ocean - Tierney Thys

- Skaphandrus.com Mola mola photos

- Photos of Ocean sunfish on Sealife Collection