Nicotiana tabacum

Nicotiana tabacum, or cultivated tobacco, is an annually-grown herbaceous plant. It is found in cultivation, where it is the most commonly grown of all plants in the genus Nicotiana, and its leaves are commercially grown in many countries to be processed into tobacco. It grows to heights between 1 and 2 meters. Research is ongoing into its ancestry among wild Nicotiana species, but it is believed to be a hybrid of Nicotiana sylvestris, Nicotiana tomentosiformis, and possibly Nicotiana otophora.[1]

| Nicotiana tabacum | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Nicotiana |

| Species: | N. tabacum |

| Binomial name | |

| Nicotiana tabacum | |

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Chemistry |

|

| Biology |

|

| Personal and social impact |

|

| Production |

|

History

The plant is native to the Caribbean, where the Arawak/Taino people were the first to use it and cultivate it. In 1560, Jean Nicot de Villemain, then French ambassador to Portugal, brought tobacco seeds and leaves as a "wonder drug" to the French court. In 1586 the botanist Jaques Dalechamps gave the plant the name of Herba nicotiana, which was also adopted by Linné. It was considered a decorative plant at first, then a panacea, before it became a common snuff and tobacco plant. Tobacco arrived in Africa at the beginning of the 17th century. The leaf extract was a popular pest control method up to the beginning of the 20th century. In 1851, the Belgian chemist Jean Stas documented the use of tobacco extract as a murder poison. The Belgian count Hippolyte Visart de Bocarmé had poisoned his brother-in-law with tobacco leaf extract in order to acquire some urgently needed money. This was the first exact proof of alkaloids in forensic medicine.[2]

Habitat and ecology

N. tabacum is a native of tropical and subtropical America but it is now commercially cultivated worldwide. Other varieties are cultivated as ornamental plants or grown as a weed.

N. tabacum is sensitive to temperature, air, ground humidity and the type of land. Temperatures of 20–30 °C (68–86 °F) are best for adequate growth; an atmospheric humidity of 80 to 85% and soil without a high level of nitrogen are also optimal.

Parasites

The potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella) is an oligophagous insect that prefers to feed on plants of the family Solanaceae such as tobacco plants. Female P. operculella use the leaves to lay their eggs and the hatched larvae will eat away at the mesophyll of the leaf.[3]

Botanical description

Nicotiana tabacum Linné is a robust annual branched herb up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) tall, with large green leaves and long, trumpet-shaped, white-pinkish flowers. All parts of the plant are sticky, being covered with short viscid-glandular hairs which exude a yellow secretion containing nicotine.

Leaves

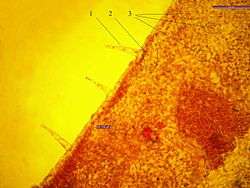

1. Trichomes

2. Epidermal cells

3. Stomata

Varied in size, the lower leaves are the largest at up to 60 cm (24 in) long, short-stalked or unstalked, oblonged-elliptic, shortly acuminate at the apex, decurrent at the base, the following leaves decrease in size, the upper one sessile and smallest, oblong- lanceolate or elliptic.

Flowers

In terminal, many flowered inflorescences, the tube 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) long, 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter, expanded in the lower third (calyx) and upper third (throat), lobes broadly triangular, white-pinkish with pale violet or carmine colored tips tube yellowish white; calyx with five narrowly triangular lobes which are 1.5–2 cm (0.59–0.79 in) long. A capsular ovoid or ellipsoid, surrounded by the persistent calyx and with a short apical beak, about 2 cm (0.79 in) long. Seeds are very numerous, very small, ovoid or kidney shaped, brown.

Part used

Almost every part of the plant except the seed contains nicotine, but the concentration is related to different factors such as species, type of land, culture and weather conditions. The concentration of nicotine increases with the age of the plant. Tobacco leaves contain 2 to 8% nicotine combined as malate or citrate. The distribution of the nicotine in the mature plant is widely variable: 64% of the total nicotine exists in the leaves, 18% in the stem, 13% in the root, and 5% in the flowers.

Phytochemicals

Natural tobacco polysaccharides, including cellulose, have been shown to be the primary precursors of acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke.[4] The main polyphenols contained in the tobacco leaf are rutin and chlorogenic acid. Amino acids contained include glutamic acids, asparagine, glutamine, and γ-Aminobutyric acid [5]

Pyridine alkaloids are present in tobacco as free bases and salts. Nicotine accounts for 90-95% of the plant's pyridines with Nornicotine and anatabine accounting for roughly 2.5% each. Pyridyl functional groups present in minute amounts include anabasine, myosmine, cotinine and 2, 3′-bipyridyl.[6]

The tobacco plant readily absorbs heavy metals from the surrounding soil and accumulates them in its leaves. These are readily absorbed into the user's body following smoke inhalation.[7]

Tobacco also contains the following phytochemicals: glucosides (tabacinine, tabacine), 2,3,6-trimethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone, 2-methylquinone, 2-napthylamine, propionic acid, anthalin, anethole, acrolein, cembrene, choline, nicotelline, nicotianine, and pyrene.[8]

Ethnomedicinal uses

The regions that have histories of use of the plant include:

- Brazil: The leaf juice is taken orally to induce vomiting and narcosis.

- Colombia: Fresh leaf is used as poultice over boils and infected wounds; the leaves are crushed with oil from palms and used as hair treatment to prevent baldness.

- Cuba: Extract of the leaf is taken orally to treat dysmenorrhea.

- East Africa: Dried leaves of Nicotiana tabacum and Securinega virosa are mixed into a paste and used externally to destroy worms in sores.

- Ecuador: Leaf juice is used for indisposition, chills and snake bites and to treat pulmonary ailments.

- Fiji: Fresh root is taken orally for asthma and indigestion; fresh root is applied ophthalmically as drops for bloodshot eyes and other problems; seed is taken orally for rheumatism and to treat hoarsness.

- Guatemala: Leaves are applied externally by adults for myiasis, headache and wounds; hot water extract of the dried leaf is applied externally for ring worms, fungal diseases of the skin, wounds, ulcers, bruises, sores, mouth lesions, stomatitis and mucosa; leaf is orally taken for kidney diseases.

- Haiti: Decoction of dried leaf is taken orally for bronchitis and pneumonia.

- Iran: Infusion of the dried leaf is applied externally as an insect repellent; ointments made from crushed leaves are used for baldness, dermatitis and infectious ulceration and as a pediculicide.

- Mexico (south-eastern): Among the ancient Maya, Nicotiana was considered a sacred plant, closely associated with deities of earth and sky, and used for both visionary and therapeutic ends. The contemporary Tzeltal and Tzotzil Maya of Highland Chiapas (Mexico) are bearers of this ethnobotanical inheritance, preserving a rich and varied tradition of Nicotiana use and folklore. The entire tobacco plant is viewed as a primordial medicine and a powerful botanical "helper" or "protector". Depending on the condition to be treated, whole Nicotiana leaves are used alone or in combination with other herbs in the preparation of various medicinal plasters and teas. In its most common form, fresh or ‘‘green’’ leaves are ground with slaked lime to produce an intoxicating oral snuff that serves as both a protective and therapeutic agent.[9]

- United States: Extract of N. tabacum is taken orally to treat tiredness, ward off diseases, and quiet fear.

- Tanzania: Leaves of Nicotiana tabacum are placed in the vagina to stimulate labour.

- Hong Kong: Fresh Leaves are mashed and combined with vegetable oil to create a potion that is applied to injuries for it to heal faster. This practice is also apparent in other places in China.

Other uses

A protein of the White–Brown complex subfamily[10] can be extracted from the leaves. It is an odourless, tasteless white powder and can be added to cereal grains, vegetables, soft drinks and other foods. It can be whipped like egg whites, liquefied or gelled and can take on the flavour and texture of a variety of foods. It is 99.5% protein, contains no salt, fat or cholesterol.

Main use

All parts of the plant contain nicotine, which can be extracted and used as an insecticide. The dried leaves can also be used; they remain effective for 6 months after drying. The juice of the leaves can be rubbed on the body as an insect repellent. The leaves can be dried and chewed as an intoxicant. The dried leaves are also used as snuff or are smoked. This is the main species that is used to make cigarettes, cigars, and other products for smokers. A drying oil is obtained from the seed.

Curing and aging

After tobacco is harvested, it is cured (dried), and then aged to improve its flavor. There are four common methods of curing tobacco: air curing, fire curing, flue curing, and sun curing. The curing method used depends on the type of tobacco and its intended use. Air-cured tobacco is sheltered from wind and sun in a well-ventilated barn, where it air dries for six to eight weeks. Air-cured tobacco is low in sugar, which gives the tobacco smoke a light, sweet flavour, and high in nicotine. Cigar and burley tobaccos are air cured.

In fire curing, smoke from a low-burning fire on the barn floor permeates the leaves. This gives the leaves a distinctive smoky aroma and flavor. Fire curing takes three to ten weeks and produces a tobacco low in sugar and high in nicotine. Pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and snuff are fire cured.

Flue-cured tobacco is kept in an enclosed barn heated by flues (pipes) of hot air, but the tobacco is not directly exposed to smoke. This method produces cigarette tobacco that is high in sugar and has medium to high levels of nicotine. It is the fastest method of curing, requiring about a week. Virginia tobacco that has been flue cured is also called bright tobacco, because flue curing turns its leaves gold, orange, or yellow.

Sun-cured tobacco dries uncovered in the sun. This method is used in Greece, Turkey, and other Mediterranean countries to produce oriental tobacco. Sun-cured tobacco is low in sugar and nicotine and is used in cigarettes.

Once the tobacco is cured, workers tie it into small bundles of about 20 leaves, called hands, or use a machine to make large blocks, called bales. The hands or bales are aged for one to three years to improve flavor and reduce bitterness.

Gallery

References

- Ren, Nan; Timko, Michael P. (2001). "AFLP analysis of genetic polymorphism and evolutionary relationships among cultivated and wild Nicotiana species". Genome. 44 (4): 559–71. doi:10.1139/gen-44-4-559. PMID 11550889.

- Wennig, Robert (2009). "Back to the roots of modern analytical toxicology: Jean Servais Stas and the Bocarmé murder case". Drug Testing and Analysis. 1 (4): 153–5. doi:10.1002/dta.32. PMID 20355192.

- Varela, L. G.; Bernays, E. A. (1988-07-01). "Behavior of newly hatched potato tuber moth larvae, Phthorimaea operculella Zell. (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), in relation to their host plants". Journal of Insect Behavior. 1 (3): 261–275. doi:10.1007/BF01054525. ISSN 0892-7553.

- Talhout, R; Opperhuizen, A; van Amsterdam, JG (Oct 2007). "Role of acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke addiction". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 17 (10): 627–36. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013. PMID 17382522.

- Roberts, E.A.H. (1951). "The polyphenols and amino acids of tobacco leaf". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 33 (2): 299–303. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(51)90109-9.

- Zhang, Jianxun; et al. (2007). "Selective Determination of Pyridine Alkaloids in Tobacco by PFTBA Ions/Analyte Molecule Reaction Ionization Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry". Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 18 (10): 1774–1782. doi:10.1016/j.jasms.2007.07.017.

- Pourkhabbaz, Alireza; Pourkhabbaz, Hamidreza (2012). "Investigation of Toxic Metals in the Tobacco of Different Iranian Cigarette Brands and Related Health Issues". Iran J Basic Med Sci. 15 (1): 636–644. PMC 3586865. PMID 23493960.

- Zhang, Xiaotao; Wang, Ruoning; Zhang, Li; Ruan, Yibin; Wang, Weiwei; Ji, Houwei; Lin, Fucheng; Liu, Jian (2018). "Simultaneous determination of tobacco minor alkaloids and tobacco-specific nitrosamines in mainstream smoke by dispersive solid-phase extraction coupled with ultra-performance liquid chromatography/Tandem orbitrap mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 32 (20): 1791–1798. Bibcode:2018RCMS...32.1791Z. doi:10.1002/rcm.8222. PMID 29964303.

- Groark, Kevin P. (2010). "The Angel in the Gourd: Ritual, Therapeutic, and Protective Uses of Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Among the Tzeltal and Tzotzil Maya of Chiapas, Mexico". Journal of Ethnobiology. 30 (1): 5–30. doi:10.2993/0278-0771-30.1.5.

- Otsu, C.T.; Dasilva, I; De Molfetta, JB; Da Silva, LR; De Almeida-Engler, J; Engler, G; Torraca, PC; Goldman, GH; Goldman, MH (2004). "NtWBC1, an ABC transporter gene specifically expressed in tobacco reproductive organs". Journal of Experimental Botany. 55 (403): 1643–54. doi:10.1093/jxb/erh195. PMID 15258165.

External links