Common brushtail possum

The common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula, from the Greek for "furry tailed" and the Latin for "little fox", previously in the genus Phalangista[4]) is a nocturnal, semi-arboreal marsupial of the family Phalangeridae, native to Australia, and the second-largest of the possums.

| Common brushtail possum[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Austins Ferry, Tasmania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Phalangeridae |

| Genus: | Trichosurus |

| Species: | T. vulpecula |

| Binomial name | |

| Trichosurus vulpecula (Kerr, 1792)[3] | |

| Subspecies | |

|

T. v. vulpecula | |

| |

| Common brushtail possum range | |

Like most possums, the common brushtail possum is nocturnal. It is mainly a folivore, but has been known to eat small mammals such as rats. In most Australian habitats, leaves of eucalyptus are a significant part of the diet, but rarely the sole item eaten. The tail is prehensile and naked on its lower underside. The four colour variations are silver-grey, brown, black, and gold.[5]

It is the Australian marsupial most often seen by city dwellers, as it is one of few that thrive in cities and a wide range of natural and human-modified environments. Around human habitations, common brushtails are inventive and determined foragers with a liking for fruit trees, vegetable gardens, and kitchen raids.

The common brushtail possum was introduced to New Zealand in the 1850s to establish a fur industry, but in the mild subtropical climate of New Zealand, and with few to no natural predators, it thrived to the extent that it became a major agricultural and conservation pest.

Description

The common brushtail possum has large and pointed ears. Its bushy tail (hence its name) is adapted to grasping branches, prehensile at the end with a hairless ventral patch.[6][7] Its fore feet have sharp claws and the first toe of each hind foot is clawless, but has a strong grasp.[7] The possum grooms itself with the third and fourth toes which are fused together.[7] It has a thick and woolly pelage that varies in colour depending on the subspecies. Colour patterns tend to be silver-grey, brown, black, red, or cream. The ventral areas are typically lighter and the tail is usually brown or black.[6][7] The muzzle is marked with dark patches.

The common brushtail possum has a head and body length of 32–58 cm[6] with a tail length of 24–40 cm.[7] It weighs 1.2-4.5 kg.[7] Males are generally larger than females. In addition, the coat of the male tends to be reddish at the shoulders. As with most marsupials, the female brushtail possum has a forward-opening, well-developed pouch.[6] The chest of both sexes has a scent gland that emits a reddish secretion which stains that fur around it. It marks its territory with these secretions.[8]

Biology and ecology

Range and habitat

.jpg)

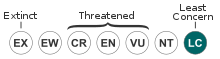

The common brushtail possum is perhaps the most widespread marsupial of Australia. It is found throughout the eastern and northern parts of the continent, as well as some western regions,[9] Tasmania[10] and a number of offshore islands, such as Kangaroo Island[11] and Barrow Island.[12][13] It is also widespread in New Zealand since its introduction in 1850. The common brushtail possum can be found in a variety of habitats, such as forests, semi-arid areas and even cultivated or urban areas.[6][7] It is mostly a forest inhabiting species, however it is also found in treeless areas.[7] In New Zealand, possums favour broadleaf-podocarp near farmland pastures.[14] In southern beech forests and pine plantations, possums are less common.[14] Overall, brushtail possums are more densely populated in New Zealand than in their native Australia.[15] This may be because Australia has more fragmented eucalypt forests and more predators. In Australia, brushtail possums are threatened by humans, tiger quolls, dogs, foxes, cats, goannas, carpet snakes, and powerful owls. In New Zealand, brushtail possums are threatened only by humans and cats.[15] The IUCN highlight the population trend in Australia as decreasing.

Food and foraging

The common brushtail possum can adapt to numerous kinds of vegetation.[15] It prefers Eucalyptus leaves, but also eats flowers, shoots, fruits, and seeds.[15] It may also consume animal matter such as insects, birds' eggs and chicks, and other small vertebrates.[16] Brushtail possums may eat three or four different plant species during a foraging trip, unlike some other arboreal marsupials, such as the koala and the greater glider, which focus on single species. The brushtail possum's rounded molars cannot cut Eucalyptus leaves as finely as more specialised feeders. They are more adapted to crushing their food, which enables them to chew fruit or herbs more effectively. The brushtail possums' caecum lacks internal ridges and cannot separate coarse and fine particles as efficiently as some other arboreal marsupials.[15] The brushtail possum cannot rely on Eucalyptus alone to provide sufficient protein.[17] Its more generalised and mixed diet, however, does provide adequate nitrogen.[18]

Behaviour

The common brushtail possum is largely arboreal and nocturnal. It has a mostly solitary lifestyle, and individuals keep their distance with scent markings (urinating) and vocalisations. They usually make their dens in natural places such as tree hollows and caves, but also use spaces in the roofs of houses. While they sometimes share dens, brushtails normally sleep in separate dens. Individuals from New Zealand use many more den sites than those from Australia.[19] Brushtail possums compete with each other and other animals for den spaces, and this contributes to their mortality. This is likely another reason why brushtail possum population densities are smaller in Australia than in New Zealand.[15] Brushtail possums are usually not aggressive towards each other and usually just stare with erect ears.[15] They vocalise with clicks, grunts, hisses, alarm chatters, guttural coughs, and screeching.[6][7]

Reproduction and life history

The common brushtail possum can breed at any time of the year, but breeding tends to peak in spring, from September to November, and in autumn, from March to May, in some areas. Mating is promiscuous and random; some males can sire several young in a season, while over half sire none.[15] In one Queensland population, males apparently need a month of consorting with females before they can mate with them.[20] Females have a gestation period of 16–18 days, after which they give birth to single young.[6][7] A newborn brushtail possum is only 1.5 cm long and weighs only 2 g. As usual for marsupials, the newborn may climb, unaided, through the female's fur and into the pouch and attach to a teat. The young develops and remains inside the mother's pouch for another 4-5 months. When older, the young is left in the den or rides on its mother's back until it is 7-9 months old.[6][7] Females reach sexual maturity when they are a year old, and males do so at the end of their second year.[6][7] Female young have a higher survival rate than their male counterparts due to establishing their home ranges closer to their mothers, while males travel farther in search of new nesting sites, encountering established territories from which they may be forcibly ejected. In the Orongorongo population, female young have been found to continue to associate with their mothers after weaning, and some inherit the prime den sites.[21] A possible competition exists between mothers and daughters for dens, and daughters may be excluded from a den occupied by the mother.[22] In forests with shortages of den sites, females apparently produce more sons, which do not compete directly for den sites, while in forests with plentiful den sites, female young are greater in number.[22] Brushtail possums can live up to 13 years in the wild.[6][7]

Relationship with humans

The common brushtail possum is considered a pest in some areas, as it is known to cause damage to pine plantations, regenerative forest, flowers, fruit trees, and buildings. Like other possums, it is rather tolerant of humans and can sometimes be hand fed, although it is not encouraged, as their claws are quite sharp and can cause infection or disease to humans if scratched. It is a traditional food source for some indigenous Australians.

Australia

Its fur has been considered valuable and has been harvested. Although once hunted extensively for its fur in Australia, the common brushtail possum is now protected in mainland states, but it has only been partially protected in Tasmania, where an annual hunting season is used. In addition, Tasmania gives crop-protection permits to landowners whose property has been damaged.[8]

While its populations are declining in some regions due to habitat loss, urban populations indicate an adaptation to the presence of humans.[23] In the mainland states, possum trapping is legal when attempting to evict possums from human residences (e.g. roofs), but possums must be released after dusk within 24 hours of capture, no more than 50 m from the trapping site. In some states, e.g. Victoria, trapped possums may be taken to registered veterinarians for euthanasia.[24] In South Australia, they are fully protected and permits are required for trapping possums in human residences[25] or for keeping or rescuing sick or injured wild possums and other native animals.[26]

New Zealand

Since its introduction from Australia by European settlers in the 1850s, the common brushtail possum has become a major threat to New Zealand native forests and birds. It is also a host for the highly contagious bovine tuberculosis.[8] (This is not an issue in Australia, where the disease has been eradicated).[27]

By the 1980s, the peak population had reached an estimated 60-70 million, but is now down to an estimated 30 million due to control measures. The New Zealand Department of Conservation controls possum numbers in many areas via the aerial dropping of 1080-laced bait.[28] Hunting is not restricted, but the population seems to be stable despite the annual killing thousands of the animals.[8]

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Morris, K.; Woinarski, J.; Friend, T.; Foulkes, J.; Kerle, A. & Ellis, M. (2008). "Trichosurus vulpecula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linné, Carl von; Archer, J.; Gmelin, Johann Friedrich; Kerr, Robert (1792). The animal kingdom, or zoological system, of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnæus. containing a complete systematic description, arrangement, and nomenclature, of all the known species and varieties of the mammalia, or animals which give suck to their young. 1. Printed for A. Strahan, and T. Cadell, London, and W. Creech, Edinburgh.

- "Define Phalangista vulpina - Source: '*'". www.hydroponicsearch.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- "Brushtail Possum". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- Nowak, R.M. (1991) Walker’s Mammals of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

- Cronin, L. (2008) Cronin’s Key Guide Australian Mammals. Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

- Meyer, Grace (2000). "Trichosurus vulpecula (silver-gray brushtail possum)". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Living with possums" (PDF). Department of Conservation and Land Management. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "Brushtail Possum". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tasmania). Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "Living with Possums in South Australia" (PDF). Department for Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "A Guide to the Mammals of Barrow Island" (PDF). Chevron Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-19. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "Tagged Barrow Island possums perish on mainland". Perth Now. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Efford MG (2000) "Possum density, population structure, and dynamics". In: The Brushtail Possum. TL Montague. (ed) Chapter 5, pp. 47-66. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln New Zealand.

- H Tyndale-Biscoe. (2005) Life of Marsupials. pp. 250-58. CSIRO Publishing.

- "Trichosurus vulpecula — Common Brush-tailed Possum". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Wellard GA, Hume ID (1981) "Nitrogen metabolism and nitrogen requirement of the brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula (Kerr)." Australian Journal of Zoology 29:147-57.

- Harris PM, Dellow DW, Broadhurst RB, (1985) "Protein and energy requirement and deposition in the growing brushtail possum and rex rabbit". Australian Journal of Zoology 33:425-36.

- Green WQ (1984) "A review of ecological studies relevant to management of the common brushtail possum". In Possums and Gliders. AP Smith, ID Hume pp 483-99. New South Wales: Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Limited.

- Winter JW (1976) The behaviour and social organisation of the brush-tail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula, Kerr) PhD Thesis, University of Queensland.

- Brockie R. (1992) A Living New Zealand Forest. Pp. 172. Dave Bateman Auckland.

- Johnson CN, Clinchy M, Taylor AC, Krebs CJ, Jarman PJ, Payne A, Ritchie EG. (2001) "Adjustment of offspring sex ratios in relation to the availability of resources for philopatric offspring in the common brushtail possum". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 268:2001-05.

- Roetman, P.E.J. & Daniels, C.B. (2009): The Possum-Tail Tree: Understanding Possums through Citizen Science. Barbara Hardy Centre for Sustainable Urban Environments, University of South Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-52199-2

- Department of Sustainability and Environment > Living with Possums in Victoria - Questions and Answers Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 July 2012.

- SA Department for Environment and Water > Plants and animals > Possums Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- SADepartment for Environment and Water > Possum Permits Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- More, SJ; Radunz, B; Glanville, RJ (5 September 2015). "Lessons learned during the successful eradication of bovine tuberculosis from Australia". The Veterinary Record. 177 (9): 224–32. doi:10.1136/vr.103163. PMC 4602242. PMID 26338937.

- Green, Wren. "The use of 1080 for pest control" (PDF). Animal Health Board and Department of Conservation. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

Further reading

- Marsh, K. J., Wallis, I. R., & Foley, W. J. (2003). The effect of inactivating tannins on the intake of Eucalyptus foliage by a specialist Eucalyptus folivore (Pseudocheirus peregrinus) and a generalist herbivore (Trichosurus vulpecula). Australian Journal of Zoology, 51, 41–42.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trichosurus vulpecula. |