Christmas Island red crab

The Christmas Island red crab (Gecarcoidea natalis) is a species of land crab that is endemic to Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean.[1][2] Although restricted to a relatively small area, an estimated 43.7 million adult red crabs once lived on Christmas Island alone,[3] but the accidental introduction of the yellow crazy ant is believed to have killed about 10–15 million of these in recent years.[4] Christmas Island red crabs make an annual mass migration to the sea to lay their eggs in the ocean.[5] Although its population is being decimated by the invasion of the yellow crazy ant,[6] as of 2018 the red crab had not been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and it was not listed on their Red List.[7]

| Christmas Island red crab | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| |

| Megalopae of the crab | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Infraorder: | Brachyura |

| Family: | Gecarcinidae |

| Genus: | Gecarcoidea |

| Species: | G. natalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Gecarcoidea natalis Pocock, 1888 | |

| |

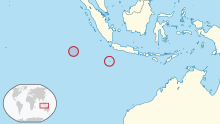

| Distribution map of Christmas Island red crab | |

Description

Christmas Island red crabs are large crabs with the carapace measuring up to 116 millimetres (4.6 in) wide.[8] The claws are usually of equal size, unless one becomes injured or detached, in which case the limb will regenerate. The male crabs are generally larger than the females, while adult females have a much broader abdomen (only apparent above 3 years of age) and usually have smaller claws.[8] Bright red is their most common color, but some can be orange or the much rarer chicken.

Ecology and behaviour

Behaviour

Like most land crabs, red crabs use gills to breathe and must take great care to conserve body moisture. Although red crabs are diurnal, they usually avoid direct sunlight so as not to dry out, and, despite lower temperatures and higher humidity, they are almost completely inactive at night.[8] Red crabs also dig burrows to shelter themselves from the sun and will usually stay in the same burrow through the year; during the dry season, they will cover the entrance to the burrow to maintain a higher humidity inside, and will stay there for 3 months until the start of the wet season. Apart from the breeding season, red crabs are solitary animals and will defend their burrow from intruders.[8]

Migration and breeding

For most of the year, red crabs can be found within Christmas Islands' forests, however, each year they migrate to the coast to breed; the beginning of the wet season (usually October/November) allows the crabs to increase their activity and stimulates their annual migration.[3] The timing of their migration is also linked to the phases of the moon.[5] During this migration, red crabs abandon their burrows and travel to the coast to mate and spawn. This normally requires at least a week, with the male crabs usually arriving before the females. Once on the shore, the male crabs excavate burrows, which they must defend from other males. Mating occurs in or near the burrows. Soon after mating the males return to the forest while the females remain in the burrow for another two weeks. During this period they lay their eggs and incubate them in their abdominal brood pouch to facilitate their development.[3] At the end of the incubation period the females leave their burrows and release their eggs into the ocean, precisely at the turn of the high tide during the last quarter of the moon.[3][5] The females then return to the forest while the crab larvae spend another 3–4 weeks at sea before returning to land as juvenile crabs.[3]

Life cycle

The eggs released by the females immediately hatch upon contact with sea water and clouds of crab larvae will swirl near the shore until they are swept out to sea, where they remain for 3–4 weeks.[5] During this time, the larvae go through several larval stages, eventually developing into shrimp-like animals called megalopae.[8] The megalopae gather near the shore for 1–2 days before changing into young crabs only 5 mm (0.20 in) across. The young crabs then leave the water to make a 9-day journey to the centre of the island.[5] For the first three years of their lives, the young crabs will remain hidden in rock outcrops, fallen tree branches and debris on the forest floor.[5] Red crabs grow slowly, reaching sexual maturity at around 4–5 years, at which point they begin participating in the annual migration.[8] During their early growth phases, red crabs will moult several times. Mature red crabs will moult once a year, usually in the safety of their burrow.

Diet

Christmas Island red crabs are opportunistic omnivorous scavengers. They mostly eat fallen leaves, fruits, flowers and seedlings, but will also feed on dead animals (including cannibalising other red crabs), and human rubbish. The non-native giant African land snail is also another food choice for the crabs.[8] Red crabs have virtually no competition for food due to their dominance of the forest floor.

Predators

Adult red crabs have no natural predators on Christmas Island.[9] An exploding population of the yellow crazy ant though, which is an invasive species accidentally introduced to Christmas Island and Australia from Africa, is believed to have killed 10–15 million red crabs (one-quarter to one-third of the total population) in recent years.[4] In total (including killed), the ants are believed to have displaced 15–20 million red crabs on Christmas Island.[10] During their larval stage, millions of red crab larvae are eaten by fish and large filter-feeders such as manta rays and whale sharks which visit Christmas Island during the red crab breeding season.

Coconut crabs (alternatively known as robber crabs) have also been filmed on Christmas Island preying on red crabs.[11]

Early inhabitants of Christmas Island rarely mentioned these crabs. It is possible that their current large population size was caused by the extinction of the endemic Maclear's rat, Rattus macleari in 1903, which may have limited the crab's population.[12]

Population

Surveys have found a density of 0.09–0.57 adult red crabs per square metre, equalling an estimated total population of 43.7 million on Christmas Island.[3] Less information is available for the population in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, but numbers there are relatively low.[13] Based on genetic evidence, it appears that the Cocos (Keeling) red crabs are relatively recent immigrants from Christmas Island, and for conservation purpose the two can be managed as a single population.[14]

Relationship with humans

During their annual breeding migration, red crabs will often have to cross several roads to get to their breeding grounds and then back to forest. As a result, red crabs are frequently crushed by vehicles and sometimes cause accidents due to their tough exoskeletons which are capable of puncturing tires. To ensure the safety of both populations, crabs and humans, local park rangers work to ensure that crabs can safely make their journey from the center of the island to the sea; along heavily traveled roads, they set up aluminum barriers whose purpose is to funnel the crabs towards small underpasses so that they can safely traverse the roads.[8][5] Other infrastructure to assist the crab migration includes a five-metre-high "crab bridge".[15] In recent years, the human inhabitants of Christmas Island have become more tolerant and respectful of the crabs during their annual migration and are now more cautious while driving, which helps to minimise crab casualties.[5]

References

- Dennis J. O'Dowd & P. S. Lake (1990). "Red crabs in rain forest, Christmas Island: differential herbivory of seedlings". Oikos. 53 (3): 289–292. JSTOR 3545219.

- A. K. Shaw (September 11, 2010). "Christmas Island Red Crabs". Princeton University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Adamczewska, A. M.; Morris, S. (June 2001). "Ecology and behaviour of Gecarcoidea natalis, the Christmas Island red crab, during the annual breeding migration". The Biological Bulletin. 200 (3): 305–320. doi:10.2307/1543512. JSTOR 1543512. PMID 11441973.

- Dennis J. O'Dowd, Peter T. Green & P. S. Lake (2003). "Invasional 'meltdown' on an oceanic island" (PDF). Ecology Letters. 6 (9): 812–817. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00512.x.

- "Red crabs - video footage of the migration". Parks Australia. December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "One Hundred of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) - IUCN Species Survival Commission.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species - 2018-1". International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "Red Crabs, Gecarcoidea natalis" (PDF). Park Australia. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Rachel Sullivan (November 3, 2010). "Red crabs overtake Christmas Island". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- "Yellow crazy ants". Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. March 23, 2011. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "Wonders Of The Monsoon". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Tim Flannery & Peter Schouten (2001). A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York. ISBN 0-87113-797-6.

- Gillespie, Rosemary; Clague, David, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islands. University of California Press. p. 532. ISBN 9780520256491.

- Weeks, A.R.; Smith, M.J.; van Rooyen, A.; Maple, D.; Miller, A.D. (2014). "A single panmictic population of endemic red crabs, Gecarcoidea natalis, on Christmas Island with high levels of genetic diversity". Conservation Genetics. 15 (4): 909–19. doi:10.1007/s10592-014-0588-x.

- "Forget Sydney and San Francisco: Christmas Island crab bridge helps migrating critters beat the traffic". ABC News. December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

Further reading

- Hicks, John W. (December 1987). "Red Crabs: On the March on Christmas Island". National Geographic. Vol. 172 no. 6. pp. 822–831. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

- Christmas Island National Park Website

- 3 minute TV clip showing crabs migrating through a town

- Webpage about Christmas Island, describes crisis of Yellow Crazy ants

- Website showing the crabs of Christmas Island including the red crab migration