Junior Eurovision Song Contest

The Junior Eurovision Song Contest (French: Concours Eurovision de la Chanson Junior),[1] often shortened to JESC, Junior Eurovision or Junior EuroSong, is a song competition which has been organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) annually since 2003 and is open exclusively to broadcasters that are members of the EBU.[2] It is held in a different European city each year, however the same city can host the contest more than once.

| Junior Eurovision Song Contest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also known as | Junior Eurovision JESC Junior EuroSong |

| Genre | Song contest |

| Created by | Bjørn Erichsen |

| Based on | MGP Nordic |

| Presented by | List of presenters |

| Country of origin | List of countries |

| Original language(s) | English and French |

| No. of episodes | 17 contests |

| Production | |

| Production location(s) | List of host cities |

| Running time | 1 hours, 45 minutes (2003) 2 hours (2009–2013) 2 hours, 15 minutes (2005–2008, 2017) 2 hours, 30 minutes (2014–2016, 2018–present) |

| Production company(s) | European Broadcasting Union |

| Distributor | Eurovision |

| Release | |

| Picture format | 576i (SDTV) (2003–present) 1080i (HDTV) (2008–present) |

| Original release | 15 November 2003 – present |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | Eurovision Song Contest (1956-2019 2021-) Eurovision Young Musicians (1982–) Eurovision Young Dancers (1985–2017) Eurovision Dance Contest (2007–2008) Eurovision Magic Circus Show (2010–2012) Eurovision Choir (2017–) |

| External links | |

| Official website | |

| Production website | |

The competition has many similarities to the Eurovision Song Contest from which its name is taken. Each participating broadcaster sends an act, the members of which are aged 9 to 14 on the day of the contest,[3] and an original song lasting between 2 minutes 45 seconds and 3 minutes[2] to compete against the other entries. Each entry represents the country served by the participating broadcaster. Viewers from the participating countries are invited to vote for their favourite performances by televote and a national jury from each participating country also vote.[2] The overall winner of the contest is the entry that has received the most points after the scores from every country have been collected and totalled. The current winner is Viki Gabor of Poland, who won the 2019 contest in Gliwice, Poland with "Superhero".

In addition to the countries taking part, the 2003 contest was also broadcast in Estonia, Finland and Germany,[4] followed by Andorra in 2006 and Bosnia and Herzegovina (from 2006 to 2011), however these countries have yet to participate. Since 2006, the contest has been streamed live on the Internet through the official website of the contest.[5] Australia was invited in the 2015 contest, while Kazakhstan was invited in the 2018 contest, and as of 2019, both countries have participated every year since.

Origins and history

The origins of the contest date back to 2000 when Danmarks Radio held a song contest for Danish children that year and the following year.[6][7] The idea was extended to a Scandinavian song festival in 2002, MGP Nordic, with Denmark, Norway and Sweden as participants.[8][9] The EBU picked up the idea for a song contest featuring children and opened the competition to all EBU member broadcasters making it a pan-European event. The working title of the programme was "Eurovision Song Contest for Children",[10] branded with the name of the EBU's already popular song competition, the Eurovision Song Contest. Denmark was asked to host the first programme after their experience with their own contests and the MGP Nordic.

After a successful first contest, the second faced several location problems. The event originally should have been organised by British broadcaster ITV in Manchester.[11] ITV then announced that due to financial and scheduling reasons, the contest would not take place in the United Kingdom after all.[12] It is also thought that another factor to their decision was the previous years' audience ratings for ITV which were below the expected amount.[13] The EBU approached Croatian broadcaster HRT, who had won the previous contest, to stage the event in Zagreb;[14] though it later emerged that HRT had 'forgotten' to book the venue in which the contest would have taken place.[15] It was at this point, with five months remaining until the event would be held, that Norwegian broadcaster NRK stepped in to host the contest in Lillehammer.[15]

Broadcasters have had to bid for the rights to host the contest since 2004 to avoid such problems from happening again. Belgium was therefore the first country to successfully bid for the rights to host the contest in 2005.[16]

All contests have been broadcast in 16:9 widescreen and in high definition.[4] All have also had a CD produced with the songs from the show. Between 2003 and 2006, DVDs of the contest were also produced though this ended due to lack of interest.[17]

As of 2008, the winner of the contest is decided by 50% televote and 50% national jury vote. The winners of all previous contests had been decided exclusively by televoting. Between 2003 and 2005 viewers had around 10 minutes to vote after all the songs had been performed.[18] Between 2006 and 2010 the televoting lines were open throughout the programme.[19] Since 2011 viewers vote after all the songs had been performed.[20] Profits made from the televoting during the 2007 and 2008 contests were donated to UNICEF.[21]

Prior to 2007, a participating broadcaster's failure in not broadcasting the contest live would incur a fine. Now broadcasters are no longer required to broadcast the contest live, but may transmit it with some delay at a time that is more appropriate for children's television broadcast.[22]

The 2007 contest was the subject of the 2008 documentary Sounds Like Teen Spirit: A Popumentary. The film followed several contestants as they made their way through the national finals and onto the show itself.[23] It was shown at the Toronto International Film Festival 2008[24] and was premiered in Ghent, Belgium[25] and Limassol, Cyprus[26] where the 2008 contest was held.

Format

The format of the contest has remained relatively unchanged over the course of its history in that the format consists of successive live musical performances by the artists entered by the participating broadcasters. The EBU claims that the aim of the programme is "to promote young talent in the field of popular music, by encouraging competition among the [...] performers".[3]

The programme was always screened on a Saturday night in late November/early December and lasts approximately two hours fifteen minutes.[3] Since 2016, the contest is screened on an early Sunday evening.

Traditionally the contest will consist of an opening ceremony in which the performers are welcomed to the event, the performances of the entries, a recap of the songs to help televoting viewers decide which entries to vote for, an interval act usually performed after the televoting has closed, the results of the televoting or back-up jury voting which is then followed by the declaration of the winner and a reprise of the winning song. At various points throughout the show, networks may opt out for a few minutes to screen a commercial break.

Since 2008 the winning entry of each contest has been decided by a mixture of televoting and national juries, each counting for fifty percent of the points awarded by each country.[27] The winners of all previous contests had been decided exclusively by televoting. The ten entries that have received the most votes in each country are awarded points ranging from one to eight, then ten and twelve.[28] These points are then announced live during the programme by a spokesperson representing the participating country (who, like the participants, is aged between ten and fifteen). Once all participating countries have announced their results, the country that has received the most points is declared the winner of that year's contest.

Until 2013 the winners receive a trophy and a certificate.[2] Since 2013 contest the winner, runner-up and third place all win trophies and certificates.[29]

Originally, unlike its adult version, the winning country did not receive the rights to host the next contest. From 2014 until 2017, the winning country had first refusal on hosting the following contest. Italy used this clause in 2015 to decline hosting the contest that year after their victory in 2014. On 15 October 2017, the EBU announced a return to the original system in 2018, claiming that it would help provide broadcasters with a greater amount of time to prepare, ensuring the continuation of the contest into the future.[30]

The contest usually features two presenters, one man and one woman[31][32] (though the 2006,[33] 2014,[34] 2015[35] and 2017 contests were exceptions to this), who regularly appear on stage and with the contestants in the green room. The presenters are also responsible for repeating the results immediately after the spokesperson of each broadcaster to confirm which country the points are being given to. Between 2003 and 2012, the spokespersons gave out the points in the same format as the adult contest, behind a backdrop of a major city of that country in the national broadcaster’s television studio. From 2013 onwards, the spokespersons give the points from their country on the arena stage, as opposed to the adult contest where spokespersons are broadcast live from their respective country.[36] The reason for this is unknown, but it’s believed that with the introduction of new countries, e.g. Australia, the times zones are different. Since JESC is broadcast on a Sunday afternoon, if the spokespersons gave the votes in their respective countries, it would be early morning in Australia, and nobody would want to present the votes.

Despite the Junior Eurovision Song Contest being modelled on the format of the Eurovision Song Contest, there are many distinctive differences that are unique to the children's contest. For instance, while the main vocals must be sung live during the contest, backing vocals may be recorded onto the backing track.[37] Each country's entry must be selected through a televised national final (unless circumstances prevent this and permission is gained from the EBU).[38] Each country's performance is also allowed a maximum of eight performers on stage, as opposed to the original number of six in the Eurovision Song Contest. From 2005 to 2015 every contestant was automatically awarded 12 points to prevent the contestants scoring zero points, although ending with 12 points total was in essence the same as receiving zero,[36] however, no entry has ever received the infamous "nul points".

Entry restrictions

The song must be written and sung in the national language (or one of the national languages) of the country being represented. However, they can also have a few lines in a different language. The same rule was in the adults' contest from 1966 to 1972 and again from 1977 to 1998. Performers must be nationals of that country or have lived there for at least two years.

Originally the competition was open to children between the ages of 8 and 15,[18] however in 2007 the age range was narrowed so that only children aged 10 to 15 on the day of the contest were allowed to enter.[3] In 2016 the age range was changed again. From now on children aged 9 to 14 on the day of the contest are allowed to enter.

The song submitted into the contest cannot have previously been released commercially and must last between 2 minutes 45 seconds and 3 minutes (as of 2013 onwards).[2] The rule stating that performers also must not have previously released music commercially was active from 2003 to 2006.[38] This rule was dropped in 2007 thus allowing already experienced singers and bands in the competition. As a result, NRK chose to withdraw from the contest.[37]

Since 2008, adults have been allowed to assist in the writing of entries.[37] Previously, all writers had to be aged 10 to 15.

Organisation

The contest is produced each year by the European Broadcasting Union. The original executive supervisor of the contest was Svante Stockselius who also headed the "Steering Group" that decides on the rules of the contest, which broadcaster hosts the next contest and oversees the entire production of each programme. In 2011, he was succeeded by Sietse Bakker.[39] In 2013, Vladislav Yakovlev took over the position of the EBU executive supervisor.[40] An announcement was made in December 2015, regarding the contract termination of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest Executive Supervisor Vladislav Yakovlev. Yakovlev was fired without any clear reasons after three contests, and was replaced by Jon Ola Sand who has been Executive Supervisor for the Eurovision Song Contest since 2011.[41] On 30 September 2019, Sand announced his intention to step down as Executive Supervisor and Head of Live Events after the Eurovision Song Contest 2020 in Rotterdam, Netherlands.[42]

Steering Group meetings tend to include the "Heads of Delegation" whose principal job is to liaise between the EBU and the broadcaster they represent. It is also their duty to make sure that the performers are never left alone without an adult and to "create a team atmosphere amongst the [performers] and to develop their experience and a sense of community."[2]

The list of executive supervisors of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest appointed by the EBU since the first edition (2003) is the following:

| Country | Name | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Svante Stockselius | 2003–2010 | |

| Sietse Bakker | 2011–2012 | |

| Vladislav Yakovlev | 2013–2015 | |

| Jon Ola Sand | 2016–2019 | |

| Martin Österdahl[43] | 2020– | |

Junior Eurovision logo and theme

.svg.png)

The former generic logo was introduced for the 2008 Junior Eurovision Song Contest in Cyprus,[44] to create a consistent visual identity. Each year of the contest, the host country creates a sub-theme which is usually accompanied and expressed with a sub-logo and slogan. The theme and slogan are announced by the EBU and the host country's national broadcaster.

The generic logo was revamped in March 2015,[45] seven years after the first generic logo was created. The logo was used for the first time in the 2015 Junior Eurovision Song Contest, the 13th edition of the contest.

Slogans

Since the 2005 contest, slogans have been introduced in the show. The slogan is decided by the host broadcaster and based on the slogan, the theme and the visual design are developed.

| Year | Host country | Host city | Slogan |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Hasselt | Let's Get Loud | |

| 2006 | Bucharest | Let the Music Play | |

| 2007 | Rotterdam | Make a Big Splash | |

| 2008 | Limassol | Fun in the Sun | |

| 2009 | Kiev | For the Joy of People | |

| 2010 | Minsk | Feel the Magic | |

| 2011 | Yerevan | Reach for the top! | |

| 2012 | Amsterdam | Break the Ice | |

| 2013 | Kiev | Be Creative | |

| 2014 | Marsa[46] | #Together | |

| 2015 | Sofia | #Discover | |

| 2016 | Valletta | Embrace | |

| 2017 | Tbilisi | Shine Bright | |

| 2018 | Minsk | #LightUp | |

| 2019 | Gliwice | Share the Joy |

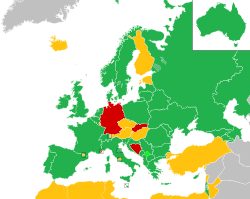

Participation

Only active member broadcasters of the EBU are permitted to take part and vote in the contest,[2] though the contest has been screened in several non-participating countries.[11][47]

Participation in the contest tends to change dramatically each year. The original Scandinavian broadcasters left the contest in 2006 because they found the treatment of the contestants unethical,[48] and revived the MGP Nordic competition, which had not been produced since the Junior Eurovision Song Contest began. Out of the thirty-nine countries that have participated at least once, two (Belarus and the Netherlands) have been represented by an act at every contest as of 2019.

39 countries have competed at least once. Listed are all the countries that have ever taken part in the competition alongside the year in which they made their debut:

|

|

|

- a) Before the Prespa agreement in 2018 presented as Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

- b) In 2006, the Federation of Serbia and Montenegro split into separate independent parts of Serbia and Montenegro, which debuted at the competition in 2006 and 2014, respectively.

- c) The participation of Australia was intended to be a one-off event to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Contest unless they won in 2015 in which case they would have been allowed to defend their crown in 2016. However it was revealed in May 2015 that Australia might become a permanent participant following some reports by Jon Ola Sand to the Swedish broadcaster.[49] In November 2015, the EBU announced that Australia would return in 2016 and after this the country would become an effective participant in the contest.

- d) Starting from the 2018 edition, the Kazakhstan broadcaster, which is an associate member, is invited to participate by the EBU and the contest organizer.

- e) Is part of the United Kingdom.

Winning entries

Overall, eleven countries have won the contest since the inaugural contest in 2003. Six have won the contest once: Armenia, Croatia, Italy, Spain, Ukraine, and the Netherlands. Four have won the contest twice: Belarus, Malta, Poland (first country to win back to back) and Russia; while Georgia has won three times. Both Croatia and Italy achieved their wins on their debut participation in the contest.

| Year | Date | Host city | Entries | Winner | Song | Performer | Points | Margin | Runner-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 15 Nov | 16 | "Ti si moja prva ljubav" | Dino Jelusić | 134 | 9 | |||

| 2004 | 20 Nov | 18 | "Antes muerta que sencilla" | María Isabel | 171 | 31 | |||

| 2005 | 26 Nov | 16 | "My vmeste" (Мы вместе) | Ksenia Sitnik | 149 | 3 | |||

| 2006 | 2 Dec | 15 | "Vesenniy Jazz" (Весенний джаз) | Tolmachevy Sisters | 154 | 25 | |||

| 2007 | 8 Dec | 17 | "S druz'yami" (С друзьями) | Alexey Zhigalkovich | 137 | 1 | |||

| 2008 | 22 Nov | 15 | "Bzz.." | Bzikebi | 154 | 19 | |||

| 2009 | 21 Nov | 13 | "Click Clack" | Ralf Mackenbach | 121 | 5 |

| ||

| 2010 | 20 Nov | 14 | "Mama" (Մամա) | Vladimir Arzumanyan | 120 | 1 | |||

| 2011 | 3 Dec | 13 | "Candy Music" | CANDY | 108 | 5 | |||

| 2012 | 1 Dec | 12 | "Nebo" (Небо) | Anastasiya Petryk | 138 | 35 | |||

| 2013 | 30 Nov | 12 | "The Start" | Gaia Cauchi | 130 | 9 | |||

| 2014 | 15 Nov | 16 | "Tu primo grande amore" | Vincenzo Cantiello | 159 | 12 | |||

| 2015 | 21 Nov | 17 | "Not My Soul" | Destiny Chukunyere | 185 | 9 | |||

| 2016 | 20 Nov | 17 | "Mzeo" (მზეო) | Mariam Mamadashvili | 239 | 7 | |||

| 2017 | 26 Nov | 16 | "Wings" | Polina Bogusevich | 188 | 3 | |||

| 2018 | 25 Nov | 20 | "Anyone I Want to Be" | Roksana Węgiel | 215 | 12 | |||

| 2019 | 24 Nov | 19 | "Superhero" | Viki Gabor | 278 | 51 | |||

| 2020 | TBD | TBD | |||||||

Interval acts and guest appearances

The tradition of interval acts between the songs in the competition programme and the announcement of the voting has been established since the inaugural contest in 2003. Interval entertainment has included such acts as girl group Sugababes and rock band Busted (2003),[65] Westlife in 2004, juggler Vladik Myagkostupov from the world-renowned Cirque du Soleil (2005)[66] and singer Katie Melua in 2007.[67] Former Eurovision Song Contest participants and winners have also performed as the interval act, such as Dima Bilan and Evridiki in 2008, Ani Lorak (2009), Alexander Rybak in 2010 and Sirusho (2011). Emmelie de Forest and the co-host that year, Zlata Ognevich, performed in 2013. 2015 host Poli Genova and Jedward were two of the interval acts in 2016.[68][69]

The winners of Junior Eurovision from 2003 to 2009 performed a medley of their entries together on stage during the 2010 interval.[70]

The previous winner has performed on a number of occasions since 2005, and from 2013 all participants have performed a "common song" together on stage during the interval. Similar performances took place in 2007 and 2010 with the specially-commisionned UNICEF songs "One World"[71] and "A Day Without War" respectively, the latter with Dmitry Koldun.[72] The official charity song for the 2012 contest was “We Can Be Heroes”, the money from the sales of which went to the Dutch children’s charity KidsRights Foundation.[73]

The 2008 event in Limassol, Cyprus finished with the presenters inviting everyone on stage to sing "Hand In Hand", which was written especially for UNICEF and the Junior Eurovision Song Contest that year.[74][75]

Ruslana was invited to perform at the 2013 contest which took place in her country's capital Kiev.[76] Nevertheless, on the day of the contest she withdrew her act from the show considering the violence shown by the Ukrainian authorities against those who were peacefully protesting in the country's capital.[77]

Since 2004 (with the exceptions of 2012, 2014 and 2017), the opening of the show has included a "Parade of Nations" or the "Flag Parade", similar to the Olympic Games opening ceremony. The parade was adopted by the Eurovision Song Contest in 2013 and has continued every year since.

Eurovision Song Contest

Below is a list of former-participants of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest who have gone on to participate at the senior version of the contest. Since 2014, the winner of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest has been invited as a guest to the final of the adult contest.[78]

| Country | Participant | JESC Year | ESC Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Weronika Bochat1 | 2004 | 2010 | Backing vocalist for Marcin Mroziński |

| Serbia | Nevena Božović | 2007 | 2013 | Competed as a part of Moje 3 with "Ljubav je svuda" which placed eleventh in the first semi-final. |

| 2019 | Competed with "Kruna" which placed eighteenth in the final | |||

| Russia | Tolmachevy Sisters | 2006 | 2014 | Competed with "Shine" which placed seventh in the final |

| San Marino | Michele Perniola | 2013 | 2015 | Competed as a duet performing "Chain of Lights" which placed sixteenth in the second semi-final |

| Anita Simoncini2 | 2014 | |||

| Armenia | Masha Mnjovan | 2008 | 2016 | Backing vocalist for Iveta Mukuchyan |

| Monica2 | 2008 | 2018 | Backing vocalist for Sevak Khanagyan | |

| Netherlands | O'G3NE3 | 2007 | 2017 | Competed with "Lights and Shadows" which placed eleventh in the final |

| Lithuania | Ieva Zasimauskaitė4 | 2007 | 2018 | Competed with "When We're Old" which placed twelfth in the final |

| Malta | Destiny Chukunyere | 2015 | 2019 | Backing vocalist for Michela |

| 2021 | Will represent Malta | |||

| Netherlands | Stefania Liberakakis5 | 2016 | 2021 | Will represent Greece |

See also

- Bala Turkvision Song Contest

- Eurovision Choir of the Year

- Eurovision Dance Contest

- Eurovision Magic Circus Show

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Eurovision Young Dancers

- Eurovision Young Musicians

- MGP Nordic

Notes

- ^ Kosovo has never participated in the contest. However, in the competition period 2005–2007, Kosovo was a province of Serbia, which itself was a constituent republic of participating country Serbia and Montenegro at the time of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2005.

References

- "Official information page" (in French). European Broadcasting Union. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Extract of rules of the 2006 contest" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "Generic contest information page". European Broadcasting Union. December 2007. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "The new Junior Eurovision Song Contest in high definition". European Broadcasting Union. November 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Junior Eurovision live on the internet". ESC Today. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "IMDB: Børne1'erens melodi grand prix 2000". IMDb. 1 May 2000. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "IMDB: de unges melodi grand prix 2001". IMDb. 1 May 2001. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "IMDB: MGP Nordic 2002". IMDb. 1 December 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "MGP Nordic 2002". esconnet.dk (in Danish). 27 April 2002. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "First EBU press release on JESC 2003". European Broadcasting Union. 22 November 2002. Archived from the original on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Confirmation of Manchester as original host". European Broadcasting Union. 16 November 2003. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "'Junior contest not to take place in Manchester'". ESC Today. 13 May 2004. Archived from the original on 17 November 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Cozens, Claire (17 November 2003). "JESC UK ratings". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "'Junior 2004 in Croatia'". ESC Today. 1 June 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "'Junior contest moves to Norway'". ESC Today. 17 June 2004. Archived from the original on 16 November 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "'Junior 2005 on 26 November in Belgium'". ESC Today. 20 November 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "'No DVD from JESC 2007'". Oikotimes. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Official information on the 2005 contest". European Broadcasting Union. 24 November 2005. Archived from the original on 3 August 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- "'Televoting all night long'". ESC Today. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- Siim, Jarmo (15 July 2011). "12 countries for Junior Eurovision 2011, several changes coming up". European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Belinkomsten finale Junior Eurovisie Songfestival naar Unicef" (in Dutch). UNICEF. 6 December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Information on the fine/ban rule implemented on Croatia and the scrapping of the live rule". ESC Today. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- Harvey, Dennis (17 September 2008). "Variety review of Sounds Like Teen Spirit". Variety. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Premiere of JESC film in Cyprus". IMDb. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Video of Belgian premiere of JESC Film". YouTube. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- "Premiere of JESC film in Cyprus". CyBC. September 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- "Junior: Minor format changes introduced". European Broadcasting Union. 6 June 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "'Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2008'". European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "NTU reveals all with under 50 days to go". European Broadcasting Union. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Farren, Neil (15 October 2017). "Minsk to Host Junior Eurovision 2018". eurovoix.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "'Third Junior Eurovision Song Contest': Information on the 2005 running order draw". European Broadcasting Union. 14 October 2005. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "'JESC official presentation tomorrow'". ESC Today. 21 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "'Exclusive: The singing logo is the co-host!!!'". ESC Today. 6 November 2006. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Fisher, Luke James (10 September 2014). "Moira Delia to host Junior Eurovision 2014". JuniorEurovision.tv. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Fisher, Luke James (21 October 2015). "Meet your host... Poli Genova!". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "'Your votes please: the spokespersons'". ESC Today. 26 November 2005. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Rules alterations for 2010 contest as well as details of traditional rules". ESCKaz. 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Rules of the 2003 contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 6 December 2003. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- "Information on the Steering Group". Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation. 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- Jarmo, Siim. "Junior 2013 venue confirmed". JuniorEurovision.tv. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Van Gorkum, Steef (2 December 2015). "EBU fires Executive Supervisor Yakovlev". escdaily.com. ESC Daily. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Jon Ola Sand to step down as Executive Supervisor after Rotterdam 2020". Eurovision.tv. 30 September 2019.

- Farren, Neil (20 January 2020). "Martin Österdahl Appointed Eurovision Executive Supervisor". eurovoix.com.

- "'New logo for the Junior Eurovision Song Contest'". European Broadcasting Union. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Photo gallery: Junior Eurovision 2015 Logo - Junior Eurovision Song Contest — Tbilisi 2017". junioreurovision.tv. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Fisher, Luke James (18 December 2013). "Malta to host Junior Eurovision 2014". JuniorEurovision.tv. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "'Israel getting into the JESC spirit'". ESC Today. 22 November 2007. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- "News – Scandinavian JESC pull-out". ESC Today. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Waddell, Nathan (21 May 2015). "Australia: Australia may become a solid participant, says JOS". escXtra. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "Results of the 2003 contest". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Results of the 2004 contest". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Results of the 2005 contest". Oikotimes. 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Results of the 2006 contest". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Results of the 2007 contest". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "'Exclusive: 13 countries to be represented at Junior 2009!'". European Broadcasting Union. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "'Exclusive: Belarus to host Junior 2010'". European Broadcasting Union. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- Siim, Jarmo (18 January 2011). "Armenia to host Junior Eurovision in 2011". European Broadcasting Union.

- "Junior 2012 in Amsterdam on December 1". European Broadcasting Union. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Siim, Jarmo (7 February 2013). "Ukraine to host Junior 2013". EBU.

- "Junior Eurovision 2015: 21 November in Sofia, Bulgaria". JuniorEurovision.tv. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Malta to host the 14th Junior Eurovision Song Contest!". eurovision.tv. eurovision. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Granger, Anthony (26 February 2017). "Tbilisi to Host the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2017". eurovoix.com. Eurovoix.

- Jordan, Paul (15 October 2017). "Minsk announced as the host city for Junior Eurovision 2018!". junioreurovision.tv. EBU.

- "Gliwice-Silesia Host City of Junior Eurovision 2019". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 6 March 2019.

- "Remember the first ever Junior Eurovision Song Contest?". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 9 November 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Remember the 2005 Junior Eurovision Song Contest?". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Katie Melua star act Junior Eurovision Song Contest". eurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Jordan, Paul (3 November 2016). "Destiny and Poli Genova join Junior Eurovision 2016!". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "JESC'16: Jedward To Perform "Hologram" in Sunday's Final". Eurovoix. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Eurovision Song Contest Minsk 2010". junioreurovision.tv. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Belarusian delegation to leave for Junior Eurovision 2007 in Rotterdam". www.tvr.by. 29 November 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Exclusive: Koldun's song for UNICEF". junioreurovision.tv. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "JESC'12: The Official Charity Song". Eurovoix. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Our stars sing to help others!". junioreurovision.tv. 22 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Photo gallery: UNICEF song rehearsal". junioreurovision.tv. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Remarkable Ruslana to perform with a children's choir at the Junior Eurovision Song Contest". junioreurovision.tv. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Why wasn't Ruslana at Junior Eurovision?". web.archive.org. ESC Reporter. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- The 2018 winner, Poland's Roksana Węgiel, was guested during the first semifinal of the following year's Eurovision

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Junior Eurovision Song Contest. |