Mourning dove

The mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) is a member of the dove family, Columbidae. The bird is also known as the American mourning dove or the rain dove, and erroneously as the turtle dove, and was once known as the Carolina pigeon or Carolina turtledove.[2] It is one of the most abundant and widespread of all North American birds. It is also a leading gamebird, with more than 20 million birds (up to 70 million in some years) shot annually in the U.S., both for sport and for meat. Its ability to sustain its population under such pressure is due to its prolific breeding; in warm areas, one pair may raise up to six broods of two young each in a single year. The wings make an unusual whistling sound upon take-off and landing, a form of sonation. The bird is a strong flier, capable of speeds up to 88 km/h (55 mph).[3] It is the national bird of the British Virgin Islands.

| Mourning dove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mourning Dove vocalizations | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Zenaida |

| Species: | Z. macroura |

| Binomial name | |

| Zenaida macroura | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

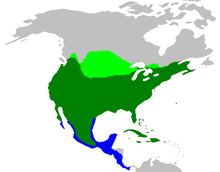

| Summer only range Year-round range Winter only range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Mourning doves are light grey and brown and generally muted in color. Males and females are similar in appearance. The species is generally monogamous, with two squabs (young) per brood. Both parents incubate and care for the young. Mourning doves eat almost exclusively seeds, but the young are fed crop milk by their parents.

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram showing the position of the mourning dove in the genus Zenaida.[4] |

In 1731 the English naturalists Mark Catesby described and illustrated the passenger pigeon and the mourning dove on successive pages of his The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. For the passenger pigeon he used the common name "Pigeon of passage" and the Latin Palumbus migratorius; for the mourning dove he used "Turtle of Carolina" and Turtur carolinensis.[5] In 1743 the naturalist George Edwards included the mourning dove with the English name "long-tail'd dove" and the Latin name Columba macroura in his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Edwards' pictures of the male and female doves were drawn from live birds that had been shipped to England from the West Indies.[6] When in 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition he conflated the two species. He used the Latin name Columba macroura introduced by Edwards as the binomial name but included a description mainly based on Catesby. He cited Edward's description of the mourning dove and Catesby's description of the passenger pigeon.[7][8] Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae again in 1766 for the twelfth edition. He dropped Columba macroura and instead coined Columba migratoria for the passenger pigeon, Columba cariolensis for the mourning dove and Columba marginata for Edwards' mourning dove.[9][8]

To resolve the confusion over the binomial names of the two species, Francis Hemming proposed in 1952 that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) secure the specific name macroura for the mourning dove, and the name migratorius for the passenger pigeon, since this was the intended use by the authors on whose work Linnaeus had based his description.[10] This was accepted by the ICZN, which used its plenary powers to designate the species for the respective names in 1955.[11]

The mourning dove is now placed in the genus Zenaida that was introduced in 1838 by the French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte.[12][13] The genus name commemorates Zénaïde Laetitia Julie Bonaparte, wife of the French ornithologist Charles Lucien Bonaparte and niece of Napoleon Bonaparte. The specific epithet is from the Ancient Greek makros meaning "long" and -ouros meaning "-tailed".[14]

The mourning dove is closely related to the eared dove (Zenaida auriculata) and the Socorro dove (Zenaida graysoni). Some authorities describe them as forming a superspecies and these three birds are sometimes classified in the separate genus Zenaidura,[15] but the current classification has them as separate species in the genus Zenaida. In addition, the Socorro dove has at times been considered conspecific with the mourning dove, although several differences in behavior, call, and appearance justify separation as two different species.[16] While the three species do form a subgroup of Zenaida, using a separate genus would interfere with the monophyly of Zenaida by making it paraphyletic.[15]

There are five subspecies:[13]

- Z. m. marginella (Woodhouse, 1852) – west Canada and west USA to south central Mexico

- Z. m. carolinensis (Linnaeus, 1766) – east Canada and east USA, Bermuda, Bahama Islands

- Z. m. macroura (Linnaeus, 1758) – Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica

- Z. m. clarionensis (Townsend, CH, 1890) – Clarion Island (off west Mexico)

- Z. m. turturilla (Wetmore, 1956) – Costa Rica, west Panama

The ranges of most of the subspecies overlap a little, with three in the United States or Canada.[17] The West Indian subspecies is found throughout the Greater Antilles.[18] It has recently invaded the Florida Keys.[17] The eastern subspecies is found mainly in eastern North America, as well as Bermuda and the Bahamas. The western subspecies is found in western North America, including parts of Mexico. The Panamanian subspecies is located in Central America. The Clarion Island subspecies is found only on Clarion Island, just off the Pacific coast of Mexico.[18]

The mourning dove is sometimes called the "American mourning dove" to distinguish it from the distantly related mourning collared dove (Streptopelia decipiens) of Africa.[15] It was also formerly known as the "Carolina turtledove" and the "Carolina pigeon".[19] The "mourning" part of its common name comes from its call.[20]

The mourning dove was thought to be the passenger pigeon's closest living relative based on morphological grounds[21][22] until genetic analysis showed Patagioenas pigeons to be more closely related. The mourning dove was even suggested to belong to the same genus, Ectopistes, and was listed by some authors as E. carolinensis.[23]

The mourning dove is a related species to the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), which was hunted to extinction in the early 1900s.[24][25][26] For this reason, the possibility of using mourning doves for cloning the passenger pigeon has been discussed.[27]

Description

.jpg)

The mourning dove is a medium-sized, slender dove approximately 31 cm (12 in) in length. Mourning doves weigh 112–170 g (4.0–6.0 oz), usually closer to 128 g (4.5 oz).[28] The elliptical wings are broad, and the head is rounded. Its tail is long and tapered ("macroura" comes from the Greek words for "large" and "tail"[29]). Mourning doves have perching feet, with three toes forward and one reversed. The legs are short and reddish colored. The beak is short and dark, usually a brown-black hue.[17]

The plumage is generally light gray-brown and lighter and pinkish below. The wings have black spotting, and the outer tail feathers are white, contrasting with the black inners. Below the eye is a distinctive crescent-shaped area of dark feathers. The eyes are dark, with light skin surrounding them.[17] The adult male has bright purple-pink patches on the neck sides, with light pink coloring reaching the breast. The crown of the adult male is a distinctly bluish-grey color. Females are similar in appearance, but with more brown coloring overall and a little smaller than the male. The iridescent feather patches on the neck above the shoulders are nearly absent, but can be quite vivid on males. Juvenile birds have a scaly appearance, and are generally darker.[17]

Feather colors are generally believed to be relatively static, changing only by small amounts over periods of months. However, a recent study argues that since feathers are neither innervated nor vascularized, color changes must be caused by external stimuli. Researchers analyzed the ways in which feathers of iridescent mourning doves responded to stimulus changes of adding and evaporating water. As a result, it was discovered that iridescent feather color changed hue, became more chromatic, and increased in overall reflectance by almost 50%. Transmission electron microscopy and transfer matrix thin-film models revealed that color is produced by thin-film interference from a single layer of keratin around the edge of feather barbules, under which lies a layer of air and melanosomes. Once the environmental conditions were changes, the most striking morphological difference was a twisting of colored barbules that exposed more of their surface area for reflection, which explains the observed increase in brightness. Overall, the researchers suggest that some plumage colors may be more changeable than previously thought possible. [30]

All five subspecies of the mourning dove look similar and are not easily distinguishable.[17] The nominate subspecies possesses shorter wings, and is darker and more buff-colored than the "average" mourning dove. Z. m. carolinensis has longer wings and toes, a shorter beak, and is darker in color. The western subspecies has longer wings, a longer beak, shorter toes, and is more muted and lighter in color. The Panama mourning dove has shorter wings and legs, a longer beak, and is grayer in color. The Clarion Island subspecies possesses larger feet, a larger beak, and is darker brown in color.[18]

Vocalization

This species' call is a distinctive, plaintive cooOOoo-woo-woo-woooo, uttered by males to attract females, and may be mistaken for the call of an owl at first. (Close up, a grating or throat-rattling sound may be heard preceding the first coo.) Other sounds include a nest call (cooOOoo) by paired males to attract their mates to the nest sites, a greeting call (a soft ork) by males upon rejoining their mates, and an alarm call (a short roo-oo) by either male or female when threatened. In flight, the wings make a fluttery whistling sound that is hard to hear. The wing whistle is much louder and more noticeable upon take-off and landing.[17]

Distribution and habitat

The mourning dove has a large range of nearly 11,000,000 km2 (4,200,000 sq mi).[31] The species is resident throughout the Greater Antilles, most of Mexico, the Continental United States, southern Canada, and the Atlantic archipelago of Bermuda. Much of the Canadian prairie sees these birds in summer only, and southern Central America sees them in winter only.[32] The species is a vagrant in northern Canada, Alaska,[33] and South America.[15] It has been spotted as an accidental at least seven times in the Western Palearctic with records from the British Isles (5), the Azores (1) and Iceland (1).[17] In 1963, the mourning dove was introduced to Hawaii, and in 1998 there was still a small population in North Kona.[34] The mourning dove also appeared on Socorro Island, off the western coast of Mexico, in 1988, sixteen years after the Socorro dove was extirpated from that island.[16]

The mourning dove occupies a wide variety of open and semi-open habitats, such as urban areas, farms, prairie, grassland, and lightly wooded areas. It avoids swamps and thick forest.[33] The species has adapted well to areas altered by humans. They commonly nest in trees in cities or near farmsteads.

Migration

Most mourning doves migrate along flyways over land. On rare occasions, mourning doves have been seen flying over the Gulf of Mexico, but this appears to be exceptional. Mourning doves (Z. m. carolinensis) are native to the North Atlantic archipelago of Bermuda, approximately 1,044 km (649 mi) east-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (the nearest landfall); 1,236 km (768 mi) south of Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia; and 1,538 km (956 mi) due north of the British Virgin Islands, from which they had been migratory, but since the 1950s have become year-round residents.[35]

Spring migration north runs from March to May. Fall migration south runs from September to November, with immatures moving first, followed by adult females and then by adult males.[32] Migration is usually during the day, in flocks, and at low altitudes.[33] However, not all individuals migrate. Even in Canada some mourning doves remain through winter, sustained by the presence of bird feeders.

Behaviour and ecology

Mourning doves sunbathe or rainbathe by lying on the ground or on a flat tree limb, leaning over, stretching one wing, and keeping this posture for up to twenty minutes. These birds can also waterbathe in shallow pools or bird baths. Dustbathing is common as well.

Outside the breeding season, mourning doves roost communally in dense deciduous trees or in conifers. During sleep, the head rests between the shoulders, close to the body; it is not tucked under the shoulder feathers as in many other species. During the winter in Canada, roosting flights to the roosts in the evening, and out of the roosts in the morning, are delayed on colder days.[36]

Breeding

Courtship begins with a noisy flight by the male, followed by a graceful, circular glide with outstretched wings and head down. After landing, the male will approach the female with a puffed-out breast, bobbing head, and loud calls. Mated pairs will often preen each other's feathers.[33]

The male then leads the female to potential nest sites, and the female will choose one. The female dove builds the nest. The male will fly about, gather material, and bring it to her. The male will stand on the female's back and give the material to the female, who then builds it into the nest.[37] The nest is constructed of twigs, conifer needles, or grass blades, and is of flimsy construction.[18] Mourning doves will sometimes requisition the unused nests of other mourning doves, other birds, or arboreal mammals such as squirrels.[38]

Most nests are in trees, both deciduous and coniferous. Sometimes, they can be found in shrubs, vines, or on artificial constructs like buildings,[18] or hanging flower pots.[37] When there is no suitable elevated object, mourning doves will nest on the ground.[18]

The clutch size is almost always two eggs.[37] Occasionally, however, a female will lay her eggs in the nest of another pair, leading to three or four eggs in the nest.[39] The eggs are white, 6.6 ml (0.23 imp fl oz; 0.22 US fl oz), 2.57–2.96 cm (1.01–1.17 in) long, 2.06–2.30 cm (0.81–0.91 in) wide, 6–7 g (0.21–0.25 oz) at laying (5–6% of female body mass). Both sexes incubate, the male from morning to afternoon, and the female the rest of the day and at night. Mourning doves are devoted parents; nests are very rarely left unattended by the adults.[37] When flushed from the nest, an incubating parent may perform a nest-distraction display, or a broken-wing display, fluttering on the ground as if injured, then flying away when the predator approaches it.

| Hatching and growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Incubation takes two weeks. The hatched young, called squabs, are strongly altricial, being helpless at hatching and covered with down.[37] Both parents feed the squabs pigeon's milk (dove's milk) for the first 3–4 days of life. Thereafter, the crop milk is gradually augmented by seeds. Fledging takes place in about 11–15 days, before the squabs are fully grown but after they are capable of digesting adult food.[38] They stay nearby to be fed by their father for up to two weeks after fledging.[33]

Mourning doves are prolific breeders. In warmer areas, these birds may raise up to six broods in a season.[33] This fast breeding is essential because mortality is high. Each year, mortality can reach 58% a year for adults and 69% for the young.[39]

The mourning dove is monogamous and forms strong pair bonds.[39] Pairs typically reconvene in the same area the following breeding season, and sometimes may remain together throughout the winter. However, lone doves will find new partners if necessary.

Feeding

Like other columbines, the mourning dove drinks by suction, without lifting or tilting its head. It often gathers at drinking spots around dawn and dusk.

Mourning doves eat almost exclusively seeds, which make up more than 99% of their diet.[37] Rarely, they will eat snails or insects. Mourning doves generally eat enough to fill their crops and then fly away to digest while resting. They often swallow grit such as fine gravel or sand to assist with digestion. The species usually forages on the ground, walking but not hopping.[33] At bird feeders, mourning doves are attracted to one of the largest ranges of seed types of any North American bird, with a preference for rapeseed, corn, millet, safflower, and sunflower seeds. Mourning doves do not dig or scratch for seeds, though they will push aside ground litter; instead they eat what is readily visible.[18][37] They will sometimes perch on plants and eat from there.[33]

Mourning doves show a preference for the seeds of certain species of plant over others. Foods taken in preference to others include pine nuts, sweetgum seeds, and the seeds of pokeberry, amaranth, canary grass, corn, sesame, and wheat.[18] When their favorite foods are absent, mourning doves will eat the seeds of other plants, including buckwheat, rye, goosegrass and smartweed.[18]

Predators and parasites

The primary predators of this species are diurnal birds of prey, such as falcons and hawks. During nesting, corvids, grackles, housecats, or rat snakes will prey on their eggs.[39] Cowbirds rarely parasitize mourning dove nests. Mourning doves reject slightly under a third of cowbird eggs in such nests, and the mourning dove's vegetarian diet is unsuitable for cowbirds.[40]

Mourning doves can be afflicted with several different parasites and diseases, including tapeworms, nematodes, mites, and lice. The mouth-dwelling parasite Trichomonas gallinae is particularly severe. While a mourning dove will sometimes host it without symptoms, it will often cause yellowish growth in the mouth and esophagus that will eventually starve the host to death. Avian pox is a common, insect-vectored disease.[41]

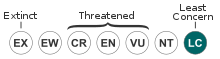

Conservation status

The number of individual mourning doves is estimated to be approximately 475 million.[42] The large population and its vast range explain why the mourning dove is considered to be of least concern, meaning that the species is not at immediate risk.[31] As a gamebird, the mourning dove is well-managed, with more than 20 million (and up to 40–70 million) shot by hunters each year.[43] However, more recent reporting cautions that mourning doves are in decline in the western United States, and susceptible everywhere in the country due to lead poisoning as they eat spent shot left over in hunting fields. In some cases the fields are specifically planted with a favored seed plant to lure them to those sites.[44][45]

As a symbol and in the arts

The eastern mourning dove (Z. m. carolinensis) is Wisconsin's official symbol of peace.[46] The bird is also Michigan's state bird of peace.[47]

The mourning dove appears as the Carolina turtle-dove on plate 286 of Audubon's Birds of America.[19]

References to mourning doves appear frequently in Native American literature. Mourning Dove was the pen name of Christine Quintasket, one of the first published Native American women authors. Mourning dove imagery also turns up in contemporary American and Canadian poetry in the work of poets as diverse as Robert Bly, Jared Carter,[48] Lorine Niedecker,[49] and Charles Wright.[50]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Zenaida macroura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torres, J.K. (1982) The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, p. 730, ISBN 0517032880

- Bastin, E.W. (1952). "Flight-speed of the Mourning Dove". Wilson Bulletin. 64 (1): 47.

- Banks, R.C.; Weckstein, J.D.; Remsen Jr, J.V.; Johnson, K.P. (2013). "Classification of a clade of New World doves (Columbidae: Zenaidini)". Zootaxa. 3669 (2): 184–188. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3669.2.11.

- Catesby, Mark (1731). The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Volume 1. London: W. Innys and R. Manby. pp. 23, 24, Plates 23, 24.

- Edwards, George (1743). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. London: Printed for the author, at the College of Physicians. p. 15 Plate 15.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 164.

- Bangs, O. (1906). "The names of the passenger pigeon and the mourning dove". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 19: 43–44.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1766). Systema naturae: per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1, Part 1 (12th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. pp. 285, 286.

- Hemming, F. (1952). "Proposed use of the plenary powers to secure that the name Columba migratoria Linnaeus, 1766, shall be the oldest available name for the Passenger Pigeon, the type species of the genus Ectopistes Swainson, 1827". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 9: 80–84. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.10238.

- Hemming, Francis, ed. (1955). "Direction 18: Designation under the Plenary Powers of a lectotype for the nominal species Columba macroura Linnaeus, 1758, to secure that that name shall apply to the Mourning Dove and that the name Columba migratoria Linnaeus, 1766, shall be the oldest available name for the Passenger Pigeon (Direction supplementary to Opinion 67)". Opinions and declarations rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Vol 1, Section C Part C.9. London: International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. pp. 113–132.

- Bonaparte, Charles Lucian (1838). A Geographical and Comparative List of the Birds of Europe and North America. London: John Van Voorst. p. 41.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Pigeons". IOC World Bird List Version 10.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 236, 414. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- South American Classification Committee American Ornithologists' Union. "Part 3. Columbiformes to Caprimulgiformes". A classification of the bird species of South America. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved 2006-10-11.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Check-list of North American Birds" (PDF). American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 225. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- Jonathan Alderfer (ed.). National Geographic Complete Birds of North America. p. 303. ISBN 0-7922-4175-4.

- NRCS p. 3

- Audubon, John James. "Plate CCLXXXVVI". Birds of America. ISBN 1-55859-128-1. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- "Pigeon". Encarta Online. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- Blockstein, David E. (2002). "Passenger Pigeon Ectopistes migratorius". In Poole, Alan; Gill, Frank (eds.). The Birds of North America. 611. Philadelphia: The Birds of North America, Inc. p. 4.

- Wilmer J., Miller (16 January 1969). Should Doves be Hunted in Iowa?. The Biology and Natural History of the Mourning Dove. Ames, IA: Ames Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Brewer, Thomas Mayo (1840). Wilson's American Ornithology: with Notes by Jardine; to which is Added a Synopsis of American Birds, Including those Described by Bonaparte, Audubon, Nuttall, and Richardson. Boston: Otis, Broaders, and Company. p. 717.

- Facts Archived 2007-05-07 at the Wayback Machine . Save The Doves. Retrieved on 2013-03-23.

- The Biology and natural history of the Mourning Dove Archived 2012-09-20 at the Wayback Machine. Ringneckdove.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-23.

- The Mourning Dove in Missouri. the Conservation Commission of the State of Missouri (1990) mdc.mo.gov

- Cloning Extinct Species, Part II Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine. Tiger_spot.mapache.org. Retrieved on 2013-03-23.

- Miller, Wilmer J. (1969-01-16). "The biology and Natural History of the Mourning Dove". Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

Mourning doves weigh 4–6 ounces, usually close to the lesser weight.

- Borror, D.J. (1960). Dictionary of Word Roots and Combining Forms. Palo Alto: National Press Books. ISBN 0-87484-053-8.

- Shawkey, Mathew D (April 2011). "Structural color change following hydration and dehydration of iridescent mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) feathers". Zoology. 114 (2): 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2010.11.001. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Birdlife International. "Mourning Dove – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- "Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura)" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management leaflet 31. National Resources Conservation Services (NRCS). February 2006. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin. p. 293. ISBN 0-395-77017-3.

- "Check-list of North American Birds" (PDF). American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 224. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- Mourning Dove, The Bermuda Audubon Society

- Doucette, D.R. & Reebs, S.G. (1994). "Influence of temperature and other factors on the daily roosting times of Mourning Doves in winter". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 72 (7): 1287–90. doi:10.1139/z94-171.

- "Mourning Dove". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- NRCS p. 4

- NRCS p. 1

- Peer, Brian & Bollinger, Eric (1998). "Rejection of Cowbird eggs by Mourning Doves: A manifestation of nest usurpation?" (PDF). The Auk. 115 (4): 1057–62. doi:10.2307/4089523.

- NRCS p. 6

- Mirarchi, R.E., and Baskett, T.S. 1994. Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura). In The Birds of North America, No. 117 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, DC: The American Ornithologists' Union.

- Sadler, K.C. (1993) Mourning Dove harvest. In Ecology and management of the Mourning Dove (T.S. Baskett, M.W. Sayre, R.E. Tomlinson, and R.E. Mirarchi, eds.) Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, ISBN 0811719405.

- "Cornell NestWatch Mourning Dove". NestWatch. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- "United States Geological Survey". www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- Wisconsin Historical Society. "Wisconsin State Symbols". Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- Audi, Tamara (2006-10-16). "Dove hunting finds place on Mich. ballot". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- Carter, Jared (1993) "Mourning Doves" Archived 2003-08-22 at the Wayback Machine , in After the Rain, Cleveland State Univ Poetry Center, ISBN 0914946978

- "Poetry". Friends of Lorine Niedecker. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Meditation on Song and Structure Archived 2008-07-25 at the Wayback Machine from Negative Blue: Selected Later Poems by Charles Wright

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zenaida macroura. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Zenaida macroura |

- Xeno-canto: audio recordings of the mourning dove

- Mourning dove – Zenaida macroura – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Mourning dove Movies (Tree of Life)

- Mourning dove photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)