Hunky Dory

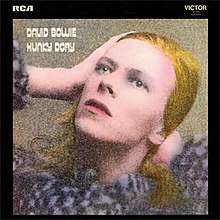

Hunky Dory is the fourth studio album by English singer-songwriter David Bowie, released on 17 November 1971 in the UK and 4 December 1971 in the US by RCA Records. It was his first release through RCA, which would be his label for the next decade. Following the hard rock sound of The Man Who Sold the World, Hunky Dory marked a move towards art rock and art pop styles. Co-produced by Ken Scott and Bowie himself, it was recorded in mid-1971 at Trident Studios in London and featured Rick Wakeman on piano and the musicians who would later be known as the Spiders from Mars – comprising Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey. The album cover, photographed by Brian Ward in monochrome and re-coloured by Terry Pastor, was influenced by a Marlene Dietrich photo book that Bowie took with him to the photoshoot.

| Hunky Dory | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

CD and UK album cover (The original US album cover bears no title) | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 17 November 1971 (UK) 4 December 1971 (US) | |||

| Recorded | 8 June – 6 August 1971 | |||

| Studio | Trident, London | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 41:50 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Hunky Dory | ||||

| ||||

The album was initially released to favourable critical and commercial reception but wasn't a major success until the commercial breakthrough of his following album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972). It was supported by the singles "Changes" in 1972 and "Life on Mars?" in 1973. Retrospectively, Hunky Dory has received critical acclaim and is regarded as one of Bowie's best works. Time chose it as part of their "100 best albums of all time" list in January 2010, with journalist Josh Tyrangiel praising Bowie's "earthbound ambition to be a boho poet with prodigal style".[1] The album has been reissued multiple times and remastered in 2015 as part of the Five Years (1969–1973) box set.

Background

Following the completion of his third studio album The Man Who Sold the World in May 1970, Bowie became less active in both the studio and on stage. This was partly due to challenges that were confronting his new manager Tony Defries, who Bowie hired after firing his old manager Kenneth Pitt and departing music publisher Essex Music.[2][3] After hearing Bowie's new single "Holy Holy", Defries signed a contract with Chrysalis but thereafter limited his work with Bowie to focus on other projects, including attempting to sign American singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder following his contract ending with Motown Records. Because of this, Bowie, who was devoting himself to songwriting, turned to Chrysalis partner Bob Grace. Grace, according to biographer Nicholas Pegg, had "courted" Bowie on "the strength of 'Holy Holy'", and subsequently booked time at Radio Luxembourg's studios in London for Bowie to record his demos.[2][3] In August 1970, due to his disillusionment with Bowie's lack of enthusiasm during the sessions for The Man Who Sold the World and his dislike of Defries, bassist and producer Tony Visconti parted ways with Bowie; it was the last time he would see the artist for three to four years.[4][5] Mick Ronson and Woody Woodmansey, who played guitar and drums, respectively for The Man Who Sold the World, similarly parted ways with Bowie, primarily due to their disgruntlement with the artist on top of not being paid for their performances.[4] Visconti would then produce music for glam rock artist Marc Bolan while Ronson and Woodmansey went to Haddon Hall in Bakewell, Derbyshire and formed a short-lived group called Ronno with Benny Marshall of the Rats.[5][6]

According to his then-wife Angela, Bowie had spent time at Haddon composing songs on piano rather than acoustic guitar, which would "infuse the flavour of the new album."[3] Biographer Marc Spitz notes that a piano could not fit in his Plaistow Grove bedroom, nor was it suitable for playing in clubs or bus tours with his previous groups. Haddon Hall, however, gave him more of a sense of comfort and permanence, something he had not felt before when composing.[7] Here he composed over three dozen songs, many of which would end up on Hunky Dory and its follow-up The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.[8] Two of these were "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself", which he recorded with his short-lived band Arnold Corns in February 1971,[9] and subsequently re-recorded for Ziggy Stardust.[8][10] The first song Bowie wrote and demoed for Hunky Dory was "Oh! You Pretty Things" in January 1971. After recording a demo at Radio Luxembourg, Bowie gave the tape to Grace, who showed it to Peter Noone of Herman's Hermits. Noone decided to record "Oh! You Pretty Things" and released it as his debut single later that year.[10][11] Noone's version reached number 12 on the UK Singles Chart in mid-June, with Noone telling NME: "My view is that David Bowie is the best writer in Britain at the moment...certainly the best since Lennon and McCartney."[12]

Writing and recording

After the minimal critical and commercial impact of his Arnold Corns project and leaving Mercury Records, Bowie regrouped in the studio in May 1971 to begin work on his next album.[13][14] Initially, he was joined by Arnold Corns guitarist Mark Pritchett, Space Oddity drummer Terry Cox and his former Turquoise colleague Tony Hill. However, he came to the conclusion that he couldn't do the project without Ronson.[13] Ronson, who had not talked to Bowie in nine months and had become depressed, was enthusiastic when Bowie contacted him. Woodmansey returned with Ronson, who recruited a new bass player to replace Visconti. He initially suggested Rick Kemp, who Bowie recorded with in the King Bees in the mid-1960s. However, upon meeting Bowie at Haddon Hall to audition, Bowie was dismissive of him and, according to Pegg, some reports say that Defries rejected Kemp on the grounds of his "receding hairline;" Kemp would instead join the English folk rock band Steeleye Span.[13] So, Ronson suggested his acquaintance Trevor Bolder, a former hairdresser and piano tuner who had previously seen Bowie live in 1970 and met Ronson at Haddon Hall.[13][15] Upon Bolder's hiring, the trio grouped at Haddon to rehearse some of Bowie's new material, of which included album track "Andy Warhol".[13]

Following the birth of his son Duncan, Bowie wrote the song "Kooks" as a tribute to him. Also known as 'Zowie', Bowie would tell David Wigg in 1973: "I got the name [Zowie] from a Batman comic."[15] On 3 June, Bowie and the Spiders, along with traveled to the BBC's Paris Studios in London to record for John Peel's radio show In Concert. They were joined by Dana Gillespie, Mark Pritchett, Geoffrey MacCormack (better known as Warren Peace) and George Underwood.[16][17] The songs they performed were all originals written by Bowie, apart from a cover of Chuck Berry's "Almost Grown" and Ron Davies' "It Ain't Easy",[16] which was to be recorded for Ziggy Stardust a year later.[17] The performance began with "Queen Bitch" and "Bombers", which Peel says will both be on the upcoming album, although "Bombers" was to replaced by the cover "Fill Your Heart".[18] They also played "The Supermen" from The Man Who Sold the World, "Looking for a Friend" (which was sung by Pritchett), "Song for Bob Dylan" (which was sung by Underwood) and "Andy Warhol" (which was sung by Gillespie).[16][17] Although Bowie's backing trio were referred to as "members of a group called Ronno", the session would become the first performance with the trio who would become known as the Spiders from Mars and who would record with him for the next three years.[15][17][19]

– Mick Ronson, 1983

Bowie and the Spiders officially started work on the album at Trident Studios in London on 8 June 1971.[16] In Visconti's place as a producer was Ken Scott, who would produce Bowie's next three albums: Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and Pin Ups.[19][20] Scott's first album as a producer,[21] he was previously an engineer on Bowie's two previous albums, along with the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour (1967) and the "White Album" (1968) at Abbey Road Studios and George Harrison's All Things Must Pass (1970), which featured an acoustic sound that Scott borrowed for Hunky Dory.[21][22] Bowie played multiple demos for Scott and the two would then select which ones would be recorded for the album.[23] On 8 June, the band recorded "Song for Bob Dylan",[16] although according to Pegg this version was scrapped and the real version wasn't recorded until 23 June.[13] Recording was done very quickly, with Scott recalling in 1999: "Almost everything was done in one take."[16] Scott recalled that both himself and the Spiders would think a certain section needs to be rerecorded, whether it be vocals or guitar, but Bowie would say "No, wait, listen", and when all parts were played simultaneously that would sound perfect, much to Scott's astonishment.[23] Bolder described recording with Bowie for the first time as a "nerve-wracking experience", saying in 1993: "When that red light came on in the studio it was, God, in at the deep end of what!"[16] Bowie had a much better attitude during the sessions, taking an active role in the album's sound and arrangements, a stark contrast to The Man Who Sold the World, which he was generally dismissive of.[4][21]

Keyboardist Rick Wakeman, then of the Strawbs and a noted session musician,[21] plays piano on the album.[24] Wakeman was asked to play during the album's sessions and accepted. He recalled in 1995 that he met Bowie in late June 1971 at Haddon Hall, where Bowie played him demos of "Changes" and "Life on Mars?" in "their raw brilliance". He recalled: "He [played] the finest selection of songs I have ever heard in one sitting in my entire life...I couldn't wait to get into the studio and record them."[25] The piano Wakeman played on the album was an 1898 Bechstein that was the same one used for the Beatles' 1968 song "Hey Jude" and many of Elton John and Harry Nilsson's early records, and would later be used by Queen for "Bohemian Rhapsody".[26] According to Wakeman, the sessions initially had a rough start, due to the band not learning the songs. He recalled in the Radio 2 documentary Golden Years and his autobiography Say Yes! that Bowie had to halt the sessions, telling the musicians off and to come back when they knew the music. Upon returning after a week, Wakeman said: "the band were hot! They were so good, and the tracks just flowed through."[26] However, this account has been disputed by other band members, including Bolder, who told Cann: "[That's] rubbish. David would never have told the band off in the studio. Especially as Mick and Woody had already left him once, and everyone was now getting on. The band would not have survived that – it definitely didn't happen."[25][26] Similarly, Scott said: "I definitely don't remember that, and it's not something I would forget. I would definitely dispute that one."[25][26]

With Wakeman on the line-up, Bowie and the Spiders recorded reconvened at Trident on 9 July and recorded two takes of "Bombers" and "It Ain't Easy", the latter featuring backing vocals by Dana Gillespie.[25] According to Cann, five days later on 14 July, Defries sent a letter to jazz pianist Dudley Moore asking him to play piano during a session. There is no known record of Moore responding and although the specific song Defries was asking him to play on is unknown, Cann deduces that it was most likely "Life on Mars?".[25][21] During this day, the group recorded four takes of "Quicksand", the final take appeared on the finished album.[27] On 18 July, the group spent the day rehearsing and mixing. During the session, Bowie was introduced by Grace to a band known as Chameleon. He gave them his future Ziggy Stardust track "Star", which they recorded their own unreleased version of.[28] On 26 July, a seven-hour mixing session took place in order to compile a promotional album for Gem Productions. At this point, the songs "Oh! You Pretty Things", "Eight Line Poem", "Kooks", "Queen Bitch" and "Andy Warhol" were recorded, although the mixes of "Eight Line Poem" and "Kooks" on the promotional album were different than the final mixes on Hunky Dory.[29] Two takes of "The Bewlay Brothers" were recorded on 30 July, the second take appearing on the final album. It was recorded on a tape that contained rejected versions of "Song for Bob Dylan" and "Fill Your Heart".[30] On 6 August, the band recorded "Life on Mars?" and "Song for Bob Dylan", after which the album recording is deemed complete. Ronson guided the recording of "Life on Mars?", counting in each take and overdubbed his guitar, strings, Mellotron and Bowie's vocal.[30] Cann does not have a recording date for "Changes",[31] but Doggett writes that it was recorded sometime between June and July.[32]

Music and lyrics

Author Peter Doggett describes Hunky Dory as "a collective of attractively accessible pop songs, through which Bowie tested out his feelings about the nature of stardom and power."[33] Musical biographer David Buckley said of the album: "Its almost easy-listening status and conventional musical sensibility has detracted from the fact that, lyrically, this record lays down the blueprint for Bowie's future career."[34] Spitz describes it as a piano-driven record and because of this, it offers more of an inviting and warmer feel, especially when compared to Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World.[7] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic describes the album as "a kaleidoscopic array of pop styles, tied together only by Bowie's sense of vision: a sweeping, cinematic mélange of high and low art, ambiguous sexuality, kitsch, and class."[35] The opening track, "Changes", focused on the compulsive nature of artistic reinvention ("Strange fascination, fascinating me/Changes are taking the pace I'm going through") and distancing oneself from the rock mainstream ("Look out, you rock 'n' rollers"). However, the composer also took time to pay tribute to his influences with the tracks "Song for Bob Dylan", "Andy Warhol" and the Velvet Underground inspired "Queen Bitch".

Following the hard rock of Bowie's previous album The Man Who Sold the World, Hunky Dory saw the partial return of the fey pop singer of Space Oddity, with light fare such as "Kooks" and the cover "Fill Your Heart" sitting alongside heavier material like the occult-tinged "Quicksand" (whose lyric mentions the Golden Dawn (i.e. the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn) and Aleister Crowley) and the semi-autobiographical "The Bewlay Brothers". Between the two extremes was "Oh! You Pretty Things", whose pop tune hid lyrics, inspired by Nietzsche, predicting the imminent replacement of modern man by "the Homo Superior", and which has been cited as a direct precursor to "Starman" from Bowie's next album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.[36]

Title and artwork

Although Bowie generally left naming his albums until last minute, the title, 'Hunky Dory', was announced at the John Peel session.[13] It was suggested by Bob Grace of Chrysalis, who got the idea from an Esher pub landlord and formerly of the Royal Air Force. He told Peter and Leni Gillman, the authors of Alias David Bowie, that the landlord had an unusual vocabulary that was "peppered with upper-crust jargon", using words such as 'prang' and 'whizzo', and phrases such as 'everything's hunky-dory'. Grace told Bowie and he loved it.[37] Pegg notes that there was a song from 1957 by the American doo-wop band the Guytones also titled "Hunky Dory" that may have played a part as well.[21] Spitz notes that 'hunky-dory' is an English slang term that means everything is right in the world.[8] The album's sleeve would bear the credit "Produced by Ken Scott (assisted by the actor)". The "actor" was Bowie himself, whose "pet conceit", in the words of NME critics Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray, was "to think of himself as an actor".[38]

The cover artwork was taken by photographer Brian Ward at his Heddon Street studio,[39] who was introduced to Bowie by Grace. One idea was for Bowie to dress as an Egyptian Pharoah, partly inspired by the British media's infatuation with the British Museum's new Tutankhamun exhibit.[40] Photos of Bowie posing as a sphinx and in a lotus position were taken – one of them was released as part of the 1990 Space Oddity reissue – but the idea was ultimately not chosen. Bowie later recalled: "We didn't run with it, as they say. Probably a good idea."[40] Rather than something extravagant, Bowie opted for a more minimalist image reflecting the album's "preoccupation with the silver screen." Bowie later said: "I was into Oxford bags, and there are a pair, indeed, on the back of the album. [I was attempting] what I presumed was kind of an Evelyn Waugh Oxbridge look."[41] The final image is a close-up of Bowie looking up into space as he pushes his hair back from his forehead. Originally shot in monochrome, the image was re-coloured by illustrator Terry Pastor, who recently set up the Main Artery design studio in Covent Garden with George Underwood; Pastor would later design the cover and sleeve for Ziggy Stardust.[41] Pegg writes: "Bowie's decision to use a re-coloured photo suggests a hand-tinted lobby-card from the days of the silent cinema and, simultaneously, Warhol's famous Marilyn Diptych screen-prints."[41] Robert Dimery, in his book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, writes that Bowie took a photo book that contained multiple Dietrich prints with him to the photoshoot.[42]

Release and aftermath

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[46] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 9/10[50] |

| The Village Voice | A−[51] |

Following the success of Peter Noone's version of "Oh! You Pretty Things", Defries sought to extricate Bowie from his contract with Mercury Records, the label that distributed Bowie's previous two albums.[2][3] Although his contract was to expire in June 1971, Mercury had intended to renew it with improved terms. However, Defries succeeded in forcing Mercury to terminate his contract in May after threatening to deliver a low-quality album.[52] Defries was then able to pay off Bowie's debts to Mercury through Gem Productions; Mercury then surrendered their copyright on David Bowie (1969) and The Man Who Sold the World (1970).[13] After ending the contract with Mercury, Defries presented the album to multiple labels in the US. RCA Records, stationed in New York City, liked the album and signed Bowie to a three-album deal on 9 September 1971; RCA would be Bowie's label for the rest of the 1970s.[53]

Hunky Dory was released on 17 November 1971 in the UK and 4 December 1971 in the US by RCA Records.[41][54] Supported by the single "Changes", the album scored generally favourable reviews and sold reasonably well on its initial release, without being a major success.[38] Melody Maker called it "the most inventive piece of song-writing to have appeared on record in a considerable time", while NME described it as Bowie "at his brilliant best".[41] In the United States, Rolling Stone opined that "Hunky Dory not only represents Bowie's most engaging album musically, but also finds him once more writing literally enough to let the listener examine his ideas comfortably, without having to withstand a barrage of seemingly impregnable verbiage before getting at an idea".[55] However, it was only after the commercial breakthrough of Ziggy Stardust in mid-1972 that Hunky Dory became a hit, climbing to number 3 in the UK[56] and remaining on the chart for 69 weeks.[57] In 1973, RCA released "Life on Mars?" as a single, which also made number 3 in the UK.[58] A reissue returned the album, in January 1981, to the British chart, where it remained for 51 weeks.[57]

Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic praised the album writing, "On the surface, [having] such a wide range of styles and sounds would make an album incoherent, but Bowie's improved songwriting and determined sense of style instead made Hunky Dory a touchstone for reinterpreting pop's traditions into fresh, postmodern pop music."[35] In 1998, Q magazine readers voted Hunky Dory the 43rd greatest album of all time, while in 2000 the same magazine placed it at number 16 in its list of the 100 Greatest British Albums Ever. It was also voted number 23 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums 3rd Edition (2000). In 2003, the album was ranked 107th on Rolling Stone's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and 108 in a 2012 revised list.[59] In the same year, VH1 placed it 47th and the Virgin All Time Top 1000 Albums chart placed it at number 16. In 2004, it was ranked 80th on Pitchfork's Top 100 Albums of the 1970s. In 2006, TIME magazine chose it as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[1] According to Acclaimed Music, it is the 70th most celebrated album in popular music history.[60]

Bowie himself considered the album to be one of the most important in his career. Speaking in 1999, he said: "Hunky Dory gave me a fabulous groundswell. I guess it provided me, for the first time in my life, with an actual audience – I mean, people actually coming up to me and saying, 'Good album, good songs.' That hadn't happened to me before. It was like, 'Ah, I'm getting it, I'm finding my feet. I'm starting to communicate what I want to do. Now: what is it I want to do?' There was always a double whammy there."[61] Spitz writes that many artists have their "it all came together on this one" record, naming the likes of Beggars Banquet by the Rolling Stones, Damn the Torpedoes by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, War by U2 and The Bends by Radiohead. "For David Bowie, it's Hunky Dory."[62]

Track listing

All tracks written by David Bowie, except where noted.[63]

- Side one

- "Changes" – 3:37

- "Oh! You Pretty Things" – 3:12

- "Eight Line Poem" – 2:55

- "Life on Mars?" – 3:43

- "Kooks" – 2:53

- "Quicksand" – 5:08

- Side two

- "Fill Your Heart" (Biff Rose, Paul Williams) – 3:07

- "Andy Warhol" – 3:56

- "Song for Bob Dylan" – 4:12

- "Queen Bitch" – 3:18

- "The Bewlay Brothers" – 5:22

- Sides one and two were combined as tracks 1–11 on CD reissues.

CD releases

1980s and 1990s

Following its initial release on compact disc in the mid-1980s, Hunky Dory was re-released in CD format in 1990, by Rykodisc/EMI, with bonus tracks.[64]

- Bonus tracks (1990 Rykodisc)

- "Bombers" (Previously unreleased track, recorded in 1971, mixed 1990; there is a very rare LP sampler issued by RCA prior to the release of the album with the GEM logo on the cover and "Bombers" appears followed by the linking cross talk that leads into "Andy Warhol," clearly indicating that Bowie had originally intended it to be the opening track on the second side [instead of "Fill Your Heart"]) – 2:38

- "The Supermen" (Alternate version recorded on 12 November 1971 during sessions for The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, originally released on Revelations – A Musical Anthology for Glastonbury Fayre in July 1972, compiled by the organisers of the Glastonbury Festival at which Bowie had played in 1971[65]) – 2:41

- "Quicksand" (Demo version, recorded in 1971, mixed 1990) – 4:43

- "The Bewlay Brothers" (Alternate mix) – 5:19

In 1999, the album was reissued by Virgin/EMI (7243 521899 0 8), without bonus tracks, but with 24-bit digitally remastered sound. This edition was re-pressed in 2014 by Parlophone/Warner Music Group, having acquired the Virgin-owned Bowie catalogue.

Personnel

Album credits per Nicholas Pegg.[3]

- David Bowie – vocals, guitar, alto and tenor saxophone, piano (in "Oh! You Pretty Things" (together with Rick Wakeman[69][70]), "Eight Line Poem" and "The Bewlay Brothers")

- Mick Ronson – guitar, vocals, Mellotron, arrangements

- Trevor Bolder – bass guitar, trumpet

- Mick Woodmansey – drums

- Rick Wakeman – piano

Production

- Ken Scott – producer, recording engineer, mixing engineer

- David Bowie – producer

- Dr. Toby Mountain – remastering engineer (for Rykodisc release)

- Jonathan Wyner – assistant remastering engineer, mixing engineer (for Rykodisc release)

- Peter Mew – remastering engineer (for EMI release)

- Nigel Reeve – assistant remastering engineer (for EMI release)

- George Underwood – cover art

Charts

Album

| Year | Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | UK Albums Chart[71] | 3 |

| 1972 | Norwegian Albums Chart | 33 |

| 1972 | Australian Albums Chart | 39 |

| 2016 | New Zealand Albums Chart[72] | 30 |

| 2016 | US Billboard 200[73] | 57 |

| 2016 | US Top Catalog Albums (Billboard)[74] | 4 |

Single

| Year | Single | Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | "Changes" | Billboard Hot 100[75] | 66 |

| 1973 | "Life on Mars?" | UK Singles Chart[71] | 3 |

| 1975 | "Changes" | Billboard Pop Singles[75] | 41 |

Certifications

| Organization | Level | Date |

|---|---|---|

| BPI – UK | Gold | 25 January 1982[76] |

| BPI – UK | Platinum | 25 January 1982[76] |

References

- Josh Tyrangiel; Alan Light (26 January 2010). "The All-TIME 100 Albums". TIME. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- Cann 2010, pp. 195–196.

- Pegg 2016, p. 603.

- Cann 2010, p. 197.

- Pegg 2016, p. 601.

- Cann 2010, p. 214.

- Spitz 2009, p. 159.

- Spitz 2009, p. 156.

- Cann 2010, pp. 206–207.

- Pegg 2016, p. 604.

- Cann 2010, pp. 202–203.

- Cann 2010, p. 220.

- Pegg 2016, p. 606.

- Cann 2010, pp. 216, 218.

- Cann 2010, p. 218.

- Cann 2010, p. 219.

- Pegg 2016, p. 1,093.

- Pegg 2016, p. 160.

- Gallucci, Michael (17 December 2016). "Revisiting David Bowie's First Masterpiece 'Hunky Dory'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Cann 2010, p. 234.

- Pegg 2016, p. 607.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 93–94.

- Buckley 2005, p. 94.

- Buckley 2005, p. 93.

- Cann 2010, p. 223.

- Pegg 2016, p. 608.

- Cann 2010, pp. 223–224.

- Cann 2010, p. 224.

- Cann 2010, pp. 224–225.

- Cann 2010, p. 225.

- Cann 2010, pp. 219–225.

- Doggett 2012, p. 140.

- Doggett 2012, p. 11.

- Buckley, David (2000) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. p. 112. ISBN 0-7535-0457-X.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Hunky Dory – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2004.

- Carr & Murray 1981, p. 44.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 606–607.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 7–11.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 610–611.

- Pegg 2016, p. 610.

- Pegg 2016, p. 611.

- Dimery, Robert (2005). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. London: Quintet Publishing. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-84403-392-8.

- "David Bowie: Hunky Dory". Blender (47). May 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled on Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "David Bowie". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-85712-595-8.

- Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Sheffield, Rob (18 March 1999). "David Bowie: Hunky Dory (reissue)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 October 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Dolan, Jon (July 2006). "How to Buy: David Bowie". Spin. 22 (7): 84. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Weisbard & Marks 1995, p. 55.

- Christgau, Robert (30 December 1971). "Consumer Guide (22)". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 605–606.

- Cann 2010, pp. 195, 227.

- Cann 2010, p. 231.

- Mendelsohn, John. "Hunky Dory". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Sheppard, David (February 2007). "60 Years of Bowie". MOJO Classic: 24.

-

- Roberts, David (editor). The Guinness Book of British Hit Albums, p71. Guinness Publishing Ltd. 7th edition (1996). ISBN 0-85112-619-7

- Buckley, David (2000) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. p. 624. ISBN 0-7535-0457-X.

- "500 Greatest Albums: Hunky Dory – David Bowie". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Hunky Dory ranked 70th most celebrated album". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Chris Roberts interview with David Bowie in Uncut, October 1999, Issue 29.

- Spitz 2009, p. 158.

- Hunky Dory (liner notes). David Bowie. UK: RCA Records. 1971. SF 8244.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Hunky Dory (liner notes). David Bowie. UK: EMI/Rykodisc. 1990. EMC 3572.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "EMI 30th Anniversary 2CD Limited Edition (2002)". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- Five Years (1969–1973) (Box set liner notes). David Bowie. UK, Europe & US: Parlophone. 2015. DBXL 1.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "FIVE YEARS 1969 – 1973 box set due September". davidbowie.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "David Bowie / 'Five Years' vinyl available separately next month". superdeluxeedition.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "Rick Wakeman reveals he played piano on David Bowie's "Oh! You Pretty Things" - Uncut". uncut.co.uk. 17 January 2017. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Bowie or Wakeman piano mystery". 17 May 2018. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "UK Top 40 Hit Database". Archived from the original on 19 March 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "The Official New Zealand Music Chart". Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "(Hunky Dory > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums)". AllMusic. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "David Bowie Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "(Hunky Dory > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles)". Allmusic. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "BPI Certified Awards". Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Sources

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. Eel Pie Pub. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (7th ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)