Liriodendron tulipifera

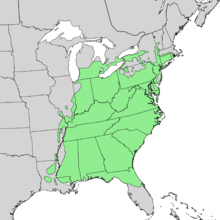

Liriodendron tulipifera—known as the tulip tree, American tulip tree, tulipwood, tuliptree, tulip poplar, whitewood, fiddletree, and yellow-poplar—is the North American representative of the two-species genus Liriodendron (the other member is Liriodendron chinense), and the tallest eastern hardwood. It is native to eastern North America from Southern Ontario and possibly southern Quebec to Illinois eastward to southwestern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and south to central Florida and Louisiana. It can grow to more than 50 m (160 ft) in virgin cove forests of the Appalachian Mountains, often with no limbs until it reaches 25–30 m (80–100 ft) in height, making it a very valuable timber tree.

| Liriodendron tulipifera | |

|---|---|

| Liriodendron tulipifera cultivated at Laken Park in Belgium | |

| |

| L. tulipifera flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Magnoliaceae |

| Genus: | Liriodendron |

| Species: | L. tulipifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Liriodendron tulipifera | |

| |

| Range | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

| |

It is fast-growing, without the common problems of weak wood strength and short lifespan often seen in fast-growing species. April marks the start of the flowering period in the Southern United States (except as noted below); trees at the northern limit of cultivation begin to flower in June. The flowers are pale green or yellow (rarely white), with an orange band on the tepals; they yield large quantities of nectar. The tulip tree is the state tree of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Description

The tulip tree is one of the largest of the native trees of the eastern United States, known to reach the height of 191.8 feet (58.49 meters)[4] with a trunk 1–2 m (4–6 ft) in diameter; its ordinary height is 20 to 40 m (70 to 141 ft). It prefers deep, rich, and rather moist soil; it is common, though not abundant, nor is it solitary. Its roots are fleshy. Growth is fairly rapid, and the typical form of its head is conical.[5]

The bark is brown, and furrowed. The branchlets are smooth, and lustrous, initially reddish, maturing to dark gray, and finally brown. Aromatic and bitter. The wood is light yellow to brown, and the sapwood creamy white; light, soft, brittle, close, straight-grained. Specific gravity: 0.4230; density: 422 g/dm3 (26.36 lb/cu ft).

- Winter buds: Dark red, covered with a bloom, obtuse; scales becoming conspicuous stipules for the unfolding leaf, and persistent until the leaf is fully grown. Flower-bud enclosed in a two-valved, caducous bract.

The alternate leaves are simple, pinnately veined, measuring five to six inches long and wide. They have four lobes, and are heart-shaped or truncate or slightly wedge-shaped at base, entire, and the apex cut across at a shallow angle, making the upper part of the leaf look square; midrib and primary veins prominent. They come out of the bud recurved by the bending down of the petiole near the middle bringing the apex of the folded leaf to the base of the bud, light green, when full grown are bright green, smooth and shining above, paler green beneath, with downy veins. In autumn they turn a clear, bright yellow. Petiole long, slender, angled.

- Flowers: May. Perfect, solitary, terminal, greenish yellow, borne on stout peduncles, an inch and a half to two inches long, cup-shaped, erect, conspicuous. The bud is enclosed in a sheath of two triangular bracts which fall as the blossom opens.

- Calyx: Sepals three, imbricate in bud, reflexed or spreading, somewhat veined, early deciduous.

- Corolla: Cup-shaped, petals six, two inches long, in two rows, imbricate, hypogynous, greenish yellow, marked toward the base with yellow. Somewhat fleshy in texture.

- Stamens: Indefinite, imbricate in many ranks on the base of the receptacle; filaments thread-like, short; anthers extrorse, long, two-celled, adnate; cells opening longitudinally.

- Pistils: Indefinite, imbricate on the long slender receptacle. Ovary one-celled; style acuminate, flattened; stigma short, one-sided, recurved; ovules two.

- Fruit: Narrow light brown cone, formed from many samaras which are dispersed by wind, leaving the axis persistent all winter. September, October.[5]

A description from Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them by Harriet Louise Keeler:[5]

The leaves are of unusual shape and develop in a most peculiar and characteristic manner. The leaf-buds are composed of scales as is usual, and these scales grow with the growing shoot. In this respect the buds do not differ from those of many other trees, but what is peculiar is that each pair of scales develops so as to form an oval envelope which contains the young leaf and protects it against changing temperatures until it is strong enough to sustain them without injury. When it has reached that stage the bracts separate, the tiny leaf comes out carefully folded along the line of the midrib, opens as it matures, and until it becomes full grown the bracts do duty as stipules, becoming an inch or more in length before they fall. The leaf is unique in shape, its apex is cut off at the end in a way peculiarly its own, the petioles are long, angled, and so poised that the leaves flutter independently, and their glossy surfaces so catch and toss the light that the effect of the foliage as a whole is much brighter than it otherwise would be. The flowers are large, brilliant, and on detached trees numerous. Their color is greenish yellow with dashes of red and orange, and their resemblance to a tulip very marked. They do not droop from the spray but sit erect. The fruit is a cone 5 to 8 cm (2 to 3 in) long, made of a great number of thin narrow scales attached to a common axis. These scales are each a carpel surrounded by a thin membranous ring. Each cone contains sixty or seventy of these scales, of which only a few are productive. These fruit cones remain on the tree in varied states of dilapidation throughout the winter.

Liriodendron tulipifera "tulip" flower

Liriodendron tulipifera "tulip" flower Liriodendron tulipifera golden autumn leaves and seed cones

Liriodendron tulipifera golden autumn leaves and seed cones Liriodendron tulipifera, large gray-green flower bud with yellow bract

Liriodendron tulipifera, large gray-green flower bud with yellow bract Liriodendron tulipifera seeds

Liriodendron tulipifera seeds Tulip tree, unfolding leaves

Tulip tree, unfolding leaves Tulip tree leaf

Tulip tree leaf Leaves of 'Aureomarginatum'

Leaves of 'Aureomarginatum'- Liriodendron columnar trunk in streambank woods, North Carolina

_buds_in_spring_06.jpg) Early spring buds opening

Early spring buds opening Yellow poplar leaf with naturally camouflaged, nearly identical-looking imperial moth

Yellow poplar leaf with naturally camouflaged, nearly identical-looking imperial moth Yellow poplar leaf

Yellow poplar leaf

Taxonomy and naming

Originally described by Carl Linnaeus, Liriodendron tulipifera is one of two species (see also L. chinense) in the genus Liriodendron in the magnolia family. The name Liriodendron is Greek for "lily tree".[6] It is also called the tuliptree Magnolia, or sometimes, by the lumber industry, as the tulip-poplar or yellow-poplar. However, it is not closely related to true lilies, tulips or poplars.

The tulip tree has impressed itself upon popular attention in many ways, and consequently has many common names. The tree's traditional name in the Miami-Illinois language is "oonseentia". Native Americans so habitually made their dugout canoes of its trunk that the early settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains called it Canoewood. The color of its wood gives it the name Whitewood. In areas near the Mississippi River it is called a poplar largely because of the fluttering habits of its leaves, in which it resembles trees of that genus. It is sometimes called "fiddle tree," because its peculiar leaves, with their arched bases and in-cut sides, suggest the violin shape.[7]

The external resemblance of its flowers to tulips named it the Tulip-tree.[5] In their internal structure, however, they are quite different. Instead of the triple arrangements of stamens and pistil parts, they have indefinite numbers arranged in spirals.[8]

Distribution and habitat

One of the largest and most valuable hardwoods of eastern North America, it is native from Connecticut and southern New York, westward to southern Ontario and northern Ohio, and south to Louisiana and northern Florida.[9] It is found sparingly in New England, it is abundant on the southern shore of Lake Erie and westward to Illinois. It extends south to north Florida, and is rare west of the Mississippi River, but is found occasionally for ornamentals. Its finest development is in the Southern Appalachian mountains, where trees may exceed 50 m (170 ft) in height. It was introduced into Great Britain before 1688 in Bishop Compton's garden at Fulham Palace and is now a popular ornamental in streets, parks, and large gardens.[10] The Appalachian Mountains and adjacent Piedmont running south from Pennsylvania to Georgia contained 75 percent of all yellow-poplar growing stock in 1974.[11]

Ecology

Liriodendron tulipifera is generally considered to be a shade-intolerant species that is most commonly associated with the first century of forest succession. In Appalachian forests, it is a dominant species during the 50–150 years of succession, but is absent or rare in stands of trees 500 years or older. One particular group of trees survived in the grounds of Orlagh College, Dublin for 200 years, before having to be cut down in 1990.[12] On mesic, fertile soils, it often forms pure or nearly pure stands. It can and does persist in older forests when there is sufficient disturbance to generate large enough gaps for regeneration.[13] Individual trees have been known to live for up to around 500 years.[14]

All young tulip trees and most mature specimens are intolerant of prolonged inundation; however, a coastal plain swamp ecotype in the southeastern United States is relatively flood-tolerant.[15] This ecotype is recognized by its blunt-lobed leaves, which may have a red tint. Liriodendron tulipifera produces a large amount of seed, which is dispersed by wind. The seeds typically travel a distance equal to 4–5 times the height of the tree, and remain viable for 4–7 years. The seeds are not one of the most important food sources for wildlife, but they are eaten by a number of birds and mammals.[16]

Vines, especially wild grapevines, are known to be extremely damaging to young trees of this species. Vines are damaging both due to blocking out solar radiation, and increasing weight on limbs which can lead to bending of the trunk and/or breaking of limbs.[16]

Host plant

In terms of its role in the ecological community, L. tulipifera does not host a great diversity of insects, with only 28 species of moths associated with the tree.[17] Among specialists, L. tulipifera is the sole host plant for the caterpillars of C. angulifera , a giant silkmoth found in the eastern United States.[18] Several generalist species use L. tulipifera. It is as a well-known host for the large, green eggs of the female Papilio glaucus, the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail butterfly, which are known to lay their eggs exclusively among plants in the Magnolia and Rose families of plants, primarily in mid-late June through early August, in some states.[19][20]

East Central Florida ecotype

Parts of east-central Florida near Orlando have an ecotype with similar-looking leaves to the coastal plain variant of the Carolinas; it flowers much earlier (usually in March, although flowering can begin in late January), with a smaller yellower bloom than other types. This east central Florida ecotype/Peninsular allozyme group seems to have the best ability to tolerate very wet conditions, where it may grow short pencil-like root structures (pneumatophores) similar to those produced by other swamp trees in warm climates. Superior resistance to drought, pests and wind is also noted. Some individuals retain their leaves all year unless a hard frost strikes. Places where it may be seen include Dr. Howard A. Kelly Park, Lake Eola Park, Spring Hammock Preserve, Big Tree Park home of The Senator (tree) and the University of Central Florida Arboretum.

Cultivation and use

Liriodendron tulipifera grows readily from seeds, which should be sown in a fine soft mould, and in a cool and shady situation. If sown in autumn they come up the succeeding spring, but if sown in spring they often remain a year in the ground. Loudon says that seeds from the highest branches of old trees are most likely to germinate. It is readily propagated from cuttings and easily transplanted.[5]

In landscaping

Tulip trees make magnificently shaped specimen trees, and are very large, growing to about 35 m (110 ft) in good soil. They grow best in deep well-drained loam which has thick dark topsoil. They show stronger response to fertilizer compounds (those with low salt index are preferred) than most other trees, but soil structure and organic matter content are more important. In the wild it is occasionally seen around serpentine outcrops.[21] The southeastern coastal plain and east central Florida ecotypes occur in wet but not stagnant soils which are high in organic matter. All tulip trees are unreliable in clay flats which are subject to ponding and flooding.

Like other members of the Magnolia family, they have fleshy roots that are easily broken if handled roughly. Transplanting should be done in early spring, before leaf-out; this timing is especially important in the more northern areas. Fall planting is often successful in Florida. The east central Florida ecotype may be more easily moved than other strains because its roots grow over nine or ten months every year—several months longer than other ecotypes. Most tulip trees have low tolerance of drought, although Florida natives (especially the east central ecotype) fare better than southeastern coastal plain or northern inland specimens.

It is recommended as a shade tree.[5] The tree's tall and rapid growth is a function of its shade intolerance. Grown in the full sun, the species tends to grow shorter, slower, and rounder, making it adaptable to landscape planting. In forest settings, most investment is made in the trunk (i.e., the branches are weak and easily break off, a sign of axial dominance) and lower branches are lost early as new, higher branches closer to the sun continue the growth spurt upward. A tree just 15 years old may already reach 12 m (40 ft) in height with no branches within reach of humans standing on the ground.

Cultivars

- 'Ardis' – dwarf, with smaller leaves than wild form. Leaves shallow-lobed, some without lower lobes.

- 'Arnold' – narrow, columnar crown; may flower at early age.

- 'Aureomarginatum' – variegated form with pale-edged leaves; sold as 'Flashlight' or 'Majestic Beauty'.

- 'Fastigatum' – similar form to 'Arnold' but flowers at later age.

- 'Florida Strain' – blunt-lobed leaves, fast grower, flowers at early age.

- 'Integrifolium' – leaves without lower lobes.

- 'JFS-Oz' – compact oval form with straight leader, leaves dark and glossy; sold as 'Emerald City.'

- 'Leucanthum' – flowers white or nearly white.

- 'Little Volunteer' – almost as diminutive as 'Ardis' but with stronger form. Leaves more deeply lobed than 'Ardis.'

- 'Mediopictum' – variegated form with yellow spot near center of leaf.

- 'Roothaan' – blunt-lobed leaves.

In the UK the species[22] and its variegated cultivar 'Aureomarginatum'[23] have both gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[24]

Liriodendron tulipifera has been introduced to many temperate parts of the world, at least as far north as Sykkylven, Norway and Arboretum Mustila, Finland.[25][26] A few nurseries in Finland offer this species even though it is not fully hardy there and tends to be held to shrub form.[27][28]

Honey

This tree species is a major honey plant in the eastern United States, yielding a dark reddish, fairly strong honey which gets mixed reviews as a table honey but is favorably regarded by bakers; nectar is produced in the orange part of the flowers.[29]

Wood

The soft, fine-grained wood of tulip trees is known as "poplar" (short for "yellow-poplar") in the U.S., but marketed abroad as "American tulipwood" or by other names. It is very widely used where a cheap, easy-to-work and stable wood is needed. The sapwood is usually a creamy off-white color. While the heartwood is usually a pale green, it can take on streaks of red, purple, or even black; depending on the extractives content (i.e. the soil conditions where the tree was grown, etc.). It is clearly the wood of choice for use in organs, due to its ability to take a fine, smooth, precisely cut finish and so to effectively seal against pipes and valves. It is also commonly used for siding clapboards. Its wood may be compared in texture, strength, and softness to white pine.

Used for interior finish of houses, for siding, for panels of carriages, for coffin boxes, pattern timber, and wooden ware. During scarcity of the better qualities of white pine, tulip wood has taken its place to some extent, particularly when very wide boards are required.

It also has a reputation for being resistant to termites, and in the Upland South (and perhaps elsewhere) house and barn sills were often made of tulip poplar beams.

Arts

The tulip tree has been referenced in many poems and the namesakes of other poems, such as William Stafford's "Tulip Tree."[30] It is also a plot element in the Edgar Allan Poe short story "The Gold-Bug".[31]

Another form of art that the tulip tree is a major part of is wood carving. The tulip poplar can be very useful and has been one of the favorite types of trees for wood carving by sculptors such as Wilhelm Schimmel and Shields Landon Jones.[32][33]

History

In the Cretaceous age the genus was represented by several species, and was widely distributed over North America and Europe. Its remains are also found in Tertiary rocks.[5]

See also

- The Queens Giant, a tulip tree that is the oldest living thing in the New York Metropolitan area (350–450 years old, 40 m or 130 ft tall)

- Spathodea campanulata, often known as the African tulip tree, an unrelated plant in a separate family (Bignoniaceae).

References

- Rivers, M.C. (2014). "Liriodendron tulipifera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T194015A2294401. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T194015A2294401.en.

- Tropicos

- "The Plant List". The Plant List. 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "Landmark Trees". May 6, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 14–19.

- "Nature Ramblings". Science News-Letter. 59 (19): 300. 12 May 1951. doi:10.2307/3928783. JSTOR 3928783.

- "Nature Ramblings". Science News-Letter. 79 (24): 384. 17 June 1961. doi:10.2307/3942819. JSTOR 3942819.

- "Nature Ramblings". Science News-Letter. 67 (19): 302. 7 May 1955. doi:10.2307/3934969. JSTOR 3934969.

- "Tulip tree." McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006. Credo Reference. Web. 26 September 2012.

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/3294280/Branch-lines-the-tulip-tree.html

- Beck, Donald E. (1990). "Liriodendron tulipifera L." (PDF). http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/USDAFSSilvics/54.pdf. Magnoliaceae: 406–416. External link in

|journal=(help) - 'Knocklyn Past and Present', p. 33

- Busing, Richard T. (1 January 1995). "Disturbance and the Population Dynamics of Liriodendron Tulipifera: Simulations with a Spatial Model of Forest Succession" (PDF). Journal of Ecology. 83 (1): 45–53. doi:10.2307/2261149. JSTOR 2261149.

- "Eastern OLDLIST: A database of maximum tree ages for Eastern North America". Ldeo.columbia.edu. 1972-12-15. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- Parks, Clifford R.; Wendel, Jonathan F.; Sewell, Mitchell M.; Qiu, Yin-Long (1 January 1994). "The Significance of Allozyme Variation and Introgression in the Liriodendron tulipifera Complex (Magnoliaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 81 (7): 878–889. doi:10.2307/2445769. JSTOR 2445769.

- Beck, Donald E. (1990). "Liriodendron tulipifera". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2. Retrieved 2014-04-07 – via Southern Research Station (www.srs.fs.fed.us).

- "HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants - Search Liriodendron tulipifera | National History Museum". www.nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Species Callosamia angulifera - Tulip-Tree Silkmoth | BugGuide". www.bugguide.org. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- Holland, W. J. (1905). The Moth Book: A Popular Guide to a Knowledge of the Moths of North America. New York: Doubleday, Page and Company. pp. 85–86.

- "Tigers on the Wind: The Eastern Tiger Swallowtail". United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)--U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- http://www.coacommunity.net/downloads/serpentine08/serpentinegeoecology.pdf

- "RHS Plant Selector – Liriodendron tulipifera". Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "RHS Plant Selector – Liriodendron tulipifera 'Aureomarginatum'". Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 60. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Tulipantre – Liriodendron tulipifera". Flickr – Photo Sharing!.

- http://www.mustila.fi/en/plants/liriodendron/tulipifera

- http://www.niittytila.com/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=202

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-02-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Plants 4 Bees :: Magnoliaceae :: F267Liriodendron_tulipifera".

- Stafford, William. Stories That Could Be True. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. Print.

- "The Gold-Bug" – Full text from the Dollar Newspaper, 1843 (with two illustrations by F. O. C. Darley)

- "SCHIMMEL, WILHELM (1817–1890)." The Encyclopedia of American Folk Art. London: Routledge, 2003. Credo Reference. Web. 26 September 2012.

- "JONES, SHIELDS LANDON (1901–1997)." The Encyclopedia of American Folk Art. London: Routledge, 2003. Credo Reference. Web. 26 September 2012.

Further reading

- Hunt, D. (ed). 1998. Magnolias and their allies. International Dendrology Society & Magnolia Society. (ISBN 0-9517234-8-0)

- Repopulation of the Tulip Poplar in Central Florida

- Michigan Bee Plants :: Magnoliaceae :: Liriodendron tulipifera

- Archaeanthus: Paleontologists Identify Ancient Ancestor of Tulip Tree by Enrico de Lazaro (September 13, 2013)

External links