Melbourne Airport

Melbourne Airport (IATA: MEL, ICAO: YMML), colloquially known as Tullamarine Airport, is the primary airport serving the city of Melbourne, and the second busiest airport in Australia. It opened in 1970 to replace the nearby Essendon Airport. Melbourne Airport is the main international airport of the four airports serving the Melbourne metropolitan area, the other international airport being Avalon Airport.

Melbourne Airport Melbourne–Tullamarine | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||

| Owner | Leased Commonwealth Airport | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | Australia Pacific Airports Corporation Limited | ||||||||||||||

| Serves | Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Melbourne Airport, Victoria, Australia | ||||||||||||||

| Hub for |

| ||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 434 ft / 132 m | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°40′24″S 144°50′36″E | ||||||||||||||

| Website | melbourneairport | ||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||

MEL  MEL  MEL | |||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2018/2019) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Sources: Australian AIP and aerodrome chart[3] Passengers and aircraftmovements from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics | |||||||||||||||

The airport comprises four terminals: one international terminal, two domestic terminals and one budget domestic terminal. It is 23 kilometres (14 miles) northwest of the city centre, adjacent to the suburb of Tullamarine. The airport has its own suburb and postcode—Melbourne Airport, Victoria (postcode 3045).[4]

In 2016–17 around 25 million domestic passengers and 10 million international passengers used the airport.[5] The Melbourne–Sydney air route is the third most-travelled passenger air route in the world.[6] The airport features direct flights to 33 domestic destinations and to destinations in the Pacific, Europe, Asia, North America and South America. Melbourne Airport is the number one arrival/departure point for the airports of four of Australia's eight other capital cities.[lower-alpha 1] Melbourne serves as a major hub for Qantas and Virgin Australia, while Jetstar Airways and Tigerair Australia utilise the airport as home base. Domestically, Melbourne serves as headquarters for Australian airExpress and Toll Priority and handles more domestic freight than any other airport in the nation.[8]

History

Establishment

Before the opening of Melbourne Airport, Melbourne's main airport was Essendon Airport, which was officially designated an international airport in 1950. In the mid-1950s, over 10,000 passengers were using Essendon Airport, and its limitations were beginning to become apparent. Essendon's facilities were insufficient to meet the increasing demand for air travel; the runways were too short to handle jets, and the terminals failed to handle the increase in passengers. By the mid-1950s, an international overflow terminal was built in a new northern hangar. The airport could not be expanded, as it had become surrounded by residential districts.

The search for a replacement for Essendon commenced in February 1958, when a panel was appointed to assess Melbourne's civil aviation needs.[9]

In 1959, the Commonwealth Government acquired 5,300 ha (13,000 acres) of grassland in then-rural Tullamarine.[10]

In May 1959 it was announced that a new airport would be built at Tullamarine, with Prime Minister Robert Menzies announcing on 27 November 1962 a five-year plan to provide Melbourne with a A$45 million "jetport" by 1967.[11][12][13][14] The first sod at Tullamarine was turned two years later in November 1964.[9] In line with the five-year plan, the runways at Essendon were expanded to handle larger aircraft, with Ansett Australia launching the Boeing 727 there in October 1964, the first jet aircraft used for domestic air travel in Australia.[15][11]

On 1 July 1970, Prime Minister John Gorton opened Melbourne Airport to international operations ending Essendon's near two decade run as Melbourne's international airport.[16] Essendon still was home to domestic flights for one year, until they transferred to Melbourne Airport on 26 June 1971, with the first arrival of a Boeing 747 occurring later that year.[17][18] In the first year of operations, Melbourne handled six international airlines and 155,275 international passengers.[18]

Melbourne Airport was originally called 'Melbourne International Airport'. It is at Tullamarine, a name derived from the indigenous name Tullamareena.[15] Locally, the airport is commonly referred to as Tullamarine or simply as Tulla to distinguish the airport from the other three Melbourne airports: Avalon, Essendon and Moorabbin.[19][20]

On opening, Melbourne Airport consisted of three connected terminals: International in the centre, with Ansett to the South and Trans Australia Airlines to the North. The design capacity of the airport was eight Boeing 707s at a rate of 500 passengers per hour, with minor expansion works completed in 1973 allowing Boeing 747s to serve the airport.[21] By the late 1980s peak passenger flows at the airport had reached 900 per hour, causing major congestion.[21]

In late 1989, Federal Airports Corporation Inspector A. Rohead was put in charge of a bicentennial project to rename streets in Melbourne Airport to honour the original inhabitants, European pioneers and aviation history. Information on the first two categories was provided by Ian Hunter, Wurundjeri researcher, and Ray Gibb, local historian. The project was completed but was shelved, with the only suggested name, Gowrie Park Drive, being allocated, named after the farm at the heart of the airport. During the 1920s, the farm had been used as a landing site for aircraft, which were parked at night during World War II in case Essendon Aerodrome was bombed.[22]

Expansion and privatisation

In 1988, the Australian Government formed the Federal Airports Corporation (FAC), placing Melbourne Airport under the operational control of the new corporation along with 21 other airports around the nation.[18]

The FAC undertook a number of upgrades at the airport. The first major upgrades were carried out at the domestic terminals,[18] with an expansion of the Ansett domestic terminal approved in 1989 and completed in 1991, adding a second pier for use by smaller regional airlines.[23][24] Work on an upgrade of the international terminal commenced in 1991, with the 'SkyPlaza' retail complex completed in late 1993 on a site flanking the main international departure gates.[18] The rest of the work was completed in 1995, when the new three-level satellite concourse was opened at the end of the existing concourse. Diamond shaped and measuring 80 m (260 ft) on each side, the additional 10 aerobridges provided by the expansion doubled the international passenger handing capacity at Melbourne Airport.[25]

In April 1994, the Australian Government announced that all airports operated by FAC would be privatized in several phases.[26] Melbourne Airport was included in the first phase, being acquired by the newly formed Australia Pacific Airports Corporation Limited for $1.3 billion.[18] The transfer was completed on 30 June 1997 on a 50-year long-term lease, with the option for a further 49 years.[27] Melbourne Airport is categorized as a Leased Commonwealth Airport.[28]

Since privatization, further improvements to infrastructure have begun at the airport, including expansion of runways, car parks and terminals. The multi-storey carpark outside the terminal was completed between 1995 and August 1997 at a cost of $49 million, providing 3,100 parking spaces, the majority undercover.[18] This initially four-level structure replaced the previous open air carpark outside the terminal. Work commenced on the six-story 276-room Hilton Hotel (now Parkroyal) above the carpark in January 1999, which was completed in mid-2000 at a cost of $55 million. Expansion of the Qantas domestic terminal was completed in 1999, featuring a second pier and 9 additional aircraft stands.[29]

In December 2000, a fourth passenger terminal opened: the Domestic Express Terminal, located to the south of the main terminal building at a cost of $9 million. It was the first passenger terminal facility to be built at Melbourne Airport since 1971.[30]

Expansion of carparks has also continued with a $40 million project commenced in 2004, doubling the size of the short term carpark with the addition of 2,500 spaces over six levels, along with 1,200 new spaces added to the 5,000 already available in the long term carpark.[31] Revenue from retail operations at Melbourne Airport broke the $100 million mark for the first time in 2004, this being a 100 per cent increase in revenue since the first year of privatization.[31]

In 2005, the airport undertook construction works to prepare the airport for the arrival of the double-decker Airbus A380. The main work was the widening of the main north–south runway by 15 m (49 ft), which was completed over a 29-day period in May 2005.[32] The improvements also included the construction of dual airbridges (Gates 9 and 11) with the ability to board both decks simultaneously to reduce turnaround times, the extension of the international terminal building by 20 m (66 ft) to include new penthouse airline lounges, and the construction of an additional baggage carousel in the arrivals hall. As a result, the airport was the first in Australia to be capable of handling the A380.[33] The A380 made its first test flight into the airport on 14 November 2005.[34] On 15 May 2008, the A380 made its first passenger flight into the airport when a Singapore Airlines Sydney-bound flight was diverted from Sydney Airport because of fog.[35] Beginning services in October 2008, Qantas was the first airline to operate the A380 from the airport, flying nonstop to Los Angeles International Airport twice a week. This was the inaugural route for the Qantas A380.[36]

In March 2006, the airport undertook a 5,000 m2 (54,000 sq ft) expansion of Terminal 2, and the construction of an additional level of airline lounges above the terminal.[37] In 2008 a further 25,000 m2 (270,000 sq ft) expansion of Terminal 2 commenced, costing $330 million with completion in 2011. The works added 5 additional aerobridges on a new passenger concourse, and a new 5,000 m2 (54,000 sq ft) outbound passenger security and customs processing zone.[38]

Terminals

Melbourne Airport's terminals have 68 gates: 53 domestic and 15 international.[39] There are five dedicated freighter parking positions on the Southern Freighter Apron.[40] The current terminal numbering system was introduced in July 2005; they were previously known as Qantas Domestic, International, and South (formerly Ansett Domestic).[41]

Terminal 1

Terminal 1 hosts domestic and regional services for Qantas Group airlines, Qantas and QantasLink (which is located to the northern end of the building). Departures are located on the first floor, while arrivals are located on the ground floor. The terminal has 16 parking bays served by aerobridges; 12 are served by single aerobridges whilst four are served by double aerobridges. There are another five non-aerobridge gates, which are used by QantasLink.

Opened with Melbourne Airport in 1970 for Trans Australia Airlines, the terminal passed to Qantas in 1992 when it acquired the airline. Work on improving the original terminal commenced in October 1997 and was completed in late 1999 at a cost of $50 million, featuring a second pier, stands for 9 additional aircraft, an extended access roadway and the expansion of the terminal.[29][18]

Today, a wide range of shops and food outlets are situated at the end of the terminal near the entrance into Terminal 2. Qantas has a Qantas Club, Business Class and a chairman's lounge in the terminal.[42][43]

Terminal 2

Terminal 2 handles all international, and limited domestic, flights out of Melbourne Airport, and opened in 1970. The terminal has 20 gates with aerobridges. Cathay Pacific, Malaysia Airlines, Qantas (which includes two lounges in Terminal 2, a First lounge and a Business lounge/Qantas Club), Singapore Airlines, Air New Zealand and Emirates all operate airline lounges in the terminal.[43][44]

The international terminal contains works by noted Australian Indigenous artists including Daisy Jugadai Napaltjarri and Gloria Petyarre.[45]

A $330 million expansion programme for Terminal 2 was announced in 2007 and was completed in 2012. The objectives of this project include new lounges and retail facilities, a new satellite terminal, increased luggage capacity and a redesign of customs and security areas.[46] A new satellite terminal features floor-to-ceiling windows offers views of the North-South runway. The new concourse includes three double-decker aerobridges which are gates 16, 18 and 20, each accommodating an A380 aircraft or two smaller aircraft and one single aerobridge. The baggage handling capacity will be increased, and two new baggage carousels will cater to increased A380 traffic.[47]

Although described as a satellite terminal, the terminal building is connected by an above-ground corridor to Terminal 2. Departures take place on the lower deck (similar to the A380 boarding lounges currently in use at Gates 9 and 11), with arrivals streamed on to the first floor to connect with the current first floor arrivals deck. All gates including 18 and 20 are now handling passengers.

Terminal 3

Terminal 3 opened with the airport as the Ansett Australia terminal, but is now owned by Melbourne Airport. Terminal 3 is home to Virgin Australia. It has eleven parking bays served by single aerobridges and eight parking bays not equipped with aerobridges.

An expansion of the terminal was approved in 1989 and completed in 1991 when a second pier was added by Ansett to the south for use by smaller regional airline Kendell.[23][24] The terminal was used exclusively by the Ansett Group for all its domestic activities until its collapse in 2001. It was intended to be used by the "new Ansett", under ownership of Tesna; however, following the Tesna group's withdrawal of the purchase of Ansett in 2002, the terminal was sold back to Melbourne Airport by Ansett's administrators. As a result, Melbourne Airport undertook a major renovation and facelift of the terminal, following which Virgin Australia (then Virgin Blue) moved in from what was then called Domestic Express (now Terminal 4),[48] and has since begun operating The Lounge in the terminal, using the former Ansett Australia Golden Wing Lounge area.[43][49] Regional Express also operates an airline lounge in the terminal.[50] The second pier of T3 was lost to the new T4, out of the ten gates they will be reclaiming three. While the others will be used by Tigerair Australia. Check-In facilities for Virgin Australia will still be in T3.

Terminal 4

Terminal 4 – originally called the Domestic Express or South Terminal – is dedicated to budget airlines and is the first facility of its kind at a conventional airport in Australia. It was originally constructed for Virgin Blue (Virgin Australia) and Impulse Airlines. Virgin Blue eventually moved into Terminal 3 following the demise of Ansett.[51] A$5 million refit began in June 2007[52] along the lines of the budget terminal model at Singapore Changi Airport and Kuala Lumpur International Airport. Lower landing and airport handling fees are charged to airlines due to the basic facilities, lack of jet bridges, and fewer amenities and retail outlets compared to a conventional terminal. However, the terminal is located next to the main terminal building, unlike in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. The terminal was rebuilt by Tiger Airways Australia, which has used it as its main hub since it operated its first domestic flight on 23 November 2007.[53]

Jetstar Airways confirmed its involvement in discussions with Melbourne Airport regarding the expansion of terminal facilities to accommodate for the growth of domestic low-cost services. The expansion of Terminal 4 includes infrastructure to accommodate Tiger Airways Australia and Jetstar Airways flights. The development cost hundreds of millions of dollars.[20] In March 2012, airport officials T4 would break ground that October the same year T4 and they expected completion in July 2014, however they later pushed that date to late August 2015. The facility opened on 18 August 2015. The new T4 terminal is 35,000 m2 (380,000 sq ft) and linked "under one roof" with T3. Terminal 4 is currently used by Tigerair Australia, Regional Express Airlines, Jetstar and Airnorth. In November 2015 Jetstar moved into T4. Three Gates are dedicated to Virgin Australia. Jetstar has triple the number of gates it had at T1.[54]

Southern Freighter Apron

The Southern Freighter Apron has five dedicated freighter parking positions which host 21 dedicated freighter operations a week.[40] In August 1997, the fifth freighter parking position and the apron was extended.[18]

Other facilities

Melbourne Airport is served by four hotels. A Parkroyal Hotel is located 100 m (330 ft) from Terminal 2 atop the multi-level carpark. Work commenced on the six-story 280-room hotel in January 1999 and was completed in mid-2000.[29] The hotel was originally a Hilton but was relaunched as the Parkroyal on 4 April 2011.[55] Holiday Inn has an outlet located 400 m (1,300 ft) from the terminal precinct. Ibis Budget offers lodgings located 600 m (2,000 ft) from the terminals. Mantra Tullamarine opened in 2009, 2 km (1.2 mi) from the terminal precinct.[56]

Operations

Overview

Melbourne is the second busiest airport in Australia. The airport is curfew-free and operates 24 hours a day, although between 2 am and 4 am, freight aircraft are more prevalent than passenger flights.[57] In 2004, the environmental management systems were accredited ISO 14001, the world's best practice standard, making it the first airport in Australia to receive such accreditation.[58]

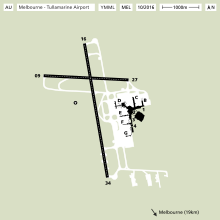

Runways

Melbourne Airport has two intersecting runways: one 3,657 m (11,998 ft) north–south and one 2,286 m (7,500 ft) east–west. Due to increasing traffic, several runway expansions are planned, including an 843 m (2,766 ft) extension of the north-south runway to lengthen it to 4,500 m (14,764 ft), and a 1,214 m (3,983 ft) extension of the east–west runway to a total of 3,500 m (11,483 ft). Two new runways are also planned: a 3,000 m (9,843 ft) runway parallel to the current north–south runway and a 3,000 m (9,843 ft) runway south of the current east–west runway.[59] The current east west runway extension and new third runway were expected to cost $500–750 million with major construction originally set to begin around 2019 and be complete by 2022.[60] However, in 2019 following an extensive consultation period, Melbourne Airport unexpectedly dropped plans for a new east-west runway in favour of constructing a new parallel north-south runway to the west of the airport, citing aircraft noise concerns for residents in nearby suburbs of Gladstone Park, Westmeadows, Attwood and Jacana.[61] Although there is an additional 12–24 months of planning, Melbourne Airport Corporation anticipates the new north-south runway will be operational by 2025, with the potential to include the extension of the existing east-west runway.[62] Traffic movement was expected to reach 248,000 per annum by 2017, and existing runway capacity is expected by 2023, necessitating a third runway.[63]

On 5 June 2008, it was announced that the airport would install a Category III landing system, allowing planes to land in low visibility conditions, such as fog. This system was the first of its kind in Australia, and was commissioned March 2010 at a cost of $10 million.[64][9]

Melbourne Airspace Control Centre

In addition to the onsite control tower, the airport is home to Melbourne Centre, an air traffic control facility that is responsible for the separation of aircraft in Australia's busiest flight information region (FIR), Melbourne FIR. Melbourne FIR monitors airspace over Victoria, Tasmania, southern New South Wales, most of South Australia, the southern half of Western Australia and airspace over the Indian and Southern Ocean. In total, the centre controls 6% of the world's airspace.[65] The airport is also the home of the Canberra, Adelaide and Melbourne approach facilities, which provide control services to aircraft arriving and departing at those airports.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Air Canada | Seasonal: Vancouver[66] |

| Air China | Beijing–Capital |

| Air India | Delhi |

| Air New Zealand | Auckland, Christchurch, Queenstown, Wellington |

| Air Vanuatu | Port Vila[67] |

| Aircalin | Nouméa[68] |

| Airnorth | Toowoomba Wellcamp[69] |

| Beijing Capital Airlines | Qingdao |

| Cathay Pacific | Hong Kong |

| Cebu Pacific | Manila[70] |

| China Airlines | Taipei–Taoyuan[71] |

| China Eastern Airlines | Shanghai–Pudong |

| China Southern Airlines | Guangzhou, Shenzhen[72] |

| Emirates | Dubai–International, Singapore |

| Etihad Airways | Abu Dhabi |

| Fiji Airways | Nadi |

| Garuda Indonesia | Denpasar, Jakarta–Soekarno-Hatta |

| Hainan Airlines | Changsha,[73] Haikou |

| Japan Airlines | Tokyo–Narita[74] |

| Jetstar Airways | Adelaide, Auckland, Ayers Rock,[75] Ballina, Bangkok–Suvarnabhumi, Brisbane, Cairns, Christchurch, Darwin, Denpasar, Gold Coast, Ho Chi Minh City,[76] Hobart, Honolulu, Launceston, Newcastle, Perth, Phuket, Proserpine,[77] Queenstown, Sunshine Coast, Sydney, Townsville |

| LATAM Chile | Santiago de Chile[78] |

| Malaysia Airlines | Kuala Lumpur–International |

| Malindo Air | Denpasar, Kuala Lumpur–International[79] |

| Philippine Airlines | Manila |

| Qantas | Adelaide, Alice Springs, Auckland, Brisbane, Broome, Cairns, Canberra, Christchurch, Darwin, Denpasar,[80] Gold Coast,[81] Hamilton Island,[77] Hobart, Hong Kong, London–Heathrow, Los Angeles, Perth, San Francisco, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo–Haneda,[82] Wellington Seasonal: Queenstown[83] |

| QantasLink | Canberra, Devonport, Launceston, Mildura |

| Qatar Airways | Doha |

| Regional Express Airlines | Albury, Burnie–Wynyard, King Island, Merimbula, Mildura, Mount Gambier, Wagga Wagga |

| Royal Brunei Airlines | Bandar Seri Begawan |

| Scoot | Singapore |

| Sichuan Airlines | Chengdu,[84] Guiyang[85] |

| Singapore Airlines | Singapore, Wellington[86] |

| SriLankan Airlines | Colombo–Bandaranaike[87] |

| Thai Airways | Bangkok–Suvarnabhumi |

| Tianjin Airlines | Chongqing |

| Tigerair Australia | Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra,[88] Coffs Harbour (ends 27 April 2020),[89] Gold Coast, Hobart, Perth, Sydney |

| United Airlines | Los Angeles, San Francisco |

| Vietnam Airlines | Ho Chi Minh City |

| Virgin Australia | Adelaide, Auckland, Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra, Christchurch, Darwin, Denpasar,[90] Gold Coast, Hamilton Island, Hobart, Launceston, Los Angeles,[91] Mildura, Nadi, Newcastle, Perth, Queenstown,[92] Sunshine Coast, Sydney Seasonal: Kununurra (begins 15 May 2020)[93] |

| Virgin Australia Regional Airlines | Kalgoorlie–Boulder |

| XiamenAir | Hangzhou, Xiamen |

Cargo

The following airlines operate cargo-only services from Melbourne Airport's Southern Freighter Apron:

| Airline | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Cathay Pacific Cargo | Hong Kong, Sydney, Toowoomba Wellcamp |

| Kalitta Air Cargo | Cincinnati, Honolulu, Shenzhen, Sydney |

| Qantas Freight | Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra, Gold Coast, Hobart, Launceston, Perth, Sydney |

| Singapore Airlines Cargo | Auckland, Singapore, Sydney |

| Toll Priority | Adelaide, Brisbane, Launceston, Perth, Sydney, Sydney–Bankstown |

Traffic and statistics

In 2016-17 Melbourne Airport recorded around 25 million domestic passenger movements and around 10 million international passenger movements.[5] In that year there were 239,466 aircraft movements in total.[94] Melbourne is the second busiest airport in Australia for passenger movements, behind Sydney and ahead of Brisbane.

| Year | Domestic passengers | International passengers | Domestic aircraft movements^ | International aircraft movements^ | Passengers per domestic aircraft | Passengers per international aircraft |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985-86 | 5,275,067 | 1,200,916 | 74,622 | 11,769 | 71 | 102 |

| 1990-91 | 6,669,030 | 1,677,295 | 86,320 | 15,884 | 77 | 106 |

| 1995-96 | 10,878,097 | 2,093,722 | 116,795 | 15,616 | 93 | 134 |

| 2000-01 | 13,628,580 | 3,252,430 | 151,769 | 22,894 | 90 | 142 |

| 2005-06 | 16,787,596 | 4,253,268 | 150,222 | 25,213 | 112 | 169 |

| 2010-11 | 21,749,355 | 6,213,479 | 173,769 | 33,029 | 125 | 188 |

| 2011-12 | 21,298,613 | 6,657,880 | 171,340 | 34,576 | 124 | 193 |

| 2012-13 | 22,504,752 | 6,987,506 | 179,494 | 35,920 | 125 | 195 |

| 2013-14 | 22,229,895 | 7,666,124 | 183,484 | 39,344 | 127 | 195 |

| 2014-15 | 23,524,659 | 8,410,941 | 187,140 | 41,294 | 126 | 204 |

| 2015-16 | 24,426,026 | 9,278,934 | 190,955 | 43,819 | 128 | 212 |

| 2016-17 | 24,928,048 | 9,949,458 | 191,662 | 45,202 | 130 | 220 |

^ Passenger service movements only (excludes freight).

|

|

|

|

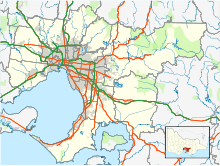

Ground transport

Road

Melbourne Airport is 23 km (14 mi) from the city centre and is accessible via the Tullamarine Freeway. One freeway offramp runs directly into the airport grounds, and a second to the south serves freight transport, taxis, buses and airport staff.[97] In June 2015, the Airport Drive extension was completed, creating a second major link to the airport. The link starts at the M80 Western Ring Road and provides direct access to Melrose Drive 1.5 kilometres from the terminal area.[98] As of 2018 the Tullamarine Freeway is being widened.[99]

Melbourne Airport has five car parks, all of which operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The short-term, multi-level long-term, business and express carparks are covered, while the long-term parking is not.[100] The main multi-level carpark in front of the terminal was built in the late 1990s, replacing the pre-existing ground-level car parking.[29] It has been progressively expanded ever since.

Melbourne Airport recorded more than 2.2 million taxi movements in the year to 30 June 2017.[101]

Public transport

Buses and shuttle services

The Skybus Super Shuttle operates express bus services from the airport to Southern Cross railway station (on the western boundary of the Melbourne City Centre)[102] and St Kilda.[103] Shuttle services also operate between the airport and the Mornington Peninsula,[104] making stops in St Kilda, Elsternwick, Brighton and Frankston.[105] SkyBus current transports around 3.4 million passengers between the airport and Melbourne's CBD.[106]

Metropolitan and regional public buses also operate to or via the airport. Routes 478, 479 & 482 operate to Westfield Airport West, via the route 59 tram terminus. Route 479 also operate to Sunbury railway station, connecting with Sunbury and Bendigo line trains. The route 901 SmartBus service was introduced in September 2010[107] as a frequent bus service.[108] Route 901 connects to trains at Broadmeadows (Craigieburn, Seymour, Shepparton and Albury lines), Epping (Mernda line), Greensborough (Hurstbridge line) and Blackburn (Belgrave and Lilydale lines).[109] V/Line operates timetabled regional coach services to Barham and Deniliquin via the airport.

There are nine other bus companies serving the airport, with services to Ballarat, Bendigo, Dandenong, Frankston, Mornington Peninsula, Geelong, Melbourne's suburbs, Shepparton and the Riverina.[110] These provide alternatives to transfer onto other V/Line services.

Proposed rail connection

Although Melbourne Airport is serviced by public transport vehicles, there is no railway connection between the airport and the city as of 2019.

The possibility of installing a rail link from what was originally known as the Broadmeadows line (now the Craigieburn line) to the airport was debated in the 1960s under the Bolte State Government, but with not enough support in parliament to gain a majority, the rail project was abandoned in 1965.[111]

In 2001, the Bracks State Government investigated the construction of a heavy rail link to the airport under the Linking Victoria programme. Two options were considered; the first branched off the Craigieburn Suburban Line to the east, and the second branched off the Albion Goods Line, which passes close to the airport's boundary to the south. The second option was preferred.[112] Market research concluded most passengers preferred travelling to the airport by taxi or car, and poor patronage of similar links in Sydney and Brisbane cast doubt on the viability of the project.[113] This led to the project being deferred until at least 2012. On 21 July 2008, the Premier of Victoria reaffirmed the government's commitment to a rail link and said that it would be considered within three to five years.[114] To maximise future development options, the airport lobbied for the on-grounds section of the railway to be underground.[59][115]

In 2010, Martin Pakula of the Labor Party, newly appointed State Minister for Public Transport, announced that the rail link had been taken off the agenda with new freeway options being explored instead,[111][116] however a change of government at the 2010 Victorian State Election to Liberals, saw policy for the introduction of the rail link return to the agenda, with a promise by the incoming Coalition government to undertake planning for its construction.[117]

Proposals in January 2013 to improve the bus service to the airport involving turning emergency lanes into bus lanes on the freeway and the Bolte Bridge and putting SkyBus on a myki fare, were challenged by CityLink operator Transurban, because it would limit its toll revenue, and by Melbourne Airport, because it would reduce its car parking profits.[118] Similar objections would apply to a rail link.

On 13 March 2013, the Victorian Liberal government under then Premier, Denis Napthine, announced that the Melbourne Airport Rail Link (MARL) would be constructed around 2015/16 running from the CBD via Sunshine station and the Albion–Jacana railway line.[119] This proposal never became a reality, with the Napthine Government losing office to the Labor Party at the 2014 state election.

In 2015 and 2016, the Andrews state government decided to shelve the airport rail link proposal and instead focus on inner-city rail projects such as the Melbourne Metro Rail Project. But after enormous pressure from the coalition federal governments of Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull to plan for a proposal, the Andrews Government announced in May 2017 that it would spend $10 million along with the Turnbull Government's $30 million to devise a rail link planning study. On 23 November 2017, Premier Daniel Andrews told business groups that construction on a rail link between the airport and Melbourne's Southern Cross station via Sunshine station would begin construction within the next 10 years.[120]

On 12 April 2018, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced that the federal government would pledge $5 billion for a rail link between the airport and Melbourne's CBD. He had also stated that the Victoria state government would also have to match federal funding in order for the project to proceed.[121] With a 50-50 funding split between the State and Federal governments, a possible private investment in the project could see the total cost rise to $15 billion.[122] On 22 July 2018, the state government announced that it would provide $5 billion to match federal government funding for the airport rail link.[123]

On 14 March 2019, the Victorian and Commonwealth governments formally signed off on the project and have committed up to $5 billion each to deliver the missing rail link, with the total cost of the project estimated to be in the range of $8–13 billion. The Sunshine route was chosen for the route of the rail link as it would perform better overall. The Sunshine station will also be upgraded making it easier for metropolitan and regional passengers travelling to and from the airport. Construction of the rail link will take up to nine years and is due to commence in 2022 with the business case to be delivered by 2020.

Accidents and incidents

- On 29 May 2003, Qantas Flight 1737 from Melbourne to Launceston Airport was subjected to an attempted hijacking shortly after takeoff. The hijacker, a passenger named David Robinson, intended to fly the aircraft into the Walls of Jerusalem National Park, located in central Tasmania. The flight attendants and passengers successfully subdued and restrained the hijacker, and the aircraft returned to Melbourne.[124][125]

- On 20 March 2009, Emirates Airline Flight 407, an Airbus A340-500, was taking off from Melbourne Airport on Runway 16 for a flight to Dubai International Airport and failed to become airborne in the normal distance. When the aircraft was nearing the end of the runway, the crew commanded nose-up sharply, causing its tail to scrape along the runway as it became airborne, during which smoke was observed in the cabin. The crew dumped fuel and returned to the airport. The damage caused to the aircraft was considered substantial. The aircraft damaged a strobe light at the end of the runway as well as an antenna on the localiser, which led to the ILS being out of service for some time causing some disruptions to the airport's operation.[126]

Awards and accolades

Melbourne Airport has received numerous awards. The International Air Transport Association ranked Melbourne among the top five airports in the world in 1997 and 1998.[127][128] In 2003, Melbourne received the IATA's Eagle Award for service and two National Tourism Awards for tourism services.[129][130][131]

The airport has received recognition in other areas. It has won national and state tourism awards,[130][131] and Singapore Airlines presented the airport with the Service Partner Award and Premier Business Partner Award in 2002 and 2004, respectively.[128][132] In 2006, the airport won the Australian Construction Achievement Award for the runway widening project, dubbed "the most outstanding example of construction excellence for 2006".[133] In 2012, Parkroyal Melbourne Airport was awarded for the best airport hotel in Australia/the Pacific by Skytrax.[134] According to Skytrax World's Top 100 Airports List, Melbourne Airport has improved from ranked 43rd in 2012 to 27th in 2018.[135][136]

See also

- City of Keilor – the former local government area of which Melbourne Airport was a part

- List of airports in Victoria

- Transport in Australia

Notes

References

- "Melbourne Airport passenger performance FY19".

- "Melbourne airport – Economic and social impacts". Ecquants. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- YMML – Melbourne (PDF). AIP En Route Supplement from Airservices Australia, effective 27 February 2020, Aeronautical Chart Archived 10 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Suburbs in postcode 3045 – Australia Post Codes". Auspostcode.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Airport traffic data: 1985-86 to 2016-17". Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "60th Edition of IATA World Air Transport Statistics".

- "Australian Domestic Aviation Activity 2017-18". Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE). September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "2003 Annual Report" (PDF). Melbourne Airport. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "2010 Annual Report" (PDF). Melbourne Airport. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Lucas, Clay (26 June 2010). "Melbourne Airport train link derailed by buck-passing". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011.

- "Melbourne to Get Jetport in 5-Year Development Plan". The New York Times. 27 November 1962. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "12,000-Car Melbourne Jam". The New York Times. 29 June 1970. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "Approval Given For New Melbourne Airport". The Canberra Times. 34 (9, 553). 18 March 1960. p. 4. Retrieved 13 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Spending on two airports will be increased to £32m". The Canberra Times. 39 (11, 120). 2 April 1965. p. 3. Retrieved 13 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Essendon Airport, Tullamarine Fwy, Strathmore, VIC, Australia (Place ID 102718)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "Tullamarine—a city's pride". The Canberra Times. 44 (12, 664). 2 July 1970. p. 11. Retrieved 13 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Essendon Airport History". City of Moonee Valley. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- "1997–1998 Annual Report" (PDF). Melbourne Airport. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Moynihan, Stephen (13 July 2007). "Tiger bites into fares, but Tulla bleeds". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Murphy, Mathew (19 May 2008). "Jetstar bid for Tulla expansion". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Eames, Jim (1 January 1998). Reshaping Australia's Aviation Landscape: The Federal Airports Corporation 1986–1998. Focus Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1875359479.

- Federal Airports Corporation documents, "Bulla Bulla" I.W. Symonds, the late Harry Heaps and Wally Mansfield

- "Anderson approves new Melbourne Airport terminal" (Press release). minister.infrastructure.gov.au. 15 April 2000. Archived from the original on 28 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Domestic Multi-User Terminal For Melbourne Great For Competition" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. 26 August 2002. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- Eames 1998, p. 55.

- Frost & Sullivan (25 April 2006). "Airport Privatisation". MarketResearch.com. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- Jim Eames (1998). Reshaping Australia's Aviation Landscape: The Federal Airports Corporation 1986–1998. Focus Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 1-875359-47-8.

- Leased Federal Airports, Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (accessed 4 September 2014)

- "1999 Annual Report" (PDF). Australia Pacific Airports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "New Domestic Express Terminal Opens at Melbourne Airport" (Press release). Australian Infrastructure Fund. 5 December 2000. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "2004 Annual Report" (PDF). Australia Pacific Airports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Australia Pacific Airports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "Melbourne – Australia's first fully A380-ready city" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. 10 November 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Barnes, Renee (14 November 2005). "The Airbus has landed". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- "Seven News Melbourne". Seven News. Episode 2008-05-15. 15 May 2008.

- "The Qantas A380 – Now on sale" (Press release). Qantas. 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "2006 Annual Report" (PDF). Australia Pacific Airports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Australia Pacific Airports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "Melbourne Airport – Technical". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport – the hub for freight in Australasia" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport renames terminals" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Qantas Club Locations". Qantas. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport – Airline Lounges". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Etihad Airways' new premium lounge opens at Melbourne airport" (Press release). Etihad Airways. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Battersby, Jean (1996). "Art and Airports 2". Craft Arts International. 37: 49–64.

- Masanauskas, John (27 August 2007). "More space promised in Melbourne airport facelift". Herald Sun. Melbourne. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "$330m Expansions to Melbourne's International Terminal" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. 25 August 2007. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- "Virgin Blue and Melbourne Airport Reach Terminal Deal" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. 23 July 2002. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "The Lounge Pricing". Virgin Blue. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Rex Lounge". Regional Express. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- "Domestic Multi-User Terminal For Melbourne Great For Competition". Melbourne Airport Media Releases. 26 August 2002. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Platt, Craig (8 October 2007). "Tiger offers more discount fares". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Murphy, Mathew (3 May 2007). "Fares to fall as city sinks its claws into Tiger". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "T4 You". Melbourne Airport. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Parkroyal returns to Melbourne with new GM". Hospitality. Australia. 4 April 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Melbourne Airport – Hotels". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Melbourne Flight summary" (PDF). Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport – Environment". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "2008 Draft Master Plan" (PDF). Melbourne Airport. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport plans $500m third runway for 2018-2022".

- "Melbourne Airport's long-awaited third runway could change direction". The Age.

- "Residents fear 'deafening' noise from third Melbourne Airport runway". The Age.

- Dunn, Mark (21 December 2007). "New runways plan for Melbourne Airport". Herald Sun. Melbourne. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Murphy, Mathew; Burgess, Matthew (5 June 2008). "Plan to fog-proof Melbourne Airport". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Centre". Airservices Australia. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- https://www.executivetraveller.com/news/air-canada-melbourne-vancouver-flights-go-seasonal

- "Air Vanuatu announces new Melbourne flights". Air Vanuatu. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Aircalin returning to MEL". Travel Daily. 19 December 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Airnorth Expands from Wellcamp with New Townsville Flights" (Press release). Airnorth. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Cebu Pacific to fly direct Manila-Melbourne route starting August 2018". Cebu Pacific. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- "China Airlines to Start Melbourne Service from late-Oct 2015". Routes Online. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/289245/china-southern-febmar-2020-long-haul-inventory-adjustment-as-of-02feb20/

- Liu, Jim (10 September 2016). "Hainan Airlines plans Changsha – Melbourne launch in Nov 2016". Routes Online. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Liu, Jim (26 May 2017). "JAL proposes Melbourne launch in Sep 2017". Routes Online. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Jetstar to launch Melbourne-Uluru service". Travel Weekly. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Vietnam Just a bargain away with Jetstar to offer direct flights". Herald Sun. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Qantas and Jetstar Boost Queensland Flying" (Press release). Qantas. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Flynn, David (5 December 2016). "LATAM to fly Melbourne-Santiago from October 2017". Australian Business Traveller. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Liu, Jim (29 March 2018). "Malindo Air files Melbourne June 2018 launch". Routes Online. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Qantas Announces Daily Melbourne-Bali Service Launch" (Press release). Qantas. 7 February 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Chamberlain, Chris (22 July 2015). "Qantas to start Melbourne-Gold Coast flights from October". Australian Business Traveller. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Qantas takes off to Tokyo's Haneda and Sapporo" (Press release). Qantas. 16 December 2019.

- "Get Your Skis On: Qantas Launches Direct Flights From Melbourne to Queenstown" (Press release). Qantas. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/289327/sichuan-airlines-febmar-2020-long-haul-changes-as-of-0200gmt-05feb20/

- Liu, Jim (21 April 2019). "Sichuan Airlines plans Guiyang – Melbourne launch in late-May 2019". Routes Online. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "SIA To Launch Melbourne-Wellington Services And Daily Flights To Canberra" (Press release). Singapore Airlines. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Liu, Jim (29 May 2017). "SriLankan Airlines resumes Melbourne service from Oct 2017". Routes Online. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Knaus, Christopher (22 August 2016). "Cheap flights to Melbourne return, Tigerair announces daily route". Canberra Times. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Virgin Australia Group fleet and network changes". Virgin Australia. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- https://www.9news.com.au/national/virgin-australia-group-cuts-routes-and-retires-aircraft-after-business-review/c62429ee-f793-47b5-bdc1-629bb3c07e2a?ref=BP_RSS_ninenews_5_virgin-australia-cuts-routes--retires-planes_061119

- "Melbourne - Los Angeles and Perth - Abu Dhabi flights". Virgin Australia Blog (Press release). 20 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Virgin Australia launches Queenstown, Wellington flights". Australian Business Traveller. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Direct flights Melbourne to Kununurra commence 2020". Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- "Movements at Australian airports: Financial Year 2017". Airservices Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Australian International Airline Activity". Aviation Statistics. Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics. October 2011. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "International Airline Activity 2018". bitre.gov.au. June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "Second Airport entry road opens" (Press release). Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "CityLink Tulla Widening". Victorian Government. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Melbourne Airport – Parking". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "UberX at Melbourne Airport". Melbourne Airport. 15 August 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Melbourne City Express". Skybus. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "St Kilda Express". Skybus. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "Frankston & Peninsula Airport Shuttle". Skybus. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "Locations - Frankston and Peninsula Airport Shuttle". Skybus. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "About SkyBus". SkyBus. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "SmartBus Route 901". The Victorian Transport Plan. transport.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Metro Trains Melbourne (21 September 2010). "New SmartBus direct to Melbourne Airport". metrotrains.com.au. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- "Airport buses". Public Transport Victoria. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "Other Bus Services – To and From the Airport". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- Lucas, Clay (1 March 2010). "Airport road won't cope with demand, study shows". The Age. Melbourne, Australia.

- "Melbourne Airport Rail Link Not Viable Now" (Press release). Minister for Transport. 18 January 2002. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Why can't this train get us to the airport?". The Age. Melbourne. 4 June 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "Surge in passenger demand prompts call for Airport rail link". Herald Sun. Australia. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- Ferguson, John (29 April 2008). "Melbourne airport seeks underground train line". Herald Sun. Melbourne. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Lucas, Clay (12 November 2009). "New airport link proposed". The Age. Melbourne, Australia.

- Troeth, Simon (15 November 2010). "COALITION WILL PLAN MELB AIRPORT RAIL LINK". Liberal Party Victoria. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.

- SkyBus lane faces fight The Age 4 January 2013

- "Route chosen for Melbourne airport link". Perth Now. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Willingham, Richard (23 November 2017). "Melbourne Airport rail link building to start within decade, Premier Daniel Andrews says". ABC News. Melbourne.

- Willingham, Richard (12 April 2018). "Melbourne Airport train link: Malcolm Turnbull pledges $5 billion for long-awaited rail line to CBD". ABC News. Melbourne.

- Cooper, Luke (12 April 2018). "Turnbull government to pledge $5 billion in Federal Budget for new Melbourne Airport rail line". Nine News. Melbourne.

- Noel Towell, "Melbourne airport rail up and away with Andrews government $5b pledge.", The Age, 22 July 2018

- "Two stabbed in attempted hijack over Melbourne". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 May 2003. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- "Qantas hijacker found not guilty". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 14 July 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- "AO-2009-012: Tail strike, Airbus Industrie, A340-541, A6-ERG, Melbourne Airport, Vic, 20 March 2009". Australian Transportation Safety Bureau (Press release). 20 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Melbourne Airport Voted in Top 5 World Airports". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 20 April 1998. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport – Awards". Melbourne Airport. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne's Airport – A World Class Operator". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 3 June 2003. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport Wins Australian Tourism Award". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 16 October 1998. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Second Major Australian Tourism Award for Melbourne Airport". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 1 December 2000. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Melbourne Airport awarded by Singapore Airlines". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 25 June 2004. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Runway widening project wins major Aust. construction award". Melbourne Airport Media Releases (Press release). 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "PARKROYAL Melbourne Airport is voted the Best Airport Hotel in Australia/Pacific region by customers". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- "The World's Top Airports". Archived from the original on 22 November 2012.

- "World's Top 100 Airports 2018". 28 February 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Melbourne Airport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Melbourne Airport. |

- Official website

- Accident history for MEL at Aviation Safety Network