Mochi

Mochi (Japanese: 餅, もち) is Japanese rice cake made of mochigome, a short-grain japonica glutinous rice, and sometimes other ingredients such as water, sugar, and cornstarch. The rice is pounded into paste and molded into the desired shape. In Japan it is traditionally made in a ceremony called mochitsuki.[1] While also eaten year-round, mochi is a traditional food for the Japanese New Year and is commonly sold and eaten during that time.

Mochi is a multicomponent food consisting of polysaccharides, lipids, protein and water. Mochi has a heterogeneous structure of amylopectin gel, starch grains, and air bubbles.[2] This rice is characterized by its low level of amylose starch, and is derived from short- or medium-grain japonica rices. The protein concentration of the rice is higher than that of normal short-grain rice, and the two also differ in amylose content. In mochi rice, the amylose content is negligible, and the amylopectin level is high, which results in its gel-like consistency.[3]

Mochi is similar to dango, but is made using pounded intact grains of rice, while dango is made of rice flour.[4]

History and origin

The pounding process of making mochi originates from China, where glutinous rice has been grown and used for thousands of years. A number of Aboriginal Chinese tribes have used this process as part of their traditions.[5] In folklore, the first mochitsuki ceremony occurred after the Kami are said to have descended to Earth, which was following the birth of rice cultivation in Yamato during the Yayoi period (300 BC – 300 AD). Red rice was the original variation used in the production of mochi. At this time, it was eaten exclusively by the emperor and nobles due to its status as an omen of good fortune. During the Japanese Heian period (794–1192), mochi was used as a "food for the gods" and in religious offerings in Shinto rituals performed by aristocrats. In addition to general good fortune, mochi was also known as a talisman for happy marriages.

The first recorded accounts of mochi being used as a part of New Year's festivities are from the Japanese Heian period. The nobles of the imperial court believed that long strands of freshly made mochi symbolized long life and well-being, while dried mochi helped strengthen one's teeth. Accounts of it can also be found in the oldest Japanese novel, The Tale of Genji.[6]

Mochi continues to be one of the traditional foods eaten around Japanese New Year, as it is sold and consumed in abundance around this time. A special type, called kagami mochi (mirror mochi), is placed on family altars on December 28 each year. Kagami mochi is composed of two spheres of mochi stacked on top of one another, topped with an orange (daidai). On this occasion, which was originally practiced by the samurai, the round rice cakes of kagami mochi would be broken, thus symbolizing the mirror's opening and the ending of the New Year's celebrations.[7]

Seasonal specialities

New Year

- Kagami mochi is a New Year decoration, which is traditionally broken and eaten in a ritual called kagami biraki (mirror opening).

- Zōni is a soup containing rice cakes. It is also eaten on New Year's Day. In addition to mochi, zōni contains vegetables such as taro, carrot, honeywort, and red and white colored kamaboko.

- Kinako mochi is traditionally made on New Year's Day as an emblem of luck. This style of mochi preparation involves roasting the mochi over a fire or stove, then dipping it into water, finally coating it with sugar and kinako (soy flour).

Spring time

The cherry blossom (sakura), is a symbol of Japan and signifies the onset of full-fledged spring. Sakuramochi is a pink-coloured mochi surrounding sweet anko and wrapped in an edible, salted cherry leaf; this dish is usually made during the spring.[8]

Children's Day

Children's Day is celebrated in Japan on May 5. On this day, the Japanese promote the happiness and well-being of children. Kashiwa-mochi and chimaki are made especially for this celebration.[8] Kashiwa-mochi is white mochi surrounding a sweet anko filling with a Kashiwa oak leaf wrapped around it.[8] Chimaki is a variation of a dango wrapped in bamboo leaves.[8]

Girls' Day

Hishi mochi is a ceremonial dessert presented as a ritual offering on the days leading up to Hinamatsuri or "Girls' Day" in Japan. Hishi mochi is rhomboid-shaped mochi with layers of red, green, and white. The three layers are coloured with jasmine flowers, water caltrop, and mugwort.[9]

Traditional preparation

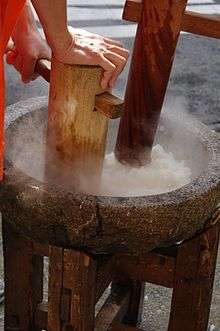

Traditionally, mochi was made from whole rice, in a labor-intensive process. The traditional mochi-pounding ceremony in Japan is mochitsuki:

- Polished glutinous rice is soaked overnight and steamed.

- The steamed rice is mashed and pounded with wooden mallets (kine) in a traditional mortar (usu).[10] The work involves two people, one pounding and the other turning and wetting the substance [11] the mochi.[12] They must keep a steady rhythm or they may accidentally injure each other with the heavy kine.

- The sticky mass can be eaten immediately or formed into various shapes (usually a sphere or cube).[11]

Modern preparation

Mochi is prepared from a flour of sweet rice (mochiko). The flour is mixed with water and cooked on a stovetop or in the microwave until it forms a sticky, opaque, white mass.[13] This process is performed twice, and the mass is stirred in between[14] until it becomes malleable and slightly transparent.[15]

With modern equipment, mochi can be made at home, with the technology automating the laborious dough pounding.[14] Household mochi appliances provide a suitable space where the environment of the dough can be controlled.

The assembly-line sections in mochi production control these aspects:

- Viscoelasticity or the products' chewiness by selecting specific species of rice

- Consistency of the dough during automated pounding process

- Size

- Flavourings and fillings

Varieties of glutinous and waxy rice are produced as major raw material for mochi. The rice is chosen for tensile strength and compressibility. One study found that in Kantomochi rice 172 and BC3, amylopectin distribution varied and affected the hardness of mochi. Kantomochi rice produced harder, brittle, grainy textures, all undesirable qualities except for ease of cutting.[16] For mass production, the rice variety should be chewy, but easy to separate.

Generally, two types of machines are used for mochi production in an assembly line. One machine prepares the dough, while the other forms the dough into consistent shapes, unfilled or with filling. The first type of machine controls the temperature at which the rice gelatinizes. One study found that a temperature of 62 °C corresponds to the gelatinization of mochi. When the temperature fell below 62 °C, the hardening was too slow. It was concluded that a processing temperature below 62 °C was unsuitable for dough preparation.[17]

Processing

Mochi is a variation of a low-calorie, low-fat rice cake. The cake has two essential raw materials, rice and water. Sticky rice (also called sweet rice, Oryza sativa var. glutinosa, glutinous sticky rice, glutinous rice, waxy rice, botan rice, biroin chal, mochi rice, pearl rice, and pulut),[18] whether brown or white, is best for mochi-making, as long-grain varieties will not expand perfectly. Water is essential in the early stages of preparation. Other additives such as salt and other seasonings and flavourings are important in terms of nutritive value and taste. However, additives can cause breakage of the mass, so should not be added to the rice before the cake is formed. The cake must be steamed (rather than boiled) until it gains a smooth and elastic texture. The balls of rice are then flattened, cut into pieces, or shaped into rounds.[11] The machines for mass production are a hugely expensive investment, and the product should have the proper moisture, to appeal to consumers.[19]

Preservation

The best preservation for mochi is refrigeration for a short storage period. For preserving larger batches over an extended time, freezing is recommended. The best method for freezing involves wrapping each mochi cake tightly in a sealed plastic bag. Although mochi can be kept in a freezer for almost one year, the frozen mochi may lose flavor and softness or get freezer-burned.[19]

Ingredients

Mochi is relatively simple to make, as only a few ingredients are needed for plain, natural mochi. The main ingredient is either Shiratamako or Mochiko, Japanese sweet glutinous rice flours. Both Shiratamako and Mochiko are made from mochigome, a type of Japanese glutinous short-grain rice. The difference between Shiratamako and Mochiko comes from texture and processing methods. Shiratamako flour has been more refined and is a finer flour with a smoother, more elastic feel.[20] Mochiko is less refined and has a doughier texture.

Other ingredients may include water, sugar, and cornstarch (to prevent sticking).[21] Additional other ingredients can be added to create different variations/flavors.

Nutrition

The caloric content of a matchbox-sized piece of mochi is comparable to that of a bowl of rice. Japanese farmers were known to consume it during the winter to increase their stamina, while the Japanese samurai took mochi on their expeditions, as it was easy to carry and prepare. Mochi is gluten- and cholesterol-free, as it is made from rice flour.

A single serving of 44.0 g has 96 Calories (kilocalories), 1.0 g of fat, but no trans or saturated fat, 1.0 mg of sodium, 22.0 g of carbohydrates, 0 g of dietary fiber, 6.0 g of sugar, and 1.0 g of protein.[22]

Chemistry and structural composition of glutinous rice

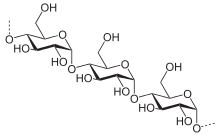

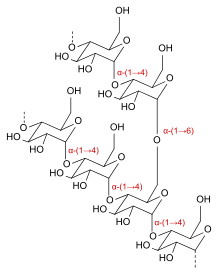

Amylose and amylopectin are both components of starch and polysaccharides made from D-glucose units. The big difference between the two is that amylose is linear because it only has αlpha-1,4-glycosidic bonds. Amylopectin, though, is a branched polysaccharide because it has αlpha-1,4-glycosidic bonds with occasional αlpha-1,6-glycosidic bonds[23] around every 22 D-glucose units.[24] Glutinous rice is nearly 100%[25] composed of amylopectin and almost completely lacks its counterpart, amylose, in its starch granules. A nonglutinous rice grain contains amylose at about 10-30% weight by weight and amylopectin at about 70-90% weight by weight.[23]

Glutinous or waxy type of starches occur in maize, sorghum, wheat, and rice. An interesting characteristic of glutinous rice is that it stains red when iodine is added, whereas nonglutinous rice stains blue.[25] This phenomenon occurs when iodine is mixed with iodide to form tri-iodide and penta-iodide. Penta-iodide intercalates between the starch molecules and stains amylose and amylopectin blue and red, respectively.[26] The gelation and viscous texture of glutinous rice is due to amylopectin being more hygroscopic[27] than amylose, thus water enters the starch granule, causing it to swell, while the amylose leaves the starch granule and becomes part of a colloidal solution.[28] In other words, the higher the amylopectin content, the higher the swelling of the starch granule.[29]

Though the amylopectin content plays a major role in the defined characteristic of viscosity in glutinous rice, factors such as heat also play a very important role in the swelling, since it enhances the uptake of water into the starch granule significantly. The swelling increases at about 10% in volume per 10 °C temperature increase.[30]

The high amylopectin content of waxy or glutinous starches is genetically controlled by the waxy or wax gene. Its quality of greater viscosity and gelation is dependent on the distribution of the amylopectin unit chains.[23] Grains that have this gene are considered mutants, which explains why most of them are selectively bred to create a grain that is close to having or has a 0% amylose content.[25] The table below summarizes the amylose and amylopectin content of different starches, waxy and nonwaxy:

| Starch | Amylose % | Amylopectin % |

| Potato | 20 | 80 |

| Sweet potato | 18 | 82 |

| Arrowroot | 21 | 79 |

| Tapioca | 17 | 83 |

| Corn (maize) | 28 | 72 |

| Waxy maize | 0 | 100 |

| Wheat | 26 | 74 |

| Rice (long grain) | 22 | 78 |

The soaking of the glutinous rice is an elemental step in the preparation of mochi, either traditionally or industrially. During this process, glutinous rice decreases in protein content as it is soaked in water. The chemicals that make up the flavour of plain or "natural" mochi are ethyl ester acetic acid, ethanol, 2-butanol, 2 methyl 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 3-methyl 1 butanol, 1-pentanol and propane acid.[32]

Mochi is usually composed solely of glutinous rice, however, some variations may include the additions of salt, spices and flavourings such as cinnamon (cinnamaldehyde).[33] Food additives such as sucrose, sorbitol or glycerol may be added to increase viscosity and therefore increase gelatinization. Additives that slow down retrogradation are not usually added since amylopectin has a very stable shelf life due to its high amylopectin content.[34]

Viscoelasticity

Mochi's characteristic chewiness is due to the polysaccharides in it. The viscosity and elasticity that account for this chewiness are affected by many factors such as the starch concentration, configuration of the swollen starch granules, the conditions of heating (temperature, heating period and rate of heating) as well as the junction zones that interconnect each polymer chain. The more junction zones the substance has, the stronger the cohesiveness of the gel, thereby forming a more solid-like material. The perfect mochi has the perfect balance between viscosity and elasticity so that it is not inextensible and fragile but rather extensible yet firm.[35]

Many tests have been conducted on the factors that affect the viscoelastic properties of mochi. As puncture tests show, samples with a higher solid (polysaccharide) content show an increased resistance and thereby a stronger and tougher gel. This increased resistance to the puncture test indicate that an increase in solute concentration leads to a more rigid and harder gel with an increased cohesiveness, internal binding, elasticity and springiness which means a decrease in material flow or an increase in viscosity. These results can also be brought about by an increase in heating time.

Sensory assessments of the hardness, stickiness and elasticity of mochi and their relationship with solute concentration and heating time were performed. Similar to the puncture test results, sensory tests determine that hardness and elasticity increase with increasing time of heating and solid concentration. However, stickiness of the samples increase with increasing time of heating and solid concentration until a certain level, above which the reverse is observed.

These relationships are important because too hard or elastic a mochi is undesirable, as is one that is too sticky and will stick to walls of the container.[35]

Health hazards

Suffocation deaths are caused by mochi every year in Japan, especially among elderly people.[36] According to the Tokyo Fire Department which responds to choking cases, mochi sends more than 100 people to the hospital every year in Tokyo alone. Between 2006 and 2009, 18 people died from choking on mochi in the Japanese capital, according to the city's fire department. In 2011, Japanese media reported eight mochi-related deaths in Tokyo in January.

Every year, Japanese authorities warn people to cut mochi into small pieces before eating it. The Tokyo Fire Department even has a website offering tips on how to help someone choking on mochi.[36]

Popular uses

Though mochi is often consumed alone as a major component of a main meal, it is often used as an ingredient in many other prepared foods.

Confectionery

Many types of traditional wagashi and mochigashi (Japanese traditional sweets) are made with mochi. For example, daifuku is a soft round mochi stuffed with sweet filling, such as sweetened red bean paste (anko) or white bean paste (shiro an). Ichigo daifuku is a version containing a whole strawberry inside.[37]

Kusa mochi is a green variety of mochi flavored with yomogi (mugwort). When daifuku is made with kusa mochi, it is called yomogi daifuku.

Ice cream

Small balls of ice cream are wrapped inside a mochi covering to make mochi ice cream. In Japan, this is manufactured by the conglomerate Lotte under the name Yukimi Daifuku, "snow-viewing daifuku".

Soup

- Oshiruko or ozenzai is a sweet azuki bean soup with pieces of mochi. In winter, Japanese people often eat it to warm themselves.

.jpg) A spherical mochi named "dango" can be colored or undyed.

A spherical mochi named "dango" can be colored or undyed. - Chikara udon (meaning "power udon") is a dish consisting of udon noodles in soup topped with toasted mochi.

- Zōni. See New Year specialties below.

Other variations

- Dango is a Japanese dumpling made from mochiko (rice flour).

- Warabimochi is not true mochi, but a jelly-like confection made from bracken starch and covered or dipped in kinako (soybean flour) with sugar. It is popular in the summertime, and often sold from trucks, not unlike ice cream trucks in Western countries.

- Manjū (饅頭,まんじゅう)is not a true mochi, but a popular traditional Japanese confection. Made of flour, rice powder, buckwheat, and red bean paste.

- Yōkan (羊羮) is a thick, jelly-like dessert. It is made of red bean paste, agar, and sugar. There are two main types: Neri yōkan and mizu yōkan.

- More recently, "Moffles" (a waffle made from a toasted mochi) has been introduced.[38] It is made in a specialized machine as well as a traditional waffle iron.

- Sakumochi (索餅) is deep fried rice cake twisted into a rope shape. It is often consumed during the Japanese Star Festival called Tanabata. There is some confusion about its origin based on evidence from historical records of a dish called sakubei (索べい), which some scholars believe was a confection while others think it was an early form of the wheat noodle sōmen. (Sakubei was made from a mixture of wheat flour and rice flour).[39]

Variations outside Japan

In Taiwan, a traditional Hakka and Hoklo pounded rice cake was called tauchi (Chinese: 豆糍; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: tāu-chî) and came in various styles and forms just like in Japan. Traditional Hakka tauchi is served as glutinous rice dough, covered with peanut or sesame powder. Not until the Japanese era was Japanese-style mochi introduced and gain popularity. Nowadays, Taiwanese mochi often comes with bean paste fillings.

In China, tangyuan is made from glutinous rice flour mixed with a small amount of water to form balls and is then cooked and served in boiling water. Tangyuan is typically filled with black sesame paste or peanut paste and served in the water that it was boiled in.

In Hong Kong and other Cantonese regions, the traditional Lo Mai Chi (Chinese: 糯米糍; Jyutping: no6 mai5 ci4) is made of glutinous rice flour in the shape of a ball, with fillings such as crushed peanuts, coconut, red bean paste, and black sesame paste. It can come in a variety of modern flavors such as green tea, mango, taro, strawberry, and more.

In Philippines, a traditional Filipino sweet snack similar to Japanese mochi is called tikoy (Chinese: 甜粿; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: tiⁿ-kóe). There is also another delicacy called espasol with a taste similar to Japanese kinako mochi, though made with roasted rice flour (not kinako, roasted soy flour). The Philippines also has several steamed rice snacks with very similar names to mochi, including moche, mache, and masi. These are small steamed rice balls with bean paste or peanut fillings. However they are not derived from the Japanese mochi, but are derivatives of the Chinese jian dui (called buchi in the Philippines). They are also made with the native galapong process, which mixes ground slightly fermented cooked glutinous rice with coconut milk.

In Korea, chapssal-tteok (Hangul: 찹쌀떡) varieties are made of steamed glutinous rice or steamed glutinous rice flour.

In Indonesia, kue moci is usually filled with sweet bean paste and covered with sesame seeds. Kue Moci comes from Sukabumi, West Java.

In Malaysia, kuih kochi is made from glutinous rice flour and filled with coconut filling and palm sugar. Another Chinese Malaysians variant, loh mai chi is made with same ingredients but their fillings are filled with crushed peanuts.[40] There is also kuih tepung gomak, which has similar ingredients and texture to Mochi but larger in size and the snack was quite popular in the east coast of Malaysia.[41][42]

In Singapore, Muah Chee is made from glutinous rice flour and is usually coated with either crushed peanuts or black sesame seeds.[43]

In Taiwan, a soft version similar to daifuku is called moachi (Chinese: 麻糍; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: moâ-chî) in Taiwanese Hokkien and mashu (Chinese: 麻糬; pinyin: máshǔ) in Taiwanese Mandarin.

In Hawaii, a dessert variety called "butter mochi" is made with butter, sugar, coconut, and other ingredients then baked to make a sponge cake of sorts.

See also

- Arare

- Hishi mochi

- Hanabiramochi

- Muchi

- Senbei, rice crackers

- Uirō

- Japanese rice

Similar foods in other countries:

- Chapssal-tteok, Korean glutinous rice cakes

- Bánh giầy

- Kochi

- Nian gao

- Tteok

References

- "Mochitsuki: A New Year's Tradition". Japanese American National Museum.

- Isono, Yoshinobu; Emiko Okamura; Teruo Fujimoto (1990). "Linear Viscoelastic Properties and Tissue Structures of Mochi Cake". Agric. Biol. Chem. 54 (11): 2941–2947. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.54.2941.

- Bean, M.M; Esser, C.A.; Nishita, K.D. (1984). "Some Physiochemical and Food Application Characteristics of California Waxy Rice Varieties". Cereal Chemists. 61 (6): 475–479.

- The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.

- "打糍粑迎新年". Laifeng. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Itoh, Makiko (30 December 2011). "Rice takes prized, symbolic yearend form". The Japan Times Online. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Caile, Christopher. "Kagami Biraki: Renewing the Spirit". Fighting Arts. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "Japanese confectionery". Travel Around Japan. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Spacey, John. "What is Hishimochi?". Japan Talk. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Okita, Yoko (2015). "Mochitsuki-An International Student Exchange Event Between Juntendo University and Tokyo Medical and Dental University" – via Juntendo University.

- "Processing Rice's Treasures - The Japanese Table - Food Forum Previous Editions - Food Forum - Kikkoman Corporation". www.kikkoman.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- Japan Documentary (2015-04-16), [Begin Japanology] Season 4 EP01 : Mochi Rick Cake 2011-01-13, retrieved 2016-03-18

- "Not-So-Stressful Microwave Mochi". The Fatty Reader.

- "Mochi Making Then and Now". www.discovernikkei.org. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- Itoh, Makiko, "Rice takes prized, symbolic yearend form", Japan Times, 30 December 2011, p. 14.

- Sasaki, Tomoko; Hayakawa, Fumiyo; Suzuki, Yasuhiro; Suzuki, Keitaro; Kazuyuki, Okamoto; Kaoru, Kohyama (2013). "Characterization of Waxy Rice Cakes (Mochi) with Rapid Hardening Quality by Instrumental and Sensory Methods". Cereal Chemistry. 90 (2): 101. doi:10.1094/CCHEM-05-12-0058-R.

- Matsue, Yuji; Uchimura, Yosuke; Sato, Hirokazu (2008). "Estimation of Hardening Speed of "Mochi" of Glutinous Rice from the Gelatinization Temperature, an Amylographic Characteristic, and the Correlation of the Hardening Speed with Gelatinization Temperature and Air Temperature During the Ripening Period(Quality and Processing)". Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 71: 57–61. doi:10.1626/jcs.71.57.

- Schilling, Robert Louis; Schilling, Jennifer (Sep 30, 2014), Method of producing granulated and powdered mochi-like food product and wheat flour substitute, retrieved 2016-03-18

- "How rice cake is made - production process, making, history, processing, parts, components, product, machine, History". www.madehow.com. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- "Shiratamako • Just One Cookbook". Just One Cookbook. 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- "Sweet Mochi Recipe – Japanese Cooking 101". www.japanesecooking101.com. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- "Calories in Japanese Mochi - Calories and Nutrition Facts | MyFitnessPal.com". www.myfitnesspal.com. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- Fredriksson, H et al. (1997). The influence of amylose and amylopectin characteristics on gelatinization and retrogradation properties of different starches. Elsevier Publications, Carbohydrate Polymers. 35, 119-134.

- Ghaeb, Maryam; Tavanai, Hossein; Kadivar, Mehdi (2015). "Electrosprayed maize starch and its constituents (amylose and amylopectin) nanoparticles". Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 26 (8): 917–923. doi:10.1002/pat.3501.

- Bemiller, James N.; Whistler, Roy L. (2009-04-06). Starch: Chemistry and Technology. ISBN 9780080926551.

- "Iodine-Potassium iodide - Solution" (PDF).

- Svagan, Anna. J.; Berglund, Lars A.; Jensen, Poul (2011-04-26). "Cellulose Nanocomposite Biopolymer Foam—Hierarchical Structure Effects on Energy Absorption". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 3 (5): 1411–1417. doi:10.1021/am200183u. PMID 21520887.

- Hermansson, Anne-Marie; Svegmark, Karin (1996-11-01). "Developments in the understanding of starch functionality". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 7 (11): 345–353. doi:10.1016/S0924-2244(96)10036-4.

- Laovachirasuwan, Pornpun; Peerapattana, Jomjai; Srijesdaruk, Voranuch; Chitropas, Padungkwan; Otsuka, Makoto (2010-06-15). "The physicochemical properties of a spray dried glutinous rice starch biopolymer". Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 78 (1): 30–35. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.02.004. PMID 20307959.

- "Dietary carbohydrate composition". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- "07-2: Structure of Starches | CHEM 005". online.science.psu.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- Lee, Yong-Hwan; et al. (2001). "Changes in Chemical Composition of glutinous rice during steeping and Quality Properties of Yukwa". Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- Kilham, Christopher (1996-10-01). The Whole Food Bible: How to Select & Prepare Safe, Healthful Foods. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 9780892816262.

- Ploypetchara, Thongkorn; Suwannaporn, Prisana; Pechyen, Chiravoot; Gohtani, Shoichi (2014-10-22). "Retrogradation of Rice Flour Gel and Dough: Plasticization Effects of Some Food Additives". Cereal Chemistry Journal. 92 (2): 198–203. doi:10.1094/CCHEM-07-14-0165-R. ISSN 0009-0352.

- Kapri, Alka; Suvendu Bhattacharya (2008). "Gelling behavior of rice flour dispersions at different concentrations of solids and time of heating". Journal of Texture Studies. 39 (3): 231–251. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4603.2008.00140.x.

- "Mochi hazards".

- "Ichigo Daifuku".

- Nagata, Kazuaki (19 March 2008). "'Mochi' moffles reinvent the waffle" – via Japan Times Online.

- Ishige, Naomichi. History Of Japanese Food. Routledge. p. 77.

- "Welcome citrusandcandy.com - BlueHost.com". www.citrusandcandy.com.

- Saini, Azimin (20 March 2017). "10 Delicious Traditional Malay Kueh Dissected". Michelin Guide.

- "Resepi Kuih Tepung Gomak Paling Enak" (in Malay). Iluminasi.com. 26 December 2018.

- https://www.youngparents.com.sg/family/best-muah-chee-singapore-families-kids/