Georges Danton

George Jacques Danton (French: [ʒɔʁʒ dɑ̃tɔ̃]; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a leading figure in the early stages of the French Revolution, in particular as the first president of the Committee of Public Safety. Danton's role in the onset of the Revolution has been disputed; many historians describe him as "the chief force in the overthrow of the French monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic".[1]

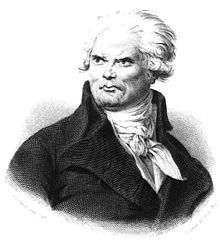

Georges Danton | |

|---|---|

Georges-Jacques Danton. Musée Carnavalet, Paris | |

| Member of the Committee of Public Safety | |

| In office 6 April 1793 – 10 July 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 10 August 1792 – 9 October 1792 | |

| Preceded by | Étienne Dejoly |

| Succeeded by | Dominique Joseph Garat |

| President of the National Convention | |

| In office 25 July 1793 – 8 August 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Jean Bon Saint-André |

| Succeeded by | Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles |

| Member of the National Convention | |

| In office 20 September 1792 – 5 April 1794 | |

| President of the Committee of Public Safety | |

| In office 6 April 1793 – 10 July 1793 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 October 1759 Arcis-sur-Aube, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 5 April 1794 (aged 34) Paris, First French Republic |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Nationality | French |

| Political party | Cordeliers Club (1790–1791) Jacobin Club[1] (1791–1794) |

| Other political affiliations | The Mountain (1792–1794) |

| Spouse(s) | Antoinette Gabrielle Charpentier (m. 1787–1793) ; her deathLouise Sébastienne Gély (m. 1793–1794) ; his death |

| Children | François (1788–1789) Antoine (1790–1858) François Georges (1792–1848) |

| Parents | Jacques Danton and Mary Camus |

| Relatives | Anne Madeleine Danton (1755-1802) (Sister) Marie Nicole Cecile Danton (1757-1814) (Sister) Danton's Family |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

| Signature | |

He was guillotined by the advocates of revolutionary terror after accusations of venality and leniency toward the enemies of the Revolution.

Early life

Danton was born in Arcis-sur-Aube (Champagne in northeastern France) to Jacques Danton, a respectable, but not wealthy lawyer and Mary Camus. As a baby, he was attacked by a bull and run over by pigs, which, along with smallpox, resulted in the disfigurement and scarring his face.[2] He initially attended the school in Sézanne, and at the age of thirteen he left his parents' home to enter the seminary in Troyes. In 1780 he settled in Paris, where he became a clerk. In 1784 he started studying law and in 1787 he became a member of the Conseil du Roi.[3] He married Antoinette Gabrielle Charpentier (6 January 1760 – 10 February 1793) on 14 June 1787 at the church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois. The couple lived in a 6-room apartment in the heart of the Left Bank, (near the Café Procope), and had three sons:

Revolution

From 14 July 1789, the day of the storming of the Bastille, he volunteered in the National Guard. In March 1790 the Paris Commune was divided up in 48 sections and allowed to gather separately. On 27 April 1790 he was elected president of his section, His house was open to many people from the neighborhood. Danton, Desmoulins and Marat, who lived around the corner, all used the nearby Cafe Procope as a meeting place. On 2 August Jean Sylvain Bailly became Paris' first elected mayor; Danton had 49 votes, Marat and Louis XVI only one.[5][6] Robespierre, Pétion, Danton and Brissot dominated the Jacobin Club when the Feuillants founded their own club. In Spring 1791 he suddenly began investing in property, in or near his birthplace, on a large scale.[7] On July 17, 1791, Danton initiated a petition. Robespierre went to the Jacobin club to cancel the draft of the petition, according to Albert Mathiez. Robespierre persuaded the Jacobin clubs not to support the petition by Danton and Brissot.[8] After the Champ de Mars massacre, he escaped from Paris and then lived in London for a few weeks.[9] Since Jean-Paul Marat, Danton and Robespierre were no longer delegates of the Assembly, politics often took place outside the meeting hall. On 9 August Danton came back from Arcis. In the evening before the storming of the Tuileries Danton was visited by Desmoulins, his wife and Fréron. After dinner he went to the Cordeliers and preferred to go to bed early. It seems he went to the Maison-Commune after midnight.[10] The next day he was appointed as minister of justice; he appointed Fabre and Desmoulins as his secretaries. More than a hundred decisions left the department within eight days. On 14 August Danton invited Robespierre to join the Council of Justice. Danton seems to have dined almost every day at the Rolands.[11] On 28 August, the Assembly ordered a curfew for the next two days.[12] On the behest Danton, thirty commissioners from the sections were ordered to search in every suspect house for weapons, munition, swords, carriages and horses.[13][14][15] Before 2 September, between 520–1,000 people were taken into custody on the flimsiest warrants. The exact number of those arrested will never be known.[16] On Sunday 2 September around one, Danton member of the provisional government delivered an speech in the assembly: “We ask that any one refusing to give personal service or to furnish arms shall be punished with death”.[17] “The tocsin we are about to ring is not an alarm signal; it sounds the charge on the enemies of our country. He continued after the applause “To conquer them we must dare, dare again, always dare, and France is saved!”.[18][19] His speech acted as a call for direct action among the citizens, as well as a strike against the external enemy.[20] Many believe this speech was responsible for inciting the September Massacres. It is estimated that around 1,100-1,600 people were murdered. Madame Roland held Danton responsible.[21][22] Danton was accused by the French historians Adolphe Thiers, Alphonse Lamartine, Jules Michelet, Louis Blanc and Edgar Quinet. According to Albert Soboul there is no proof, however, that the massacres were organized by Danton or by anyone else, though it is certain that he did nothing to stop them.[23]

On 6 September he was elected by his section, "Théâtre Français", to be a deputy for the Convention, gathering on 22 September. Danton remained a member of the ministry, though holding both positions was illegal. Danton, Robespierre and Marat were accused of forming a triumvirate.[24] On 26 September Danton was forced to give up his position in the government. Danton stepped down on 9 October. At the end of October Danton defended Robespierre in the Convention of establishing a dictatorship.

On 10 February 1793, while Danton was on a mission in Belgium, his wife died while giving birth to her fourth child, who also died. Danton was so affected by their deaths that he recruited the sculptor Claude André Deseine and brought him to Sainte-Catherine cemetery to exhume Charpentier's body under cover of night and execute a death mask.

On 10 March, Danton supported the foundation of a Revolutionary Tribunal. He proposed to release all the bankruptcy victims from prison and have them join the army. On 6 April the Committee of Public Safety, only nine members, was installed on proposal of Maximin Isnard, who was supported by Georges Danton. Danton was appointed a member of the Committee. On 1 July 1793, Danton married Louise Sébastienne Gély, aged 16, daughter of Marc-Antoine Gély, court usher (huissier-audiencier) at the Parlement de Paris and member of the Club des Cordeliers. On July 10, he was not re-elected as a member of the Committee of Public Safety. On 5 September, Danton argued for a law to give the Sans-culottes a small compensation for attending the twice weekly section meetings, and to provide a gun to every citizen.[25]

Reign of Terror

On 6 September Danton refused to take a seat in the Comité de Salut Public, declaring that he would join no committee, but would be a spur to them all.[27] He believed a stable government was needed which could resist the orders of the Comité de Salut Public.[28] On 10 October Danton, who had been dangerously ill for a few weeks,[29] quit politics, and set off to Arcis-sur-Aube with his 16-year-old wife, who pitied the Queen since her trial began.[30] On 18 November, after the arrest of François Chabot, Edme-Bonaventure Courtois urged Danton to come back to Paris to again play a role in politics.

On 22 November, Danton attacked religious persecution and demanded frugality with human lives. Danton tried to weaken the Terror by attacking Jacques René Hébert. On 3 December Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin club of feigning an illness with the intention to emigrate to Switzerland. Danton showed too often his vices and not his virtue. Robespierre was stopped in his attack. The gathering was closed after an applause for Danton.[31] Danton said he had absolutely no intention of breaking the revolutionary impulse.[32] On 9 December Danton became press because of insider trading with the French East India Company, which threatened to go bankrupt.[33] By December a Dantonist party had been formed.[34] Robespierre replied to Danton's plea for an end to the Terror on 25 December (5 Nivôse, year II).

The French National Convention during the autumn of 1793 began to assert its authority further throughout France, creating the bloodiest period of the French Revolution, in which some historians assert approximately 40,000 people were killed in France.[35] Following the fall of the Girondins, a group known as the Indulgents would emerge from amongst the Montagnards as the legislative right within the Convention and Danton as their most vocal leader. Having long supported the progressive acts of the Committee of Public Safety, Danton would begin to propose that the Committee retract legislation instituting terror as “the order of the day.”[36]

On 26 February 1794, Saint-Just delivered a speech before the Convention in which he directed the assault against Danton, claiming that the Dantonists wanted to slow down the Terror and the Revolution. Self-indulgent over-eating, especially when flaunted in public, was an indication of suspect political loyalties, according to Saint-Just. It seems Danton became exasperated by Robespierre's repeated references to virtue. On 6 March Barère attacked the Hébertists and Dantonists.

While the Committee of Public Safety was concerned with strengthening the centralist policies of the Convention and its own grip over that body, Danton was in the process of devising a plan that would effectively move popular sentiment among delegates towards a more moderate stance.[37] This meant adopting values popular among the sans-culotte, notably the control of bread prices that had seen drastic increase with the famine that was being experienced throughout France. Danton also proposed that the Convention begin taking actions towards peace with foreign powers, as the Committee had declared war on the majority of European powers, such as Britain, Spain, and Portugal. Danton made a triumphant speech announcing the end of the Terror.[38] As Robespierre listened, he was convinced that Danton was pushing for leadership in a post-Terror government. If Robespierre did not counter-attack quickly, the Dantonists could seize control of the National Convention and bring an end to his Republic of Virtue.

The Reign of Terror was not a policy that could be easily transformed. Indeed, it would eventually end with the Thermidorian Reaction (27 July 1794), when the Convention rose against the Committee, executed its leaders, and placed power in the hands of new men with a new policy. But in Germinal—that is, in March 1794—feeling was not ripe. The committees were still too strong to be overthrown, and Danton, heedless, instead of striking with vigor in the Convention, waited to be struck. "In these later days," writes the 1911 Britannica, "a certain discouragement seems to have come over his spirit". His wife had died during his absence on one of his expeditions to the armies; he had her body exhumed so as to see her again.[39] Despite genuine grief, Danton quickly married again, and, the Britannica continues, "the rumour went that he was allowing domestic happiness to tempt him from the keen incessant vigilance proper to the politician in such a crisis." Robespierre even used Danton's well-fed look against him.

Ultimately, Danton himself would become a victim of the Terror. As he attempted to shift the direction of the revolution by collaborating with Camille Desmoulins through the production of Le Vieux Cordelier, a newspaper that called for the end of the official Terror and dechristianization, as well as launching new peace overtures to France's enemies, those who most closely associated themselves with the Committee of Public Safety, among them key figures such as Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Couthon, would search for any reason to indict Danton for counter-revolutionary activities.[40]

Financial corruption and accusations

Toward the end of the Reign of Terror, Danton was accused of various financial misdeeds, as well as using his position within the Revolution for personal gain. Many of his contemporaries commented on Danton's financial success during the Revolution, certain acquisitions of money that he could not adequately explain.[41] Many of the specific accusations directed against him were based on insubstantial or ambiguous evidence.

Between 1791 and 1793, Danton faced many allegations, including taking bribes during the insurrection of August 1792, helping his secretaries to line their pockets, and forging assignats during his mission to Belgium.[42] Perhaps the most compelling evidence of financial corruption was a letter from Mirabeau to Danton in March 1791 that casually referred to 30,000 livres that Danton had received in payment.[42]

During his tenure on the Committee of Public Safety, Danton organized a peace treaty agreement with Sweden. Although the Swedish government never ratified the treaty, on 28 June 1793 the convention voted to pay 4 million livres to the Swedish Regent for diplomatic negotiations. According to Bertrand Barère, a journalist and member of the Convention, Danton had taken a portion of this money which was intended for the Swedish Regent.[43] Barère’s accusation was never supported by any form of evidence.

The most serious accusation, which haunted him during his arrest and formed a chief ground for his execution, was his alleged involvement with a scheme to appropriate the wealth of the French East India Company. During the reign of the Old Regime, the original French East India Company went bankrupt. It was later revived in 1785, backed by royal patronage.[44] The Company eventually fell under the notice of the National Convention for profiteering during the war. The Company was soon liquidated while certain members of the Convention tried to push through a decree that would cause the share prices to rise before the liquidation.[45] Discovery of the profits from this insider trading led to the blackmailing of the directors of the Company to turn over half a million livres to known associates of Danton.[46] While there was no hard evidence that Danton was involved, he was vigorously denounced by François Chabot, and implicated by the fact that Fabre d’Eglantine, a member of the Dantonists, was implicated in the scandal. After Chabot was arrested on 17 November, Courtois urged Danton to return to Paris immediately.

In December 1793 the journalist Camille Desmoulins launched a new journal, Le Vieux Cordelier, attacking François Chabot in the first issue, defending Danton and not to exaggerate the revolution in the second issue, attacking terror, comparing Robespierre with Julius Caesar and arguing that the Revolution should return to its original ideas en vogue around 10 August 1792 in the third issue.[47] Robespierre replied to Danton's plea for an end to the Terror on 25 December (5 Nivôse, year II). Danton continued to defend Fabre d'Eglantine even after the latter had been exposed and arrested.

In February 1794 Danton was exasperated by Robespierre's repeated references to virtue. On 26 February 1794, Saint-Just delivered a speech before the Convention in which he directed the assault against Danton.

At the end of March 1794 Danton made a triumphant speech announcing the end of the Terror.[38] As Robespierre listened, he was convinced that Danton was pushing for leadership in a post-Terror government. If Robespierre did not counter-attack quickly, the Dantonists could seize control of the National Convention and bring an end to his Republic of Virtue. For several months he had resisted killing Danton.[48] According to Linton, Robespierre had to choose between friendship and virtue. His aim was to sow enough doubt in the minds of the deputies regarding Danton's political integrity to make it possible to proceed against him. Robespierre refused to see Desmoulins and rejected a private appeal.[49] Robespierre even used Danton's well-fed look against him. Then Robespierre broke with Danton, who had angered many other members of the Committee of Public Safety with his more moderate views on the Terror, but whom Robespierre had, until this point, persisted in defending.

Arrest, trial, and execution

On 30 March the two committees decided to arrest Danton and Desmoulins, Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles, Pierre Philippeaux without chance to be heard in the Convention.[50] On 2 April the trial began on charges of conspiracy, theft and corruption; a financial scandal involving the French East India Company provided a "convenient pretext" for Danton's downfall.[51] The Dantonists, in Robespierre's eyes, had become false patriots who had preferred personal and foreign interests to the welfare of the nation. Robespierre was sharply critical of Amar's report, which presented the scandal as purely a matter of fraud. Robespierre insisted that it was a foreign plot, demanded that the report be re-written, and used the scandal as the basis for rhetorical attacks on William Pitt the Younger he believed was involved.[52] Louis Legendre suggested to hear Danton in the Convention but Robespierre replied "It would be violating the laws of impartiality to grant to Danton what was refused to others, who had an equal right to make the same demand. This answer silenced at once all solicitations in his favour." [53] No friend of the Dantonists dared speak up in case he too should be accused of putting friendship before virtue.[54] The juror Souberbielle asked himself: "Which of the two, Robespierre or Danton, is the more useful to the Republic?"[55] The death of Hébert had rendered Robespierre master of the Paris Commune; the death of Danton, master of the Convention.[56]

(The directors of the Company were never interrogated at all.[57]) At his trial Danton made such a commotion that Fouquier-Tinville, was unnerved. Saint-Just had a bill rushed through the Convention, cutting off further debate at the Tribunal. Saint-Just helped to pass a law that prevented any accused from speaking in his own defense.

Danton displayed such vehemence before the revolutionary tribunal that his enemies feared he would gain the crowd's favour.[58] The Convention, in one of its "worst fits of cowardice",[59] assented to a proposal made by Louis Antoine de Saint-Just during the trial that, if a prisoner showed want of respect for justice, the tribunal might exclude the prisoner from further proceeding and pronounce sentence in his absence.[60]

Danton, Desmoulins, and many other actual or accused Dantonist associates were tried from 3–5 April before the Revolutionary Tribunal. The trial was less criminal in nature than political, and as such unfolded in an irregular fashion. The jury had only seven members, despite the law demanding twelve, as it was deemed that only seven jurors could be relied on returning the required verdict. During the trial, Danton made lengthy and violent attacks on the Committee of Public Safety. Both his accused associates and he demanded the right to have witnesses appear on their behalf; they submitted requests for several, including, in Desmoulins' case, Robespierre.

The Court's President, M.J.A. Herman, was unable to control the proceedings until the National Convention passed the aforementioned decree, which prevented the accused from further defending themselves. These facts, together with confusing and often incidental denunciations (for instance, a report that Danton, while engaged in political work in Brussels, had appropriated a carriage filled with two or three hundred thousand pounds' worth of table linen)[61] and threats made by prosecutor Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville towards members of the jury, ensured a guilty verdict. Danton and the rest of the defendants were condemned to death, and at once led, in company with fourteen others, including Camille Desmoulins and several other members of the Indulgents, to the guillotine. "I leave it all in a frightful welter," he said; "not a man of them has an idea of government. Robespierre will follow me; he is dragged down by me. Ah, better be a poor fisherman than meddle with the government of men!" The phrase 'a poor fisherman' was almost certainly a reference to Saint Peter, Danton having reconciled to Catholicism.[62]

Danton was one member of a group of fifteen people beheaded on 5 April 1794, a group that included Marie Jean Hérault de Séchelles, Philippe Fabre d'Églantine and Pierre Philippeaux among others; Desmoulins died third and Danton last. Danton and his guillotined associates were buried in the Errancis Cemetery, a common internment location for those executed during the Revolution. In the mid-19th century, their skeletal remains were transferred to the Catacombs of Paris.[63]

On 9 Thermidor when Garnier de l’Aube witnessed Robespierre's inability to respond, he shouted, "The blood of Danton chokes him!"[64] Robespierre then finally regained his voice to reply with his one recorded statement of the morning, a demand to know why he was now being blamed for the other man's death: "Is it Danton you regret? ... Cowards! Why didn't you defend him?"[65]

Character disputes

His influence and character during the French Revolution was, and still is, widely disputed among many historians, with the stretch of perspectives on him ranging from corrupt and violent to generous and patriotic.[66] Danton did not leave very much in the way of written works, personal or political; therefore most information about his actions and personality has been derived from secondhand sources.[67]

One view of Danton, presented by historians like Thiers and Mignet,[68] suggested he was "a gigantic revolutionary" with extravagant passions, a high level of intelligence, and a tolerance of violence for his goals. Another perspective of Danton emerges from the work of Lamartine, who called Danton a man "devoid of honor, principles, and morality" who found only excitement and a chance for distinction during the French Revolution. He was merely "a statesman of materialism" who was bought anew every day. Any revolutionary moments were staged for the prospect of glory and more wealth.[69]

Another view of Danton is presented by Robinet, whose examination of Danton is more positive and portrays him as a figure worthy of admiration. According to Robinet, Danton was a committed, loving, generous citizen, son, father, and husband. He remained loyal to his friends and the country of France by avoiding "personal ambition" and gave himself wholly to the cause of keeping "the government consolidated" for the Republic. He always had a love for his country and the laboring masses, who he felt deserved "dignity, consolation, and happiness".[70]

The 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica wrote that Danton stands out as a master of commanding phrase. One of his fierce sayings has become a proverb. Against the Duke of Brunswick and the invaders, "il nous faut de l'audace, et encore de l'audace, et toujours de l'audace"—"We need audacity, and yet more audacity, and always audacity!".[71]

Fictionalized accounts

- Danton, Robespierre, and Marat are characters in Victor Hugo's novel, Ninety-Three (Quatrevingt-treize), set during the French Revolution.

- Danton is a central character in Romanian playwright Camil Petrescu's play of the same name.

- Danton's last days were made into a play, Dantons Tod (Danton's Death), by Georg Büchner.

- On the basis of Büchner's play, Gottfried von Einem wrote an opera with the same title, on a libretto by himself and Boris Blacher, which premiered on 6 August 1947 at the Salzburger Festspiele.

- Danton appears in the Hungarian play The Tragedy of Man and the animated movie of the same name as one of Adam's incarnations throughout Lucifer's illusion.

- Danton's life from 1791 until his execution was the subject of the 1931 German film, Danton.

- Danton's and Robespierre's quarrels were turned into a 1983 film Danton directed by Andrzej Wajda. The film itself is loosely based on Stanisława Przybyszewska's 1929 play "Sprawa Dantona" ("The Danton Case").

- Danton's and Robespierre's relations were also the subject of an opera by American composer John Eaton, Danton and Robespierre (1978).

- Danton is extensively featured in La Révolution française (1989),[72].

- In his novel Locus Solus, Raymond Roussel tells a story in which Danton makes an arrangement with his executioner for his head to be smuggled into his friend's possession after his execution. The nerves and musculature of the head ultimately end up on display in the private collection of Martial Canterel, reanimated by special electrical currents and showing a deeply entrenched disposition toward oratory.

- The Revolution as experienced by Danton, Robespierre, and Desmoulins is the central focus of Hilary Mantel's novel A Place of Greater Safety (1993).

- Danton and Camille Desmoulins are the main characters of Tanith Lee's The Gods Are Thirsty—A Novel of the French Revolution (1996).

- Danton and Maximilien Robespierre are referred to in the book The Scarlet Pimpernel briefly. Danton and Robespierre both applaud a guard for his work in catching aristocrats.

- In The Tangled Thread, Volume 10 of The Morland Dynasty, a series of historical novels by author Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, the character Henri-Marie Fitzjames Stuart, bastard offshoot of the fictional Morland family, allies himself with Danton in an attempt to protect his family as the storm clouds of revolution gather over France.

- Danton appears briefly in Rafael Sabatini's adventure novel Scaramouche: A tale of romance in the French Revolution.

- Danton appears in a series of comics entitled "The Last Days of Georges Danton" in Step Aside, Pops: A Hark! A Vagrant Collection by Kate Beaton.[73]

- Danton is one of six point-of-view characters in Marge Piercy's novel City of Darkness, City of Light (1996).

- Danton, along with Marat and Robespierre, is a secondary character in the 1927 epic Napoléon. His portrayal in the film is somewhat cartoonish, as he is depicted as a decadent fop, albeit dedicated to republicanism and revolution, and it is he that allows Rouget de Lisle to premiere "La Marseillaise" at the Club des Cordeliers. (In reality, no such performance by Rouget de Lisle is known to have taken place.)[74]

References

- "Georges Danton profile". Britannica.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The French Revolution. Penguin UK. p. 384. ISBN 9780141927152.

- Hampson, Norman. Danton (New York: Basil Blackwell Inc., 1988), pp. 19–25.

- "Family tree Claude FORMA - Geneanet". gw.geneanet.org. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Petites et Grandes Révolutions de la Famille de Milly: Recherches sur et ... by Alexandre Blondet, p. 181, 185

- Les lundis révolutionnaires: 1790 by Jean-Bernard, p. 250-251

- N. Hampson (1978) Danton, p. 57

- Schama 1989, p. 567.

- Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), p. 51.

- N. Hampson (1978) Danton, p. 72-73

- N. Hampson (1978) Danton, p. 76

- Jean Massin (1959) Robespierre, pp. 133–34

- S. Schama, p. 626

- Collection Complète des Lois, Décrets, Ordonnances, Réglements, p. 440

- "The journée of 20 June, the Brunswick Manifesto, the taking of the Tuileries, the end of the monarchy, the September massacres - A People's History of the French Revolution". Erenow.net.

- S. Loomis, p. 77

- Assemblée Nationale

- The World’s Famous Orations. Continental Europe (380–1906). 1906.

- Discours de Danton : Edition critique par André Fribourg, p. 172. Paris Au siége de la Société 1910.

- Hillary Mantel in London Review of Books

- Watanabe-O'Kelly, H. (2018) From Viragos to Valkyries Transformations of the Heroic Warrior Woman in German literature from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century. In: Tracing the Heroic Through Gender

- The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, A Life by David Lawday

- Britannica.com

- Robespierre, Maximilien; Laponneraye, Albert; Carrel, Armand (1840). Oeuvres. Worms. p. 98.

- Soboul, A. (1975) De Franse Revolutie dl I, 1789-1793, p. 283.

- The Monthly Review. Printed for R. Griffiths. 1814. p. 386. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

danton height looks.

- R.R. Palmer (1970) The Twelve who ruled, p. 256

- Histoire de la revolution Française, Volume 8 by Jules Michelet, p. 33-34, 53

- Feuille du salut public 4 octobre 1793, p.

- "Georges Danton | French revolutionary leader". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Le Moniteur Universel 6/12/1793

- Soboul, A. (1975) De Franse Revolutie dl I, 1789-1793, p. 308.

- Soboul, A. (1975) De Franse Revolutie dl I, 1789-1793, p. 310.

- R.R. Palmer (1970) The Twelve who ruled, p. 256

- Greer, Donald (1935). The Incidence of the Terror During the French Revolution: A Statistical Interpretation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-8446-1211-9.

- French National Convention. "Terror is the Order of the Day". Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- Andress, David (2005). The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-374-53073-0.

- Schama 1989, p. 816-817.

- Beesly, A.H. (2005). Life of Danton. Kessinger Publishing. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-4179-5724-8. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Andress, David (2005). The Terror: The Merciless Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-374-53073-0.

- Hampson, Norman, The Life and Opinions of Maximilien Robespierre (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., 1974), p. 204

- Hampson, Norman, The Life and Opinions of Maximilien Robespierre (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., 1974), p. 204.

- Hampson, Norman, Danton (New York: Basil Blackwell Inc., 1988), 121

- Scurr, Ruth, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks, 2006), 301.

- Scurr, Ruth, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks, 2006), 301.

- Andress, David, The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 252.

- Funck, F.; Danton, G.J.; Châlier, M.J. (1843). 1793: Beitrag zur geheimen Geschichte der französischen Revolution, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Danton's und Challier's, zugleich als Berichtigung der in den Werken von Thiers und Mignet enthaltenen Schilderungen (in German). F. Bassermann. p. 52.

- Linton 2013, p. 219.

- Linton 2013, p. 222.

- Linton 2013, p. 225.

- W. Doyle (1990) The Oxford History of the French Revolution, pp. 272–74.

- Matrat, J. Robespierre Angus & Robertson 1971 p. 242

- Annual Register, Band 36. Published by Edmund Burke, p. 118

- Linton 2013, p. 226.

- Hampson 1974, p. 222-223, 258.

- Lamartine, Alphonse de (9 September 1848). "History of the Girondists: Or, Personal Memoirs of the Patriots of the French Revolution". Henry G. Bohn – via Google Books.

- Hampson 1974, p. 219.

- "Danton Versus Robespierre: The Quest for Revolutionary Power". www.ucumberlands.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- 1911 Britannica

- Schama, Simon. Citizens.

- Claretie, Jules (1876). Camille Desmoulins and his wife. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 313.

Camille Desmoulins and his wife.

- Carrol, Warren, The Guillotine and the Cross (Front Royal, Christendom Press, 1991)

- Beyern, B., Guide des tombes d'hommes célèbres, Le Cherche Midi, 2008, 377p, ISBN 978-2-7491-1350-0

- Schama 1989, pp. 842–44.

- Korngold, Ralph 1941, p. 365, Robespierre and the Fourth Estate Retrieved 27 July 2014

- Hampson, Norman, Danton (New York: Basil Blackwell), pp. 1–7.

- F.C. Montague, reviewer of Discours de Danton by André Fribourg, The English Historical Review 26, No. 102 (1911), 396. JSTOR 550513.

- Legrand, Jacques. Chronicle of the French Revolution 1788–1799, London: Longman, 1989.

- Furet, François. La révolution en debat, Paris: Gallimard, 1999.

- Henri Béraud, Twelve Portraits of the French Revolution, (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1968).

- Serres, Eric (2017-07-10). "« De l'audace, encore de l'audace, toujours de l'audace ! » Danton n'en manqua point". L'Humanité. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

Nous demandons qu’il soit fait une instruction aux citoyens pour diriger leurs mouvements. Nous demandons qu’il soit envoyé des courriers dans tous les départements pour avertir des décrets que vous aurez rendus – le tocsin qu’on va sonner n’est point un signal d’alarme, c’est la charge sur les ennemis de la patrie. Pour les vaincre, il nous faut de l’audace, encore de l’audace, toujours de l’audace, et la France est sauvée.

- "La révolution française". 25 October 1989 – via IMDb.

- Beaton, Kate (2013). Step Aside, Pops: A Hark! A Vagrant Collection. Canada: Drawn and Quarterly. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1-77046-208-3.

- "Napoleon". 1927 – via IMDb.

Sources

Further reading

- François Furet and Mona Ozouf (eds.), A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1989; pp. 213–223.

- Laurence Gronlund, Ça Ira! or Danton in the French Revolution. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1887.

- Norman Hampson, Danton. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1978.

- David Lawday, Danton: The Giant of the French Revolution. London: Jonathan Cape, 2009.

- Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- A Letter from Danton to Marie Antoinette by Carl Becker. In: The American Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Oct. 1921), p. 29 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association JSTOR 1836918

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georges Danton. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Georges Danton |

- Works by Georges Jacques Danton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Georges Danton at Internet Archive

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Etienne Dejoly |

Minister of Justice 1792 |

Succeeded by Dominique Joseph Garat |

�