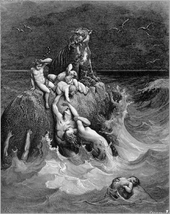

Genesis flood narrative

The Genesis flood narrative is a flood myth[lower-alpha 1] found in the Tanakh (chapters 6–9 in the Book of Genesis).[1] The story tells of God's decision to return the Earth to its pre-creation state of watery chaos and then remake it in a reversal of creation.[2] The narrative has very strong similarities to parts of the Epic of Gilgamesh which predates the Book of Genesis.

A global flood as described in this myth is inconsistent with the physical findings of geology and paleontology.[3][4] A branch of creationism known as flood geology is a pseudoscientific attempt to argue that such a global flood actually occurred.[5]

Composition

Sources

The flood is part of what scholars call the primeval history, the first 11 chapters of Genesis.[6] These chapters, fable-like and legendary, form a preface to the patriarchal narratives which follow, but show little relationship to them.[7][6][8] For example, the names of its characters and its geography—Adam ("Man") and Eve ("Life"), the Land of Nod ("Wandering"), and so on—are symbolic rather than real, and much of the narratives consist of lists of "firsts": the first murder, the first wine, the first empire-builder.[9] Few of the people, places and events depicted in the book are mentioned elsewhere in the Bible.[9] This has led scholars to suppose that the primeval history forms a late composition attached to Genesis to serve as an introduction.[10] At one extreme are those who see it as a product of the Hellenistic period, in which case it cannot be earlier than the first decades of the 4th century BCE;[11] on the other hand the Yahwist source has been dated by others, notably John Van Seters, to the exilic pre-Persian period (the 6th century BCE), precisely because the primeval history contains so much Babylonian influence in the form of myth.[12][lower-alpha 2]

The flood narrative is made up of two stories woven together.[13] As a result many details are contradictory, such as how long the flood lasted (40 days according to Genesis 7:17, 150 according to 7:24), how many animals were to be taken aboard the ark (one pair of each in 6:19, one pair of the unclean animals and seven pairs of the clean in 7:2), and whether Noah released a raven which "went to and fro until the waters were dried up" or a dove which on the third occasion "did not return to him again," or possibly both.[14] Despite this disagreement on details the story forms a unified whole (some scholars see in it a "chiasm", a literary structure in which the first item matches the last, the second the second-last, and so on),[lower-alpha 3] and many efforts have been made to explain this unity, including attempts to identify which of the two sources was earlier and therefore influenced the other.[15][lower-alpha 4]

Comparative mythology

The flood myth originated in Mesopotamia.[16] The Mesopotamian story has three distinct versions, the Sumerian Epic of Ziusudra, (the oldest, dating from about 1600 BCE), and as episodes in two Babylonian epics, those of Atrahasis and Gilgamesh.[17]

Genesis 6:9–9:17

Summary

Noah was a righteous man and walked with God. Seeing that the earth was corrupt and filled with violence, God instructed Noah to build an ark in which he, his sons, and their wives, together with male and female of all living creatures, would be saved from the waters. Noah entered the ark in his six hundredth year, and on the 17th day of the second month of that year "the fountains of the Great Deep burst apart and the floodgates of heaven broke open" and rain fell for forty days and forty nights until the highest mountains were covered 15 cubits, and all earth-based life perished except Noah and those with him in the ark.

In Jewish legend, the kind of water that was pouring to the earth for forty days is not the common, but God bade each drop pass through Hell of Gehenna before it fell to earth, and the 'hot rain' scalded the skin of the sinners. The punishment that overtook them was befitting their crime. As their sensual desires had made them hot, and inflamed them to immoral excesses, so they were chastised by means of heated water.[18]

After 150 days, "God remembered Noah ... and the waters subsided" until the ark rested on the mountains of Ararat. On the 27th day of the second month of Noah's six hundred and first year the earth was dry. Then Noah built an altar and made a sacrifice, and God made a covenant with Noah that man would be allowed to eat every living thing but not its blood, and that God would never again destroy all life by a flood.

The flood and the creation narrative

The flood is a reversal and renewal of God's creation of the world.[19] In Genesis 1 God separates the "waters above the earth" from those below so that dry land can appear as a home for living things, but in the flood story the "windows of heaven" and "fountains of the deep" are opened so that the world is returned to the watery chaos of the time before creation.[20] Even the sequence of flood events mimics that of creation, the flood first covering the earth to the highest mountains, then destroying, in order, birds, cattle, beasts, "swarming creatures", and finally mankind.[20] (This parallels the Babylonian flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where at the end of rain "all of mankind had returned to clay," the substance of which they had been made).[21] The ark itself is likewise a microcosm of Solomon's Temple.

Intertextuality

Intertextuality is the way biblical stories refer to and reflect one another. Such echoes are seldom coincidental—for instance, the word used for ark is the same used for the basket in which Moses is saved, implying a symmetry between the stories of two divinely chosen saviours in a world threatened by water and chaos.[22] The most significant such echo is a reversal of the Genesis creation narrative; the division between the "waters above" and the "waters below" the earth is removed, the dry land is flooded, most life is destroyed, and only Noah and those with him survive to obey God's command to "be fruitful and multiply."[23]

Religious views

Christianity

The Genesis flood narrative is included in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible (see Books of the Bible). Jesus and the apostles additionally taught on the Genesis flood narrative in New Testament writing (Matthew 24:37-39, Luke 17:26-27, 1 Peter 3:20, 2 Peter 2:5, 2 Peter 3:6, Hebrews 11:7).[24][25] Some Christian biblical scholars suggest that the flood is a picture of salvation in Christ—the ark was planned by God and there is only one way of salvation through the door of the ark, akin to one way of salvation through Christ.[26][27] Additionally, some scholars commenting on the teaching of the apostle Peter (1 Peter 3:18-22), connect the ark with the resurrection of Christ; the waters burying the old world but raising Noah to a new life.[26][27] Christian scholars also highlight that 1 Peter 3:18-22 demonstrates the Genesis flood as a type to Christian baptism.[28][29][24]

Islam

The Quran states that Noah (Nūḥ) was inspired by God, believed in the oneness of God, and preached Islam.[30] God commanded Noah to build an ark. As he was building it, the chieftains passed him and mocked him. Upon its completion, the ark was loaded with the animals in Noah's care as well as his immediate household.[31] The people who denied the message of Noah, including one of his own sons, drowned.[32] The final resting place of the ark was referred to as Mount Judi.[33]

Historicity

While some scholars have tried to offer possible explanations for the origins of the flood myth including a legendary retelling of a possible Black Sea deluge, the general mythological exaggeration and implausibility of the story are widely recognized by relevant academic fields. The acknowledgement of this follows closely the development of understanding of the natural history and especially the geology and paleontology of the planet.[3][34]

Setting

The Masoretic Text of the Torah places the Great Deluge 1,656 years after Creation, or 1656 AM (Anno Mundi, "Year of the World"). Many attempts have been made to place this time-span at a specific date in history.[35] At the turn of the 17th century CE, Joseph Scaliger placed Creation at 3950 BCE, Petavius calculated 3982 BCE,[36][37] and according to James Ussher's chronology, Creation took place in 4004 BCE, dating the Great Deluge to 2348 BCE.[38]

Flood geology

The development of scientific geology had a profound impact on attitudes towards the biblical flood narrative. By bringing into question the biblical chronology, which placed the Creation and the Flood in a history which stretched back no more than a few thousand years, the concept of deep geological time undermined the idea of the historicity of the ark itself. In 1823 the English theologian and natural scientist William Buckland interpreted geological phenomena as Reliquiae Diluvianae: "relics of the flood" which "attested the action of a universal deluge". His views were supported by others at the time, including the influential geologist Adam Sedgwick, but by 1830 Sedgwick considered that the evidence suggested only local floods. Louis Agassiz subsequently explained such deposits as the results of glaciation.[39]

In 1862, William Thomson (later to become Lord Kelvin) calculated the age of the Earth at between 24 million and 400 million years, and for the remainder of the 19th century, discussion focused not on the viability of this theory of deep time, but on the derivation of a more precise figure for the age of the Earth.[40] Lux Mundi, an 1889 volume of theological essays which is usually held to mark a stage in the acceptance of a more critical approach to scripture, took the stance that readers should rely on the gospels as completely historical, but should not take the earlier chapters of Genesis literally.[41] By a variety of independent means, scientists have determined that the Earth is approximately 4.54 billion years old.

The scientific community regards flood geology as pseudoscience because it contradicts a variety of facts in geology, stratigraphy, geophysics, physics, paleontology, biology, anthropology, and archeology.[5][42][3] Modern geology, its sub-disciplines and other scientific disciplines utilize the scientific method to analyze the geology of the earth. Scientific analysis refutes the key tenets of flood geology, which, as an idea, is in contradiction to scientific consensus.[43][44][45][46][47] Modern geology relies on a number of established principles, one of the most important of which is Charles Lyell's principle of uniformitarianism. In relation to geological forces, uniformitarianism holds that the shaping of the Earth has occurred by means of mostly slow-acting forces that can be seen in operation today. In general, there is a lack of any evidence for any of the above effects proposed by flood geologists, and scientists do not take their claims of fossil-layering seriously.[48]

Species distribution

By the 17th century, believers in the Genesis account faced the issue of reconciling the exploration of the New World and increased awareness of the global distribution of species with the older scenario whereby all life had sprung from a single point of origin on the slopes of Mount Ararat. The obvious answer involved mankind spreading over the continents following the destruction of the Tower of Babel and taking animals along, yet some of the results seemed peculiar. In 1646 Sir Thomas Browne wondered why the natives of North America had taken rattlesnakes with them, but not horses: "How America abounded with Beasts of prey and noxious Animals, yet contained not in that necessary Creature, a Horse, is very strange".[49]

Browne, among the first to question the notion of spontaneous generation, was a medical doctor and amateur scientist making this observation in passing. However, biblical scholars of the time, such as Justus Lipsius (1547–1606) and Athanasius Kircher (c.1601–80), had also begun to subject the Ark story to rigorous scrutiny as they attempted to harmonize the biblical account with the growing body of natural historical knowledge. The resulting hypotheses provided an important impetus to the study of the geographical distribution of plants and animals, and indirectly spurred the emergence of biogeography in the 18th century. Natural historians began to draw connections between climates and the animals and plants adapted to them. One influential theory held that the biblical Ararat was striped with varying climatic zones, and as climate changed, the associated animals moved as well, eventually spreading to repopulate the globe.[49]

There was also the problem of an ever-expanding number of known species: for Kircher and earlier natural historians, there was little problem finding room for all known animal species in the ark. Less than a century later, discoveries of new species made it increasingly difficult to justify a literal interpretation for the Ark story.[50] By the middle of the 18th century only a few natural historians accepted a literal interpretation of the narrative.[51]

See also

- Noah's Ark

- Biblical cosmology

- Chronology of the Bible

- Noach (parsha)

- Panbabylonism

References

Footnotes

- The term myth is used here in its academic sense, meaning "a traditional story consisting of events that are ostensibly historical, though often supernatural, explaining the origins of a cultural practice or natural phenomenon." It is not being used to mean "something that is false".

- See John Van Seters, Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis (1992), pp. 80, 155-56.

- The controversial existence of a chiasm is not an argument against the construction of the story from two sources. See the overview in R.E. Friedman (1996), p. 91.

- The two sources are the Priestly and the Yahwist or "non-priestly". See Bill Arnold, "Genesis" (2009), p. 97.

Citations

- Leeming 2010, p. 469.

- Bandstra 2009, p. 61.

- Montgomery 2012.

-

- Kuchment, Anna (August 2012). "The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Scientific American. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Raff, Rudolf A. (20 January 2013). "Genesis meets geology. A review of the rocks don't lie; a geologist investigates Noah's flood, by David R. Montgomery". Evolution & Development. 15 (1): 83–84. doi:10.1111/ede.12017.

- "The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Publishers Weekly. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Bork, Kennard B. (December 2013). "David R. Montgomery. The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Isis. 104 (4): 828–829. doi:10.1086/676345.

- McConnachie, James (31 August 2013). "The Rocks Don't Lie, by David R. Montgomery - review". The Spectator. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Prothero, Donald R. (2 January 2013). "A Gentle Journey Through the Truth in Rocks". Skeptic. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Isaak, Mark. The Counter-Creationism Handbook. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

- Cline 2007, p. 13.

- Alter 2008, p. 13-14.

- Sailhamer 2010, p. 301 and fn.35.

- Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 2.

- Sailhamer 2010, p. 301.

- Gmirkin 2006, p. 240-241.

- Gmirkin 2006, p. 6.

- Cline 2007, p. 19.

- Cline 2007, p. 20— Which was it—40 or 150 days? ... And how many animals ... One pair of each ... Or seven pairs of each ... And did he release a raven ... until the waters were dried up ... or did he release a dove three different times ... ?

- Arnold 2009, p. 97.

- Chen 2013, p. 1.

- Finkel 2014, p. 88.

- Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I : The Inmates of the Ark (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- Baden 2012, p. 184.

- Keiser 2013, p. 133.

- Keiser 2013, p. 133 fn.29.

- Bodner 2016, p. 95-96.

- Levenson 1988, p. 10-11.

- "Flood, the - Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology Online". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Creation Worldview Ministries: The New Testament and the Genesis Flood: A Hermeneutical Investigation of the Historicity, Scope, and Theological Purpose of the Noahic Deluge". www.creationworldview.org. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- W., Wiersbe, Warren (1993). Wiersbe's expository outlines on the Old Testament. Wheaton, Ill.: Victor Books. ISBN 978-0896938472. OCLC 27034975.

- "Flood, the - Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology Online". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Matthew., Henry (2000). Matthew henry's concise commentary on the whole bible : nelson's concise series. [Place of publication not identified]: Nelson Reference & Electr. ISBN 978-0785245292. OCLC 947797222.

- "The Typological Interpretation of the Old Testament, by G.R. Schmeling". www.bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Quran 4:163, Quran 26:105–107

- Quran 11:35–41

- Quran 7:64

- Quran 11:44

- Weber, Christopher Gregory (1980). "The Fatal Flaws of Flood Geology". Creation Evolution Journal. 1 (1): 24–37.

- Timeline for the Flood. AiG, 9 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- Barr 1984–85, 582.

- Davis A. Young, Ralph F. Stearley, The Bible, Rocks, and Time: Geological Evidence for the Age of the Earth, p. 45.

- James Barr, 1984–85. "Why the World Was Created in 4004 BC: Archbishop Ussher and Biblical Chronology", Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 67:604 PDF document

- Herbert, Sandra (1991). "Charles Darwin as a prospective geological author". British Journal for the History of Science (24). pp. 171–174. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- Dalrymple 1991, pp. 14–17

- James Barr (4 March 1987). Biblical Chronology, Fact or Fiction? (PDF). The Ethel M. Wood Lecture 1987. University of London. p. 17. ISBN 978-0718708641. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- Senter, Phil. "The Defeat of Flood Geology by Flood Geology." Reports of the National Center for Science Education 31:3 (May–June 2011). Printed electronically by California State University, Northridge. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Young 1995.

- Isaak 2006.

- Morton 2001.

- Isaak 2007, p. 173.

- Stewart 2010, p. 123.

- Isaak 1998.

- Cohn 1999.

- Browne 1983, p. 276.

- Young 1995, p. History of the Collapse of "Flood Geology" and a Young Earth.

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert (2008). The Five Books of Moses. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393070248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Bill T. (2009). Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521000673.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300152647.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2009). Reading the Old Testament : an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0495391050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A discursive commentary on Genesis 1-11. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-37287-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chen, Y.C. (2013). The Primeval Flood Catastrophe: Origins and Early Development in Mesopotamian Traditions. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199676200.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohn, Norman (1999). Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300076486.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotter, David W. (2003). Genesis. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814650400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finkel, Irving (2014). The Ark Before Noah. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781444757071.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Richard E. (1996). "Non-Arguments Concerning the Documentary Hypothesis". In Fox, Michael V.; Hurowitz, V. A. (eds.). Texts, Temples and Traditions. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gmirkin, Russell E. (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567134394.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Habel, Norman C. (1988). "Two Flood Myths". In Dundes, Alan (ed.). The Flood Myth. University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keiser, Thomas A. (2013). Genesis 1-11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological Message. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781625640925.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leeming, David A. (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841749.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: introduction and annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195297515.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Middleton, J. Richard (2005). The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1. Brazos Press. ISBN 9781441242785.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montgomery, David R. (2012). The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood. Norton. ISBN 9780393082395.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sailhamer, John H. (2010). The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830878888.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The book of Genesis: chapters 1–17. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825216.

- Kessler, Martin; Deurloo, Karel Adriaan (2004). A commentary on Genesis: the book of beginnings. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809142057.

- McKeown, James (2008). Genesis. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827050.

- Rogerson, John William (1991). Genesis 1–11. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567083388.

- Sacks, Robert D (1990). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Edwin Mellen.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). "Genesis". In James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans.

- Whybray, R.N (2001). "Genesis". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press.