Bridlington

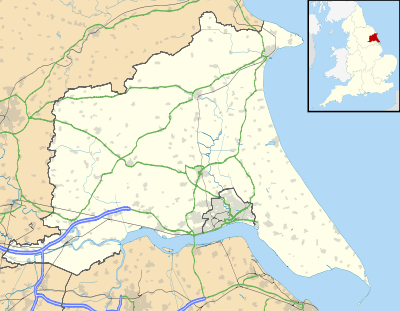

Bridlington is a coastal town and civil parish on the Holderness Coast of the North Sea, promoted as "Lobster Capital of Europe".[2][3] It belongs to the unitary authority and ceremonial county of the East Riding of Yorkshire, about 28 miles (45 km) north of Hull and 34 miles (55 km) east of York. The Gypsey Race flows through the town and enters the North Sea at its harbour. The 2011 Census gave a parish population of 35,369.[1] As a minor sea-fishing port with a working harbour, it is known for shellfish. It contains small businesses in the manufacturing, retail and service sectors, its main trade being summer tourism. The town is twinned with Millau, France, and Bad Salzuflen, Germany.[4] One of the UK's coastal weather stations is located there. The Priory Church of St Mary and associated Bayle Gate are Grade I listed buildings on the site of an original Augustinian Priory.

| Bridlington | |

|---|---|

South Sands with The Spa in the background | |

Arms of Bridlington Town Council | |

Bridlington Location within the East Riding of Yorkshire | |

| Population | 35,369 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TA1866 |

| • London | 180 mi (290 km) S |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BRIDLINGTON |

| Postcode district | YO15/YO16 |

| Dialling code | 01262 |

| Police | Humberside |

| Fire | Humberside |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament |

|

| Website | www.bridlington.gov.uk |

History

.jpg)

%2C_Yorkshire%2C_England-LCCN2002708301.jpg)

The town's origins are uncertain, but archaeological evidence shows habitation in the Bronze Age and in Roman Britain. The settlement at the Norman conquest was called Bretlinton. It later became Berlington, Brellington and Britlington, before settling under its modern name in the 19th century.[5] It is mentioned in the Domesday Book as Bretlinton.[6] The several suggested origins of the name all follow the Anglo-Saxon custom of naming a person with a settlement type. Here the personal names put forward have included Bretel, Bridla and Berhtel, attached to -ingtūn, a Saxon expression for a farm.[7][8]

The date of earliest habitation at Bridlington is unknown, but the 2.5-mile-long (4 km) man-made Danes Dyke at nearby Flamborough Head goes back to the Bronze Age.[9] Some writers believe that Bridlington was the site of a Roman station.

A Roman road from York, now known as Woldgate, can be traced across the Yorkshire Wolds into the town. Roman coins have been found: two Roman hoards in the harbour area, along with two Greek coins from the 2nd century BC — suggesting that the port was in use long before the Roman conquest of Britain.[10]

It has been suggested that a Roman maritime station, Gabrantovicorum, stood near the modern town.[11] In the early 2nd-century Ptolemy described what was probably Bridlington Bay in his Geography as Γαβραντουικων Ευλίμενος κόλπος "Gabrantwikone bay suitable for a harbour". No sheltered ancient harbour has been found, but coastal erosion would have destroyed any traces, and any Roman installation in the vicinity of the harbour.

In the 4th century, Count Theodosius established signal stations on the North Yorkshire coast to warn of Saxon raids. Flamborough Head is also believed to have had one such station (probably on Beacon Hill, now a gravel quarry). From the headland, Filey, Scarborough Castle and the Whitby promontory can all be seen. A fort at Bridlington would have made a good centre of operations for these forts. A line of signal stations stretching south around the broad Bridlington Bay has also been suggested.[10][12] This counterpart to the northern chain would have guarded a huge and accessible anchorage from barbarian piracy.

Near Dukes Park are two bowl barrows known as Butt Hills, now designated as Ancient Monuments and recorded in the National Heritage List for England maintained by Historic England.[13][14] Also nearby are the remains of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery on a farm outside of Sewerby.[15][16][17]

In the Second World War, Bridlington suffered several air raids with a number of deaths and much bomb damage. The Royal Air Force had various training schools in the town collectively known as RAF Bridlington, with one unit, No. 1104 Marine Craft Unit, continuing until 1980.[18][19][20]

Manor

Domesday Book, the earliest known reference to Bridlington, records that Bretlinton headed the Hunthow Hundred held by Earl Morcar, which passed into the hands of William the Conqueror by forfeiture.[10] The survey also records the effect of the Harrying of the North as the annual value of the land had decreased from £32 in the time of Edward the Confessor to eight shillings at the time of the survey and comprised:

"two villeins, and one socman with one and a half Carucate. The rest is waste."[10]

The land was given to Gilbert de Gant, uncle of King Stephen, in 1072.[10] It was inherited by his son Walter and thereafter appears to follow the normal descent of that family. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the manor remained with the crown until 1624 when Charles I granted it to Sir John Ramsey, who had recently been created the Earl of Holderness.[10] In 1633, Sir George Ramsey sold the manor to 13 inhabitants of the town on behalf of all the tenants of the manor. In May 1636, a deed was drawn up empowering the 13 men as Lords Feoffees or trust holders of the Manor of Bridlington.[17]

Social and political

Walter de Gant founded an Augustinian priory on the land in 1133, which was confirmed by Henry I in a charter.[21] Several succeeding kings confirmed and extended Walter de Gant's gift: King Stephen granting in addition the right to have a port; King John gave prior permission to hold a weekly market and an annual fair in 1200; Henry VI allowed three annual fairs, on the Nativity of Mary, and Deposition of and the Translation of Saint John of Bridlington in 1446.[10] In 1415 Henry V visited the Priory to give thanks for victory at the Battle of Agincourt.[22] The town began to grow in importance and size around the site of the dispersed priory.[17]

In 1643 Queen Henrietta Maria of France landed at Bridlington with troops to support the Royalist cause in the English Civil War before proceeding to York, which became her headquarters.[10]

Industrial

The town was originally two settlements that merged over time. The Old Town was about one mile (1.6 km) inland and the Quay area where the modern harbour lies. In 1837, an Act of Parliament enabled the old wooden piers to be replaced with two new stone piers to the north and south.[17] Apart from landing fish, the port was used to transport corn. The 1826 Corn Exchange can still be seen in Market Place. There used to be mills in the town for grinding, which led to some breweries starting locally, but like most industry, these had petered out by the latter part of the 20th century.[23]

Governance

Bridlington is within the boundary of the unitary authority of the East Riding of Yorkshire. It provides the three authority wards of Bridlington North, Bridlington South and Bridlington Old Town and Central. In total the wards return eight councillors out of a total of 67.[24] The civil parish is formed by the town of Bridlington and the villages of Bessingby and Sewerby and is run by a town council with twelve councillors. There are three Town Council wards each returning four councillors.[25]

The Town Council coat of arms is described as:

Per Sable and Argent three Gothic Capital letters B counterchanged on a Chief embattled of the second two Barrulets wavy Azure and for the Crest Issuant from a Coronet composed of eight Roses set upon a rim of a Sun rising Gules.

with the motto:

Signum Salutis Semper

meaning Always the bringer of good health.[26]

Bridlington is within the boundary of the East Yorkshire parliamentary constituency. The constituency is a large, mostly rural one covering the northern part of the county. It also includes the towns of Pocklington, Market Weighton and Driffield. Its size and shape correspond to the old East Yorkshire/North Wolds District that was a part of the old county of Humberside.

The town has been subject to several changes in parliamentary constituencies. From 1290 to 1831 it was part of the large Yorkshire constituency represented by two members until 1826 when it was granted an additional two members. Thereafter it was part of the East Riding of Yorkshire constituency until 1885, returning two members. Further reform reduced the boundaries again, and the town was part of the single member Buckrose seat until 1950. From 1950 to 1997, Bridlington had its own MP until reform extended the boundary to include more countryside as the single seat East Yorkshire constituency.

Bridlington was designated a municipal borough in 1899. After local government re-organisation in 1974 it was included in the new county of Humberside, which caused much local resentment among residents who objected to being excluded from Yorkshire. The town became the administrative centre of a local government district, initially called the Borough of North Wolds but later changed to the Borough of East Yorkshire. The district disappeared when the county of Humberside was abolished in the 1990s, the new East Riding of Yorkshire unitary authority absorbing it and the neighbouring county districts, and Bridlington no longer has any formal local government administrative status above town council level.

Geography

Bridlington lies 19 miles (31 km) north-north-east of Beverley, 16 miles (26 km) south-east of Scarborough, 11 miles (18 km) north-east of Driffield and 24 miles (39 km) north of Kingston upon Hull, the principal city in the county. It is 179 miles (288 km) north of London. The town ranges in elevation from sea level at the beaches to 167 feet (51 m) on Bempton Lane on the outskirts. The Gypsey Race river flows through the town, with the last 1⁄2 mi (800 m) below ground after disappearing from sight at the Quay Road Car Park. The solid geology of the area is mainly from the Cretaceous period and consists of Chalk overlain by Quaternary Boulder clay. The chalk is exposed as the land rises to the north of the town (where a cliff, probably formed during the last interglacial, extends inland at right angles to the present sea cliff) and forms the promontory of Flamborough Head.[27]

Bridlington is a seaside resort in an area which is said to have the highest coastal erosion rate in Europe.[28] Southward the coast becomes low, but northward it is steep and very fine, where the great spur of Flamborough Head projects eastward. The sea front is protected by a sea wall and a wide beach encouraged by wooden groynes which trap the sand.[28] Offshore, the Smithic Sands sandbank stretches out into the bay.[29] These are an important habitat for many marine species.[28] Both Bridlington North and south beaches have won EU environmental quality awards over a number of years.[30]

The Hull to Scarborough railway line divides the town from south west to north east and marks where the Old Town begins to the north of the line. The Old Town has some retail businesses and the Industrial Estates as well as large residential areas. To the south of the line is where the tourist attractions lie, as well as holiday accommodation and some residential areas. As the town has grown, it has incorporated the village of Hilderthorpe.

Climate

The climate is temperate with warm summers and cool, wet winters. The hottest months of the year are from June to September, with temperatures reaching an average high of 19 °C (66 °F) and falling to 12 °C (54 °F) at night. The average daytime temperature in winter is 7 °C (45 °F) during the day and 2 °C (36 °F) during the night.[31]

| Climate data for Bridlington, 15 m asl, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 52.8 (2.08) |

43.3 (1.70) |

48.0 (1.89) |

47.8 (1.88) |

39.0 (1.54) |

56.9 (2.24) |

44.5 (1.75) |

56.7 (2.23) |

53.5 (2.11) |

55.6 (2.19) |

61.3 (2.41) |

61.5 (2.42) |

620.8 (24.44) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.2 | 9.0 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 10.6 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 117.1 |

| Source: Met Office[31] | |||||||||||||

Demography

| Population[1][32][33] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Total | 3,773 | 4,422 | 5,034 | 5,637 | 6,070 | 6,846 | 6,642 | 6,840 | 10,023 | 11,281 | 16,604 | 19,705 | 24,661 | 26,023 | 33,837 | 35,369 |

2001 census

The 2001 UK census showed that the population was split 47.4% male to 52.6% female. The religious constituency was made of 77% Christian, 0.14% Buddhist, 0.03% Jewish, 0.196% Hindu, 0.04% Sikh 0.22% Other and the rest (more than 22%) stating no religion or not stating at all. The ethnic make-up was 98.7% White, 0.43% Mixed Ethnic, 0.08% Black/Black British, 0.19% Chinese/Other Ethnic and 0.49% Asian/British Asian. There were 16,237 dwellings.[32]

2011 census

The 2011 UK census showed that the population was split 48.2% male to 51.8% female. The religious constituency was made of 66.2% Christian, 0.2% Buddhist, 0.1% Muslim, 0.1% Hindu, 0.1% Sikh, 0.0% Other and the rest (33.3%) stating no religion or not stating at all. The ethnic make-up was 98.5% White British, 0.7% Mixed Ethnic, 0.2% Black British, 0.5% Chinese/Other Ethnic and 0.6% British Asian. There were 17,827 dwellings.[1]

Economy

From early in the history of Bridlington, a small fishing port grew up near the coast, later known as Bridlington Quay. After the discovery of a chalybeate spring, the Quay developed in the 19th century to become a seaside resort.[10] Bridlington's first hotel was opened in 1805 and it soon became a popular holiday resort for industrial workers from the West Riding of Yorkshire. A new railway station was opened on 6 October 1846, between the Quay and the historic town.

The area around the new railway station was developed and the two areas of the town were brought together. Bridlington's popularity has declined along with the industrial parts of the north and the rising popularity of cheap foreign holidays. Although the fishing fleet has also declined, the port remains popular with sea anglers for day trips along the coast or further out to local shipwrecks. Bridlington has lucrative export markets for shell fish to France, Spain and Italy, said to be worth several million pounds a year.[34]

Culture and community

Bridlington is served by the Bridlington Free Press newspaper, the East Riding Mail also serves the seaside town. Yorkshire Coast Radio is the towns local commercial radio station and provides local news and information. BBC Radio Humberside and Viking FM do broadcast to the town to and the Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire region. Jake Thackray's song "The Hair of the Widow of Bridlington"[35] mocked Bridlington for the small-mindedness of its inhabitants.

The town is twinned with Millau in France and Bad Salzuflen in Germany.[4] The twinning arrangement dates back to 1991 and the French and German towns are also twinned with one another. Visits from the twin towns occur every two years, with the Bridlington visits to the twin towns occurring in the alternate years.[36]

There are three main parks in the town. Queen's Park is a small open area at the junction of the B1254 and Queensgate. Westgate Park is a mostly wooded area lying between Westgate and the A165 on the outskirts of the town. The largest open area is Duke's Park which lies between Queensgate and the railway line. It is home to Bridlington Sports & Community Club, a skate park and Bridlington Town Football Club. In addition to these sporting facilities, there is a Sports Centre on the outskirts located on Gypsey Road. It has a general purpose sports hall, equipped gymnasium and squash courts. In January 2014 Bridlington Leisure World, on the Promenade, that provided swimming facilities, as well as a gymnasium and indoor bowling rinks closed for redevelopment. A temporary Olympic legacy pool was opened by Jo Jackson in January 2014 at the Bridlington Sports Centre on Gypsey Road,[37] while Leisure World was being rebuilt with an original expected completion of summer 2015.[38] The new facility opened on 23 May 2016,[39][40] with an official opening on 1 July 2016 by Rebecca Adlington, Gail Emms and Dean Windass.[41]

The town has a public library located on King Street. Within the triangle of Station Avenue, Station Road and Quay Road are the Town Hall, Magistrates Court and several other government buildings. On South Marine Drive there is an RNLI Life Boat Station. There has been a Life Boat in the town since 1805 and is manned entirely by volunteers.[42] The Life Boat station received a new Shannon class lifeboat in 2018.[43] The lifeboat house was redeveloped to accommodate the new vessel.[44] Close to the junction of the A165 with the A614 is the Bridlington Hospital[45] and the Ambulance Station and on the opposite side closer to the town centre is the fire station, established in 1960, with a mix of full-time and on-call crew.[46] There is a Post Office & Depot located not far from the level crossing on Quay Road.

Town crier

David Hinde, who lived in the nearby village of Bempton and was a member of the Ancient and Honourable Guild of Town Criers[47] and the Loyal Company of Town Criers,[48] was appointed in the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Year of 2012 by Bridlington Town Council. He was the first town crier in Bridlington since 1901. On 23 July 2013 Hinde gave a special proclamation outside Bridlington Priory, prior to the visit of Prince Charles and HRH Duchess of Cornwall, which was part of the special "Priory 900" celebrations.[49]

On 17 August 2013, at the town's Sewerby Park, Hinde's cry was recorded at 114.8 decibels.[50] Hinde appeared as the Walmington on Sea town crier in the 2016 film Dad's Army.[51]

Landmarks

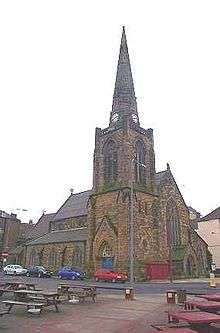

Bridlington Priory, also known as the Priory Church of St Mary, is a Grade I listed building. It was built on the site of an Augustinian Priory, hence its name. The Priory was once fortified and the Bayle Gate nearby is what remains of that fortification and is also a Grade I listed building.[52][53] It has a good-sounding ring of eight bells (tenor c. 24 cwt) with a long draft. It also has a large four-manual organ that boasts the widest "scaled" 32-foot reed (contra tuba) in the United Kingdom. Bridlington's War memorial is located in a small triangular garden at the junction of Prospect Street and Wellington Road. It was officially unveiled on Sunday 10 July 1921 by Captain S. H. Radcliffe, C.M.G., R.N.[54]

The Bridlington Spa was originally opened in 1896, in its heyday Bridlington was a leading entertainment resort thanks to this nationally famous dance venue where many well-known entertainers appeared, including David Bowie and Morrissey. By 2005 the condition of the building had deteriorated to the point where East Riding of Yorkshire Council had to take the decision to undertake a full and thorough refurbishment of the entire Spa facility between 2006 and 2008 to ensure that it would be fit for the demands of a changing market in the 21st century. It has since again begun to attract 'big' names from the world of entertainment: in 2013 indie rock bands the Kaiser Chiefs and Kasabian, Irish band The Script and Joe McElderry all performed at the venue, attracting large crowds.[55]

In 2014 blue plaques were installed for Herman Darewski, composer and conductor of light music,[56] and for Wallace Hartley, leader of the orchestra playing as the Titanic sank.[57] Hartley led an orchestra in the town in 1902.[57] Darewski was Musical Director for the town in 1924–1926 and 1933–1939.[56]

Transport

Bridlington is served by Bridlington railway station, on the Yorkshire Coast Line that runs between Hull and Scarborough. The station opened on 6 October 1846 between the Quay and the Old Town.[58]

East Yorkshire Motor Services, who have a depot[59] in the town, run nine local bus services and six services to out of town destinations including York, Scarborough, Driffield, Beverley and Hull.[60] Additionally, Yorkshire Coastliner also run a service between the town to Filey, Malton, York, Tadcaster and Leeds.

The town lies at the junction of two main trunk roads. The A165 between Hull and Scarborough and the A614 between the town and Nottingham. The route of the A614 was extended in 1996 to run over the route previously known as the A166 which went to York.

Four land trains run in Bridlington: the Yorkshire Rose, Yorkshire Lass and Yorkshire Lad and the Spalight Express.[61] Two trains run on the North Promenade between Leisure World and Sewerby Hall and Gardens linking Bridlington town centre with the summer car parks. One Land Train runs on the South Promenade linking Bridlington town centre to the park and ride and South Cliff Caravan Park.[62] In the 1970s and 1980s there were two trains—the Burlington Bertie and Bridlington Belle.[63]

Education

Primary

There are seven primary schools in the Bridlington Civil Parish, Burlington Infant and junior can be counted together. All schools are mixed gender and cater for pupils between three or four and eleven years of age. Bay Primary School is located on St Alban Road with 335 pupils.[64] Burlington Infant School is located in Marton Road and has 239 children.[65] Burlington Junior School is also located on Marton Road has 320 pupils.[66] Hilderthorpe Primary School is located on Shaftesbury Road with 328 pupils.[67] Martongate Primary School is located in Martongate and has 424 pupils.[68] Quay Academy is located in Oxford Street with 390 pupils.[69] Our Lady and Saint Peter RC Primary School, built in 1977, (formerly St. Mary's R.C. Primary School) is located on George Street and has 210 pupils.[70] New Pasture Lane Primary School is located in Burstall Hill with 177 pupils.[71]

Secondary

Bridlington School is a specialist Sports and Design & Technology College for eleven- to eighteen-year-old mixed gender children. Located on Bessingby Road on the outskirts of the town, it has a capacity of 1,244 pupils.[72] There have been many notable past pupils. There is also Headlands School located on Sewerby Road. It caters for mixed gender children aged between eleven and eighteen years old. It has a partnership with the town's other secondary school. It has a capacity of 1,485 pupils.[73]

Further and higher education

East Riding College provides tertiary education for anyone over the age of sixteen. Located on St Mary's Walk, it is close to Bay Primary School. Courses cover both academic and vocational subjects.[74]

Health services

All six GP practices closed their lists to new patients in 2016 because of problems with premises and shortage of staff. The town has an elderly population which puts a demand on health services. In May 2018 they were forced by NHS England to reopen their lists, although there was no funding for the proposed Health and Wellbeing Centre which had been hoped would have housed five surgeries.[75][76]

Religious sites

The prime place of Christian worship in the town is the Priory Church of St Mary, known as the Priory, in Church Green. Christ Church on Quay Road next to the war memorial was built in 1841 by Gilbert Scott. Originally a chapel of ease, it became a parish church in 1871 and is now a Grade II listed building.[77]

Emmanuel Church on Cardigan Road is a modern red brick building, part of the Church of England. The Harbourside Evangelical Church can be found in a side road off Bridge Street leading to the harbour. The Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses is located on Station Avenue. The Cornerstone Church, formerly known as The Chapel Hall, is an Evangelical Church in St John's Walk.[78] There has been a Baptist church in the town since 1698, with the current building located on the corner of Quay Road and Portland Place.[79] On the corner of St John Street and Brett Street is the Free Presbyterian Church.[80] There is an independent Evangelical Church in Ferndale Terrace called the Calvary Chapel by the Sea.[81]

There has been a strong Methodist Church presence in the town since 1770. The various strands have joined together over the years and as a result so have the locations. St John's Burlington Methodist Church on St John's Street is now home to the town's Methodist congregation. The chapel in the Promenade lasted from 1852 until 1957 and was part of the United Methodist Free Church. The Primitive Methodists established a chapel in St John Street in 1833, but moved to a new location nearby in 1849. This in turn was rebuilt in 1877 and lasted until 1970. The Primitive Methodists also had a chapel, known as the Central Methodist Church, on the Quay in 1833. They moved to Chapel Street in 1870 and built a larger premise on that site in 1878. in 1969 they joined with the Chapel Street Methodist Church. The Chapel Street Methodist Church was in existence in 1810 in what was originally Back Street. This was rebuilt in 1873 and lasted until 1999 when they became the last Methodist congregation to unite at the present chapel.[82]

The Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady & St Peter is located in Victoria Road. The Catholic Parish had been without a permanent mission in the town for a very long time. A previous 1886 building in Wellington Road had not provided sufficient space when a mission was eventually granted. The modern premises were built in 1893–94 by Arthur Lowther. The church hall adjacent was built in 1963. The connection to the sea is evident on the dedication to Our Lady, also known as the Star of the Sea, and to St Peter, Patron Saint of Fishermen. The convent in the High Street is associated with the church and though now run by the Sisters of Mercy, was originally Dominican.[83]

Sport

The town is the home of semi-professional Bridlington Town A.F.C., founded in 1918, refounded in 1994, and now playing in the Northern Counties East League Premier Division (NCEL). Their home ground is the stadium on Queensgate. The team's honours include winning the FA Vase in 1993, three NCEL Premier Division titles and 15 East Riding County FA Cups.[84] The town also has a junior football club, Bridlington Rangers, with teams playing in different age groups of the Hull Boys Sunday Football League. Bridlington Sports Club plays in the Humber Premier League.

In cricket the first team of Bridlington Cricket Club play in the York & District Senior league division 1. The club also runs three Saturday league teams and junior teams.[85]

The town also has a rugby union club: Bridlington Rugby Union Football Club, who play next door to Bridlington Town A.F.C. at Dukes Park. The club field two senior men's teams, a women's team and numerous junior sections.[86] The Men's 1st XI play in Yorkshire 1 for the 2019 season, after spending three years playing in North east 1.[87][88] They also reached the final of the RFU National Intermediate Cup held at Twickenham on 4 May 2013, where they lost 22–30 to Brighton Blues.[89]

Bridlington Hockey Club have been in existence for over 100 years and currently play their home matches at Bridlington Astro Centre on Bessingby Road. The club currently fields two ladies sides and a junior development section for girls and boys. An annual hockey festival is run by the club, with both men's and women's tournaments. A new format has been added to the festival for 2014, with the opportunity for players to also play mixed matches (men & women together).[90]

Other sports played around Bridlington include tennis and pétanque.

Bridlington hosted the start of the first Tour de Yorkshire in 2015,[91] the start of the second stage in 2017 and the start of third stage of the event in 2019.[92]

Notable people

Natives

- William of Newburgh, the 12th-century English chronicler and historian, was born in Bridlington.[93]

- William Kent (1686–1748), architect, landscape architect and furniture designer was born in the town.[94]

- Sir John Major, 1st Baronet of Worthlingworth Hall was born in Bridlington in 1698. The merchant and member of Parliament died in 1781.[95]

- Benjamin Fawcett, the woodblock colour printer and ornithologist, was born in the town in 1808.[96]

- Henry Freeman was a Whitby fisherman and lifeboatman who was born in the town.[97]

- A. E. Matthews was born in Bridlington in 1869. The stage and film actor featured in the 1956 version of Around the World in 80 days, Doctor at Large and Carry On Admiral.[98]

- Thomas Fenby was a Liberal politician and blacksmith who was born in the town in 1875. During his life his was Mayor of Bridlington as well as representing the town as MP. He died at his Bridlington home in 1956.[99]

- Cecil Burton (1887–1971), the cricketer and former Yorkshire County Cricket Club captain, was born in the town, as was his younger brother Claude Burton (1891–1971), who also played for Yorkshire.[100]

- Francis Johnson CBE (1911–95) was born in Bridlington and was a renowned church architect.[101]

- Gordon Lakes, the former Deputy Director General of the Prison Service, was born in the town in 1928. He is credited with helping to achieve improved working conditions among UK prisons.[102]

- Bob Wallis (1934–1391), jazz musician, was born in Bridlington. He had some success in the British charts in the late 1950s and early 60s. His father was harbourmaster in the town.[103]

- David Pinkney, businessman and auto racing driver competing in the British Touring Car Championships, was born in the town on 5 July 1952.[104]

- Andrew Dismore, the Labour politician and lawyer was born in the town on 2 September 1954. He was educated at Bridlington School.[105]

- Mark Herman, film director and screenwriter, was born in the town in 1954. Among his best-known works are Brassed Off, Little Voice and The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.[106]

- Angela Eagle and her twin sister Maria Eagle, both Labour politicians, were born in the town on 17 February 1961.[107]

- Craig Short, professional footballer and manager, born in Bridlington on 25 June 1968. He has played at the highest levels of both the English and Turkish League Systems, including Derby County, Everton, and Blackburn[108]

- Richard Cresswell, professional football player was born in Bridlington on 20 September 1977. He started his career with York City F.C. before playing in higher divisions of the English League System.[109][110]

- Adam Khan, racing driver, was born in the town on 24 May 1985.[111]

- Charlie Heaton is an English actor and musician, known for playing Jonathan Byers in the Netflix supernatural drama series Stranger Things.[112]

- Stephen W. Parsons, musician, composer, songwriter and music producer.[113]

- Rosie Jones, comedian and writer.[114]

Residents

- John Twenge (St John of Bridlington), a 14th-century English saint, was a Canon of Bridlington Priory. He was born less than 10 miles (16 km) from the town in Thwing.[115]

- David Hockney used to own a house in Bridlington, at which an assistant drank a cleaning product and died in March 2013.[116][117]

Twin towns – sister cities

As you enter Bridlington via car, the entrance sign shows the twin town names.

See also

- Burlington, Ontario was named after Bridlington by John Graves Simcoe.

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Bridlington Parish (1170211298)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Why Bridlington is the lobster capital of Europe". Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Bridlington Crowned The Lobster Capital of Europe". Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "UK Twin Towns". Dorset Twinning Association. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- "History of Bridlington". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- /%7B%7B%7Bname%7D%7D%7D/ Bridlington in the Domesday Book. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Watts (2011). Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-names. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0521168557.

- Mills, A. D. (1998). Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford Paperbacks. p. 76. ISBN 978-0192800749.

- "Danes' Dyke at Flamborough". UK Attraction. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "History, topography, and directory of East Yorkshire (with Hull)". T Bulmer & Co. 1892. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Thompson, J. (1821). Historical Sketches of Bridlington. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown. p. 2. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "The Romans in East Yorkshire" (PDF). East Yorkshire Local History Society. 1960. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Historic England. "Western bowl barrow of a pair known as the Butt Hills (1013620)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Historic England. "Eastern bowl barrow of a pair known as the Butt Hills (1013619)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Historic England. "Bowl barrow, 500m SSW of Buckton Barn (1013623)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Historic England. "Bowl barrow, 500m south of Buckton Barn (1013624)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Sheahan, J. J.; Whellan, T (1856). History & Topography of the City of York and the Ainsty Wapentake and the East Riding of Yorkshire Vol. 2. J Green.

- Kench, Simon (19 February 2018). "Extraordinary book details Brid bomb damage". Bridlington Echo. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "RAF Bridlington [concept] · IBCC Digital Archive". ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "Notebook Regarding Training with ETS Course 314 at RAF Bridlington, July 1941 – November 1941". iwm.org.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "The Foundation of the Bridlington Priory". Bridlington.net. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Wilson, Mike (15 September 2006). "St. John of Bridlington". Bridlington Free Press. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- "Bridlington History". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Authority Wards and Councillors". East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Councillors". Bridlington Town Council. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Coat of Arms". Bridlington Town Council. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Dakyns, J. R.; Fox-Strangeways, C. (1885). The Geology of Bridlington Bay. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OL 24171021M.

- "Erosion & Flooding in the Parish of Bridlington". Coastal Observatory. University of Hull. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Coastal processes" (PDF). East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "ENCAMS Seaside Award 2013". Keep Britain Tidy. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington 1981–2010 climate normals". Met Office. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- UK Census (2001). "Local Area Report – Bridlington Parish (1543504339)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Population at Censuses". GB Historical GIS/University of Portsmouth. 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "New Bridlington shellfish dispute threatens". FISHupdate trade news site. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- "The Hair of the Widow of Bridlington". Jakethackray.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Millau Twinning Association". Bridlington Town Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Jo Jackson opens Olympic legacy pool in Bridlington". BBC News. BBC. 29 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Bridlington Leisure World closes for £20m redevelopment". BBC News. BBC. 12 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "Leisure World redevelopment". East Riding Leisure. East Riding of Yorkshire Council. 11 April 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Rebuilt £25m leisure centre opens in East Yorkshire". BBC News. BBC. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Official opening ceremony". East Riding of Yorkshire Council. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- "Bridlington Life Boat". RNLI. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington Lifeboat Officially Named". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 22 April 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "New Bridlington Lifeboat Station Complete". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 26 September 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "Bridlington & District Hospital". National Health Service, York. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington Fire Station". Humberside Fire & Rescue Service. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "ahgtc.org.uk". ahgtc.org.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "lcoftc.co.uk". lcoftc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Visit to Yorkshire". Princeofwales.gov.uk. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Hear ye! I'm loudest crier in all the land". Hull Daily Mail. 26 August 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Pidd, Helen (12 August 2015). "Bridlington to twin with fictional Dad's Army town". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Historic England. "Parish Church of St Mary (1346530)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Historic England. "The Bayle Gate (1346512)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Wilson, Mike. "War Memorial". Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Kasabian announced as latest huge name for Spa Bridlington". Brdilington Free Press. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Darewski Day at the Spa Royal Hall". bridlington.net. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- "Blue Plaque Unveiling at Bridlington Spa". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Body, G (1988). PSL Field Guides – Railways of the Eastern Region Volume 2. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 1-85260-072-1.

- "History – East Yorkshire Motor Services Ltd". Eyms.co.uk. 5 October 1926. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Local Transport". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington Land Trains". East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "Sewerby Land Train". Sewerby Hall & Gardens. East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "Bridlington Gets £150k Land Train Investment". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- "Bay Primary School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Burlington Junior School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Burlington Junior School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Hilderthorpe Primary School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Martongate Primary School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "New Pasture Lane Primary School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "St Mary's R C School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "New Pasture Lane Primary School". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington School Sports College". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Headlands School and Community Science College". Ofsted. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "East Riding College". Ofsted. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "GP practices in struggling town forced to re-open patient lists". Pulse. 25 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Single GP Building in Bridlington WON'T Go Ahead". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Historic England. "Christ Church (Grade II) (1281739)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Conerstone Church". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Bridlington Baptist Church". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Free Presbyterian Church". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Calvary Chapel by the Sea". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Methodist Church History in Bridlington". Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Roman Catholicism in Bridlington". Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Bridlington Town AFC

- "Bridlington Cricket Club". Bridlingtoncc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Kempton, Andrew (29 April 2013). "Bridlington RUFC". Pitchero.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Edwards, John (15 May 2019). "Bridlington Rugby Club and Wold Top Brewery win at Chairman's Awards". Bridlington Free Press. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Bridlington won but other results send them down". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 14 April 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "TWICKENHAM: A display the town should be proud of". Bridlington Free Press. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "History". Bridlington Hockey Club. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "BREAKING: Bridlington To Host Part of Tour De Yorkshire". Yorkshire Coast Radio. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "Tour de Yorkshire". East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- John, Taylor. "Newburgh, William of". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29470. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Worlingworth Local History Group – John Major". www.wlhg.org. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "BBC article on Benjamin Fawcett". BBC. 2003. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Henry Freeman". Whitby Museum. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "A. E.Matthews Filmography". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Fenby, Thomas". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com. A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U237173. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Warner, David (2011). The Yorkshire County Cricket Club: 2011 Yearbook (113th ed.). Ilkley, Yorkshire: Great Northern Books. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-905080-85-4.

- Worsley, Giles (7 October 1995). "Obituary; Francis Johnson – People, News". The Independent. London. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Selby, Michael (11 May 2006). "Obituary: Gordon Lakes". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Chilton, John, ed. (2004). Who's Who of British Jazz (2nd ed.). Continuum. p. 373. ISBN 0-8264-7234-6.

- "David Pinkney". Driver Database. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Andrew Dismore Web Page". Andrew Dismore. 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Mark Herman Filmography". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "The Biography of Angela Eagle". Angela Eagle. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- "Craig Short Central Defender". Toffee Web. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- "CNN Sports Illustrated". CNN. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Martini, Peter (8 January 2019). "Former fan favourite becomes odds-on favourite to be next York City manager". York Press. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Hutchins, L. J. (28 January 2009). "F1: Adam Khan gets a break with Renault". Brits on Pole. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- Foster, Alistair (20 March 2017). "Stranger Things star Charlie Heaton: I can relate to loner character". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Steve "Snips" Parson's reflection of Hull". Hull Echo. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Fleckney, Paul (17 August 2018). "Rosie Jones: 'People feel awkward about disability so I always have jokes in my back pocket'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Michael J, Curley. "John of Bridlington [St John of Bridlington, John Thwing]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14856. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bunyan, Nigel (29 August 2013). "David Hockney assistant died after drinking drain cleaner, inquest told". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Freeman, Sarah (18 February 2017). "So, just who is the real David Hockney?". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bridlington. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bridlington. |