Hammer-headed bat

The hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus), also known as hammer-headed fruit bat and big-lipped bat, is a megabat widely distributed in equatorial Africa. This large bat is found in riverine forests, mangroves, swamps, and palm forests at elevations less than 1,800 metres (5,900 ft).

| Hammer-headed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Genus: | Hypsignathus H. Allen, 1861 |

| Species: | H. monstrosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Hypsignathus monstrosus H. Allen, 1861 | |

| |

| Hammer-headed bat range | |

Taxonomy and etymology

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position of Hypsignathus within Pteropodidae[2] |

The hammer-headed bat was described as a new species in 1861 by American scientist Harrison Allen. Allen placed the species into a newly-created genus, Hypsignathus.[3] The holotype had been collected by French-American zoologist Paul Du Chaillu[3] in Gabon.[4] The genus name Hypsignathus comes from Ancient Greek "húpsos" meaning "high" and "gnáthos" meaning "jaw." T. S. Palmer speculated that Allen chose the name Hypsignathus to allude to the "deeply arched mouth" of the species.[5] The species name "monstrosus" is Latin for "having the qualities of a monster."[6]

Initially, Allen identified the hammer-headed bat as a member of the subfamily Pteropodinae of the megabats.[3] However, in 1997, it was more recently recognized as a member of the subfamily Epomophorinae.[7] A 2011 study found that Hypsignathus was the most basal member of a clade of megabats that also included the following genera: Epomops, Micropteropus, Epomophorus, and Nanonycteris.[2] Together, these genera form the tribe Epomophorini within Epomophorinae.[7] Some taxonomists do not recognize Epomophorinae as a valid subfamily, though, and include its taxa within Rousettinae. In this alternate taxonomy, however, it is still placed within the tribe Epomophorini with the same other four genera.[8][9]

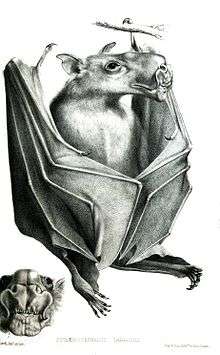

Physical description

The hammer-headed bat is the largest bat in Africa, with a wingspan of 68.6 to 97 cm (27.0 to 38.2 in) and a total length of 195 to 285 mm (7.7 to 11.2 in). Males, ranging from 228 to 450 g (8.0 to 15.9 oz), are significantly larger than females, which range from 218 to 377 g (7.7 to 13.3 oz).[10][11]

Pelage is grey-brown to slaty-brown with a whitish collar of fur extending from shoulder to shoulder.[12] The flight membranes are brown and the ears are dark brown with a tuft of white fur at the base. The face is dark brown with a few long, stiff whiskers around the mouth.

The skull may be diagnosed by specific dental features. The second premolar and molars are markedly lobed. This feature is specific for this genus, and no other African fruit bats have this characteristic.

There is extreme sexual dimorphism in this species.[13] The male possesses an enormous head for producing loud honking calls.[13] The enlarged rostrum, larynx and lips allow these sounds to be extremely resonant. The larynx is one half the length of the vertebral column and fills out most of the thoracic cavity. It is nearly three times larger in males than females. The male also has a hairless split chin and warty rostrum with wrinkled skin around it. Females have a much more fox-like appearance, similar to most fruit bats.[12]

Ecology and behavior

Hammer-headed bats are frugivores. Figs make up much of their diet, but they may also include mangos, bananas and guavas. There are some complications inherent in a fruit diet such as insufficient protein intake. It is suggested that fruit bats compensate for this by possessing a proportionally longer intestine compared to insectivorous species.[12] This enhances their ability to absorb protein. They do also have very rapid digestive systems allowing these bats to assimilate high amounts of fruit to ensure that adequate protein is absorbed. It is also suggested that by eating a wide variety of fruits with varying protein contents, fruit bats are able to maintain an entirely frugivorous diet.[14] In 1968, however, it was claimed that Hypsignathus killed and ate tethered chickens.[15]

Generally fruit is picked and taken to a nearby tree where it is chewed, the juice squeezed out and the pulp discarded. Since they often do not consume the pulp, these bats are not considered to be good seed distributors.[16] Males may forage long distances (up to 10 km or 6 mi) to locate the highest quality food. Females rely on established feeding routes that offer a constant supply of lower quality food. This may reflect different metabolic requirements based on body size differences.

Large bats often experience difficulties with overheating during flight. The limited thermoregulatory capabilities of flying bats appears to be one factor closely associated with why flight activity primarily occurs during cooler nocturnal temperatures. It has been found that hammer-headed bats are able to tolerate higher ambient temperatures during flight than other bats.[17] This ability is associated with this bat's high thermal conductance (Cf) which is defined as the total heat loss less the heat loss due to evaporation divided by body temperature less the ambient temperature (Cf = [H1 – He]/[Tb – Ta]). However, they are especially sensitive to ambient temperatures below 11 °C (52 °F) and a decrease in flight coordination is seen. Due to the large surface area of the wing, convective heat loss to cool air may be significant enough to chill flight muscles preventing the precise coordination essential for flight.

These bats are nocturnal, roosting during the day in the forest canopy. They rely on camouflage to hide them from predators.[12] Specific species of trees are not selected for roosting, however some roosts may be used for long periods of time. Roosts are generally 20–30 metres (70–100 ft) from the ground.

The main predators of this species are humans and nocturnal and diurnal birds of prey. However, infection by parasites is often the most significant problem for the hammer-headed bat. Adults are often infected with mites and the hepatoparasite, Hepatocystis carpenteri.

Reproduction and mortality

Little is known about reproduction in hammer-headed bats. In some populations breeding is thought to take place semi-annually during the dry seasons. The timing of the dry season varies depending on the locality, but in general there are two breeding seasons, one from June to August and the other from December to February.[12] However, in other populations, breeding is not restricted to dry seasons and occurs during all months of the year.

This species is often cited as a classic model of lek mating.[18] In this type of mating system, males cluster in dense groups at specific locations known as mating arenas.[18] In some populations of hammer-headed bats, males gather along rivers at night and display by rapid wing flapping accompanied by loud vocalizations.[19] An arena may contain from around 25 to 130 males. Females fly through the arena assessing the males. Once the female's choice is made, the female lands on the branch and sits beside the male. Once chosen, the male emits a buzzing call and copulation ensues.

However, some populations of hammer-headed bats do not use the lek mating strategy. Males actively display but are not found clustering in groups.[20] This species is highly polygamous. Some estimates suggest that as few as six percent of the males in a population account for up to seventy-nine percent of the matings.

Females generally produce one offspring at a time. Neither gestation nor time until weaning have been reported for this species. Females mature more quickly than males and are sexually mature after six months. They continue to grow and reach adult size at nine months. Males do not reach sexual maturity until approximately eighteen months of age and they do not obtain their unique facial morphology until twelve months. Compared with other bats, this bat is rather long-lived with an average life expectancy of thirty years in the wild.

Interactions with humans

As pests

There is one record of the hammer-headed bat attacking a live chicken.[21] However, this instance was based on anecdotal evidence and has not been validated in successive studies.[22]

As food

Humans hunt this large bat and consume it as bushmeat.

Disease transmission

The hammer-headed bat is one of three species of African fruit bat that are thought to serve as reservoirs for the Ebola virus.[23] Although antibodies against Ebola virus and fragments of viral RNA have been isolated from these bats, the virus itself has not been, so other species might be more important in its transmission.[24] As of mid-2017, it is not known whether these bats are incidental hosts or a reservoir of Ebola virus infection for humans and other terrestrial mammals.[24]

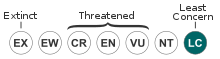

Conservation

As of 2016, it is evaluated as a least-concern species by the IUCN—its lowest conservation priority. It meets the criteria for this classification because it has a wide geographic range; its population is presumably large; and it is not thought to be experiencing rapid population decline.[1]

References

- Tanshi, I. (2016). "Hypsignathus monstrosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019.3: e.T10734A115098825. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T10734A21999919.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |url= mismatch (help)

- Almeida, Francisca C; Giannini, Norberto P; Desalle, Rob; Simmons, Nancy B (2011). "Evolutionary relationships of the old world fruit bats (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae): Another star phylogeny?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 281. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-281. PMC 3199269. PMID 21961908.

- Allen, H. (1861). "Description of new pteropine bats from Africa". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 13: 156–158.

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, T.S. (1904). "Index of Genera and Subgenera". North American Fauna (23): 343.

- Wheeler, W. A. (1872). A Dictionary of the English Language, Explanatory, Pronouncing Etymological, and Synonymous, with Copious Appendix. G & C Merriam.

- Bergmans, W. (1997). "Taxonomy and biogeography of African fruit bats (Mammalia, Megachiroptera). 5. The genera Ussonycteris Andersen, 1912, Myonycteris Matschie, 1899 and Megaloglossus Pagenstecher, 1885; general remarks and conclusions; annex: key to all species". Beaufortia. 47 (2): 11–90.

- Amador, Lucila I.; Moyers Arévalo, R. Leticia; Almeida, Francisca C.; Catalano, Santiago A.; Giannini, Norberto P. (2018). "Bat Systematics in the Light of Unconstrained Analyses of a Comprehensive Molecular Supermatrix". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25: 37–70. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9363-8.

- Cunhaalmeida, Francisca; Giannini, Norberto Pedro; Simmons, Nancy B. (2016). "The Evolutionary History of the African Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Acta Chiropterologica. 18: 73–90. doi:10.3161/15081109ACC2016.18.1.003.

- Nowak, M., R. (1994). Walker's Bats of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 63–64.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2012-07-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Langevin, P.; Barclay, R. (1990). "Hypsignathus monstrosus". Mammalian Species. 357 (357): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3504110. JSTOR 3504110.

- Altringham, D., J. (1996). Bats: Biology and Behaviour. Oxford University Press.

- Courts, S. E. (1998). "Dietary strategies of Old World fruit bats (Megachiroptera, Pteropodidae): how do they obtain sufficient protein?". Mammal Rev. 28 (4): 185–194. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.1998.00033.x.

- Nowak, M., R. (1999). Walker's Bats of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- Eisenberg, J. F.; Wilson, D. E. (1978). "Relative brain size and feeding strategies in the Chiroptera". Evolution. 32 (4): 740–751. doi:10.2307/2407489. JSTOR 2407489. PMID 28567922.

- Carpenter, R. E. (1986). "Flight physiology of intermediate-sized fruit bats (Pteropodidae)". J Exp Biol. 120: 79–103.

- Bradbury, J. W. (1977). "Lek Mating Behavior in the Hammer-headed Bat". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 45 (3): 225–255. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1977.tb02120.x.

- Griffin, R., D. (1986). Communication in the Chiroptera. 61. pp. 284. ISBN 0-253-31381-3.

- Truxton, G. T. (2001). The calling behavior and mating system of a non-lekking population of Hypsignathus monstrosus. Ph.D. dissertation. State University of New York at Stony Brook.

- Deusen, M. van, H. (1968). "Carnivorous Habits of Hypsignathus monstrosus". J. Mammal. 49 (2): 335–336. doi:10.2307/1378006. JSTOR 1378006.

- Bradbury, Jack W. (1977). "Lek Mating Behavior in the Hammer-headed Bat". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 45 (3): 225–255. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1977.tb02120.x.

- Brahic, C. (Nov 30, 2005). "Fruit bats blamed for Ebola outbreaks".

- Kupferschmidt, K. (2017). "Bat patrol". Science. 356 (6341): 901–903. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..901K. doi:10.1126/science.356.6341.901. PMID 28572348.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypsignathus monstrosus. |