Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel

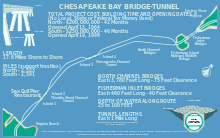

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel (CBBT) is a 17.6-mile (28.3 km) bridge–tunnel crossing at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, the Hampton Roads harbor, and nearby mouths of the James and Elizabeth Rivers in the U.S. state of Virginia. It connects Northampton County on the Delmarva Peninsula and Eastern Shore with Virginia Beach, Norfolk, Chesapeake, and Portsmouth on the western shore and south side / Tidewater which are part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of eight close cities around the harbor's shores and peninsula. The bridge–tunnel originally combined 12 miles (19 km) of trestle, two 1-mile-long (1.6 km) tunnels, four artificial islands, four high-level bridges, approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) of causeway, and 5.5 miles (8.9 km) of northeast and southwest approach roads—crossing the Chesapeake Bay and preserving traffic on the Thimble Shoals and Chesapeake dredged shipping channels leading to the Atlantic. It replaced vehicle ferry services that operated from South Hampton Roads and from the Virginia Peninsula since the 1930s. Financed by toll revenue bonds, the Bridge–Tunnel was opened on April 15, 1964,[1] and remains one of only 11 bridge–tunnel systems in the world, three of which are located in the water dominated Hampton Roads area of Tidewater Virginia.

Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel | |

|---|---|

_crossing_the_North_Channel_of_the_Chesapeake_Bay_in_Northampton_County%2C_Virginia.jpg) Coming down from the high-level portion near the north end. | |

| Coordinates | 37.029966°N 76.085815°W |

| Carries | 4 lanes (4 on bridges, 2 in tunnels) of |

| Crosses | Chesapeake Bay |

| Locale | Virginia Beach and Norfolk, Chesapeake, Portsmouth to Cape Charles, Virginia, U.S. |

| Official name | Lucius J. Kellam Jr. Bridge–Tunnel |

| Maintained by | Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Fixed link: low-level trestle, single-tube tunnels, artificial islands, truss bridges, high-level trestle |

| Total length | 17.6 miles (28.3 km)[1] |

| Clearance below | 75 feet (22.9 m) (North Channel) 40 feet (12.2 m) (Fisherman Inlet) |

| History | |

| Opened | April 15, 1964 (northbound) April 19, 1999 (southbound) |

| Statistics | |

| Toll | Cars $18 (each direction, peak, round trip discount available) E-ZPass |

| |

As of May 2018 the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel has been crossed by more than 130 million vehicles.[2] The CBBT complex carries U.S. Route 13 (US 13), the main north–south highway on Virginia's Eastern Shore on the Delmarva peninsula, and, as part of the East Coast's longstanding Ocean Highway, provides the only straight direct link along the East Coast and Atlantic Ocean, between the Eastern Shore and South Hampton Roads regions, as well as an alternate route to link the Northeast U.S. and points in between with Norfolk and further south to the Carolinas and Florida. The Bridge–Tunnel saves motorists 95 miles (153 km) and 1 1⁄2 hours on a trip between Virginia Beach/Norfolk and points north and east of the Chesapeake and Delaware Valley, River and Bay without going through the traffic congestion in the Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area further west in Maryland and Northern Virginia. From 1995 to 1999, at an additional cost of almost $200 million, the capacity of the above-water portion of bridges on the facility was increased and widened to four lanes. An upgrade of the two-lane tunnels is currently underway.[3] The crossing was officially named the Lucius J. Kellam Jr. Bridge–Tunnel in August 1987, 23 years after opening, honoring one of the civic leaders who had long worked for its development, construction and operation; it continues however to be best known as the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel. The complex was built by and is operated by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, a political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia governed by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission and in cooperation with the state Department of Transportation. Costs are recovered through toll collections. In 2002, a Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) study commissioned by the Virginia General Assembly concluded that "given the inability of the state to fund future capital requirements of the CBBT, the District and Commission should be retained to operate and maintain the Bridge–Tunnel as a toll facility in perpetuity."

Occasionally because of similar names, the Bridge-Tunnel is often confused with the Chesapeake Bay Bridge (also known as the Governor William Preston Lane, Jr. Memorial Bridge) further north in Maryland crossing the middle portion of the Bay from Annapolis to Kent Island on the Maryland Eastern Shore of Delmarva. It was built with two lanes and a higher suspension segment in the middle from 1949 - 1952, with a second parallel wider span of three lanes in 1973. It is one of the longest and highest bridges in the world.

History

Geographic background

In December 1606, the Virginia Company of London sent an expedition to North America to establish a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. After sailing across the Atlantic Ocean from England, they reached the New World at the southern edge of the mouth of what is now known as the Chesapeake Bay.[4] They named the two flanking Virginia points of land /capes like gateposts at the entrance to the long extensive estuary after the sons of their king, James I, the southern Cape Henry, for the eldest and presumed heir, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, and the northern Cape Charles, for his younger brother, Charles, Duke of York (the future King Charles I). A few weeks later they established their first permanent settlement on the southern, mainland, side of the Bay, several miles upstream along the newly named James River at Jamestown on the northern shore on a close-in island for protection, the first permanent settlement in English North America.

Across the Bay, the area north of Cape Charles was located along what became known later as the Delmarva Peninsula. As it bordered the Atlantic Ocean to its east, the region became known as Virginia and neighboring Maryland's Eastern Shore. As the entire colony grew, the Bay was a formidable transportation obstacle for exchanges with the Virginia mainland on the Western Shore. One of the eight original shires of Virginia, Accomac Shire was established there in 1634, eventually becoming the two counties of modern times, Accomack County in the north and Northampton to the south. In comparison to mainland regions, commerce and growth was limited by the need to cross the Bay. Consequently, little industrial base grew there, with the oceanfront peninsula staying predominantly rural with small towns and villages oriented towards life on the waters, and most residents made their living by farming and working as watermen, both on the Bay (locally known as the "bay side") and in the Atlantic Ocean ("sea side").

Ferry system

For the first 350 years, ships and ferry systems provided the primary transportation.

From the early 1930s to 1954, the Virginia Ferry Corporation, a privately owned public service company managed a scheduled vehicular (car, bus, truck) and passenger ferry service between the Virginia Eastern Shore and Princess Anne County (now part of the City of Virginia Beach) on the mainland Western Shore in the South Hampton Roads area. This system, connecting portions of U.S. Route 13, was known as the Little Creek-Cape Charles Ferry. In 1951, the Northern terminus in Delmarva was relocated to a location now within Kiptopeke State Park.

Despite an expanded fleet of large and modern ships by the V.F.C. in the 1940s and early 1950s which were eventually capable of as many as 90 one-way trips each day, the lengthy crossing suffered delays due to heavy traffic and inclement weather.

In 1954, the General Assembly of Virginia (state legislature) created a political subdivision, the Chesapeake Bay Ferry District and its governing body, the Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission. The Commission was authorized to acquire the private ferry corporation through bond financing, to improve the existing V.F.C. ferry service.

Once the Bridge–Tunnel was built by 1964, much of the ferry equipment and vessels used by the Little Creek-Cape Charles Ferry V.F.C. service was then sold and moved north to be redeployed to start the Cape May–Lewes Ferry across the 17-mile (27 km) mouth of the Delaware Bay between Cape May, in New Jersey and Lewes across in Delaware. It still serves transit needs, but the number of pleasure trip passengers increased as the coastal beach resorts developed and grew crowded with vacationers in the next decades, partly due to the improved swifter transportation with highway, bridge, and tunnel access in the region of three states.[5]

Studying a fixed crossing

In 1956, the General Assembly authorized the Ferry Commission to conduct feasibility studies for the construction of a fixed crossing. The conclusion of the study indicated that a vehicular crossing was feasible.[2]

Consideration was given to service between the Eastern Shore and both the Peninsula and South Hampton Roads. Eventually, the shortest route, extending between the Eastern Shore and a point in Princess Anne County at Chesapeake Beach (east of Little Creek, west of Lynnhaven Inlet), was selected. An option to also provide a fixed crossing link to Hampton and the Peninsula was not pursued.[6]

The selected route crosses two Atlantic shipping channels: the Thimble Shoals Channel to Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Channel to the northern Chesapeake Bay. High-level bridges were initially considered for traversing these channels. The United States Navy objected to bridging the Thimble Shoals Channel because a bridge collapse (possibly by sabotage) could cut Naval Station Norfolk off from the Atlantic Ocean. Maryland officials expressed similar concerns about the Chesapeake Channel and the Port of Baltimore.[7]

To address these concerns, the engineers recommended a series of bridges and tunnels known as a bridge–tunnel, similar in design to the Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel, which had been completed in 1957, but a considerably longer and larger facility. The tunnel portions, anchored by four man-made islands of approximately 5 acres (2.0 ha) each, would be extended under the two main shipping channels. The CBBT was designed by the engineering firm Sverdrup & Parcel of St. Louis, Missouri.[7]

Original construction

_entering_the_north_portal_of_the_Thimble_Shoal_Channel_Tunnel_in_Chesapeake_Bay%2C_Virginia_Beach%2C_Virginia.jpg)

In mid-1960, the Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission sold $200 million in toll revenue bonds to private investors, and the proceeds were used to finance the construction of the bridge–tunnel. Funds collected by future tolls were pledged to pay the principal and interest on the bonds. No local, state, or federal tax funds were used in the construction of the project.

Construction contracts were awarded to a consortium of Tidewater Construction Corporation and Merritt-Chapman & Scott Corporation. The steel superstructure for the high-level bridges near the north end of the crossing were fabricated by the American Bridge Division of United States Steel Corporation. Construction of the bridge–tunnel began in October 1960 after a six-month process of assembling necessary equipment from worldwide sources.

The tunnels were constructed using the technique refined by Ole Singstad with the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel, whereby a large ditch was first dug for each tunnel, into which was lowered pre-fabricated tunnel sections cable-suspended from overhead barges. Interior chambers were filled with water to lower the sections, the sections then aligned, bolted together by divers, the water pumped out, and the tunnels finally covered with earth.

The construction was accomplished under the severe conditions imposed by nor'easters, hurricanes, and the unpredictable Atlantic Ocean. During the Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962, much of the partially completed work and a major piece of custom-built equipment, a pile driver barge called "The Big D", were destroyed. Seven workers were killed at various times during the construction. In April 1964, 42 months after construction began, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel opened to traffic and the ferry service discontinued.

The Ferry Commission and transportation district it oversees, created in 1954, were later renamed for the revised mission of building and operating the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel. The CBBT district is a public agency and it is a legal subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The bridge–tunnel is supported financially by the tolls collected from the motorists who use the facility.

Eastern Shore native, businessman, and civic leader Lucius J. Kellam Jr. (1911–1995) was the original Commission's first chairman. In a commentary at the time of his death in 1995, the Norfolk-based Virginian-Pilot newspaper recalled that Kellam had been involved in bringing the multimillion-dollar bridge–tunnel project from dream to reality.

Before it was built, Kellam handled a political fight over the location, and addressed concerns of the U.S. Navy about prospective hazards to navigation to and from the Norfolk Navy Base at Sewell's Point.

Kellam was also directly involved in the negotiations to finance the ambitious crossing with bonds. According to the newspaper article, "there were not-unfounded fears that (1) storm-driven seas and drifting or off-course vessels could damage, if not destroy, the span and (2) traffic might not be sufficient to service the entire debt in an orderly way. Sure enough, bridge portions of the crossing have occasionally been damaged by vessels, and there was a long period when holders of the riskiest bonds received no interest on their investment."

An icon of eastern Virginia politics, Kellam remained chairman and champion of the CBBT throughout the hard times, and the bondholders were eventually paid as toll revenues caught up with expenses. He continued to serve until he was over 80 years old, finally retiring in 1993. He had held the post for 39 years.

The facility was renamed in his honor in 1987, over 20 years after it was first opened to traffic.

First expansion project (completed 1999)

At a cost of $197 million, new parallel two-lane trestles were built both to alleviate traffic and for safety reasons. Immediately after completion of the parallel trestles, traffic was diverted to them and the original trestles and roadway underwent a $20 million retrofit, repairing the wear and tear of 35 years of service and upgrading certain features, such as repaving the road surface. The older portion of the facility was then reopened on April 19, 1999.

The 1995–1999 project increased the capacity of the above-water portion of the facility to four lanes, added wider shoulders for the new southbound portion, facilitated needed repairs, and provided protection against a total closure should a trestle be struck by a ship or otherwise damaged (which had occurred twice in the past); partially for this reason, the parallel trestles are not located immediately adjacent to each other, reducing the chance that both would be damaged during a single incident.

Second expansion project (projected 2017–2023)

_exiting_the_south_portal_of_the_Chesapeake_Channel_Tunnel_in_Chesapeake_Bay%2C_Northampton_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

In 2013, the CBBT Commission approved a project to construct the Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel, with cost estimated at $756 million. The project received three bids, all of which would use a tunnel boring machine. The winning company was German-based Herrenknecht, whose machine was 325 ft (99 m) long. The machine, nicknamed Chessie in a naming contest, was capable of removing 2.4 in (61 mm) of soil per minute, or about 50 ft (15 m) per day. At that rate, it was estimated that the tunnel would be dug within about one year. Construction work began in 2017 to prepare the location of the tunnels, with a pier, shop, and restaurant closed in September 2017. The machine was built in 2018, after some delays, and was shipped to Virginia. Construction is scheduled to begin in 2020, and finish in 2023.[8][9][10][11]

Construction is currently underway to add a second tunnel beside the existing tunnel located on the southern end (Thimble Shoals). After boring, the machine will also be adding the circular concrete segments which will be delivered into the tunnel via mine cars one at a time.

- Tunnel Length: approximately one mile

- Tunnel Diameter: Inner Diameter (prior to roadway and support structure installation): 39 feet - Outer Diameter: 42 feet

- Construction Cost: $755,987,318

- Construction Method: Bored tunnel

- Construction Start (estimate): October 1, 2017

- Construction Completion (estimate): 2023

- Maximum Tunnel Depth (Crown – at its deepest location (mid-channel)): 105 feet below the water surface

- Maximum Tunnel Depth (Invert – from the top of the roadway at its deepest location): 134 feet below the surface

- Soil Removal: The approximate amount of soil to be removed by the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) is 500,000 cubic yards.

- Concrete Sections: The tunnel will consist of approximately 9,000 individual concrete pieces. Approximately 42,000 cubic yards of concrete will be needed to make the tunnel sections.[12]

Third expansion project (projected 2035–2040)

At the northern end, a parallel Chesapeake Channel Tunnel will be added to finish the entire length to become a four lane highway from shore to shore. This project is marked to begin in 2035, which would possibly be open for traffic in 2040, assuming there are no setbacks or delays.

Operations, maintenance, and regulations

Toll collection facilities are located at both ends of the facility. Tolls are paid in each direction. As of 2019, the toll for cars (without trailers) traveling along the CBBT is $14 for off-peak or $18 for peak times (Friday through Sunday during May 15 through September 15).[13] Should a car make a return trip within 24 hours of the first, the second trip across costs $6 for off peak or $2 for peak. Motorcycles pay the same toll as cars without trailers. All other vehicles are charged based on size and purpose and are not subject to the return-trip discount.[14] All tolls must be paid either in cash, debit/credit card, by scrip tickets issued by the CBBT, or via E-ZPass electronic toll collection.[15] The bridge–tunnel began accepting Smart Tag/E-ZPass payments on November 1, 2007.[16][17]

All toll lanes including E-ZPass-only lanes are gated for safety concerns and to turn around inadmissible vehicles. For example:[18]

- Strong winds have blown over certain vehicles.[18] Therefore, some vehicles are banned when the wind speed exceeds 40 miles per hour (64 km/h). Level 6 wind restrictions with hurricane-force winds (at least 70 miles per hour (110 km/h), i.e. approaching the wind speed of a Category 1 hurricane, which is at least 74 miles per hour (119 km/h)), and other inclement weather conditions ban all traffic.[19]

- Hazardous materials and compressed gas require various restrictions and inspections to safeguard the tunnels.[18][20]

- Both tunnels have a height limit of 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m). An over-height truck in April 2007 severely damaged the tunnels. Repairs took three weeks.[18]

- Should police activities, accidents, or closures stop traffic from moving freely, gates prevent drivers from entering and then being forced to either back up within the narrow space or to wait too long in the middle of the bridge–tunnel.[18]

The bridge–tunnel management prohibits bicycles but offers a shuttle van for $15. Cyclists must call ahead.[21]

It is mandatory that the bridge be checked and serviced every five years. Since servicing the bridge takes about five years, the work never stops.[22]

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel is one of only two automobile transportation facilities in Virginia that employs its own police department (the other is the Richmond Metropolitan Authority Toll Road Police). By original charter from the Commonwealth, it has authority to enforce the laws of Virginia.[23] Emergency call boxes are spaced every half-mile (.8 km) along the bridge. The toll schedule, weather advisories, and other information are available at the official website for the bridge.[24]

Tourism

The CBBT promotes the bridge–tunnel as not only a transportation facility to tourist destinations to the north and south, but as a destination itself. For travelers headed elsewhere, the bridge–tunnel can save more than 90 miles (140 km) of driving for those headed between Ocean City, Maryland, Rehoboth Beach, Fenwick Island, and Wilmington, Delaware (and areas north) and the Virginia Beach area or the Outer Banks of North Carolina, according to the CBBT district. Unlike the Interstate highways that travelers would avoid by taking the bridge–tunnel, the roads in the shortcut have traffic lights.[24]

On the Delmarva peninsula to the north of the bridge, travelers may visit nearby Kiptopeke State Park, Eastern Shore National Wildlife Refuge, Fisherman Island National Wildlife Refuge (closed to the public), campgrounds and other vacation destinations. To the south are tourist destinations around Virginia Beach, including First Landing State Park, Norfolk Botanical Garden, Virginia Beach Maritime Historical Museum, Atlantic Wildfowl Heritage Museum, and the Virginia Aquarium and Maritime Science Center.[24]

A scenic overlook is located at the north end of the bridge and was formerly located at South Thimble Island, near the south end. At South Thimble Island, passing ships may include U.S. Navy warships, nuclear submarines, and aircraft carriers, as well as large cargo vessels and sailing ships. A restaurant and gift shop on the island opened in 1964, along with the 625-foot-long (191 m) Sea Gull Pier. Bluefish, trout, croaker, flounder, and other species have been caught from the pier. Since birds use the habitat created by the bridges and islands of the CBBT, birders have travelled to the bridge–tunnel to see them at South Thimble Island and the scenic overlook at the north end.[24] As part of the Thimble Shoal Channel Tunnel twinning, the building housing the restaurant and gift shop closed and access to the pier was prohibited starting at the end of September 2017.[25] The building will be demolished and not replaced, and the pier will reopen to the public at the end of the project in 2022.[26]

Dimensions

Among the key features of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel are two 1-mile (1.6 km) tunnels beneath the Thimble Shoals and Chesapeake navigation channels and two pairs of side-by-side high-level bridges over two other navigation channels: North Channel Bridge (75 ft or 22.9 m clearance) and Fisherman Inlet Bridge (40 ft or 12.2 m clearance). The remaining portion comprises 12 miles (19 km) of low-level trestle, 2 miles (3.2 km) of causeway, and four man-made islands.

The CBBT is 17.6 miles (28.3 km) long from shore to shore, crossing what is essentially an ocean strait. Including land-approach highways, the overall facility is 23 miles (37 km) long (20 miles or 32 kilometres from toll-plaza to toll-plaza)[1] and despite its length, there is only a height difference of 6 inches (152 mm) from the south to north end of the bridge–tunnel.

Man-made islands, each approximately 5.25 acres (2.12 ha) in size, are located at each end of the two tunnels. Between North Channel and Fisherman Inlet, the facility crosses at grade over Fisherman Island, a barrier island which is part of the Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The columns that support the bridge–tunnel's trestles are called piles. If placed end to end, the piles would stretch for about 100 miles (160 km), roughly the distance from New York City to Philadelphia.[27]

Major accidents

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel has suffered three major ship accidents which caused the bridge-tunnel system to be closed.

The first accident occurred in December 1967 when the Mohawk,[28] a coal barge, broke anchor and struck the bridge, closing it for two weeks for repair.[29]

On January 21, 1970 the USS Yancey (AKA-93), a United States Navy attack cargo ship carrying 250 people,[28] was at anchor near the bridge tunnel. During a gale with winds gusting in excess of 50 miles per hour (80 km/h), the Yancey dragged her anchors and hit the bridge stern first, knocking out a 375 foot (114 m) segment of trestle. There were no vehicles on the bridge at the time of the impact, and no one was injured during the incident. During the 42 days it took to replace the damaged span[29] the Navy offered a free shuttle service for commuters using helicopters and LCUs.[30]

In 1972, the bridge was again impacted by a barge which had broken loose, again closing the bridge-tunnel for two weeks while the span was repaired.[29]

The bridge-tunnel is frequently impacted by barges moving through the highly trafficked area; most incidents cause no damage and require a closure of the system for inspections before reopening. The most recent example of this was the June 2011 barge strike, which closed the bridge-tunnel for less than four hours.[31]

See also

- List of bridges

- List of bridge–tunnels

- Lists of tunnels

- List of longest bridges

- Øresund Bridge

- Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line

- Busan–Geoje Fixed Link

References

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel Facts". Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel History". Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel Commission. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- "CBBT Project Description".

- Lisa L. Weaver (June 8, 2000). Learning Landscapes: Theoretical Issues and Design Considerations for the Development of Children's Educational Landscapes (PDF) (Thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- "History / Cape May-Lewes Ferry". Cmlf.com. February 6, 1963. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel". Roadstothefuture.com. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- Forster, Dave (April 3, 2014). "Building the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel". pilotonline.com. The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel restaurant, gift shop closing for good". 13 ABC News Now. September 6, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- "CBBT Tunnel Boring Machine Construction Completed". Shore Daily News. September 21, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Gordon Rago (February 15, 2019). "Project to expand Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is year behind schedule". Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Cindy Riley (August 19, 2019). "Crews Prep for Virginia's New $756M Tunnel". Construction Equipment Guide. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- "CBBT Project Description". www.cbbt.com. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- "Toll Schedule" (PDF). www.cbbt.com. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "Toll Schedule". Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- Shockley, Ted (June 7, 2006). "A non-stop, no-cash bridge–tunnel trip?". The Daily Times. Archived from the original on June 25, 2006. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel Announces the Opening of an E-ZPass Virginia Customer Service Center". Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel. Retrieved October 7, 2007.

- "CBBT Commission Selects System Consultant for Electronic Toll Collection Project". Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- "importance of gated lanes at the cbbt". Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- "Weather". Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- "Hazardous materials". Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- "Bicycling and Walking in Virginia: General Information: Crossing the Waters". Virginia Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel". Modern Marvels. Season 7. Episode 107. February 7, 2001.

- Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission of the Virginia General Assembly. "The Future of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel" (PDF). House Document No. 18. p. 53. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel/Follow The Gulls." brochure, "Eighteenth Edition. This brochure has been prepared exclusively for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District", 2007

- Pascale, Jordan (September 28, 2017). "Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel restaurant shut down early. You can still see a sunset before the island closes". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- Pascale, Jordan (July 27, 2016). "Dragados awarded $756 million contract for new tube of Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel" (PDF). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2009. Eighteenth Edition. Brochure.

- "Will They Stay Standing?". tribunedigital-dailypress. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- Hamilton, Martha M. (March 19, 1984). "Bay Tunnel Survives Dark Days". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "Yancey". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Barge Strikes Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in Second Similar Accident - GES". GES. September 19, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. |

- Official website

- Roads to the Future: Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel

- information from Norfolk Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Virginian-Pilot newspaper commentary on long-time CBBT Chairman Lucius J. Kellam Jr. at the time of his death in 1995

- Fisherman's Island National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- General Assembly JLARC study of the CBBT in 2002