Disneyland

Disneyland Park, originally Disneyland, is the first of two theme parks built at the Disneyland Resort in Anaheim, California, opened on July 17, 1955. It is the only theme park designed and built to completion under the direct supervision of Walt Disney. It was originally the only attraction on the property; its official name was changed to Disneyland Park to distinguish it from the expanding complex in the 1990s. It was the first Disney theme park.

| |

The park's icon, Sleeping Beauty Castle, in 2019. | |

| Slogan | The happiest place on earth |

|---|---|

| Location | Disneyland Resort, 1313 Disneyland Dr, Anaheim, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 33.81°N 117.92°W |

| Theme | Fairy tales and Disney characters |

| Owner | Disney Parks, Experiences and Products (The Walt Disney Company) |

| Operated by | Disneyland Resort |

| Opened | July 17, 1955[1] |

| Previous names | Disneyland (1955–1998) |

| Operating season | Year-round |

| Website | Official website |

| Disneyland Resort |

|---|

| Theme parks |

|

| Hotels |

|

| Other attractions |

|

Walt Disney came up with the concept of Disneyland after visiting various amusement parks with his daughters in the 1930s and 1940s. He initially envisioned building a tourist attraction adjacent to his studios in Burbank to entertain fans who wished to visit; however, he soon realized that the proposed site was too small. After hiring a consultant to help him determine an appropriate site for his project, Disney bought a 160-acre (65 ha) site near Anaheim in 1953. Construction began in 1954 and the park was unveiled during a special televised press event on the ABC Television Network on July 17, 1955.

Since its opening, Disneyland has undergone expansions and major renovations, including the addition of New Orleans Square in 1966, Bear Country (now Critter Country) in 1972, Mickey's Toontown in 1993, and Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge in 2019.[2] Opened in 2001, Disney California Adventure Park was built on the site of Disneyland's original parking lot.

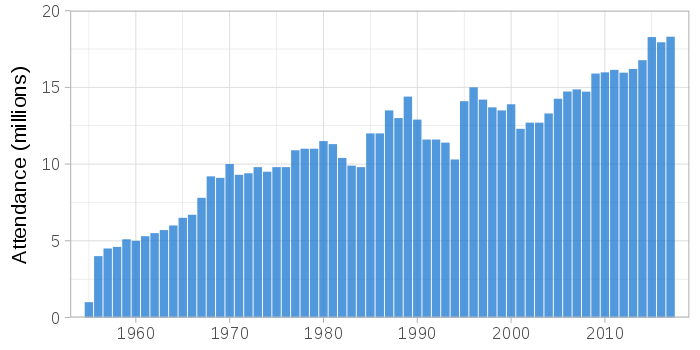

Disneyland has a larger cumulative attendance than any other theme park in the world, with 726 million visits since it opened (as of December 2018). In 2018, the park had approximately 18.6 million visits, making it the second most visited amusement park in the world that year, behind only Magic Kingdom, the very park it inspired.[3] According to a March 2005 Disney report, 65,700 jobs are supported by the Disneyland Resort, including about 20,000 direct Disney employees and 3,800 third-party employees (independent contractors or their employees).[4] Disney announced "Project Stardust" in 2019, which included major structural renovations to the park to account for higher attendance numbers.[5]

History

Walter E. Disney, July 17, 1955[6][7][8][9]

20th century

Origins

The concept for Disneyland began when Walt Disney was visiting Griffith Park in Los Angeles with his daughters Diane and Sharon. While watching them ride the merry-go-round, he came up with the idea of a place where adults and their children could go and have fun together, though his dream lay dormant for many years.[10] He may have also been influenced by his father's memories of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago (his father worked at the Exposition). The Midway Plaisance there included a set of attractions representing various countries from around the world and others representing various periods of man; it also included many rides including the first Ferris wheel, a "sky" ride, a passenger train that circled the perimeter, and a Wild West Show. Another likely influence was Benton Harbor, Michigan's nationally famous House of David's Eden Springs Park. Disney visited the park and ultimately bought one of the older miniature trains originally used there; the colony had the largest miniature railway setup in the world at the time.[11] The earliest documented draft of Disney's plans was sent as a memo to studio production designer Dick Kelsey on August 31, 1948, where it was referred to as a "Mickey Mouse Park", based on notes Disney made during his and Ward Kimball's trip to Chicago Railroad Fair the same month, with a two-day stop in Henry Ford's Museum and Greenfield Village, a place with attractions like a Main Street and steamboat rides, which he had visited eight years earlier.[12][13][14][15]

While people wrote letters to Disney about visiting the Walt Disney Studios, he realized that a functional movie studio had little to offer to visiting fans, and began to foster ideas of building a site near the Burbank studios for tourists to visit. His ideas evolved to a small play park with a boat ride and other themed areas. The initial concept, the Mickey Mouse Park, started with an eight-acre (3.2 ha) plot across Riverside Drive. He started to visit other parks for inspiration and ideas, including Tivoli Gardens in Denmark, Efteling in the Netherlands, and Greenfield Village, Playland, and Children's Fairyland in the United States; and (according to the film director Ken Annakin, in his autobiography 'So You want to be a film director?'), Bekonscot Model Village & Railway, Beaconsfield, England. His designers began working on concepts, though the project grew much larger than the land could hold.[16] Disney hired Harrison Price from Stanford Research Institute to gauge the proper area to locate the theme park based on the area's potential growth. Based on Price's analysis (for which he would be recognized as a Disney Legend in 2003), Disney acquired 160 acres (65 ha) of orange groves and walnut trees in Anaheim, southeast of Los Angeles in neighboring Orange County.[16][17] The Burbank site originally considered by Disney is now home to Walt Disney Animation Studios and ABC Studios.

Difficulties in obtaining funding prompted Disney to investigate new methods of fundraising, and he decided to create a show named Disneyland. It was broadcast on then-fledgling ABC. In return, the network agreed to help finance the park. For its first five years of operation, Disneyland was owned by Disneyland, Inc., which was jointly owned by Walt Disney Productions, Walt Disney, Western Publishing and ABC.[18] In addition, Disney rented out many of the shops on Main Street, U.S.A. to outside companies. By 1960, Walt Disney Productions bought out all other shares, a partnership which would eventually lead to the Walt Disney Corporation's acquisition of ABC in the mid-1990s. Construction began on July 16, 1954 and cost $17 million to complete (equivalent to $129 million in 2018[19]). The park was opened one year and one day later.[20] U.S. Route 101 (later Interstate 5) was under construction at the same time just north of the site; in preparation for the traffic Disneyland was expected to bring, two more lanes were added to the freeway before the park was finished.[17]

Opening day

Disneyland was dedicated at an "International Press Preview" event held on Sunday, July 17, 1955, which was open only to invited guests and the media. Although 28,000 people attended the event, only about half of those were invitees, the rest having purchased counterfeit tickets,[21] or even sneaked into the park by climbing over the fence.[22] The following day, it opened to the public, featuring twenty attractions. The Special Sunday events, including the dedication, were televised nationwide and anchored by three of Walt Disney's friends from Hollywood: Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings, and Ronald Reagan. ABC broadcast the event live, during which many guests tripped over the television camera cables.[23] In Frontierland, a camera caught Cummings kissing a dancer. When Disney started to read the plaque for Tomorrowland, he read partway then stopped when a technician off-camera said something to him, and after realizing he was on-air, said, "I thought I got a signal",[23] and began the dedication from the start. At one point, while in Fantasyland, Linkletter tried to give coverage to Cummings, who was on the pirate ship. He was not ready, and tried to give the coverage back to Linkletter, who had lost his microphone. Cummings then did a play-by-play of him trying to find it in front of Mr. Toad's Wild Ride.[23]

Traffic was delayed on the two-lane Harbor Boulevard.[23] Famous figures who were scheduled to show up every two hours showed up all at once. The temperature was an unusually high 101 °F (38 °C), and because of a local plumbers' strike, Disney was given a choice of having working drinking fountains or running toilets. He chose the latter, leaving many drinking fountains dry. This generated negative publicity since Pepsi sponsored the park's opening; disappointed guests believed the inoperable fountains were a cynical way to sell soda, while other vendors ran out of food. The asphalt that had been poured that morning was soft enough to let women's high-heeled shoes sink into it. Some parents threw their children over the crowd's shoulders to get them onto rides, such as the King Arthur Carrousel.[24] In later years, Disney and his 1955 executives referred to July 17, 1955, as "Black Sunday". After the extremely negative press from the preview opening, Walt Disney invited attendees back for a private "second day" to experience Disneyland properly.

At the time, and during the lifetimes of Walt and Roy Disney, July 17 was considered merely a preview, with July 18 the official opening day.[22] Since then, aided by memories of the television broadcast, the company has adopted July 17 as the official date, the one commemorated every year as Disneyland's birthday.[22]

1950s and 1960s

In September 1959, Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev spent thirteen days in the United States, with two requests: to visit Disneyland and to meet John Wayne, Hollywood's top box-office draw. Due to the Cold War tension and security concerns, he was famously denied an excursion to Disneyland.[25] The Shah of Iran and Empress Farah were invited to Disneyland by Walt Disney in the early 1960s.[26] There was moderate controversy over the lack of African American employees. As late as 1963, civil rights activists were pressuring Disneyland to hire black people,[27] with executives responding that they would "consider" the requests. The park did however hire people of Asian descent, such as Ty Wong and Bob Kuwahara.[28]

As part of the Casa de Fritos operation at Disneyland, "Doritos" (Spanish for "little golden things") were created at the park to recycle old tortillas that would have been discarded. The Frito-Lay Company saw the popularity of the item and began selling them regionally in 1964, and then nationwide in 1966.[29]

1980s

On December 5, 1985, to celebrate Disneyland's 30th year in operation, one million balloons were launched along the streets bordering Disneyland as part of the Skyfest Celebration.[30]

1990s

In the late 1990s, work began to expand the one-park, one-hotel property. Disneyland Park, the Disneyland Hotel, the site of the original parking lot, and acquired surrounding properties were earmarked to become part of the Disneyland Resort. At that time, the property saw the addition of the Disney California Adventure theme park, a shopping, dining and entertainment complex named Downtown Disney, a remodeled Disneyland Hotel, the construction of Disney's Grand Californian Hotel & Spa, and the acquisition and re-branding of the Pan Pacific Hotel as Disney's Paradise Pier Hotel. The park was renamed "Disneyland Park" to distinguish it from the larger complex under construction. Because the existing parking lot (south of Disneyland) was repurposed by these projects, the six-level, 10,250-space Mickey and Friends parking structure was constructed in the northwest corner. Upon completion in 2000, it was the largest parking structure in the United States.[31]

The park's management team during the mid-1990s was a source of controversy among fans and employees. In an effort to boost profits, various changes were begun by then-executives Cynthia Harriss and Paul Pressler. While their initiatives provided a short-term increase in shareholder returns, they drew widespread criticism for their lack of foresight. The retail backgrounds of Harriss and Pressler led to a gradual shift in Disneyland's focus from attractions to merchandising. Outside consultants McKinsey & Company were brought in to help streamline operations, resulting in many changes and cutbacks. After nearly a decade of deferred maintenance, the original park was showing signs of neglect. Fans of the park decried the perceived decline in customer value and park quality and rallied for the dismissal of the management team.[32]

21st century

Matt Ouimet, the former president of the Disney Cruise Line, was promoted to assume leadership of the Disneyland Resort in late 2003. Shortly afterward, he selected Greg Emmer as Senior Vice President of Operations. Emmer was a long-time Disney cast member who had worked at Disneyland in his youth prior to moving to Florida and held multiple executive leadership positions at the Walt Disney World Resort. Ouimet quickly set about reversing certain trends, especially concerning cosmetic maintenance and a return to the original infrastructure maintenance schedule, in hopes of restoring Disneyland's former safety record. Similarly to Disney himself, Ouimet and Emmer could often be seen walking the park during business hours with members of their respective staff, wearing cast member name badges, standing in line for attractions, and welcoming guests' comments. In July 2006, Ouimet left The Walt Disney Company to become president of Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide. Soon after, Ed Grier, executive managing director of Walt Disney Attractions Japan, was named president of the resort. In October 2009, Grier announced his retirement, and was replaced by George Kalogridis.

The "Happiest Homecoming on Earth" was an eighteen-month-long celebration (held through 2005 and 2006) of the fiftieth anniversary of the Disneyland Park, also celebrating Disneyland's milestone throughout Disney parks worldwide. In 2004, the park underwent major renovations in preparation, restoring many attractions, notably Space Mountain, Jungle Cruise, the Haunted Mansion, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room. Attractions that had been in the park on opening day had one ride vehicle painted gold, and the park was decorated with fifty Golden Mickey Ears. The celebration started on May 5, 2005, and ended on September 30, 2006, and was followed by the "Year of a Million Dreams" celebration, lasting twenty-seven months and ending on December 31, 2008.

Beginning on January 1, 2010, Disney Parks hosted the Give a Day, Get a Disney Day volunteer program, in which Disney encouraged people to volunteer with a participating charity and receive a free Disney Day at either a Disneyland Resort or Walt Disney World park. On March 9, 2010, Disney announced that it had reached its goal of one million volunteers and ended the promotion to anyone who had not yet registered and signed up for a specific volunteer situation.

In July 2015, Disneyland celebrated its 60th Diamond Celebration anniversary.[33] Disneyland Park introduced the Paint the Night parade and Disneyland Forever fireworks show, and Sleeping Beauty Castle is decorated in diamonds with a large "60" logo. The Diamond Celebration concluded in September 2016 and the whole decoration of the anniversary was removed around Halloween 2016.

Disneyland, along with Disney California Adventure, was closed indefinitely starting March 14, 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic.[34][35]

Lands

Disneyland Park consists of nine themed "lands" and a number of concealed backstage areas, and occupies over 100 acres (40 ha) with the new addition of Mickey and Minnie's Runaway Railway that's coming to Mickeys Toontown in 2022.[16] The park opened with Main Street, U.S.A., Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland, and has since added New Orleans Square in 1966, Bear Country (now known as Critter Country) in 1972, and Mickey's Toontown in 1993, and Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge in 2019.[36] In 1957, Holidayland opened to the public with a nine-acre (3.6 ha) recreation area including a circus and baseball diamond, but was closed in late 1961. It is often referred to as the "lost" land of Disneyland. Throughout the park are "Hidden Mickeys", representations of Mickey Mouse heads inserted subtly into the design of attractions and environmental decor. An elevated berm supports the 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge Disneyland Railroad that circumnavigates the park.

- Lands of Disneyland

Main Street, U.S.A.

Main Street, U.S.A.

(2010)- Adventureland

(Themed for a 1950s view of adventure, capitalizing on the post-war Tiki craze) - Frontierland

(Big Thunder Mountain Railroad in 2008) .jpg) New Orleans Square

New Orleans Square

(The Haunted Mansion and Fantasmic! viewing area in 2010)- Critter Country

(Splash Mountain in 2010)  Fantasyland

Fantasyland

(Peter Pan's Flight and the Matterhorn Bobsleds) Mickey's Toontown

Mickey's Toontown

(2010) Tomorrowland

Tomorrowland

(Space Mountain in 2010) Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge

Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge

(2019)

Main Street, U.S.A.

Main Street, U.S.A. is patterned after a typical Midwest town of the early 20th century. Main Street, U.S.A. has a train station, town square, movie theater, city hall, firehouse with a steam-powered pump engine, emporium, shops, arcades, double-decker bus, horse-drawn streetcar, and jitneys. Main Street is also home to the Disney Art Gallery and the Opera House which showcases Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, a show featuring an Audio-Animatronic version of the president. At the far end of Main Street, U.S.A. is Sleeping Beauty Castle, the Partners statue, and the Central Plaza (also known as the Hub), which is a portal to most of the themed lands: the entrance to Fantasyland is by way of a drawbridge across a moat and through the castle. Adventureland, Frontierland, and Tomorrowland are on both sides of the castle. Several lands are not directly connected to the Central Plaza—namely, New Orleans Square, Critter Country and Mickey's Toontown.

The design of Main Street, U.S.A. uses the technique of forced perspective to create an illusion of height. Buildings along Main Street are built at 3⁄4 scale on the first level, then 5⁄8 on the second story, and 1⁄2 scale on the third—reducing the scale by 1⁄8 each level up.

Adventureland

Adventureland is designed to recreate the feel of an exotic tropical place in a far-off region of the world. "To create a land that would make this dream reality", said Walt Disney, "we pictured ourselves far from civilization, in the remote jungles of Asia and Africa." Attractions include opening day's Jungle Cruise, the Indiana Jones Adventure, and Tarzan's Treehouse, which is a conversion of Swiss Family Treehouse from the Walt Disney film Swiss Family Robinson. Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room which is located at the entrance to Adventureland was the first feature attraction to employ Audio-Animatronics, a computer synchronization of sound and robotics.

New Orleans Square

New Orleans Square is based on 19th-century New Orleans, opened on July 24, 1966. It is home to Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion, with nighttime entertainment in Fantasmic!. This area is the home of Club 33.

Frontierland

Frontierland recreates the setting of pioneer days along the American frontier. According to Walt Disney, "All of us have cause to be proud of our country's history, shaped by the pioneering spirit of our forefathers. Our adventures are designed to give you the feeling of having lived, even for a short while, during our country's pioneer days." Frontierland is home to the Pinewood Indians band of animatronic Native Americans, who live on the banks of the Rivers of America. Entertainment and attractions include Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, the Mark Twain Riverboat, the Sailing Ship Columbia, Pirate's Lair on Tom Sawyer Island, and Frontierland Shootin' Exposition. Frontierland is also home to the Golden Horseshoe Saloon, an Old West-style show palace.

Critter Country

Critter Country opened in 1972 as "Bear Country", and was renamed in 1988. Formerly the area was home to Indian Village, where indigenous tribespeople demonstrated their dances and other customs. Today, the main draw of the area is Splash Mountain, a log-flume journey inspired by the Uncle Remus stories of Joel Chandler Harris and the animated segments of Disney's Academy Award-winning 1946 film Song of the South. In 2003, a dark ride called The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh replaced the Country Bear Jamboree, which closed in 2001. Country Bear Jamboree is still open in Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom.

Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge

Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge is set within the Star Wars universe, in the Black Spire Outpost village on the remote frontier planet of Batuu. Attractions include the Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run and Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance.[37] The land opened in 2019, replacing Big Thunder Ranch and former backstage areas.[38][39]

Fantasyland

Fantasyland is the area of Disneyland of which Walt Disney said, "What youngster has not dreamed of flying with Peter Pan over moonlit London, or tumbling into Alice's nonsensical Wonderland? In Fantasyland, these classic stories of everyone's youth have become realities for youngsters – of all ages – to participate in." Fantasyland was originally styled in a medieval European fairground fashion, but its 1983 refurbishment turned it into a Bavarian village. Attractions include several dark rides, the King Arthur Carrousel, and various family attractions. Fantasyland has the most fiber optics in the park; more than half of them are in Peter Pan's Flight.[40] Sleeping Beauty's Castle features a walk-through story telling of Briar Rose's adventure as Sleeping Beauty. The attraction opened in 1959, was redesigned in 1972, closed in 1992 for reasons of security and the new installation of pneumatic ram firework shell mortars for "Believe, There's Magic in the Stars", and reopened 2008 with new renditions and methods of storytelling and the restored work of Eyvind Earle.

Mickey's Toontown

Mickey's Toontown opened in 1993 and was partly inspired by the fictional Los Angeles suburb of Toontown in the Touchstone Pictures 1988 release Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Mickey's Toontown is based on a 1930s cartoon aesthetic and is home to Disney's most popular cartoon characters. Toontown features two main attractions: Gadget's Go Coaster and Roger Rabbit's Car Toon Spin. The "city" is also home to cartoon character's houses such as the house of Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse and Goofy, as well as Donald Duck's boat. The 3 ft (914 mm) gauge Jolly Trolley can also be found in this area, though it closed as an attraction in 2003 and is now present only for display purposes. In 2022 Mickey & Minnie's Runaway Railway will open at Mickey's Toontown. The new family friendly dark ride will increase the size of Toontown as well as the size of Disneyland from 99 to 101 acres (40 to 41 ha).

Tomorrowland

During the 1955 inauguration Walt Disney dedicated Tomorrowland with these words: "Tomorrow can be a wonderful age. Our scientists today are opening the doors of the Space Age to achievements that will benefit our children and generations to come. The Tomorrowland attractions have been designed to give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future."

Disneyland producer Ward Kimball had rocket scientists Wernher von Braun, Willy Ley, and Heinz Haber serve as technical consultants during the original design of Tomorrowland.[41] Initial attractions included Rocket to the Moon, Astro-Jets and Autopia; later, the first incarnation of the Submarine Voyage was added. The area underwent a major transformation in 1967 to become New Tomorrowland, and then again in 1998 when its focus was changed to present a "retro-future" theme reminiscent of the illustrations of Jules Verne.

Current attractions include Space Mountain, Star Wars Launch Bay, Autopia, Jedi Training: Trials of the Temple, the Disneyland Monorail Tomorrowland Station, Astro Orbitor, and Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters. Finding Nemo Submarine Voyage opened on June 11, 2007, resurrecting the original Submarine Voyage which closed in 1998. Star Tours was closed in July 2010 and replaced with Star Tours–The Adventures Continue in June 2011.

Operations

Backstage

Major buildings backstage include the Frank Gehry-designed Team Disney Anaheim,[42] where most of the division's administration currently works, as well as the Old Administration Building, behind Tomorrowland.

Photography is forbidden in these areas, both inside and outside, although some photos have found their way to a variety of web sites. Guests who attempt to explore backstage are warned and often escorted from the property.[43]

Transportation

Walt Disney had a longtime interest in transportation, and trains in particular. Disney's passion for the "iron horse" led to him building a miniature live steam backyard railroad—the "Carolwood Pacific Railroad"—on the grounds of his Holmby Hills estate. Throughout all the iterations of Disneyland during the 17 or so years when Disney was conceiving it, one element remained constant: a train encircling the park.[10] The primary designer for the park transportation vehicles was Bob Gurr who gave himself the title of Director of Special Vehicle Design in 1954.[44]

Encircling Disneyland and providing a grand circle tour is the Disneyland Railroad (DRR), a 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge short-line railway consisting of five oil-fired and steam-powered locomotives, in addition to three passenger trains and one passenger-carrying freight train. Originally known as the Disneyland and Santa Fe Railroad, the DRR was presented by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway until 1974. From 1955 to 1974, the Santa Fe Rail Pass was accepted in lieu of a Disneyland "D" coupon. With a 3 ft (914 mm) gauge, the most common narrow track gauge used in North America, the track runs in a continuous loop around Disneyland through each of its realms. Each 1900s-era train departs Main Street Station on an excursion that includes scheduled station stops at: New Orleans Square Station; Toontown Depot; and Tomorrowland Station. The Grand Circle Tour then concludes with a visit to the "Grand Canyon/Primeval World" dioramas before returning passengers to Main Street, U.S.A.[45]

One of Disneyland's signature attractions is its Disneyland Monorail System monorail service, which opened in Tomorrowland in 1959 as the first daily-operating monorail train system in the Western Hemisphere. The monorail guideway has remained almost exactly the same since 1961, aside from small alterations while Indiana Jones Adventure was being built. Five generations of monorail trains have been used in the park, since their lightweight construction means they wear out quickly. The most recent operating generation, the Mark VII, was installed in 2008. The monorail shuttles visitors between two stations, one inside the park in Tomorrowland and one in Downtown Disney. It follows a 2.5-mile-long (4.0 km) route designed to show the park from above. Currently, the Mark VII is running with the colors red, blue and orange. The monorail was originally a loop built with just one station in Tomorrowland. Its track was extended and a second station opened at the Disneyland Hotel in 1961. With the creation of Downtown Disney in 2001, the new destination is Downtown Disney, instead of the Disneyland Hotel. The physical location of the monorail station did not change, but the original station building was demolished as part of the hotel downsizing, and the new station is now separated from the hotel by several Downtown Disney buildings, including ESPN Zone and the Rainforest Café.[46]

All of the vehicles found on Main Street, U.S.A., grouped together as the Main Street Vehicles attraction, were designed to accurately reflect turn-of-the-century vehicles, including a 3 ft (914 mm) gauge[47] tramway featuring horse-drawn streetcars, a double-decker bus, a fire engine, and an automobile.[48] They are available for one-way rides along Main Street, U.S.A. The horse-drawn streetcars are also used by the park entertainment, including The Dapper Dans. The horseless carriages are modeled after cars built in 1903, and are two-cylinder, four-horsepower (3 kW) engines with manual transmission and steering. Walt Disney used to drive the fire engine around the park before it opened, and it has been used to host celebrity guests and in the parades. Most of the original main street vehicles were designed by Bob Gurr.

From the late 1950s to 1968, Los Angeles Airways provided regularly scheduled helicopter passenger service between Disneyland and Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and other cities in the area. The helicopters initially operated from Anaheim/Disneyland Heliport, located behind Tomorrowland. Service later moved, in 1960, to a new heliport north of the Disneyland Hotel.[49] Arriving guests were transported to the Disneyland Hotel via tram. The service ended after two fatal crashes in 1968: The crash in Paramount, California, on May 22, 1968, killed 23 (the worst helicopter accident in aviation history at that time). The second crash in Compton, California on August 14, 1968, killed 21.[50]

Live entertainment

In addition to the attractions, Disneyland provides live entertainment throughout the park. Most of the mentioned entertainment is not offered daily, but only on selected days of the week, or selected periods of the year.

Many Disney characters can be found throughout the park, greeting visitors, interacting with children, and posing for photos. Some characters have specific areas where they are scheduled to appear, but can be found wandering as well. Some of the rarest are characters like Rabbit (from Winnie-the-Pooh), Max, Mushu, and Agent P.[51] Periodically through recent decades (and most recently during the summers of 2005 and 2006), Mickey Mouse would climb the Matterhorn attraction several times a day with the support of Minnie, Goofy, and other performers. Other mountain climbers could also be seen on the Matterhorn from time to time. As of March 2007, Mickey and his "toon" friends no longer climb the Matterhorn but the climbing program continues. Every evening at dusk, there is a military-style flag retreat to lower the U.S. Flag by a ceremonial detail of Disneyland's Security staff. The ceremony is usually held between 4:00 and 5:00 pm, depending on the entertainment being offered on Main Street, U.S.A., to prevent conflicts with crowds and music. Disney does report the time the Flag Retreat is scheduled on its Times Guide, offered at the entrance turnstiles and other locations. The Disneyland Band, which has been part of the park since its opening, plays the role of the Town Band on Main Street, U.S.A. It also breaks out into smaller groups like the Main Street Strawhatters, the Hook and Ladder Co., and the Pearly Band in Fantasyland. However, on March 31, 2015, the Disneyland Resort notified the band members of an "end of run". The reason for doing so is that they would start a new higher energy band. The veteran band members were invited to audition for the new Disneyland band, and were told that even if they did not make the new band or audition, they would still play in small groups around the park. This sparked some controversy with supporters of the traditional band.[52]

Parades

Disneyland has featured a number of different parades traveling down the park's central Main Street – Fantasyland corridor. There have been daytime and nighttime parades that celebrated Disney films or seasonal holidays with characters, music, and large floats. One of the most popular parades was the Main Street Electrical Parade, which recently ended a limited-time return engagement after an extended run at the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. From May 5, 2005 through November 7, 2008, as part of Disneyland's 50th anniversary, Walt Disney's Parade of Dreams was presented, celebrating several Disney films including The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, Alice in Wonderland, and Pinocchio. In 2009, Walt Disney's Parade of Dreams was replaced by Celebrate! A Street Party, which premiered on March 27, 2009. Disney did not call Celebrate! A Street Party a parade, but rather a "street event." During the Christmas season, Disneyland presents "A Christmas Fantasy" Parade. Walt Disney's Parade of Dreams was replaced by Mickey's Soundsational Parade, which debuted on May 27, 2011.[53] Disneyland debuted a new nighttime parade called "Paint the Night", on May 22, 2015, as part of the park's 60th anniversary.[54]

Fireworks shows

Elaborate fireworks shows synchronized with Disney songs and often have appearances from Tinker Bell (and other characters) flying in the sky above Sleeping Beauty Castle. Since 2000, presentations have become more elaborate, featuring new pyrotechnics, launch techniques, and story lines. In 2004, Disneyland introduced a new air launch pyrotechnics system, reducing ground level smoke and noise and decreasing negative environmental impacts. At the time the technology debuted, Disney announced it would donate the patents to a non-profit organization for use throughout the industry.[55] Projection mapping technology debuted on It's a Small World with the creation of The Magic, the Memories and You in 2011, and expanded to Main Street and Sleeping Beauty Castle in 2015 with the premiere of Disneyland Forever.

- Regular fireworks shows:

- 1958–1999 & 2015: Fantasy in the Sky

- 2000–2004: Believe... There's Magic in the Stars

- 2004–2005: Imagine... A Fantasy in the Sky

- 2005–2014; 2017–2019: Remember... Dreams Come True

- 2009–2014 (summer): Magical: Disney's New Nighttime Spectacular of Magical Celebrations

- 2019 (summer): Disneyland Forever

- Seasonal fireworks shows:

- September–October Halloween Screams

- Independence Day Week: Disney's Celebrate America: A 4th of July Concert in the Sky

- November–January: Believe... In Holiday Magic

- Limited edition fireworks shows

- 60th Anniversary: Disneyland Forever

- Pixar Fest: Together Forever

- Get Your Ears On – A Mickey and Minnie Celebration: Mickey's Mix Magic

Since 2009, Disneyland has moved to a rotating repertoire of firework spectaculars.

Scheduling of fireworks shows depends on the time of year. During the slower off-season periods, the fireworks are only offered on weekends. During the busier times, Disney offers additional nights. The park offers fireworks nightly during its busy periods, which include Easter/Spring Break, Summer and Christmas time. Disneyland spends about $41,000 per night on the fireworks show. The show is normally offered at 8:45 or 9:30 pm if the park is scheduled to close at 10 pm or later, but shows have started as early as 5:45 pm. A major consideration is weather/winds, especially at higher elevations, which can, and often will, force the delay or cancellation of the show. In response to this, alternate versions of the fireworks spectaculars have been created in recent years, solely using the projections and lighting effects. With a few minor exceptions, such as July 4 and New Year's Eve, shows must finish by 10:00 pm due to the conditions of the permit issued by the City of Anaheim.

In recent years, Disneyland uses smaller and mid-sized fireworks shells and more low-level pyrotechnics on the castle to allow guests to enjoy the fireworks spectaculars even if there is a weather issue such as high wind. This precedent is known as B-show. The first fireworks show to have this format was Believe... In Holiday Magic from the 2018 holiday season.

Attendance

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tickets

From Disneyland's opening day until 1982, the price of the attractions was in addition to the price of park admission.[68] Guests paid a small admission fee to get into the park, but admission to most of the rides and attractions required guests to purchase tickets, either individually or in a book, that consisted of several coupons, initially labeled "A" through "C". "A" coupons allowed admission to the smaller rides and attractions such as the Main Street Vehicles, whereas "C" coupons were used for the most common attractions like Peter Pan's Flight, or the Mad Tea Party. As more thrilling rides were introduced, such as the Disneyland Monorail or the Matterhorn Bobsleds, "D" and then eventually "E" coupons were introduced. Coupons could be combined to equal the equivalent of another ticket (e.g., two "A" tickets equal one "B" ticket).

Disneyland later featured a "Keys to the Kingdom" booklet of tickets, which consisted of 10 unvalued coupons sold for a single flat rate. These coupons could be used for any attraction regardless of its regular value.

In 1982, Disney dropped the idea for individual ride tickets to a single admission price with unlimited access to all attractions, "except shooting galleries".[69] While this idea was not original to Disney, it had business advantages: in addition to guaranteeing that everyone paid the same entry amount regardless of their length of stay or number of rides ridden, the park no longer had to print ride tickets, provide staff for ticket booths, nor provide staff to collect tickets or monitor attractions for people sneaking on without tickets. Later, Disney introduced other entry options such as multi-day passes, Annual Passes (which allow unlimited entry to the Park for an annual fee), and Southern California residents' discounts.

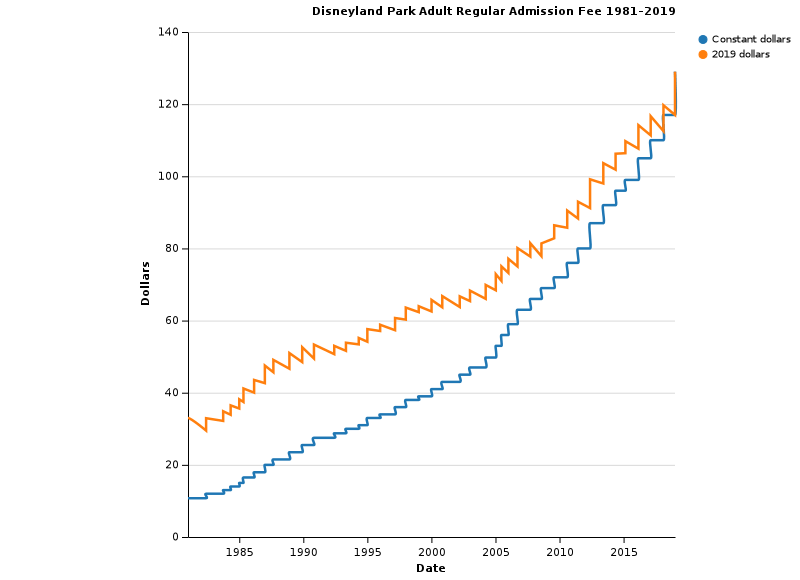

On February 28, 2016, Disneyland adopted a demand-based pricing system for single-day admission, charging different prices for "value", "regular", and "peak" days, based on projected attendance. Approximately 30% of days will be designated as "value", mainly weekdays when school is in session, 44% will be designated as "regular", and 26% will be designated as "peak", mostly during holidays and weekends in July.[70][71]

| Date | 1981* | June 1982 | October 1983 | May 1984 | January 1985 | May 1985 | March 1986 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price US$ | $10.75 | $12.00 | $13.00 | $14.00 | $15.00 | $16.50 | $17.95 | |||

| Date | January 1987 | September 1987 | December 1988 | December 1989 | November 1990 | June 1992 | May 1993 | |||

| Price US$ | $20.00 | $21.50 | $23.50 | $25.50 | $27.50 | $28.75 | $30.00 | |||

| Date | May 1994 | January 1995 | January 1996 | March 1997 | January 1998 | January 5, 1999 | January 5, 2000 | |||

| Price US$ | $31.00 | $33.00 | $34.00 | $36.00 | $38.00 | $39.00 | $41.00 | |||

| Date | November 6, 2000 | March 19, 2002 | January 6, 2003 | March 28, 2004 | January 10, 2005 | June 20, 2005 | January 4, 2006 | |||

| Price US$ | $43.00 | $45.00 | $47.00 | $49.75 | $53.00 | $56.00 | $59.00 | |||

| Date | September 20, 2006 | September 21, 2007 | August 3, 2008 | August 2, 2009 | August 8, 2010 | June 12, 2011 | May 20, 2012 | |||

| Price US$ | $63.00 | $66.00 | $69.00 | $72.00 | $76.00 | $80.00 | $87.00 | |||

| Date | June 18, 2013 | May 18, 2014 | February 22, 2015 | February 28, 2016 | February 12, 2017 | February 11, 2018 | January 6, 2019 | |||

| Price | $92.00 | $96.00 | $99.00 | $95/$105/$119 | $97/$110/$124 | $97/$117/$135 | $104/$129/$149 | |||

^* Before 1982, passport tickets were available to groups only.[75]

See or edit raw graph data.

Closures

Disneyland has had six unscheduled closures:

- In 1963, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[76]

- In 1970, due to an anti-Vietnam riot instigated by the Youth International Party.

- In 1987, on December 16 due to a winter storm.[77]

- In 1994, for inspection after the Northridge earthquake.

- In 2001, after the September 11 attacks.

- In 2020, in response to the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[35][78]

Additionally, Disneyland has had numerous planned closures:

- In the early years, the park was often scheduled to be closed on Mondays and Tuesdays during the off-season.[79] This was in conjunction with nearby Knott's Berry Farm, which closed on Wednesdays and Thursdays to keep costs down for both parks, while offering Orange County visitors a place to go 7 days a week.

- On May 4, 2005, for the 50th Anniversary Celebration media event.[80]

- The park has closed early to accommodate various special events, such as special press events, tour groups, VIP groups, and private parties. It is common for a corporation to rent the entire park for the evening. In such cases, special passes are issued which are valid for admission to all rides and attractions. At the ticket booths and on published schedules, regular guests are notified of the early closures. In the late afternoon, cast members announce that the park is closing, then clear the park of everyone without the special passes.

Promotions

Every year in October, Disneyland has a Halloween promotion. During this promotion, or as Disneyland calls it a "party", areas in the park are decorated in a Halloween theme. Space Mountain and the Haunted Mansion are temporarily re-themed as part of the promotion. A Halloween party is offered on selected nights in late September and October for a separate fee, with a special fireworks show that is only shown at the party.

From early November until the beginning of January, the park is decorated for the holidays. Seasonal entertainment includes the Believe... In Holiday Magic firework show and A Christmas Fantasy Parade, while the Haunted Mansion and It's a Small World are temporarily redecorated in a holiday theme. The Sleeping Beauty Castle is also known to become snow-capped and decorated with colorful lights during the holidays as well.

See also

- List of Disney theme park attractions

- List of Disney attractions that were never built

- Incidents at Disneyland Resort

- Rail transport in Walt Disney Parks and Resorts

- Dapper Day

- C. V. Wood

- Theme parks that were closely themed to Disneyland

- Beijing Shijingshan Amusement Park – Mainland Chinese theme park

- Nara Dreamland – Now-defunct Japanese theme park

- Theme parks built by former Disneyland employee C. V. Wood

- Freedomland U.S.A.

- Heritage Square in Golden, Colorado

- Pleasure Island

References

Notes

- "Disneyland Celebrates 56 Years on July 17". Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Savvas, George (February 7, 2017). "Star Wars-Themed Lands at Disney Parks Set to Open in 2019". Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "TEA/AECOM 2018 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). May 23, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- "News from the Disney Board — March 04, 2005". The Walt Disney Company. March 4, 2005. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014.

- "Disneyland Resort Celebrates 60 Years of 'Sleeping Beauty'". Disney Parks Blog. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "Wave file of dedication speech". Archived from the original on December 20, 2005.

- Abrams, Nathan; Hughes, Julie (2000). Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in 50s America. A&C Black. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-902459-06-6.

- Krasniewicz, Louise (2010). Walt Disney: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-313-35830-2.

- Greenwood, Lee (May 2012). Does God Still Bless the USA?: A Plea for a Better America. Tate Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-61777-444-7.

- "Home". The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Siriano, Christopher (2007). The House of David. Arcadia Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7385-5082-4.

- "Walt's first vision of Disneyland". Walt's Apartment. August 31, 2012. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- "Walt Disney Visits Henry Ford's Greenfield Village". Greenfield Village. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- Walt Disney's Railroad Story. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-9758584-2-4.

- Kaufman, Richard. "Mouseplanet — Behind the Magic: 50 Years of Disneyland".

- "Disneyland History". JustDisney.com. July 21, 1954. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Price, Harrison "Buzz" (May 2004). "Walt's Revolution! By the Numbers". Stanford Business Magazine. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Stewart, James B. (2005). Disney War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80993-1.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 6, 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- "Disneyland: From orange groves to Magic Kingdom". Los Angeles Times. May 18, 2005. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009.

- "Disneyland Opening". JustDisney.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Korkis, Jim. "When Did Disneyland Open? July 17 or July 18?". MousePlanet.com. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Koening, David (2006). Mouse Tales: A Behind the Ears Look at Disneyland. Bona Venture Press. ISBN 0-9640605-6-6.

- "Disneyland Opening". JustDisney.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009.

- "Nikita Khrushchev Doesn't Go to Disneyland". Sean's Russia Blog. July 24, 2009. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009.

- "Disneyland In The Beginning: A Look Back". Boca Life Magazine. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Rich, Frank (December 26, 2010). "Who Killed the Disneyland Dream?". The New York Times. p. WK14. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017.

- Galber, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination. New York: Alfred A Knopf.

- Arellano, Gustavo (April 5, 2012). "How Doritos Were Born at Disneyland". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on April 9, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Kopetman, Roxana (December 6, 1985). "An Airy Birthday Salute to Disneyland". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- "The World's Largest Parking Lots". Forbes. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- Dickerson, Marla (September 12, 1996). "Self-Styled Keepers of the Magic Kingdom". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- "Disneyland Resort Diamond Celebration Continues Through September 5, 2016". Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Barnes, Brooks (March 12, 2020). "Disney Parks and Cruise Line Will Close in Response to Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Disneyland closes because of the coronavirus outbreak". CNN. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Vlessing, Etan; Parker, Ryan. "Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge Sets Opening Dates". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Star Wars-Themed Lands Coming to Walt Disney World and Disneyland Resorts". Disney Parks Blog. 2015. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- "It's official: 'Star Wars' theme land coming to Disneyland". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on August 16, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- Vlessing, Etan; Parker, Ryan (March 7, 2019). "Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge Sets Opening Dates". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- French, Sally (August 31, 2008). "Did you know? Fantasyland". Archived from the original on September 22, 2013.

- Wright, Mike (1993). "The Disney-Von Braun Collaboration and Its Influence on Space Exploration". NASA. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Team Disneyland Administration Building". Arcspace.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Grant, Matt (January 10, 2013). "Disney 'explorer' banned for life". Fort Myers/Naples, Florida: WFTX-TV. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Broggie, Michael (2006). Walt Disney's Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom (2nd ed.). The Donning Company Publishers. pp. 222, 251, 254, 294, 297–298. ISBN 1-57864-309-0.

- Broggie, Michael (2006). Walt Disney's Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom (2nd ed.). The Donning Company Publishers. pp. 215–282. ISBN 1-57864-309-0.

- Broggie, Michael (2006). Walt Disney's Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom (2nd ed.). The Donning Company Publishers. pp. 29, 200, 283, 283, 294, 297–305. ISBN 1-57864-309-0.

- "Trams of the World 2017" (PDF). Blickpunkt Straßenbahn. January 24, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Broggie, Michael (2006). Walt Disney's Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom (2nd ed.). The Donning Company Publishers. pp. 29, 229, 285–4. ISBN 1-57864-309-0.

- Freeman, Paul. "Disneyland Heliport, Anaheim, CA". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. Archived from the original on October 23, 2006.

- Tully, William; Larsen, Dave (August 15, 1968). "21 Aboard Killed as Copter Falls in Compton Park". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- "Welcome to Disney Characters Central". Disney Characters Central. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Eades, Mark (April 4, 2015). "Staffing changes coming to Disneyland Band, which worries musicians' union". OC Register. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- "From Under the Sea to Galaxies Far, Far Away...Opening Dates Are Set for a Soundsational Summer at Disneyland Resort". Disney Parks Blog. February 25, 2011. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Slater, Shawn (January 28, 2015). "'Paint the Night' Parade Starts May 22 as Part of the Disneyland Resort Diamond Celebration". Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- "Environmentality Press Releases". The Walt Disney Company. June 28, 2004. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007.

- "TEA/AECOM 2013 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- "TEA/AECOM 2014 Global Attractions Attendance Report Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Attendance of Disneyland Park 1955–1979". The Disney Blog. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007.

- "Attendance of Disneyland Park 1980". Archived from the original on July 8, 2008 – via islandnet.com.

- "Disneyland – still magic after all these years". The Lewiston Journal. March 13, 1984.

- "Attendance of Disneyland Park 1984–2005". scottware.com.au. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015.

- "2006 TEA/ERA Attendance Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2011.

- "2007 TEA/ERA Attendance Report" (PDF). November 9, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2009.

- "2008 TEA/ERA Attendance Report" (PDF). November 9, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2009.

- "TEA/AECOM 2016 Theme Index and Museum Index" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "TEA/AECOM 2017 Theme Index and Museum Index" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "TEA/AECOM 2018 Theme Index and Museum Index" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- Walt Disney Productions (1979). Disneyland: The First Quarter Century. OCLC 6064274.

- Pacific Ocean Park is credited as being the first amusement park to use this method; "Six Flags Timeline". Archived from the original on December 29, 2013 – via csus.edu.

- "Disney adopts demand pricing; ticket prices will rise most days". Los Angeles Times. February 27, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- Palmeri, Chris (February 27, 2016). "Disneyland to Cost Up to 20% More as Parks Match Price to Demand". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "Disneyland Ups Prices: Adults, $41; Kids, $31". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Martin, Hugo (February 11, 2018). "Disneyland resort raises prices as much as 18%". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Martin, Hugo (January 6, 2019). "Disneyland Resort tickets and parking prices are going up again, as much as 25%". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "Collection of tickets". FindDisney.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007.

1981–1994 data

- Verrier, Richard (September 21, 2001). "Security Becomes Major Theme at U.S. Amusement Parks". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2009.

- Morrison, Patt; Citron, Alan (December 16, 1987). "Howling Storm Hits Southland : Snow Falls From Malibu to Desert; 12 Feared Dead". Los Angeles Times.

- "Walt Disney World Resort will remain closed until further notice". WESH. March 27, 2020.

- "Disneyland History – Important Events in Disneyland history". About.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007.

- "50th Report". DizHub.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2006.

Further reading

- Bright, Randy (1987). Disneyland: Inside Story. Harry N Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-0811-5.

- Dunlop, Beth (1996). Building a Dream: The Art of Disney Architecture. Harry N. Abrams Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3142-7.

- France, Van Arsdale (1991). Window on Main Street. Stabur. ISBN 0-941613-17-8.

- Gordon, Bruce; Mumford, David (1995). Disneyland: The Nickel Tour. Camphor Tree Publishers. ISBN 0-9646059-0-2.

- Marling, Karal Ann, ed. (1997). Designing Disney's Theme Parks: The Architecture of Reassurance. Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-013639-9.

- Koenig, David (1994). Mouse Tales: A Behind-the-Ears Look at Disneyland. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 0-9640605-5-8.

- Koenig, David (1999). More Mouse Tales: A Closer Peek Backstage at Disneyland. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 0-9640605-7-4.

- Strodder, Chris (2008). The Disneyland Encyclopedia. Santa Monica Press. ISBN 978-1-59580-033-6.

External links

- Official website

- Disneyland at the Roller Coaster DataBase

- Opening Day at Disneyland: Photos from 1955