Whale shark

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is a slow-moving, filter-feeding carpet shark and the largest known extant fish species. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 18.8 m (62 ft) [8] The whale shark holds many records for size in the animal kingdom, most notably being by far the largest living nonmammalian vertebrate. It is the sole member of the genus Rhincodon and the only extant member of the family Rhincodontidae, which belongs to the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. Before 1984 it was classified as Rhiniodon into Rhinodontidae.

| Whale shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Whale shark in the Andaman Sea around the Similan Islands | |

| |

| The size of various whale shark individuals with a human for scale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Orectolobiformes |

| Family: | Rhincodontidae J. P. Müller and Henle, 1839[3][4] |

| Genus: | Rhincodon A. Smith, 1829[5][4] |

| Species: | R. typus |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhincodon typus | |

| |

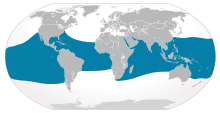

| Range of whale shark | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The whale shark is found in open waters of the tropical oceans and is rarely found in water below 21 °C (70 °F).[2] Modeling suggests a lifespan of about 80 years, and while measurements have proven difficult,[9][10] estimates from field data suggest they may live as long as 130 years.[11] Whale sharks have very large mouths and are filter feeders, which is a feeding mode that occurs in only two other sharks, the megamouth shark and the basking shark. They feed almost exclusively on plankton and small fishes, and pose no threat to humans.

The species was distinguished in April 1828 after the harpooning of a 4.6 m (15 ft) specimen in Table Bay, South Africa. Andrew Smith, a military doctor associated with British troops stationed in Cape Town, described it the following year.[12] The name "whale shark" refers to the fish's size, being as large as some species of whales,[13] and also to its being a filter feeder like baleen whales.

Description

Whale shark mouths can contain over 300 rows of tiny teeth and 20 filter pads which it uses to filter feed.[14] Unlike many other sharks, whale sharks' mouths are located at the front of the head rather than on the underside of the head.[15] A large 12.1 m (39.7 ft) whale shark was reported to have a mouth 1.55 m (5.1 ft) across whilst a smaller 8.75 m (28.7 ft) individual's mouth was reported at 1.7 m (5.6 ft) across.[16][17] Whale sharks have five large pairs of gills. The head is wide and flat with two small eyes at the front corners. Whale sharks are dark grey with a white belly. Their skin is marked with pale grey or white spots and stripes which are unique to each individual. The whale shark has three prominent ridges along its sides, which start above and behind the head and end at the caudal peduncle. Its skin can be up to 15 cm thick and is very hard and rough to the touch. The shark has two dorsal fins set relatively far back on the body, a pair of pectoral fins, a pair of pelvic fins and a single medial anal fin. The tail has a larger upper lobe than the lower lobe (heterocercal). The whale shark's spiracles are just behind its eyes.

Jaws

Jaws Teeth

Teeth- Eye

Top of head

Top of head

The complete and annotated genome of the whale shark was published in 2017.[18]

Size

The whale shark is the largest non-cetacean animal in the world. The average size of adult whale sharks is estimated at 9.8 m (32 ft) and 9 t (20,000 lb).[19] Limited evidence suggests that sexual maturity likely occurs at over 9 m (30 ft) in length.[20][21][22] Specimens near 18 m (59 ft) in length have been reported,[8] however, whale sharks over 12 m (39 ft) are uncommon.[23] The largest total length the species can reach is uncertain due to a lack of information on how measurements were taken in many of the reported individuals.[8] Large whale sharks are difficult to accurately measure both on the land and in the water. When measured on land, the total length can be affected by how the tail is positioned, either being angled as it would be in life or stretched to the maximum possible. Historically, techniques such as comparisons to objects of known size and knotted ropes have been used for in-water measurements and may suffer from inaccuracy.[22] In 2011 laser photogrammetry was proposed to improve measurement accuracy.[24][22]

Reports of large individuals

In 1868, the Irish natural scientist Edward Perceval Wright obtained several small whale shark specimens in the Seychelles. Wright was informed of one whale shark that was actually measured as exceeding 45 ft (14 m). Wright claimed to have observed specimens in excess of 50 ft (15 m) and was told of specimens upwards of 70 ft (21 m).[25]

In a 1925 publication, Hugh M. Smith described a huge animal caught in a bamboo fish trap in Thailand in 1919. The shark was too heavy to pull ashore and no measurements were taken. Smith learned through independent sources that it was at least 10 wa (a Thai unit of length measuring between a persons outstretched arms). Smith noted that one wa could be interpreted as either 2 m (6.6 ft) or the approximate average of 1.7 to 1.8 m (5.6–5.9 ft) based on the local fishermen.[26] Later sources have stated this whale shark as approximately 18 m (59 ft) and the accuracy of the estimate has been questioned.[20][8]

In 1934, a ship named the Maunganui came across a whale shark in the southern Pacific Ocean, rammed it, and the shark became stuck on the prow of the ship, supposedly with 15 ft (4.6 m) on one side and 40 ft (12.2 m) on the other, suggesting a total length of about 55 ft (17 m).[27][28]

A large specimen was caught on 11 November 1949, near Baba Island, in Karachi, Pakistan. It was 11.58 m (38.0 ft) long, weighed about 19.3 t (43,000 lb), and had a girth of 7 m (23 ft).[19]. In 1983 a whale shark was caught in a net off the coast of Mumbai and detailed measurements were taken from all over the body; it was found to have a total length of 12.18 m (40.0 ft) with an approximate estimated weight of 11,018 kg (24,291 lb).[29][20] This was considered the largest accurately measured specimen by J. G. Coleman in 1997.[20]

A shark caught in 1994 off Tainan County, southern Taiwan, reportedly weighed 35.8 t (79,000 lb).[30] Using length to weight equations calculated from whale sharks, Hua Hsun Hsu and colleagues estimated two individuals reported as weighing 34 t (75,000 lb) and 42 t (93,000 lb) at 16 m (52 ft) and 17.3 m (57 ft) in length respectively.[9]

Scott A. Eckert & Brent S. Stewart reported on satellite tracking of whale sharks from between 1994 and 1996. Out of the 15 individuals tracked, two females were reported as measuring 15 m (49 ft) and 18 m (59 ft) respectively.[31] A whale shark was reported as being stranded in 1995, along the Ratnagiri coast, measuring 20.75 m (68.1 ft) long.[32][17] A female individual with a standard length of 15 m (49 ft) (and an estimated total length at 18.8 m (62 ft)) was reported from the Arabian Sea in 2001.[33] In a 2015 study looking into the size of marine megafauna, McClain and colleagues considered this female as being the most reliable and accurately measured.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The whale shark inhabits all tropical and warm-temperate seas. The fish is primarily pelagic, living in the open sea but not in the greater depths of the ocean, although it is known to occasionally dive to depths of as much as 1,800 metres (5,900 ft).[34] Seasonal feeding aggregations occur at several coastal sites such as the southern and eastern parts of South Africa; Saint Helena Island in the South Atlantic Ocean; Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, Gladden Spit in Belize; Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia; Kerala,[35] Lakshadweep, Gulf of Kutch and Saurashtra coast of Gujarat in India;[36] Útila in Honduras; Southern Leyte; Donsol, Pasacao and Batangas in the Philippines; off Isla Mujeres and Isla Holbox in Yucatan and Bahía de los Ángeles in Baja California, México; Maamigili island, Maldives; Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia; Cenderawasih Bay National Park in Nabire, Papua, Indonesia; Flores Island, Indonesia; Nosy Be in Madagascar; off Tofo Beach near Inhambane in Mozambique; the Tanzanian islands of Mafia, Pemba, Zanzibar; Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, the Ad Dimaniyat Islands in the Gulf of Oman and Al Hallaniyat islands in the Arabian Sea; and, very rarely, Eilat, Israel and Aqaba, Jordan. Although typically seen offshore, it has been found closer to land, entering lagoons or coral atolls, and near the mouths of estuaries and rivers. Its range is generally restricted to about 30° latitude or lower. It is capable of diving to depths of at least 1,286 m (4,219 ft),[37] and is migratory.[10] On 7 February 2012, a large whale shark was found floating 150 kilometres (93 mi) off the coast of Karachi, Pakistan. The length of the specimen was said to be between 11 and 12 m (36 and 39 ft), with a weight of around 15,000 kg (33,000 lb).[38]

In 2011, more than 400 whale sharks gathered off the Yucatan Coast. It was one of the largest gatherings of whale sharks recorded.[39] Aggregations in that area are among the most reliable seasonal gatherings known for whale sharks, with large numbers occurring in most years between May and September. Associated ecotourism has grown rapidly to unsustainable levels.[40]

Reproduction

Pupping of whale sharks has not been observed, but mating has been witnessed twice in St Helena.[41] Mating in this species was filmed for the first time in whale sharks off Ningaloo Reef via airplane in Australia in 2019, when a larger male unsuccessfully attempted to mate with a smaller, immature female.[42]

The capture of a female in July 1996 that was pregnant with 300 pups indicated that whale sharks are ovoviviparous.[10][43][44] The eggs remain in the body and the females give birth to live young which are 40 to 60 cm (16 to 24 in) long. Evidence indicates the pups are not all born at once, but rather the female retains sperm from one mating and produces a steady stream of pups over a prolonged period.[45] Studies disagreed over whether vertebrae growth bands were formed annually or biannually, which is important in determining the age, growth, and longevity of whale sharks.[46][9][11] A 2020 study compared the ratio of Carbon-14 isotopes found in growth bands of whale shark vertebrae to nuclear testing events in the 1950-60s, they found that growth bands were laid down annually and found an age of 50 years for a 10 m (33 ft) female.[47] This means whale sharks exhibit late sexual maturity,[47] estimates for ages at maturity in males are ~25 years.[11] Various studies looking at vertebrae growth bands and measuring whale sharks in the wild have estimated their lifespans from ~80 years and up to ~130 years.[9][10][11]

On 7 March 2009, marine scientists in the Philippines discovered what is believed to be the smallest living specimen of the whale shark. The young shark, measuring only 38 cm (15 in), was found with its tail tied to a stake at a beach in Pilar, Sorsogon, Philippines, and was released into the wild. Based on this discovery, some scientists no longer believe this area is just a feeding ground; this site may be a birthing ground, as well. Both young whale sharks and pregnant females have been seen in the waters of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, where numerous whale sharks can be spotted during the summer.[48][49]

In a report from Rappler last August 2019, whale sharks were sighted during WWF Philippines’ photo identification activities in the first half of the year. There were a total 168 sightings – 64 of them “re-sightings” or reappearances of previously recorded whale sharks. WWF noted that “very young whale shark juveniles" were identified among the 168 individuals spotted in the first half of 2019. Their presence suggests that the Ticao Pass may be a pupping ground for whale sharks, further increasing the ecological significance of the area. Per Dr Andy Cornish, "Protecting more marine areas near Donsol could play a key role in enhancing protection for these endangered ocean nomads for generations to come." WWF Philippines is working closely with the local government since 1998 for the conservation of Ticao Pass as these coastal areas face a rampant problem of marine trash with single-use sachets, plastic bottles and other hazardous wastes.[50] The Philippines’ law on solid waste is poorly enforced and the country doesn’t even regulate packaging manufacturing. As the country does not have a clear waste segregation plan, sachets and other waste are thrown in estuaries or dumped on the street, and end up clogging drains and waterways, much of the trash ends up in the sea.[51]

Diet

The whale shark is a filter feeder – one of only three known filter-feeding shark species (along with the basking shark and the megamouth shark). It feeds on plankton including copepods, krill, fish eggs, Christmas Island red crab larvae [52] and small nektonic life, such as small squid or fish. It also feeds on clouds of eggs during mass spawning of fish and corals.[53] The many rows of vestigial teeth play no role in feeding. Feeding occurs either by ram filtration, in which the animal opens its mouth and swims forward, pushing water and food into the mouth, or by active suction feeding, in which the animal opens and closes its mouth, sucking in volumes of water that are then expelled through the gills. In both cases, the filter pads serve to separate food from water. These unique, black sieve-like structures are presumed to be modified gill rakers. Food separation in whale sharks is by cross-flow filtration, in which the water travels nearly parallel to the filter pad surface, not perpendicularly through it, before passing to the outside, while denser food particles continue to the back of the throat.[54] This is an extremely efficient filtration method that minimizes fouling of the filter pad surface. Whale sharks have been observed "coughing", presumably to clear a build-up of particles from the filter pads. Whale sharks migrate to feed and possibly to breed.[10][55][56]

The whale shark is an active feeder, targeting concentrations of plankton or fish. It is able to ram filter feed or can gulp in a stationary position. This is in contrast to the passive feeding basking shark, which does not pump water. Instead, it swims to force water across its gills.[10][55]

A juvenile whale shark is estimated to eat 21 kg (46 pounds) of plankton per day.[57]

The BBC program Planet Earth filmed a whale shark feeding on a school of small fish. The same documentary showed footage of a whale shark timing its arrival to coincide with the mass spawning of fish shoals and feeding on the resultant clouds of eggs and sperm.[53]

Whale sharks are known to prey on a range of planktonic and small nektonic organisms that are spatiotemporally patchy. These include krill, crab larvae, jellyfish, sardines, anchovies, mackerels, small tunas, and squid. In ram filter feeding, the fish swims forward at constant speed with its mouth fully open, straining prey particles from the water by forward propulsion. This is also called ‘passive feeding’, which usually occurs when prey is present at low density.[58]

Relationship with humans

Behavior toward divers

Despite its size, the whale shark does not pose any danger to humans. Whale sharks are docile fish and sometimes allow swimmers to catch a ride,[59][60][61] although this practice is discouraged by shark scientists and conservationists because of the disturbance to the sharks.[62] Younger whale sharks are gentle and can play with divers. Underwater photographers such as Fiona Ayerst have photographed them swimming close to humans without any danger.[63]

The shark is seen by divers in many places, including the Bay Islands in Honduras, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, the Maldives close to Maamigili (South Ari Atoll), the Red Sea, Western Australia (Ningaloo Reef, Christmas Island), Taiwan, Panama (Coiba Island), Belize, Tofo Beach in Mozambique, Sodwana Bay (Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park) in South Africa,[63] the Galapagos Islands, Saint Helena, Isla Mujeres (Caribbean Sea), La Paz, Baja California Sur and Bahía de los Ángeles in Mexico, the Seychelles, West Malaysia, islands off eastern peninsular Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Oman, Fujairah, Puerto Rico, and other parts of the Caribbean.[59] Juveniles can be found near the shore in the Gulf of Tadjoura, near Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa.[64]

Conservation status

There is currently no robust estimate of the global whale shark population. The species is considered endangered by the IUCN due to the impacts of fisheries, by-catch losses, and vessel strikes, combined with its long lifespan and late maturation.[2] In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the whale shark as "Migrant" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[65]

It is listed, along with six other species of sharks, under the CMS Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks.[66] In 1998, the Philippines banned all fishing, selling, importing, and exporting of whale sharks for commercial purposes,[67] followed by India in May 2001,[68] and Taiwan in May 2007.[69]

In 2010, the Gulf of Mexico oil spill resulted in 4,900,000 barrels (780,000 m3) of oil flowing into an area south of the Mississippi River Delta, where one-third of all whale shark sightings in the northern part of the gulf have occurred in recent years. Sightings confirmed that the whale sharks were unable to avoid the oil slick, which was situated on the surface of the sea where the whale sharks feed for several hours at a time. No dead whale sharks were found.[70]

This species was also added to Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 2003 to regulate the international trade of live specimens and its parts.[71]

Hundreds of whale sharks are illegally killed every year in China for their fins, skins, and oil.[72]

In captivity

The whale shark is popular in the few public aquariums that keep it, but its large size means that a very large tank is required and it has specialized feeding requirements.[73] Their large size and iconic status have also fueled an opposition to keeping the species in captivity, especially after the early death of some whale sharks in captivity and certain Chinese aquariums keeping the species in relatively small tanks.[74][75]

The first attempt at keeping whale sharks in captivity was in 1934 when an individual was kept for about four months in a netted-off natural bay in Izu, Japan.[76] The first attempt of keeping whale sharks in an aquarium was initiated in 1980 by the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium (then known as Ocean Expo Park) in Japan.[73] Since 1980, several have been kept at Okinawa, mostly obtained from incidental catches in coastal nets set by fishers (none after 2009), but two were strandings. Several of these were already weak from the capture/stranding and some were released,[73] but initial captive survival rates were low.[75] After the initial difficulties in maintaining the species had been resolved, some have survived long-term in captivity.[73] The record for a whale shark in captivity is an individual that, as of 2017, has lived for more than 18 years in the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium.[73] Following Okinawa, Osaka Aquarium started keeping whale sharks and most of the basic research on the keeping of the species was made at these two institutions.[77] Since the mid-1990s, several other aquariums have kept the species in Japan (Kagoshima City Aquarium, Kinosaki Marine World, Notojima Aquarium, Oita Ecological Aquarium, and Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea Paradise), South Korea (Aquaplanet Jeju), China (Chimelong Ocean Kingdom, Dalian Aquarium, Guangzhou Aquarium in Guangzhou Zoo, Qingdao Polar Ocean World and Yantai Aquarium), Taiwan (National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium), India (Thiruvananthapuram Aquarium) and Dubai (Atlantis, The Palm), with some maintaining whale sharks for years and others only for a very short period.[76] The whale shark kept at Dubai's Atlantis, The Palm was rescued from shallow waters in 2008 with extensive abrasions to the fins and after rehabilitation it was released in 2010, having lived 19 months in captivity.[78][79] Marine Life Park in Singapore had planned on keeping whale sharks, but scrapped this idea in 2009.[80][81]

Outside Asia, the first and so far only place to keep whale sharks is Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta, United States.[76] This is unusual because of the comparatively long transport time and complex logistics required to bring the sharks to the aquarium, ranging between 28 and 36 hours.[77] Georgia keeps four whale sharks: two females, Alice and Trixie, that arrived in 2006,[82] and two males, Taroko and Yushan, that arrived in 2007.[83] Two earlier males at Georgia Aquarium, Ralph and Norton, both died in 2007.[75] Georgia's whale sharks were all imported from Taiwan and were taken from the commercial fishing quota for the species, usually used locally for food.[77][84] Taiwan closed this fishery entirely in 2008.[84]

Human culture

In Madagascar, whale sharks are called marokintana in Malagasy, meaning "many stars", after the appearance of the markings on the shark's back.[85]

In the Philippines, it is called butanding and balilan.[86] The whale shark is featured on the reverse of the Philippine 100-peso bill. By law snorkelers must maintain a distance of four feet from the sharks and there is a fine and possible prison sentence for anyone who touches the animals.[87]

Whale sharks are also known as jinbei-zame in Japan (because the markings resemble jinbei); gurano bintang in Indonesia; and ca ong (literally "sir fish") in Vietnam.[88]

The whale shark is also featured on the latest 2015–2017 edition of the Maldivian 1000 rufiyaa banknote, along with the green turtle.

See also

- List of sharks

- List of threatened sharks

References

- "Rhincodon typus in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Pierce, S. J. & Norman, B. (2016). "Rhincodon typus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T19488A2365291. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T19488A2365291.en.

- Müller, J.; Henle, J. (1841). Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen. Berlin: Veit und Comp. p. 77.

- Melville, R. V. (1981). "Opinion 1278. The Generic Name Rhincodon A. Smith, 1829 (Pisces): Conserved". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 41 (4): 215–217.

- Smith, Andrew (1829). "Contributions to the Natural History of South Africa, &c". The Zoological Journal. 4: 443–444.

- Smith, Andrew (5 November 1828). "Descriptions of New or imperfectly known Objects of the Animal Kingdom, found in the South of Africa". The South African Commercial Advertiser. 3 (145) – via Center for Research Libraries Document Delivery System. Reprinted in Penrith (1972).

- Penrith, M. J. (1972). "Earliest Description and Name for the Whale Shark". Copeia. 1972 (2): 362. doi:10.2307/1442501. JSTOR 1442501.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClain CR, Balk MA, Benfield MC, Branch TA, Chen C, Cosgrove J, Dove ADM, Gaskins LC, Helm RR, Hochberg FG, Lee FB, Marshall A, McMurray SE, Schanche C, Stone SN, Thaler AD. 2015. Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3:e715 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.715

- Hsu, Hua Hsun; Joung, Shoou Jeng; Hueter, Robert E.; Liu, Kwang Ming (2014). "Age and growth of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) in the north-western Pacific". Marine and Freshwater Research. 65 (12): 1145. doi:10.1071/MF13330. ISSN 1323-1650.

- Colman, J. G. Froese, Ranier; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Rhincodon typus". FishBase. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- Perry, Cameron T.; Figueiredo, Joana; Vaudo, Jeremy J.; Hancock, James; Rees, Richard; Shivji, Mahmood (2018). "Comparing length-measurement methods and estimating growth parameters of free-swimming whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) near the South Ari Atoll, Maldives". Marine and Freshwater Research. 69 (10): 1487. doi:10.1071/MF17393. ISSN 1323-1650.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Rhincodon or Rhiniodon? A Whale Shark by any Other Name". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.

- Brunnschweiler, J. M.; Baensch, H.; Pierce, S. J.; Sims, D. W. (3 February 2009). "Deep-diving behaviour of a whale shark Rhincodon typus during long-distance movement in the western Indian Ocean". Journal of Fish Biology. 74 (3): 706–14. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02155.x. PMID 20735591.

- Compagno, L. J. V. "Species Fact Sheet, Rhincodon typus". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- "Whale Sharks, Rhincodon typus". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Kaikini, A. S.; Ramamohana Rao, V.; Dhulkhed, M. H. (1959). "A note on the whale shark Rhincodon typus Smith, stranded off Mangalore". Central Marine Fisheries Research Unit, Mangalore.

- Venkatesan, V; Ramamurthy, N; Boominathan, N; Gandhi, A (2008). "Stranding of a whale shark, Rhincodon typus (smith) at Pamban, Gulf of Mannar" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Information Service. 198: 19–22.

- Read, Timothy D.; Petit, Robert A.; Joseph, Sandeep J.; Alam, Md. Tauqeer; Weil, M. Ryan; Ahmad, Maida; Bhimani, Ravila; Vuong, Jocelyn S.; Haase, Chad P. (December 2017). "Draft sequencing and assembly of the genome of the world's largest fish, the whale shark: Rhincodon typus Smith 1828". BMC Genomics. 18 (1): 532. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3926-9. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 5513125. PMID 28709399.

- Wood, Gerald L. (1976). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-0-900424-60-1.

- Colman, J. G. (1997). "A review of the biology and ecology of the whale shark". Journal of Fish Biology. 51 (6): 1219–1234. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01138.x. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 29991171.

- Stevens, J. D. (1 March 2007). "Whale shark (Rhincodon typus) biology and ecology: A review of the primary literature". Fisheries Research. Whale Sharks: Science, Conservation and Management. 84 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2006.11.008. ISSN 0165-7836.

- Rowat, D.; Brooks, K. S. (2012). "A review of the biology, fisheries and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus". Journal of Fish Biology. 80 (5): 1019–1056. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03252.x. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 22497372.

- Compagno, Leonard J. V. (1984). Sharks of the world : an annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date Vol 2. Rome: United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 9251013845. OCLC 12214754.

- Rohner, C. A.; Richardson, A. J.; Marshall, A. D.; Weeks, S. J.; Pierce, S. J. (2011). "How large is the world's largest fish? Measuring whale sharks Rhincodon typus with laser photogrammetry". Journal of Fish Biology. 78 (1): 378–385. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02861.x. PMID 21235570.

- Wright, E. Perceval (Edward Perceval), 1834-1910. (2011). Six months at the Seychelles : letter to A. Searle Hart, LL. D., S.F.T.C.D. British Library, Historical Print Editions. ISBN 9781241491611. OCLC 835888086.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smith, H. M. (13 November 1925). "A Whale Shark (Rhineodon) in the Gulf of Siam". Science. 62 (1611): 438. Bibcode:1925Sci....62..438S. doi:10.1126/science.62.1611.438. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17732228.

- Gudger, E. W. (1938). "Whale Sharks Rammed by Ocean Vessels: How These Sluggish Leviathans Aid in Their Own Destruction". New England Naturalist. New England Museum of Natural History: Boston Society of Natural History. 1–15. OCLC 1759776.

- Maniguet, Xavier (1992). The Jaws of Death: Shark as Predator, Man as Prey. HarperCollins Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-0-00-219960-5.

- Karbhari, J. P.; Josekutty, C. J. (1986). "On the largest whale shark Rhincodon typus Smith landed alive at Cuffe Parade, Bombay". Marine Fisheries Information Service, Technical and Extension Series. 66: 31–35.

- Mollet, H. F. (2008). "Summary of Large Whale Shark Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828". Archived from the original on 12 March 2012.. Home Page of Henry F. Mollet, Research Affiliate, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories.

- Eckert, Scott A.; Stewart, Brent S. (1 February 2001). "Telemetry and Satellite Tracking of Whale Sharks, Rhincodon Typus, in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico, and the North Pacific Ocean". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 60 (1): 299–308. doi:10.1023/A:1007674716437. ISSN 1573-5133.

- Katkar, B.N. (1996). "Turtles and whale shark landed along ratnagiri coast, maharashtra". Marine Fisheries Information Service. 141: 20.

- Borrell, Asunción; Aguilar, Alex; Gazo, Manel; Kumarran, R. P.; Cardona, Luis (2011). "Stable isotope profiles in whale shark (Rhincodon typus) suggest segregation and dissimilarities in the diet depending on sex and size". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 92 (4): 559–567. doi:10.1007/s10641-011-9879-y. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Howard, Brian C. (28 June 2016). "Whale Sharks Move in Mysterious Ways: Watch Them Online". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Drive to conserve whale shark". The Hindu. 30 August 2017 – via www.thehindu.com.

- Kaushik, Himanshu (30 August 2014). "Whale sharks found off Gujarat coast no expats, they are Indian". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Brunnschweiler, Juerg M.; Baensch, H.; Pierce, S. J.; Sims, D. W. (2009). "Deep-diving behaviour of a whale shark Rhincodon typus during long-distance movement in the western Indian Ocean". Journal of Fish Biology. 74 (3): 706–714. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02155.x. PMID 20735591.

- Hasan, Saad (10 February 2012). "Experts to cut up 40.1-foot long whale shark today". The Express Tribune.

- de la Parra Venegas, Rafael; Hueter, Robert; Cano, Jaime González; Tyminski, John; Remolina, José Gregorio; Maslanka, Mike; Ormos, Andrea; Weigt, Lee; Carlson, Bruce; Dove, Alistair (29 April 2011). "An Unprecedented Aggregation of Whale Sharks, Rhincodon typus, in Mexican Coastal Waters of the Caribbean Sea". PLoS ONE. 4. 6 (4): e18994. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618994D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018994. PMC 3084747. PMID 21559508.

- Dove, Alistair (27 January 2015), Yucatan Whale Sharks Swimming in Troubled Waters, archived from the original on 7 November 2017

- Clingham, Elizabeth; Brown, Judith; Henry, Leeann; Beard, Annalea; Dove, Alistair D (2016). Evidence that St. Helena island is an important multi-use habitat for whale sharks, Rhincodon typus , with the first description of putative mating in this species. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.1885v1. OCLC 8162956757.

- "Attempted Whale Shark Mating Caught on Camera for the First Time in History". livescience.com.

- Joung, Shoou-Jeng; et al. (July 1996). "The whale shark, Rhincodon typus, is a livebearer: 300 embryos found in one 'megamamma' supreme". Environ. Biol. Fish. 46 (3): 219–223. doi:10.1007/BF00004997.

- Clark, Eugenie. "Frequently Asked Questions". Sharklady. Archived from the original on 5 March 2001. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- Schmidt, Jennifer V.; Chen, Chien-Chi; Sheikh, Saad I.; Meekan, Mark G.; Norman, Bradley M.; Joung, Shoou-Jeng (4 August 2010). "Paternity analysis in a litter of whale shark embryos". Endangered Species Research. 12 (2): 117–124. doi:10.3354/esr00300.

- Wintner, Sabine P. (2000). "Preliminary Study of Vertebral Growth Rings in the Whale Shark, Rhincodon typus, from the East Coast of South Africa". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 59 (4): 441–451. doi:10.1023/A:1026564707027.

- Ong, Joyce J. L.; Meekan, Mark G.; Hsu, Hua Hsun; Fanning, L. Paul; Campana, Steven E. (6 April 2020). "Annual Bands in Vertebrae Validated by Bomb Radiocarbon Assays Provide Estimates of Age and Growth of Whale Sharks". Frontiers in Marine Science. 7. doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00188.

- "Tiny whale shark rescued – World news – World environment". Associated Press via NBC News. 2009.

- "St Helena whale sharks cause stir in Atlanta". South Atlantic Media Services. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "'Largest number in years': Over 100 new whale sharks spotted in Donsol". Rappler.com. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Lema, Karen (3 September 2019). "Slave to sachets: How poverty worsens the plastics crisis in the Philippines". Reuters. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Morelle, Rebecca (17 November 2008). "Shark-cam captures ocean motion". BBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- Jurassic Shark (2000) documentary by Jacinth O'Donnell; broadcast on Discovery Channel, 5 August 2006

- Motta, Philip J.; et al. (2010). "Feeding anatomy, filter-feeding rate, and diet of whale sharks Rhincodon typus during surface ram filter feeding off the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico" (PDF). Zoology. 113 (4): 199–212. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2009.12.001. PMID 20817493.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Elasmo Research". ReefQuest. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- "Whale shark". Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 11 May 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- Schmidt, Jennifer V. (4 December 2010). "Whale Sharks are BIG eaters!". The Shark Research Institute. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Rhincodon typus (whale shark)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Compagno, Leonard J. V. (26 April 2002). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date: Bullhead, Mackerel and Carpet Sharks. 2. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). ISBN 978-92-5-104543-5.

- "Favorite Wins of 2013". Break.com. p. 1:24. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Robbins J. (18 July 2017). Watch Iranian fisherman 'surf' on top of a whale shark across the Persian Gulf. International Business Times. Retrieved on 29 September 2017

- Whitehead, Darren Andrew (2014) Establishing a quantifiable model of whale shark avoidance behaviours to anthropogenic impacts in tourism encounters to inform management actions, University of Hertfordshire.

- Pictures of the Day: Tuesday, Aug. 04, 2009. Time magazine, "A 40-foot whale shark and a brave snorkeler swim off the South African coast."

- Hawes, Craig (2 April 2013) Snorkelling with whale sharks in Djibouti. gulfnews.com

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 11. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

- "Memorandum of understanding on the conservation of migratory sharks" (PDF). Convention on migratory species. p. 10. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Whale Sharks Receive Protection in the Philippines. hayop.0catch.com. 27 March 1998

- National Regulations on Whale Shark fishing. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.

- COA bans fishing for whale sharks. Taipei Times, 27 May 2007, p. 4.

- Handwerk, Brian (24 September 2010) Whale Sharks Killed, Displaced by Gulf Oil? National Geographic News.

- Whale shark. cites.org

- "Hundreds of sharks killed in China". 5 February 2014.

- Matsumoto; Toda; Matsumoto; Ueda; Nakazato; Sato; Uchida (2017). "Notes on Husbandry of Whale Sharks, Rhincodon typus, in Aquaria". In Smith, Mark; Warmolts; Thoney; Hueter; Murray; Ezcurra (eds.). The Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 15–22. ISBN 9780867271676. OCLC 1001957014.

- "Whale Shark's Death Sparks Debate". wsbtv. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010.

- Moore, M. (25 October 2010). "Conservationists round on Chinese whale shark aquarium". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Mollet, H. (September 2012). "Whale Shark Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828 in Captivity". Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Schreiber, C; Coco, C (2017). "Husbandry of Whale Sharks". In Smith, Mark; Warmolts; Thoney; Hueter; Murray; Ezcurra (eds.). The Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 87–98. ISBN 9780867271676. OCLC 1001957014.

- "Dubai hotel releases whale shark back into the wild". Associated Press. 20 March 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015.

- Bennett; Kaiser; Selvan; Hueter; Tyminski; Lötter (2017). "Rescue, Rehabilitation and Release of a Whale Shark, Rhincodon typus, in the Arabian Gulf". In Smith, Mark; Warmolts; Thoney; Hueter; Murray; Ezcurra (eds.). The Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 229–235. ISBN 9780867271676. OCLC 1001957014.

- Chua, G. (16 May 2009). "No whale sharks at Sentosa IR". Wild Singapore News. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "Resorts World considering alternatives to whale shark exhibit". AsianOne Travel. 16 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013.

- Moore, M. (4 June 2006). "Georgia Aquarium Whale Sharks Receive Special UPS Delivery; Two Resident Male Whale Sharks are Joined by Two Females". BusinessWire. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "Aquarium gains two new whale sharks". CNN. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 June 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- Sundquist, T. (18 September 2013). "Transporting the World's Largest Fish: A Whale [Shark] of a Task". Promega Connections. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Briggs, Helen (17 May 2018). "Madagascar emerges as whale shark hotspot". BBC News. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Ocean Ambassadors – Sharks. Oneocean.org. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Cannon, Marisa (21 July 2015). "Swimming with whale sharks in the Philippines". cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- "Whale Shark". Discovery.com. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

Further reading

- Colman, J.G. (December 1997). "A review of the biology and ecology of the whale shark". J. Fish Biol. 51 (6): 1219–34. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01138.x. PMID 29991171.

- FAO web page on Whale shark

- "Whale Sharks, Whale Shark Pictures, Whale Shark Facts". Animals, Animal Pictures, Wild Animal Facts. 10 September 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whale sharks. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Whale sharks |

- Whale Shark Photograph-identification Library

- Whale Shark And Oceanic Research Center

- Maldives Whale Shark Research Program

- Whale Sharks: Gentle Giants of the Seas

- Foundation for the Protection of Marine Megafauna

- Whale shark, Rhincodon typus at marinebio.org

- Whale Shark Fact Sheet, Fisheries Western Australia

- Albino whale shark photographed in Galapagos

- Photographs National Geographic

- A whale shark recorded defecating

- Photos of Whale shark on Sealife Collection