Colossal squid

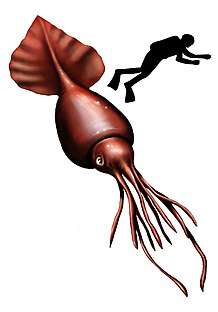

The colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) is part of the family Cranchiidae.[3] It is sometimes called the Antarctic squid or giant cranch squid and is believed to be the largest squid species in terms of mass.[4] It is the only recognized member of the genus Mesonychoteuthis and is known from only a small number of specimens.[5] The species is confirmed to reach a mass of at least 495 kilograms, though the largest specimens—known only from beaks found in sperm whale stomachs—may perhaps weigh as much as 600–700 kilograms (1,300–1,500 lb),[6][7] making it the largest-known invertebrate.[4] Maximum total length has been estimated at 9–10 meters (30–33 ft).[8]

| Colossal squid | |

|---|---|

| |

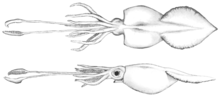

| Depiction with an inflated mantle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Superorder: | Decapodiformes |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Cranchiidae |

| Subfamily: | Taoniinae |

| Genus: | Mesonychoteuthis Robson, 1925 |

| Species: | M. hamiltoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni Robson, 1925[2] | |

| |

| Global range of M. hamiltoni | |

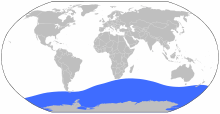

This species shares anatomy similar to other members of its family although it is the only member of the Cranchiidae family to display hooks on its arms and tentacles.[9][10] It is known to inhabit the circumantarctic Southern Ocean.[4] Although little is known about the behavior, it is known to use bioluminescence to attract prey.[11] Additionally, it is thought to be an ambush predator and is a major prey of the sperm whale.[12][13]

The first specimens were discovered and described in 1925.[14] It was not until 1981 that an whole adult specimen was discovered, and over another two decades passed after that for a second to be collected.[15][16] The largest colossal squid was caught in 2007, weighing 495 kg.[17] This specimen, along with a second colossal squid, is on display at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.[18][19]

Morphology

The colossal squid shares common features to all squids, such as a mantle for locomotion, one pair of gills, or certain external characteristics like eight arms and two tentacles, a head, and two fins.[9] In general, it is safe to describe the morphology and anatomy of the colossal squid the same way one would describe any other squid.[9] However, there are certain morphological/anatomical characteristics that separate the colossal squid from other squids in its family. Particularly, of the family Cranchiidae, the colossal squid is the only squid with hooks, swivelling or three-pointed, equipped on its arms and tentacles.[10] There are squids in other families that also have hooks, but no other squid in the Cranchiidae family uses hooks.[9]

In general, squids have a mantle length of about 300 mm and weigh about 0.1-0.2 kg.[9] However, the colossal squid is unlike most squid species, for it exhibits abyssal gigantism; it is the heaviest living invertebrate species, reaching weights up to 495 kg.[4] Compared to the giant squid, which also exhibits deep-sea gigantism, the colossal squid is shorter, but heavier.[4] Analysis of the beaks of other specimens from the stomach of sperm whales have shown that it is likely that colossal squids much heavier (up to 600 or 700 kg) exist.[6][7] The colossal squid also has the largest eyes documented in the animal kingdom.[20][21]

Distribution and habitat

The squid's known range extends thousands of kilometres north of Antarctica to southern South America, southern South Africa, and the southern tip of New Zealand, making it primarily an inhabitant of the entire circumantarctic Southern Ocean.[4] The region between the Weddell Sea and the wester Kerguelen archipelago has been deemed a “hotspot” based on characteristics of the habitat [22]. The squid’s vertical distribution appears to correlate directly with age. Young squid are found between 0-500m, adolescent squid are found 500-2,000m and adult squid are found primarily within the mesopelagic and bathypelagic regions of the open ocean [23].

Behavior

Feeding

Little is known about the behavior of this creature, but it is believed to feed on prey such as chaetognatha, large fish such as the Patagonian toothfish, and smaller squid in the deep ocean using bioluminescence.[11] A recent study by Remeslo, Yakushev and Laptikhovsky revealed that Antarctic toothfish make up a significant part of the colossal squid's diet; of the 8,000 toothfish brought aboard trawlers between 2011 and 2014, seventy-one showed clear signs of attack by colossal squid.[24] A study in Prydz Bay region of Antarctica found squid remains in a female colossal squid's stomach, suggesting the possibility of cannibalism within this species.[25]

Metabolism

The colossal squid is thought to have a very slow metabolic rate, needing only around 30 grams (1.1 oz) of prey daily for an adult with a mass of 500 kilograms (1,100 lb).[26] Estimates of its energy requirements suggest it is a slow-moving ambush predator, using its large eyes primarily for prey-detection rather than engaging in active hunting.[26][13]

Predation

Many sperm whales have scars on their backs, believed to be caused by the hooks of colossal squid. Colossal squid are a major prey item for sperm whales in the Antarctic; 14% of the squid beaks found in the stomachs of these sperm whales are those of the colossal squid, which indicates that colossal squid make up 77% of the biomass consumed by these whales.[27] Many other animals also feed on colossal squid, including beaked whales (such as the southern bottlenose whale), pilot whales, southern elephant seals, Patagonian toothfish, sleeper sharks (Somniosus antarcticus), and albatrosses (e.g., the wandering and sooty albatrosses).[4] However, beaks from mature adults have only been recovered from large predators (i.e. sperm whales and sleeper sharks), while the other predators only eat juveniles or young adults.[28]

Reproduction

Little is known about the colossal squid’s reproductive cycle although the colossal squid does have two distinct sexes. Many species of squid, however, develop gender-specific organs as they age and develop. [29]. The adult female colossal squid has been discovered in much shallower waters which likely implies that females spawn in shallower waters than their normal depth [30]. Additionally, the colossal squid has a high possible fecundity reaching over 4.2 million oocytes which is quite unique compared to other squids in such cold waters [31].

Vision

Unlike swordfish and other large pelagic species, the colossal squid (along with the giant squid) has eyes that are nearly 2-3 times the diameter of their deepsea counterparts. Further research suggests that colossal squid are able to see bioluminescence generated by large predators that disrupt plankton when they move. Additionally, this supports the idea that colossal squid are ambush predators [12].

Taxonomy and history

The colossal squid, species Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni was discovered in 1925.[14] This species belongs to the class Cephalopoda and family Cranchiidae.[3]

Most of the time, full colossal squid specimens are not collected; as of 2015, only 12 complete colossal squids had ever been recorded with only half of these being full adults.[5] Commonly, beak remnants of the colossal squid are collected. 55 beaks of colossal squids have been recorded in total.[5] Less commonly, 4 times, a fin, mantle, arm, or tentacle, of a colossal squid was collected.[5]

Notable discoveries

First specimens

The species was first discovered in the form of two arm crowns found in the stomach of a sperm whale in the winter of 1924-1925.[14] This species, then named Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, was formally described by Guy Coburn Robson 1925.[14]

Entire specimens

In 1981, a Russian trawler in the Ross Sea, off the coast of Antarctica, caught a large squid with a total length of over 4 m (13 ft), which was later identified as an immature female of M. hamiltoni.[15] This is a significant discovery for it would not be until 2003, that another full individual was discovered. In 2003, a complete specimen of a subadult female was found near the surface with a total length of 6 m (20 ft) and a mantle length of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in).[16] In 2005, the first full alive specimen was captured at a depth of 1,625 m (5,331 ft) while taking a toothfish from a longline off South Georgia Island.[32] Although the mantle was not brought aboard, its length was estimated at over 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in), and the tentacles measured 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in).[32] The animal is thought to have weighed between 150 and 200 kg (330 and 440 lb).[32]

Largest known specimen

The largest recorded specimen was a female, which are thought to be larger than males, captured in February of 2007 by a New Zealand fishing boat in the Ross Sea off of Antarctica.[21] The squid was close to dead when it was captured and subsequently was taken back to New Zealand for scientific study.[33] The specimen was initially estimated to measure about 10 meters in total length and weigh about 450 kg.[33] The squid turned out to actually weigh 495 kg.[17]

Defrosting and dissection, April–May 2008

Thawing and dissection of the specimen took place at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.[34] AUT biologist Steve O'Shea, Tsunemi Kubodera, and AUT biologist Kat Bolstad were invited to the museum to aid in the process.[34] Media reports suggested scientists at the museum were considering using a giant microwave to defrost the squid because thawing it at room temperature would take several days and it would likely begin to decompose on the outside while the core remained frozen.[35] However, they later opted for the more conventional approach of thawing the specimen in a bath of salt water.[36] After thawing, it was found that the specimen was 495 kg only 2.5 m, probably because the tentacles shrunk once the squid was dead.[17]

Parts of the specimen have been examined:

- The beak is considerably smaller than some found in the stomachs of sperm whales,[37][38] suggesting other colossal squid are much larger than this one.[37][38]

- The eye is 27 cm (11 in) wide, with a lens 12 cm (4.7 in) across. This is the largest eye of any known animal.[20] These measurements are of the partly collapsed specimen; alive, the eye was probably 30[21] to 40 cm (12 to 16 in) across.[39]

- Inspection of the specimen with an endoscope revealed ovaries containing thousands of eggs.[21]

Exhibition

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa began displaying this specimen in an exhibition that opened on December 13, 2008; however the exhibition was closed in 2018 and slated to return in 2019.[18]

Conservation status and human interactions

The colossal squid has been assessed as least concern on the IUCN Red List. Furthermore, colossal squid are not targeted by fishermen; rather, they are only caught when they attempt to feed on fish caught on hooks.[41] Additionally, due to their habitat, interactions between humans and colossal squid are considered rare.[42]

See also

- Gigantic octopus

- Kraken

- Giant squid

References

- Barratt, I.; Allcock, L. (2014). "Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T163170A980001. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T163170A980001.en. Downloaded on 01 March 2018.

- Julian Finn (2016). "Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni Robson, 1925". World Register of Marine Species. Flanders Marine Institute. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "ITIS Report".

- Rosa, Rui & Lopes, Vanessa M. & Guerreiro, Miguel & Bolstad, Kathrin & Xavier, José C. 2017. Biology and ecology of the world's largest invertebrate, the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni): a short review. Polar Biology, published online on March 30, 2017. doi:10.1007/s00300-017-2104-5

- McClain CR, Balk MA, Benfield MC, Branch TA, Chen C, Cosgrove J, Dove ADM, Gaskins LC, Helm RR, Hochberg FG, Lee FB, Marshall A, McMurray SE, Schanche C, Stone SN, Thaler AD. 2015. Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3:e715 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.715

- [Te Papa] (2019). How big is the colossal squid on display? Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

- [Te Papa] (2019). The beak of the colossal squid. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

- Roper, C.F.E. & P. Jereb (2010). Family Cranchiidae. In: P. Jereb & C.F.E. Roper (eds.) Cephalopods of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of species known to date. Volume 2. Myopsid and Oegopsid Squids. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No. 4, Vol. 2. FAO, Rome. pp. 148–178.

- Jereb, P., Roper, C.F.E. (2010). Cephalopods of the World. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Volume 2. 6-10. fao.org

- Te Papa: Hooks and Suckers. Blog.tepapa.govt.nz (2008-04-30). Retrieved on 2011-09-30.

- Remeslo, Alexander; Yukhov, Valentin; Bolstad, Kathrin; Laptikhovsky, Vladimir (May 2019). "Distribution and biology of the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni: New data from depredation in toothfish fisheries and sperm whale stomach contents". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 147: 121–127. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2019.04.008.

- Nilsson, Dan-Eric; Warrant, Eric J.; Johnsen, Sönke; Hanlon, Roger; Shashar, Nadav (24 April 2012). "A Unique Advantage for Giant Eyes in Giant Squid". Current Biology. 22 (8): 683–688. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.031. PMID 22425154. no-break space character in

|first2=at position 5 (help) - Bourton, Jody (2010-05-07). "Huge 'monster squid' not fearsome". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Robson, G.C. 1925. On Mesonychoteuthis, a new genus of oegopsid, Cephalopoda. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Series 9, 16: 272–277.

- Ellis, R. 1998. The Search for the Giant Squid. The Lyons Press.

- Griggs, Kim (2003-04-02). "Super squid surfaces in Antarctic". BBC News. Wellington. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- "The Colossal Squid Exhibition - The Squid Files - How big is the colossal squid?". 2008-12-17. Archived from the original on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- "The Colossal Squid". Te Papa. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Tapaleao, Vaimoana (2014-08-11). "Is it a boy? Te Papa gets new colossal squid". New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Ballance, Alison; Meduna, Veronika (16 September 2014). "Colossal squid to give up its secrets". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Richard Black "Colossal squid's big eye revealed". BBC News, April 30, 2008.

- Xavier, José C.; Raymond, Ben; Jones, Daniel C.; Griffiths, Huw (19 October 2015). "Biogeography of Cephalopods in the Southern Ocean Using Habitat Suitability Prediction Models" (PDF). Ecosystems. 19 (2): 220–247. doi:10.1007/s10021-015-9926-1.

- Rosa, Rui; Lopes, Vanessa M.; Guerreiro, Miguel; Bolstad, Kathrin; Xavier, José C. (30 March 2017). "Biology and ecology of the world's largest invertebrate, the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni): a short review" (PDF). Polar Biology. 40 (9): 1871–1883. doi:10.1007/s00300-017-2104-5.

- Sarchet, Penny (11 June 2015). "Colossal squid vs huge toothfish – clash of the deep-sea titans". New Scientist. doi:10.1080/00222933.2015.1040477. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Lu, C.C.; Williams, R. (June 1994). "Contribution to the biology of squid in the Prydz Bay region, Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 6 (2): 223–229. doi:10.1017/s0954102094000349. ISSN 0954-1020.

- Rosa, R. & B.A. Seibel 2010. Slow pace of life of the Antarctic colossal squid. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, published online on April 20, 2010. doi:10.1017/S0025315409991494

- Clarke, M.R. (1980). "Cephalopoda in the diet of sperm whales of the southern hemisphere and their bearing on sperm whale biology". Discovery Reports. 37: 1–324.

- Cherel, Y. & G. Duhamel 2004. "Antarctic jaws: cephalopod prey of sharks in Kerguelen waters" (PDF). (531 KB) Deep-Sea Research Part I 51: 17–31.

- Jereb, P; Roper, C.F.E. Cephalopods of the world : an annotated and illustrated catalogue of cephalopod species known to date. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-106720-8.

- Rosa, Rui; Lopes, Vanessa M.; Guerreiro, Miguel; Bolstad, Kathrin; Xavier, José C. (1 September 2017). "Biology and ecology of the world's largest invertebrate, the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni): a short review" (PDF). Polar Biology. 40 (9): 1871–1883. doi:10.1007/s00300-017-2104-5.

- Jereb, P; Roper, C.F.E. Cephalopods of the world : an annotated and illustrated catalogue of cephalopod species known to date. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-106720-8.

- "Very Rare Giant Squid Caught Alive". South Georgia Island. Archived from the original on 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- "NZ fishermen land colossal squid". BBC News. 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Te Papa's Specimen: The Thawing and Examination Archived April 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved on 2011-09-30.

- Marks, Kathy (March 23, 2007). "NZ's colossal squid to be microwaved". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- Black, Richard (2008-04-28). "Colossal squid comes out of ice". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Ballance, Alison (14 October 2014). "Colossal Squid Revealed". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- "Massive squid may be just a babe". The Star. South Africa.

- "World's biggest squid reveals 'beach ball' eyes". www.terradaily.com. Wellington: AFP. 30 April 2008. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- "Scientists Found Only The Second Intact Colossal Squid — Here's What It Looks Like". 16 September 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "Colossal Squid". Oceana. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Colossal Squid ~ MarineBio Conservation Society". Marine Bio.

Further reading

- Aldridge, A.E. (2009). "Can beak shape help to research the life history of squid?". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 43 (5): 1061–1067. doi:10.1080/00288330.2009.9626529.

- (in Russian) Klumov, S.K. & V.L. Yukhov 1975. Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni Robson, 1925 (Cephalopoda, Oegopsida). Antarktika Doklady Komission 14: 159–189. [English translation: TT 81-59176, Al Ahram Center for Scientific Translations]

- McSweeny, E.S. (1970). "Description of the juvenile form of the Antarctic squid Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni Robson". Malacologia. 10: 323–332.

- Rodhouse, P.G.; Clarke, M.R. (1985). "Growth and distribution of young Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni Robson (Mollusca: Cephalopoda): an Antarctic squid". Vie Milieu. 35 (3–4): 223–230.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni. |

- "CephBase: Colossal squid". Archived from the original on 2005.

- Tree of Life web project: Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa(Te Papa) Colossal Squid Specimen Information

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa(Te Papa) Colossal Squid Images and Video

- Tonmo.com: Giant Squid and Colossal Squid Fact Sheet

- New Zealand Herald: Fishermen haul in world's biggest squid

- National Geographic News: Colossal Squid Caught off Antarctica

- National Geographic News: Colossal Squid Revealed in First In-Depth Look

- USA Today: Colossal Squid Caught in Antarctic Waters

- BBC: Super squid surfaces in Antarctic

- MarineBio: Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni