Brian Eno

Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno, RDI (/ˈiːnoʊ/; born Brian Peter George Eno, 15 May 1948) is an English musician, record producer, visual artist, and theorist best known for his pioneering work in ambient music and contributions to rock, pop and electronic music.[1] A self-described "non-musician", Eno has helped introduce unique conceptual approaches and recording techniques to contemporary music.[1][2] He has been described as one of popular music's most influential and innovative figures.[1][3]

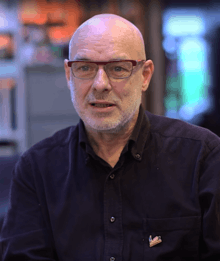

Brian Eno RDI | |

|---|---|

Eno in December 2015 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Brian Peter George Eno |

| Born | 15 May 1948 Melton, Suffolk, England |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1970–present |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | brian-eno |

Born in Suffolk, Eno studied painting and experimental music at the art school of Ipswich Civic College in the mid 1960s, and then at Winchester School of Art. He joined glam rock group Roxy Music as synthesiser player in 1971, recording two albums with the group. He departed in 1973 to record a number of solo albums, coining the term "ambient music" to describe his work on releases such as Another Green World (1975) and Music for Airports (1978). He also collaborated with artists such as Robert Fripp, Cluster, Harold Budd, David Bowie, and David Byrne, and produced albums by artists including John Cale, Jon Hassell, Laraaji, Talking Heads and Devo, and the no wave compilation No New York (1978). In subsequent decades, Eno has continued to record solo albums and work with artists including U2, Laurie Anderson, Grace Jones, Slowdive, Coldplay, James Blake, Kevin Shields, and Damon Albarn.

Dating back to his time as a student, Eno has also worked in other media, including sound installations and his mid-70s co-development of Oblique Strategies, a deck of cards featuring aphorisms intended to spur creative thinking. From the 1970s onwards, Eno's installations have included the sails of the Sydney Opera House in 2009[4] and the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank in 2016. An advocate of a range of humanitarian causes, Eno writes on a variety of subjects and is a founding member of the Long Now Foundation.[5] In 2019, Eno was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Roxy Music.[6]

Early life

Eno was born on 15 May 1948 at Phyllis Memorial Hospital in Melton, Suffolk, the son of Catholic parents William Arnold Eno (1916–1988),[7] who followed his father and grandfather into the postal service, and his Belgian wife Maria Alphonsine Eno (née Buslot; 1922–2005),[8] whom William had met during his service in World War II. The unusual surname Eno, long established in Suffolk, is thought to derive from the French Huguenot surname Hainault.[9] Maria already had a daughter (Brian's half-sister Rita), and together William and Maria would have two further children: Roger (born 1959) and Arlette (born 1961).[10]

Eno was educated at St Joseph's College, Ipswich, founded by the De La Salle Brothers order of Catholic brothers (from which on his confirmation he took the name St. John le Baptiste de la Salle).[11] Subsequently, Eno studied with new media artist Roy Ascott on the Groundcourse at the art school at Ipswich Civic College before going onto Winchester School of Art, from which he graduated in 1969.[12] At Winchester School of Art, Eno attended a lecture by Pete Townshend of The Who (also an ex-student of Roy Ascott) and cites that lecture as the moment he realised he could make music despite lacking a formal musical education.[13]

Whilst at school, Eno used a tape recorder as a musical instrument and experimented with his first, sometimes improvisational, bands. St. Joseph's College teacher and painter Tom Phillips encouraged him, recalling "Piano Tennis" with Eno, in which, after collecting pianos, they stripped and aligned them in a hall, striking them with tennis balls.[14] From that collaboration, he became involved in Cornelius Cardew's Scratch Orchestra. The first released recording in which Eno appears is the Deutsche Grammophon edition of Cardew's The Great Learning (recorded February 1971), as one of the voices in the recital of Paragraph 7 of The Great Learning. Another early recording was the Berlin Horse soundtrack, by Malcolm Le Grice, a nine-minute, 2 × 16mm-double-projection, released in 1970 and presented in 1971.[15]

Career

1970s

Eno's professional music career began in London when he became a founder member (1971–1973) of the glam/art rock band Roxy Music. Initially Eno did not appear on stage at their live shows, but operated the mixing desk, processing the band's sound with a VCS3 synthesiser and tape recorders, and singing backing vocals. He did, however, eventually appear on stage as a performing member of the group, usually flamboyantly costumed. He quit the band on completing the promotional tour for the band's second album, For Your Pleasure, because of disagreements with lead singer Bryan Ferry and boredom with the rock star life.[16]

In 1992, he described his Roxy Music tenure as important to his career: "As a result of going into a subway station and meeting [saxophonist Andy Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and, as a result of that, I have a career in music. If I'd walked ten yards further on the platform, or missed that train, or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now".[17] During his period with Roxy Music, and for his first three solo albums, he was credited on records only as 'Eno'.

Eno embarked on a solo career almost immediately. Between 1973 and 1977, he created four albums of electronically inflected art pop:[18] Here Come the Warm Jets (1973), Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (1974), Another Green World (1975), and Before and After Science (1977). Tiger Mountain contains the galloping "Third Uncle", one of Eno's best-known songs, owing in part to its later being covered by Bauhaus and 801. Critic Dave Thompson writes that the song is "a near punk attack of riffing guitars and clattering percussion, 'Third Uncle' could, in other hands, be a heavy metal anthem, albeit one whose lyrical content would tongue-tie the most slavish air guitarist."[19]

These four albums were remastered and reissued in 2004 by Virgin's Astralwerks label. Due to Eno's decision not to add any extra tracks of the original material, a handful of tracks originally issued as singles have not been reissued, including the single mix of "King's Lead Hat", the title of which is an anagram of "Talking Heads", whilst "Seven Deadly Finns" and "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" were included on the deleted Eno Box II: Vocal.

During this period, Eno also played three dates with Phil Manzanera in the band 801, a "supergroup" that performed more or less reworked selections from albums by Eno, Manzanera, and Quiet Sun, as well as covers of songs by The Beatles ("Tomorrow Never Knows") and The Kinks ("You Really Got Me").

In 1967, Eno developed a tape delay system. The technique involved two Revox tape recorders set up side by side, with the tape unspooling from the first deck being carried over to the second deck to be spooled. This enabled sound recorded on the first deck to be played back by the second deck at a time delay that varied with the distance between the two decks and the speed of the tape (typically a few seconds). Working with Robert Fripp (from King Crimson) the pair used this system in their collaboration (No Pussyfooting) (1973).[20] Subsequently, Fripp referred to this method as "Frippertronics". In 1975, Fripp and Eno released a second album, Evening Star, and played several live shows in Europe.

Eno was a prominent member of the performance art-classical orchestra the Portsmouth Sinfonia – having started playing clarinet with them in 1972. In 1973, he produced the orchestra's first album The Portsmouth Sinfonia Plays the Popular Classics (released in March 1974) and in 1974, he produced the live album Hallelujah! The Portsmouth Sinfonia Live at the Royal Albert Hall, a recording of their infamous May 1974 concert (released in October 1974). In addition to producing both albums, Eno performed in the orchestra on both recordings playing the clarinet. Eno also deployed the orchestra's famously dissonant string section on his second solo album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy). The orchestra at this time included other musicians whose solo work he would subsequently release on his Obscure label including Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman. That year he also composed music for the album Lady June's Linguistic Leprosy, with Kevin Ayers, to accompany the poet June Campbell Cramer.

Ambient music

Eno released a number of eclectic ambient electronic and acoustic albums. He coined the term "ambient music",[21] which is designed to modify the listener's perception of the surrounding environment. In the liner notes accompanying Ambient 1: Music for Airports, Eno wrote: "Ambient music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular, it must be as ignorable as it is interesting."[22]

Eno was hit by a taxi while crossing the street in January 1975 and spent several weeks recuperating at home. His girlfriend brought him an old record of harp music, which he lay down to listen to. He realized that he had set the amplifier to a very low volume, and one channel of the stereo was not working, but he lacked the energy to get up and correct it. "This presented what was for me a new way of hearing music – as part of the ambience of the environment just as the colour of the light and sound of the rain were parts of the ambience."[23]

Eno's first work of ambient music was Discreet Music (1975), again created with an elaborate tape-delay methodology which he diagrammed on the back cover of the LP; it is considered the landmark album of the genre. This was followed by his Ambient series: Music for Airports (Ambient 1), The Plateaux of Mirror (Ambient 2) featuring Harold Budd on keyboard, Day of Radiance (Ambient 3) with American composer Laraaji playing zither and hammered dulcimer, and On Land (Ambient 4)).

1980s

In 1980, Eno provided a film score for Herbert Vesely's Egon Schiele – Exzess und Bestrafung, also known as Egon Schiele – Excess and Punishment. The ambient-style score was an unusual choice for an historical piece, but it worked effectively with the film's themes of sexual obsession and death.

Before Eno made On Land, Robert Quine played him Miles Davis' "He Loved Him Madly" (1974). Eno stated in the liner notes for On Land, "Teo Macero's revolutionary production on that piece seemed to me to have the "spacious" quality I was after, and like Federico Fellini's 1973 film Amarcord, it too became a touchstone to which I returned frequently."[24]

In 1980 to 1981, during which time Eno travelled to Ghana for a festival of West African music, he was collaborating with David Byrne of Talking Heads. Their album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, was built around radio broadcasts Eno collected whilst living in the United States, along with sampled music recordings from around the world transposed over music predominantly inspired by African and Middle Eastern rhythms.

In 1983, Eno collaborated with his brother, Roger Eno, and Daniel Lanois on the album Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks that had been commissioned by Al Reinert for his film For All Mankind (1989).[25][26] Tracks from the album were subsequently used in several other films, including Trainspotting.[27]

1990s

In September 1992, Eno released Nerve Net, an album utilising heavily syncopated rhythms with contributions from several former collaborators including Fripp, Benmont Tench, Robert Quine and John Paul Jones. This album was a last-minute substitution for My Squelchy Life, which contained more pop oriented material, with Eno on vocals.[28] Several tracks from My Squelchy Life later appeared on 1993's retrospective box set Eno Box II: Vocals, and the entire album was eventually released in 2014 as part of an expanded re-release of Nerve Net. Eno also released The Shutov Assembly in 1992, recorded between 1985 and 1990. This album embraces atonality and abandons most conventional concepts of modes, scales and pitch. Emancipated from the constant attraction towards the tonic that underpins the Western tonal tradition, the gradually shifting music originally eschewed any conventional instrumentation, save for treated keyboards.[29]

During the 1990s, Eno worked increasingly with self-generating musical systems, the results of which he called generative music. This allows the listener to hear music that slowly unfolds in almost infinite non-repeating combinations of sound.[30] In one instance of generative music, Eno calculated that it would take almost 10,000 years to hear the entire possibilities of one individual piece. Eno achieves this through the blending of several independent musical tracks of varying length. Each track features different musical elements and in some cases, silence. When each individual track concludes, it starts again re-configuring differently with the other tracks. He has presented this music in his own art and sound installations and those in collaboration with other artists, including I Dormienti (The Sleepers), Lightness: Music for the Marble Palace, Music for Civic Recovery Centre, The Quiet Room, and Music for Prague.[31]

One of Eno's better-known collaborations was with the members of U2, Luciano Pavarotti and several other artists in a group called Passengers. They produced the 1995 album Original Soundtracks 1, which reached No. 76 on the US Billboard charts and No. 12 in the UK Albums Chart. It featured a single, "Miss Sarajevo", which reached number 6 in the UK Singles Chart.[32] This collaboration is chronicled in Eno's book A Year with Swollen Appendices, a diary published in 1996.

In 1996, Eno scored the six-part fantasy television series Neverwhere.[33]

2000s

In 2004, Fripp and Eno recorded another ambient music collaboration album, The Equatorial Stars.

Eno returned in June 2005 with Another Day on Earth, his first major album since Wrong Way Up (with John Cale) to prominently feature vocals (a trend he continued with Everything That Happens Will Happen Today). The album differs from his 1970s solo work due to the impact technological advances on musical production, evident in its semi-electronic production.

In early 2006, Eno collaborated with David Byrne again, for the reissue of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts in celebration of the influential album's 25th anniversary. Eight previously unreleased tracks recorded during the initial sessions in 1980/81, were added to the album.[34] An unusual interactive marketing strategy was employed for its re-release, the album's promotional website features the ability for anyone to officially and legally download the multi-tracks of two songs from the album, "A Secret Life" and "Help Me Somebody". This allowed listeners to remix and upload new mixes of these tracks to the website for others to listen and rate them.

In late 2006, Eno released 77 Million Paintings, a program of generative video and music specifically for home computers. As its title suggests, there is a possible combination of 77 million paintings where the viewer will see different combinations of video slides prepared by Eno each time the program is launched. Likewise, the accompanying music is generated by the program so that it's almost certain the listener will never hear the same arrangement twice. The second edition of "77 Million Paintings" featuring improved morphing and a further two layers of sound was released on 14 January 2008. In June 2007, when commissioned in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California, Annabeth Robinson (AngryBeth Shortbread) recreated 77 Million Paintings in Second Life.[35]

In 2007, Eno's music was featured in a movie adaption of Irvine Welsh's best-selling collection Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance. He also appeared playing keyboards in Voila, Belinda Carlisle's solo album sung entirely in French.

Also in 2007, Eno contributed a composition titled "Grafton Street" to Dido's third album, Safe Trip Home, released in November 2008.[36]

In 2008, he released Everything That Happens Will Happen Today with David Byrne, designed the sound for the video game Spore[37] and wrote a chapter to Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture, edited by Paul D. Miller (a.k.a. DJ Spooky).

In June 2009, Eno curated the Luminous Festival at Sydney Opera House, culminating in his first live appearance in many years. "Pure Scenius" consisted of three live improvised performances on the same day, featuring Eno, Australian improvisation trio The Necks, Karl Hyde from Underworld, electronic artist Jon Hopkins and guitarist Leo Abrahams.

Eno scored the music for Peter Jackson's film adaptation of The Lovely Bones, released in December 2009.[38]

2010s

Eno released another solo album on Warp in late 2010. Small Craft on a Milk Sea, made in association with long-time collaborators Leo Abrahams and Jon Hopkins, was released on 2 November in the United States and 15 November in the UK.[39] The album included five compositions [40] that were adaptions of those tracks that Eno wrote for The Lovely Bones.[41]

Eno also sang backing vocals on Anna Calvi's debut album, on the songs "Desire" and "Suzanne & I".[42] He later released Drums Between the Bells,[43] a collaboration with poet Rick Holland, on 4 July 2011.

In November 2012, Eno released Lux, a 76-minute composition in four sections, through Warp.[44]

Eno worked with French–Algerian Raï singer Rachid Taha on Taha's Tékitoi (2004) and Zoom (2013) albums, contributing percussion, bass, brass and vocals. Eno also performed with Taha at the Stop the War Coalition concert in London in 2005.[45]

In April 2014, Eno sang on, co-wrote, and co-produced Damon Albarn's Heavy Seas of Love, from his solo debut album Everyday Robots.[46]

In May 2014, Eno and Underworld's Karl Hyde released Someday World, featuring various guest musicians: from Coldplay's Will Champion and Roxy Music's Andy Mackay to newer names such as 22-year-old Fred Gibson, who helped produce the record with Eno.[47] Within weeks of that release, a second full-length album was announced titled High Life. This was released on 30 June 2014.[48]

In January 2016, a new Eno ambient soundscape was premiered as part of Michael Benson's planetary photography exhibition "Otherworlds" in the Jerwood Gallery of London's Natural History Museum. In a statement Eno commented on the unnamed half-hour piece:

"We can't experience space directly; those few who've been out there have done so inside precarious cocoons. They float in silence, for space has no air, nothing to vibrate – and therefore no sound. Nonetheless we can't resist imagining space as a sonic experience, translating our feelings about it into music. In the past we saw the universe as a perfect, divine creation – logical, finite, deterministic – and our art reflected that. The discoveries of the Space age have revealed instead a chaotic, unstable and vibrant reality, constantly changing. This music tries to reflect that new understanding."

The Ship, an album with music from Eno's installation of the same name was released on 29 April 2016 on Warp.[49]

In September 2016, the Portuguese synthpop band The Gift, released a single entitled Love Without Violins. As well as singing on the track, Eno co-wrote and produced it. The single was released on the band's own record label La Folie Records on 30 September.[50]

Eno's Reflection, an album of ambient, generative music, was released on Warp Records on 1 January. 2017. It was nominated for a Grammy Award for 2018's 60th. Grammy awards ceremony.[51][52]

In 2019, Eno participated in DAU, an immersive art and cultural installation in Paris by Russian film director Ilya Khrzhanovsky evoking life under Soviet authoritarian rule. Eno contributed six auditory ambiances.[53]

2020s

In March 2020, Eno and his brother, Roger Eno, released their collaborative album Mixing Colours.[54]

Record producer

From the beginning of his solo career in 1973, Eno was in demand as a record producer. The first album with Eno credited as producer was Lucky Leif and the Longships by Robert Calvert. Eno's lengthy string of producer credits includes albums for Talking Heads, U2, Devo, Ultravox and James. He also produced part of the 1993 album When I Was a Boy by Jane Siberry. He won the best producer award at the 1994 and 1996 BRIT Awards.

Eno describes himself as a "non-musician", using the term "treatments" to describe his modification of the sound of musical instruments, and to separate his role from that of the traditional instrumentalist. His skill at using "The Studio as a Compositional Tool"[55] (the title of an essay by Eno) led in part to his career as a producer. His methods were recognised at the time (mid-1970s) as unique, so much so that on Genesis's The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, he is credited with 'Enossification'; on Robert Wyatt's Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard with a Direct inject anti-jazz raygun and on John Cale's Island albums as simply being "Eno".

Eno has contributed to recordings by artists as varied as Nico, Robert Calvert, Genesis, David Bowie, and Zvuki Mu, in various capacities such as use of his studio/synthesiser/electronic treatments, vocals, guitar, bass guitar, and as just being 'Eno'. In 1984, he (amongst others) composed and performed the "Prophecy Theme" for the David Lynch film Dune; the rest of the soundtrack was composed and performed by the group Toto. Eno produced performance artist Laurie Anderson's Bright Red album, and also composed for it. The work is avant-garde spoken word with haunting and magnifying sounds. Eno played on David Byrne's musical score for The Catherine Wheel, a project commissioned by Twyla Tharp to accompany her Broadway dance project of the same name.

He worked with Bowie as a writer and musician on Bowie's influential 1977–79 'Berlin Trilogy' of albums, Low, "Heroes" and Lodger, on Bowie's later album Outside, and on the song "I'm Afraid of Americans". Recorded in France and Germany, the spacey effects on Low were largely created by Eno, who played a portable EMS Synthi A synthesizer. Producer Tony Visconti used an Eventide Harmonizer to alter the sound of the drums, claiming that the audio processor "f–s with the fabric of time."[56] After Bowie died in early 2016, Eno said that he and Bowie had been talking about taking Outside, the last album they'd worked on together, "somewhere new", and expressed regret that they wouldn't be able to pursue the project.[57]

Eno co-produced The Unforgettable Fire (1984), The Joshua Tree (1987), Achtung Baby (1991), and All That You Can't Leave Behind (2000) for U2 with his frequent collaborator Daniel Lanois, and produced 1993's Zooropa with Mark "Flood" Ellis. In 1995, U2 and Eno joined forces to create the album Original Soundtracks 1 under the group name Passengers; songs from which included "Your Blue Room" and "Miss Sarajevo". Even though films are listed and described for each song, all but three are bogus. Eno also produced Laid (1993), Wah Wah (1994) Millionaires (1999) and Pleased to Meet You (2001) for James, performing as an extra musician on all four. He is credited for "frequent interference and occasional co-production" on their 1997 album Whiplash.

Eno played on the 1986 album Measure for Measure by Australian band Icehouse. He remixed two tracks for Depeche Mode, "I Feel You" and "In Your Room", both single releases from the album Songs of Faith and Devotion in 1993. In 1995, Eno provided one of several remixes of "Protection" by Massive Attack (originally from their Protection album) for release as a single.

In 2007, he produced the fourth studio album by Coldplay, Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends, released in 2008. Also in 2008, he worked with Grace Jones on her album Hurricane, credited for "production consultation" and as a member of the band, playing keyboards, treatments and background vocals. He worked on the twelfth studio album by U2, again with Lanois, titled No Line on the Horizon. It was recorded in Morocco, the South of France and Dublin and released in Europe on 27 February 2009.

In 2011, Eno and Coldplay reunited and Eno contributed "enoxification" and additional composition on Coldplay's fifth studio album Mylo Xyloto, released on 24 October of that year.

The Microsoft Sound

In 1994, Microsoft designers Mark Malamud and Erik Gavriluk approached Eno to compose music for the Windows 95 project.[58] The result was the six-second start-up music-sound of the Windows 95 operating system, "The Microsoft Sound". In an interview with Joel Selvin in the San Francisco Chronicle he said:

The idea came up at the time when I was completely bereft of ideas. I'd been working on my own music for a while and was quite lost, actually. And I really appreciated someone coming along and saying, "Here's a specific problem – solve it."

The thing from the agency said, "We want a piece of music that is inspiring, universal, blah-blah, da-da-da, optimistic, futuristic, sentimental, emotional," this whole list of adjectives, and then at the bottom it said "and it must be 3 1⁄4 seconds long."[† 1]

I thought this was so funny and an amazing thought to actually try to make a little piece of music. It's like making a tiny little jewel.

In fact, I made eighty-four pieces. I got completely into this world of tiny, tiny little pieces of music. I was so sensitive to microseconds at the end of this that it really broke a logjam in my own work. Then when I'd finished that and I went back to working with pieces that were like three minutes long, it seemed like oceans of time.[59]

Eno shed further light on the composition of the sound on the BBC Radio 4 show The Museum of Curiosity, admitting that he created it using a Macintosh computer, stating "I wrote it on a Mac. I've never used a PC in my life; I don't like them."[60]

Video work

Eno has spoken of an early and ongoing interest in exploring light in a similar way to his work with sound. He started experimenting with the medium of video in 1978. Eno describes the first video camera he received, which would initially become his main tool for creating ambient video and light installations:

"One afternoon while I was working in the studio with Talking Heads, the roadie from Foreigner, working in an adjacent studio, came in and asked whether anyone wanted to buy some video equipment. I'd never really thought much about video, and found most 'video art' completely unmemorable, but the prospect of actually owning a video camera was, at that time, quite exotic."[61]

The Panasonic industrial camera Eno received had significant design flaws preventing the camera from sitting upright without the assistance of a tripod. This led to his works being filmed in vertical format, requiring the television set to be flipped on its side to view it in the proper orientation.[62] The pieces Eno produced with this method, such as Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan (1980) and Thursday Afternoon (1984) (accompanied by the album of the same title), were labelled as 'Video Paintings.' He explained the genre title in the music magazine NME:

"I was delighted to find this other way of using video because at last here's video which draws from another source, which is painting ... I call them 'video paintings' because if you say to people 'I make videos', they think of Sting's new rock video or some really boring, grimy 'Video Art'. It's just a way of saying, 'I make videos that don't move very fast."[63]

These works presented Eno with the opportunity to expand his ambient aesthetic into a visual form, manipulating the medium of video to produce something not present in the normal television experience. His video works were shown around the world in exhibitions in New York and Tokyo, as well as released on the compilation 14 Video Paintings in 2005.[64]

Eno continued his video experimentation through the 80s, 90s and 2000s, leading to further experimentation with the television as a malleable light source and informing his generative works such as 77 Million Paintings in 2006.[65]

Generative music

Eno gives the example of wind chimes. He says that these systems and the creation of them have been a focus of his since he was a student: "I got interested in the idea of music that could make itself, in a sense, in the mid 1960s really, when I first heard composers like Terry Riley, and when I first started playing with tape recorders." [66]

Initially Eno began to experiment with tape loops to create generative music systems. With the advent of CDs he developed systems to make music of indeterminate duration using several discs of material that he'd specifically recorded so that they would work together musically when driven by random playback.

In 1995, he began working with the company Intermorphic to create generative music through utilising programmed algorithms. The collaboration with Intermorphic led Eno to release Generative Music 1 - which requires Intermorphic's Koan Player software for PC. The Koan software made it possible for generative music to be experienced in the domestic environment for the first time.

Generative Music 1

In 1996, Eno collaborated in developing the SSEYO Koan generative music software system (by Pete Cole and Tim Cole of Intermorphic) that he used in composing Generative Music 1—only playable on the Koan generative music system. Further music releases using Koan software include: Wander (2001) and Dark Symphony (2007)—both include works by Eno, and those of other artists (including SSEYO's Tim Cole).

Released excerpts

Eno started to release excerpts of results from his 'generative music' systems as early as 1975 with the album Discreet Music. Then again in 1978 with Music for Airports:

Music for Airports, at least one of the pieces on there, is structurally very, very simple. There are sung notes, sung by three women and my self. One of the notes repeats every 23 1/2 seconds. It is in fact a long [recorded tape] loop running around a series of tubular aluminum chairs in Conny Plank's studio. The next lowest loop repeats every 25 7/8 seconds or something like that. The third one every 29 15/16 seconds or something. What I mean is they all repeat in cycles that are called incommensurable – they are not likely to come back into sync again. So this is the piece moving along in time. Your experience of the piece of course is a moment in time, there. So as the piece progresses, what you hear are the various clusterings and configurations of these six basic elements. The basic elements in that particular piece never change. They stay the same. But the piece does appear to have quite a lot of variety. In fact it's about eight minutes long on that record, but I did have a thirty minute version which I would bore friends who would listen to it. The thing about pieces like this of course is that they are actually of almost infinite length if the numbers involved are complex enough. They simply don't ever re-configure in the same way again. This is music for free in a sense. The considerations that are important, then, become questions of how the system works and most important of all what you feed into the system.

— Brian Eno, Generative Music: A talk delivered in San Francisco, June 8, 1996[67]

The list below consists of albums, soundtracks and downloadable files that contain excerpts from some of Eno's generative music explorations:

- 1970 – Berlin Horse [Film Short]

- 1975 – Discreet Music

- 1975 – Evening Star (Fripp & Eno)

- 1978 – Ambient 1: Music For Airports

- 1981 – Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan [Installation Video]

- 1982 – Ambient 4: On Land

- 1983 – Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks (Eno, Lanois & R Eno)

- 1983 – Music For Films II (Eno, Lanois & R Eno) [exclusive to 'Working Backwards' Box Set]

- 1984 – Thursday Afternoon [Installation Video]

- 1985 – Thursday Afternoon

- 1988 – Music For Films III (Various Artists)

- 1989 – Textures (Eno, Lanois & R Eno)

- 1989 – For All Mankind [Documentary Soundtrack]

- 1992 – The Shutov Assembly

- 1993 – Neroli (Thinking Music Part IV)

- 1994 – Glitterbug [Original Soundtrack]

- 1996 – Neverwhere [BBC TV Mini-Series Soundtrack]

- 1997 – Contra 1.2

- 1997 – Lightness

- 1998 – Music for Prague

- 1999 – I Dormienti

- 1999 – Kite Stories

- 2000 – Music For Civic Recovery Centre

- 2001 – Compact Forest Proposal

- 2003 – Curiosities – Volume I

- 2004 – Curiosities – Volume II

- 2012 – Lux

- 2013 – CAM [Web – the book 'Brian Eno: Visual Music' includes a Download Code]

- 2014 – The Shutov Bonus Material ['Shutov Assembly' Bonus CD]

- 2014 – New Space Music ['Neroli' Bonus CD]

- 2016 – The Ship

- 2016 – Reflection

- 2017 – Sisters [Web Download]

- 2018 – Music for Installations [Box Set][68]

Several of the released excerpts (listed above) originated as, or are derivative of, soundtracks Eno created for art installations. Most notably The Shutov Assembly (view breakdown of Album's sources), Contra 1.2 thru to Compact Forest Proposal, Lux, CAM, and The Ship.

Installations

Eno has created installations combining artworks and sound that have shown across the world since 1979, beginning with 2 Fifth Avenue and White Fence, in the Kitchen Centre, New York, NY.[69] Typically Eno's installations feature light as a medium explored in multi-screen configurations, and music that is created to blur the boundaries between itself and its surroundings:

"There is a sharp distinction between "music" and "noise", just as there is a distinction between the musician and the audience. I like blurring those distinctions – I like to work with all the complex sounds on the way out to the horizon, to pure noise, like the hum of London." [70] With each installation Eno's music and artworks interrogate the visitors' perception of space and time within a seductive, immersive environment.[71][72]

Since his experiments with sound as an art student using reel to reel tape recorders,[73] - and in art employing the medium of light,[74] Eno has utilised breakthroughs in technology to develop 'processes rather than final objects', processes that in themselves have to "jolt your senses," have "got to be seductive."[75] Once set in motion these processes produce potentially un-ending and continuous, non-repeating music and artworks that Eno, though the artist, could not have imagined;[76] and with them he creates the slowly unfolding immersive environments of his installations.

David A. Ross writes in the programme notes to Matrix 44 in 1981: "In a series of painterly video installations first shown in 1979, Eno explored the notion of environmental ambiance. Eno proposes a use for music and video that is antithetical to behavior control-oriented "Muzak" in that it induces and invites the viewer to enter a meditative, detached state, rather than serve as an operant conditioner for work-force efficiency. His underlying strategy is to create works which provide natural levels of variety and redundancy which bring attention to, rather than mimic, essential characteristics of the natural environment. Eno echoes Matisse's stated desire that his art serve as an armchair for the weary businessman."[77]

Early installations benefitted from breakthroughs in video technology that inspired Eno to use the TV screen as a monitor and enabled him to experiment with the opposite of the fast-moving narratives typical of TV to create evolving images with an almost imperceptible rate of change. "2 Fifth Avenue", ("a linear four-screen installation with music from Music For Airports") resulted from Eno shooting "the view from his apartment window: without ... intervention," recording "what was in front of the camera for an unspecified period of time ... In a simple but crude form of experimental post production, the colour controls of the monitors on which the work was shown were adjusted to wash out the picture, producing a high-contrast black and white image in which colour appeared only in the darkest areas. ... Eno manipulated colour as though painting, observing: 'video for me is a way of configuring light, just as painting is a way of configuring paint.'"[78]

From the outset, Eno's video works, were "more in the sphere of paintings than of cinema".[79] The author and artist John Coulthart called Mistaken Memories of Medieval Manhattan (1980–81), which incorporated music from Ambient 4: On Land, "The first ambient film." He explains: "Eno filmed several static views of New York and its drifting cloudscape from his thirteenth-floor apartment in 1980–81. The low-grade equipment ... give[s] the images a hazy, impressionistic quality. Lack of a tripod meant filming with the camera lying on its side so the tape had to be re-viewed with a television monitor also turned on its side."[80] And turning the TV on its side, says David A. Ross, "recontextualize[d] the television set, and ... subliminally shift[ed] the way the video image represents recognizable realities ... Natural phenomena like rain look quite different in this orientation; less familiar but curiously more real." [81]

Thursday Afternoon was a return to using figurative form, for Eno had by now begun "to think that I could use my TVs as light sources rather than as image sources. ... TV was actually the most controllable light source that had ever been invented – because you could precisely specify the movement and behaviour of several million points of coloured light on a surface. The fact that this prodigious possibility had almost exclusively been used to reproduce figurative images in the service of narratives pointed to evolution of the medium from the theatre and cinema. What I thought was that this machine, which pumped out highly controllable light, was actually the first synthesizer, and that its use as an imager-retailer represented a subset of its possible range." [82]

Turning the TV on its back, Eno played video colour fields of differing lengths of time that would slowly re-combine in different configurations. Placing ziggurats (3 dimensional constructions) of different lengths and sizes on top of the screens that defined each separate colour field, these served to project the internal light source upward. "The light from it was tangible as though caught in a cloud of vapour. Its slowly changing hues and striking colour collisions were addictive. We sat watching for ages, transfixed by this totally new experience of light as a physical presence."[83]

Calling these light sculptures Crystals (first shown in Boston in 1983), Eno further developed them for the Pictures of Venice exhibition at Gabriella Cardazzo's Cavallino Gallery (Venice,1985). Placing plexiglass on top of the structures he found that these further diffused the light so the shapes outlined through this surface appeared to be described differently in the slowly changing fields of light.[84]

By positioning sound sources in different places and different heights in the exhibition room Eno intended that the music would be something listened to from the inside rather than the outside. For the I Dormienti show in 1999 that featured sculptures of sleeping figures by Mimmo Paladino in the middle of the circular room, Eno placed speakers in each of the 12 tunnels running from it.

Envisioning the speakers themselves as instruments, led to Eno's 'speaker flowers' becoming a feature of many installations, including at the Museo dell' Ara Pacis (Rome, 2008), again with Mimmo Paladino and 'Speaker Flowers and Lightboxes' at Castello Svevo in Trani (Italy 2017). Re-imagining the speaker as a flower with a voice that could be heard as it moved in the breeze, he made 'bunches' of them, "sculptural objects [that] ... consist of tiny chassis speakers attached to tall metal stands that sway in response to the sound they emit."[85] The first version of these were shown at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam(1984).

Since On Land (1982), Eno has sought to blur the boundaries between music and non-music and incorporates environmental sounds into his work. He treats synthesised and recorded sounds for specific effects.[86]

In the antithesis of 20th century shock art, Eno's works create environments that are: "Envisioned as extensions of everyday life while offering a refuge from its stresses."[87] Creating a space to reflect was a stated aim in Eno's Quiet Club series of installations that have shown across the world, and include Music for Civic Recovery Centre at the David Toop curated Sonic Boom festival at the Hayward Gallery in 2000.

The Quiet Club series (1986-2001) grew from Eno's site-specific installations that included the Place series (1985-1989). These also featured light sculptures and audio with the addition of conventional materials, such as "tree trunks, fish bowls, ladders, rocks". Eno used these in unconventional ways to create new and unexpected experiences and modes of engagements, offering an extension of and refuge from, everyday life.[88]

The continually flowing non-repeating music and art of Eno's installations mitigate against habituation to the work and maintain the visitors' engagement with it. "One of the things I enjoy about my shows is...lots of people sitting quietly watching something that has no story, few recognisable images and changes very slowly. It's somewhere between the experience of painting, cinema, music and meditation...I dispute the assumption that everyone's attention span is getting shorter: I find people are begging for experiences that are longer and slower, less "dramatic" and more sensual." [89] Tanya Zimbardo writing on New Urban Spaces Series 4. "Compact Forest Proposal" for SF MOMA (2001) confirms: "During the first presentation of this work, as part of the exhibition 010101: Art in Technological Times at SFMOMA in 2001, visitors often spent considerable time in this dreamlike space."[90]

In Eno's work, both art and music are released from their normal constraints. The music set up to randomly reconfigure is modal and abstract rather than tonal, and so the listener is freed from expectations set up by Western tonal harmonic conventions.[91] The artworks in their continual slowly shifting combinations of colour (and in the case of 77 Million Paintings image re-configurations) themselves offer a continually engaging immersive experience through their unfolding fields of light.

77 Million Paintings

Developments in computer technology meant that the experience of Eno's unending non-repeatable generative art and music was no longer only possible in the public spaces of his exhibitions. With software developer and programmer Jake Dowie, Eno created a generative art/music installation '77 Million Paintings' for the domestic environment. Developed for both PC and Mac, the process is explained by Nick Robertson in the accompanying booklet. "One way to approach this idea is to imagine that you have a large box full of painted components and you are allowed to blindly take out between one and four of these at any time and overlay them to make a complete painting. The selection of the elements and their duration in the painting is variable and arbitrarily determined…" [92]

Most (nearly all) of the visual 'elements' were hand-painted by Eno onto glass slides, creating an organic heart to the work. Some of the slides had formed his earlier 'Natural Selections' exhibition projected onto the windows of the Triennale in Milan. (1990). This exhibition marked the beginning of Eno's site specific installations that re-defined spaces on a large scale.[93]

For the Triennale exhibition, Eno with Rolf Engel and Roland Blum at Atelier Marktgraph, used new 'dataton' technology that could be programmed to control the fade up and out times of the light sources.[94] But, unlike the software developed for '77 Million', this was clumsy and limited the practical realisation of Eno's vision.

With the computer programmed to randomly select a combination of up to four images of different durations, the on screen painting continually reconfigures as each image slowly dissolves whilst another appears. The painting will be different for every viewer in every situation, uniquely defining each moment. Eno likens his role in creating this piece to one of a gardener planting seeds. And like a gardener he watches to see how they grow, waiting to see if further intervention is necessary.[95] In the liner notes Nick Robertson explains: "Every user will buy exactly the same pack of 'seeds' but they will all grow in different ways and into distinct paintings, the vast majority of which, the artist himself has not even seen. …The original in art is no longer solely bound up in the physical object, but rather in the way the piece lives and grows."[92]

Although designed for the domestic environment, 77 million paintings has been (and continues to be) exhibited in multi-screen installations across the world. It has also been projected onto architectural structures, including the sails of the Sydney Opera House (2009), Carioca Aqueduct (The Arcos Di Lapa) Brazil (2012) and the giant Lovell Telescope at the Jodrell Bank Observatory (2016). During an exhibition at Fabrica Brighton, (2010) the orthopaedic surgeon Robin Turner noticed the calming effect the work had on the visitors. Turner asked Eno to provide a version for the Montefiore hospital in Hove. Since then 77 Million and Eno's latest "Light Boxes" have been commissioned for use in hospitals.

Montefiore Hospital Installations

In 2013, Eno created two permanent light and sound installations at Montefiore Hospital in Hove, East Sussex, England.[96] In the hospital's reception area "77 Million Paintings for Montefiore" consists of eight plasma monitors mounted on the wall in a diagonally radiating flower-like pattern. They display an evolving collage of coloured patterns and shapes whilst Eno's generative ambient music plays discreetly in the background. The other aptly named "Quiet Room for Montefiore" (available for patients, visitors and staff) is a space set apart for meditative reflection. It is a moderately sized room with three large panels displaying dissolves of subtle colours in patterns that are reminiscent of Mondrian paintings. The environment brings Eno's ambient music into focus and facilitates the visitors' cognitive drift, freeing them to contemplate or relax.

Spore

Eno composed most of the music for the Electronic Arts video game Spore (2008), assisted by his long-term collaborator, the musician and programmer Peter Chilvers. Much of the music is generative and responsive to the player's position within the game.

iOS apps

Inspired by possibilities presented to Eno and Peter Chilvers whilst working together on the generative soundtrack for the video game Spore (2008), the two began to release generative music in the Apple App format. They set up the website generativemusic.com and created generative music applications for the iPhone, iPod Touch, and iPad:

- 2008 – Bloom

- 2009 – Trope

- 2012 – Scape

- 2016 – Reflection

In 2009, Peter Chilvers and Sandra O'Neill also created an App entitled Air (released through generativemusic.com as well) – based on concepts developed by Eno in his Ambient 1: Music for Airports album.[97]

Reflection

The generative version of Reflection is the fourth iOS App created by Brian Eno and Peter Chilvers: of generativemusic.com. Unlike other Apps they released Reflection provides no real options other than Play/Pause – later, in its initial update, Airplay and Sleep Timer options were added. As Apple had started increasing prices for Apps sold in UK, they lowered its price. For those who'd bought the app at a higher price, Eno and Chilvers provided links to a free download of a four track album called 'Sisters' (each track with a 15:14 duration). The following appears on the app's Apple iTunes page:

As a result of the Brexit-related fall in value of the British pound Apple have increased the prices of all apps sold in the UK by 25%. While we always intended REFLECTION to be a premium priced app, we feel this increase makes it too expensive, so we will take the hit in order to keep the British price to the consumer at its original level.

In other territories this decision will translate into a reduced price for the app.

As a thank you to everyone who has supported the REFLECTION app, we are adding a free surprise downloadable gift to it for a limited time. To access it, simply update REFLECTION in the App Store and follow the instructions when you open the app on your device. The download will be available until 28th February [2017].[98] and the App's Apples iTunes page[99]

Previous to the updates for the App, the iTunes page used the following from Eno.

Reflection is the most recent of my Ambient experiments and represents the most sophisticated of them so far.

My original intention with Ambient music was to make endless music, music that would be there as long as you wanted it to be. I wanted also that this music would unfold differently all the time – 'like sitting by a river': it's always the same river, but it's always changing. But recordings – whether vinyl, cassette or CD – are limited in length, and replay identically each time you listen to them. So in the past I was limited to making the systems which make the music, but then recording 30 minutes or an hour and releasing that. Reflection in its album form – on vinyl or CD – is like this. But the app by which Reflection is produced is not restricted: it creates an endless and endlessly changing version of the piece of music.

The creation of a piece of music like this falls into three stages: the first is the selection of sonic materials and a musical mode – a constellation of musical relationships. These are then patterned and explored by a system of algorithms which vary and permutate the initial elements I feed into them, resulting in a constantly morphing stream (or river) of music. The third stage is listening. Once I have the system up and running I spend a long time – many days and weeks in fact – seeing what it does and fine-tuning the materials and sets of rules that run the algorithms. It's a lot like gardening: you plant the seeds and then you keep tending to them until you get a garden you like.[100]

The version of Reflection available on the fixed formats (CD, Vinyl and download File) consists of two (joined) excerpts from the Reflection app. This was revealed in Brian's interview with Philip Sherburne:

[Philip Sherburne] Given the infinite nature of the Reflection project, was it difficult to select the 54-minute chunk that became the album?

[Brian Eno] Yes, it was quite interesting doing that. When you're running it as an ephemeral piece, you have quite different considerations. If there is something that is a bit doubtful or odd, you think, OK, that's just in the nature of the piece and now it's passed and we're somewhere else. Whereas if you're thinking of it as a record that people are going to listen to again and again, what philosophy do you take? Choose just a random amount of time? Could have done that. Just do several of them and fix them together? Is that faking it? These are very interesting philosophical questions.

[Philip Sherburne] Which approach did you follow?

[Brian Eno] A hybrid approach. I generated 11 pieces of the length I'd set the piece to be and I had them all in my iTunes on random shuffle, so I would be listening at night, doing other things, and as one ran through, I would think, That was a nice one, I particularly like the second half. So then I would make a note. I did this for quite a few evenings. There were two that I really liked. On one, the last 40 minutes of it were lovely, and on another, the first 25 minutes of it were really nice. So I thought, This is a studio, I'm making a record. I'll edit them together! It was like the birth of rock'n'roll. I'm allowed to do that! It's not cheating. It was quite a bit of jiggery-pokery to find a place I could do it, but the result is two pieces stuck together.

— Philip Sherburne / Brian Eno, A Conversation With Brian Eno About Ambient Music[101]

Artworks: Light Boxes

Eno's "light boxes" utilise advances in LED technology that has enabled him to re-imagine his ziggurat light paintings - and early light boxes as featured in Kite Stories (1999) - for the domestic environment. The light boxes feature slowly changing combinations of colour fields that draw attention differently to the shapes outlined by delineating structures within. As the paintings slowly evolve each passing moment is defined differently, drawing the viewer's focus into the present moment. The writer and cultural essayist Michael Bracewell writes that the viewer "is also encouraged to engage with a generative sensor/aesthetic experience that reflects the ever-changing moods and randomness of life itself". He likens Eno's art to "Matisse or Rothko at their most enfolding." [102]

First shown commercially at the Paul Stolper Gallery in London (forming the Light Music exhibition in 2016 that included lenticular paintings by Eno),[103] 'light boxes' have been shown across the world. They remain in permanent display in both private and public spaces. Recognised for their therapeutic contemplative benefits, Eno's 'light paintings' have been commissioned for specially dedicated places of reflection including in Chelsea and Westminster hospital, the Montefiore Hospital in Hove and a three and a half metre lightbox for the sanctuary room in the Macmillan Horizon Centre in Brighton.

Obscure Records

Eno started the Obscure Records label in Britain in 1975 to release works by lesser-known composers. The first group of three releases included his own composition, Discreet Music, and the now-famous The Sinking of the Titanic (1969) and Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet (1971) by Gavin Bryars. The second side of Discreet Music consisted of several versions of Pachelbel's Canon, the composition which Eno had previously chosen to precede Roxy Music's appearances on stage and to which he applied various algorithmic transformations, rendering it almost unrecognisable. Side one consisted of a tape loop system for generating music from relatively sparse input. These tapes had previously been used as backgrounds in some of his collaborations with Fripp, most notably on Evening Star. Ten albums were released on Obscure, including works by John Adams, Michael Nyman, and John Cage.

Other work

In 1995, Eno travelled with Edinburgh University's Professor Nigel Osborne to Bosnia in the aftermath of the Bosnian War, to work with war-traumatised children, many of whom had been orphaned in the conflict. Osborne and Eno led music therapy projects run by Warchild in Mostar, at the Pavarotti centre, Bosnia 1995.[104]

Eno appeared as Father Brian Eno at the "It's Great Being a Priest!" convention, in "Going to America", the final episode of the television sitcom Father Ted, which originally aired on 1 May 1998 on Channel 4.[105]

In March 2008, Eno collaborated with the Italian artist Mimmo Paladino on a show of the latter's works with Eno's soundscapes at Ara Pacis in Rome, and in 2011, he joined Stephen Deazley and Edinburgh University music lecturer Martin Parker in an Icebreaker concert at Glasgow City Halls, heralded as a "long-awaited clash".[106]

In 2013, Eno sold limited edition prints of artwork from his 2012 album Lux from his website.[107][108]

In 2016, Eno was added to Edinburgh University's roll of honour[109] and in 2017, he delivered the Andrew Carnegie Lecture at the university.[110][111][112]

Eno continues to be active in other artistic fields. His sound installations have been exhibited in many prestigious venues around the world, including the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York; Vancouver Art Gallery, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, Baltic Art Centre, Gateshead, and the Sydney, São Paulo, and Venice Biennials.

Awards and honors

Asteroid 81948 Eno, discovered by Marc Buie at Cerro Tololo in 2000, was named in his honor.[113] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 18 May 2019 (M.P.C. 114955).[114]

In 2019, he was awarded Starmus Festival's Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication for Music & Arts.[115][116][117]

Influence

Eno is frequently referred to as one of popular music's most influential artists.[118] Producer and film composer Jon Brion has said: "I think he's the most influential artist since the Beatles."[119] Critic Jason Ankeny at AllMusic argues that Eno "forever altered the ways in which music is approached, composed, performed, and perceived, and everything from punk to techno to new age bears his unmistakable influence."[1] Eno has spread his techniques and theories primarily through his production; his distinctive style informed a number of projects in which he has been involved, including Bowie's "Berlin Trilogy" (helping to popularize minimalism) and the albums he produced for Talking Heads (incorporating, on Eno's advice, African music and polyrhythms), Devo, and other groups.[120] Eno's first collaboration with David Byrne, 1981's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, pioneered sampling techniques that would prove to be influential in hip-hop, and broke ground by incorporating world music into popular Western music forms.[121][122] Eno and Peter Schmidt's Oblique Strategies have been used by many bands, and Eno's production style has proven influential in several general respects: "his recording techniques have helped change the way that modern musicians;– particularly electronic musicians;– view the studio. No longer is it just a passive medium through which they communicate their ideas but itself a new instrument with seemingly endless possibilities."[123]

Whilst inspired by the ideas of minimalist composers including John Cage, Terry Riley and Erik Satie,[124] Eno coined the term ambient music to describe his own work and defined the term. The Ambient Music Guide states that he has brought from "relative obscurity into the popular consciousness" fundamental ideas about ambient music, including "the idea of modern music as subtle atmosphere, as chill-out, as impressionistic, as something that creates space for quiet reflection or relaxation."[123] His groundbreaking work in electronic music has been said to have brought widespread attention to and innovations in the role of electronic technology in recording.[124] Pink Floyd keyboardist Rick Wright said he "often eulogised" Eno's abilities.[125]

Eno's "unconventional studio predilections", in common with those of Peter Gabriel, were an influence on the recording of "In the Air Tonight", the single which launched the solo career of Eno's former drummer Phil Collins.[126] Collins said he "learned a lot" from working with Eno.[127] Both Half Man Half Biscuit (in the song "Eno Collaboration" on the EP of the same name) and MGMT have written songs about Eno. LCD Soundsystem has frequently cited Eno as a key influence. The Icelandic singer Björk also credited Eno as a major influence.[128]

Mora sti Fotia (Babies on Fire), one of the most influential Greek rock bands, was named after Eno's song "Baby's on Fire".[129]

In 2011, Belgian academics from the Royal Museum for Central Africa named a species of Afrotropical spider Pseudocorinna brianeno in his honour.[130]

In September 2016, asked by the website Just Six Degrees to name a currently influential artist, Eno cited the conceptual, video and installation artist Jeremy Deller as a source of current inspiration: "Deller's work is often technically very ambitious, involving organising large groups of volunteers and helpers, but he himself is almost invisible in the end result. I'm inspired by this quietly subversive way of being an artist, setting up situations and then letting them play out. To me it's a form of social generative art where the 'generators' are people and their experiences, and where the role of the artist is to create a context within which they collide and create."[131]

Personal life

In 1967, at the age of 18, Eno married Sarah Grenville. They had a daughter, Hannah (born July 1967), before divorcing. Eno married his manager Anthea Norman-Taylor in 1988, they have two daughters, Irial and Darla.[132]

Eno has referred to himself as "kind of an evangelical atheist" but has also professed an interest in religion.[133] In 1996, Eno and others started the Long Now Foundation to educate the public about the very long-term future of society and to encourage long-term thinking in the exploration of enduring solutions to global issues.[134]

The Nokia 8800 Sirocco Edition mobile phone features exclusive music composed by Eno.[135] Between 8 January 2007 and 12 February 2007, ten units of Nokia 8800 Sirocco Brian Eno Signature Edition mobile phones, individually numbered and engraved with Eno's signature, were auctioned off. All proceeds went to two charities chosen by Eno: the Keiskamma AIDS treatment program and the World Land Trust.[136]

In 1991, Eno appeared on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs. His chosen book was Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity by Richard Rorty and his luxury item was a radio telescope.[137]

Politics

In 2007, Eno joined the Liberal Democrats as youth adviser under Nick Clegg.[138]

Eno is now a member of the Labour Party.[139] In August 2015, he endorsed Jeremy Corbyn's campaign in the Labour Party leadership election. He said at a rally in Camden Town Hall: "I don't think electability really is the most important thing. What's important is that someone changes the conversation and moves us off this small-minded agenda."[140] He later wrote in The Guardian: "He's [Corbyn] been doing this with courage and integrity and with very little publicity. This already distinguishes him from at least half the people in Westminster, whose strongest motivation seems to have been to get elected, whatever it takes."[141]

In 2006, Eno was one of more than 100 artists and writers who signed an open letter calling for an international boycott of Israeli political and cultural institutions.[142] and in January 2009 he spoke out against Israel's military action on the Gaza Strip by writing an opinion for CounterPunch and participating in a large-scale protest in London.[143][144] In 2014, Eno again protested publicly against what he called a "one-sided exercise in ethnic cleansing" and a "war [with] no moral justification," in reference to the 2014 military operation of Israel into Gaza.[145] He was also a co-signatory, along with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Noam Chomsky, Alice Walker and others, to a letter published in The Guardian that labelled the conflict as an "inhumane and illegal act of military aggression" and called for "a comprehensive and legally binding military embargo on Israel, similar to that imposed on South Africa during apartheid."[146]

In 2013, Eno became a patron of Videre Est Credere (Latin for "to see is to believe"), a UK human rights charity.[147] Videre describes itself as "give[ing] local activists the equipment, training and support needed to safely capture compelling video evidence of human rights violations. This captured footage is verified, analysed and then distributed to those who can create change."[148] He participates alongside movie producers Uri Fruchtmann and Terry Gilliam – along with executive director of Greenpeace UK John Sauven.

On 3 December 2015, Eno appeared in a filmed public forum in London, titled "Basic income: How do we get there?", about the benefits and need for a basic income. It was hosted by Basic Income UK and also included economist Frances Coppola and anthropologist David Graeber.[149]

In autumn 2016, he became elected member of the 12 person Coordinating Collective (CC) of the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25), together with Noam Chomsky among other world-famous activists.

Eno was appointed President of Stop the War Coalition in 2017. He has had a long involvement with the organisation since it was set up in 2001.[150] He is also a trustee of the environmental law firm Client Earth, Somerset House, and the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, set up by Mariana Mazzucato.[151]

Eno opposes United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union. Following the June 2016 referendum result when the British public voted to leave, Eno was among a group of British musicians who signed a letter to the Prime Minister Theresa May calling for a second referendum.[152]

In November 2019, along with other public figures, Eno signed a letter supporting Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn describing him as "a beacon of hope in the struggle against emergent far-right nationalism, xenophobia and racism in much of the democratic world" and endorsed him for in the 2019 UK general election.[153] In December 2019, along with 42 other leading cultural figures, he signed a letter endorsing the Labour Party under Corbyn's leadership in the 2019 general election. The letter stated that "Labour's election manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership offers a transformative plan that prioritises the needs of people and the planet over private profit and the vested interests of a few."[154][155]

Discography

Solo studio albums

- Here Come the Warm Jets (1974), Island

- Taking Tiger Mountain (1974), Island

- Another Green World (1975), Island

- Discreet Music (1975), Obscure

- Before and After Science (1977), Polydor

- Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978), Polydor

- Music for Films (1978), Polydor

- Ambient 4: On Land (1982), EG

- Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks (1983), E.G.

- More Music for Films (1983), E.G.

- Thursday Afternoon (1985), E.G.

- Nerve Net (1992), Opal, All Saints

- The Shutov Assembly (1992), Opal, All Saints

- Neroli (1993), All Saints

- Headcandy (1994), BMG

- The Drop (1997), All Saints

- Another Day on Earth (2005), Hannibal

- Lux (2012), Warp

- The Ship (2016), Warp

- Reflection (2017), Warp

Ambient installation albums

- Extracts from Music for White Cube, London 1997 (1997), Opal

- Lightness: Music for the Marble Palace (1997), Opal

- I Dormienti (1999), Opal

- Kite Stories (1999), Opal

- Music for Civic Recovery Centre (2000), Opal

- Compact Forest Proposal (2001), Opal

- January 07003: Bell Studies for the Clock of the Long Now (2003), Opal

- Making Space (2010), Opal

See also

- List of ambient music artists

Footnotes

- The eventual length of The Microsoft Sound as supplied and used was roughly 6 seconds, not 3 1⁄4.

References

- Jason Ankeny. "Brian Eno | Biography & History". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- "Brian Eno Biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Steadman, Ian (28 September 2012). "Brian Eno on music that thinks for itself (Wired UK)". Wired UK. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "ABC news". Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Projects - The Long Now". Longnow.org. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Roxy Music". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "findmypast.co.uk". Search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "findmypast.co.uk". Search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "On Some FAraway Beach : The Life and Times of Brian Eno". Kindleweb.s3.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "findmypast.co.uk". Search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Pete Townshend (8 October 2012). Who I Am. HarperCollins. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-06-212726-6.

- Edward A. Shanken. "Cybernetics and Art : Cultural Convergence in the 1960s" (PDF). Responsivelandscapes.com. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- David Sheppard (1 May 2009). On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno. Chicago Review Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781556529429.

- "HOW WE MET: BRIAN ENO AND TOM PHILLIPS". The Independent. 13 September 1998. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Malcolm Le Grice Installation". Wkv-stuttgart.de. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Eno Left Roxy Music to do His Laundry". Contactmusic.com. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Prendergast, Mark (2001). The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Trance: The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-58234-134-7.

- Tannenbaum, Rob (27 August 2002). "Steadfast in Style". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

After two LPs, Eno left for a solo career, releasing briny albums of art-pop and inventing ambient music.

- Thompson, Dave. "All Music review". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Marsh, Peter (5 July 2004). "BBC – Experimental Review – Fripp Eno, The Equatorial Stars". BBC. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- {Prendergast, The Ambient Century: p.93}

- {(PVC7908(AMB001)}

- "How Brian Eno created a quiet revolution in music". The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- "Ambient 4: On Land 1986 release notes". Music.hyperreal.org. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Walters, John L. (22 July 2009). "Pop review: Brian Eno's Apollo". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Brian Eno explains Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks". The Guardian. 8 July 2009. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Trainspotting (1996)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Brian Eno: Nerve Net/The Shutov Assembly/Neroli/The Drop Album Review - Pitchfork". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Brian Eno interviewed by Michael Engelbrecht". Music.hyperreal.org. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music pp118-119 Ed. Nick Collins (ISBN 9780521688659)

- Foundation, The Long Now (30 November 2017). "Brian Eno Expands the Vocabulary of Human Feeling". Medium.com. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "miss+sarajevo | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Neverwhere (TV Mini-Series 1996– )". IMDb.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Dahlen, Chris (17 July 2006). "Interview: David Byrne". Pitchfork.

- Author, Unknown. "77-million-paintings-brian-eno". 77 Million Paintings. The Long Now Foundation. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Aizlewood, John. "In The Studio" Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Q Magazine. October 2007.

- "GameSpy: Spore - Page 2". Pc.gamespy.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Pitchfork: Source: Brian Eno Reveals Warp Album Details". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- "Brian Eno: Improvising Within The Rules". National Public Radio. 31 October 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- Troussé, Stephen (December 2010). "The Doctor Will See You Now". Uncut. Vol. 163.

- "Desire by Anna Calvi Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- "Drums Between The Bells & Panic of Looking". Brian Eno. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Carrie Battanon (26 September 2012). "Brian Eno Plans Solo Record for November". pitchfork.

- "Rachid Taha – Rock El Casbah feat. Mick Jones & Brian Eno – live at Stop the War concert". YouTube. 27 November 2005. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- "Damon Albarn Talks Solo Album 'Everyday Robots'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Brian Eno and Karl Hyde – Someday World: exclusive album stream". Guardian.com. 29 April 2014.

- Henry, Dusty (28 May 2014). ""Brian Eno and Karl Hyde announce new album, High Life, stream "DBF""". Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Gift feat. Brian Eno "Love Without Violins" – Official Videoclip", YouTube

- "Brian Eno – Reflection". Enoshop.co.uk. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Bucks Music Group » Reflection Nominated For Best New Age Album At The Grammys". Bucksmusicgroup.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Boomerang par Augustin Trapenard - France Inter". Franceinter.fr.

- "Stream Brian Eno & Roger Eno - Mixing Colours". consequenceofsound.net. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Pro Session – The Studio as Compositional Tool". Music.hyperreal.org. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "The History of David Bowie's Berlin Trilogy: 'Low,' 'Heroes' and 'Lodger'". Ultimateclassicrock.com. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Geoghegan, Kev; Saunders, Emma (11 January 2016). "Reaction to David Bowie's death". BBC Online. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Rohrlich, Justin (25 May 2010). "Who Created The Windows Start-Up Sound?". Minyanville's Wall Street. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Joel Selvin, Chronicle Pop Music Critic (2 June 1996). "Q and A With Brian Eno". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Adam Bunker, Technology Journalist (23 November 2011). "Brian Eno spills Windows start-up sound secrets". Electricpig. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Eno, Brian (2006). 77 Million Paintings "My Light Years". pp. 2.

- Eno, Brian (2006). "My Light Years". pp. 2.

- "NME: Proxy Music". Music.hyperreal.org. 9 November 1985. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- Eno, Brian (2006). "My Light Years". pp. 5.

- Eno, Brian (2006). "My Light Years". pp. 6–8.

- Dredge, Stuart (26 September 2012). "Brian Eno and Peter Chilvers talk Scape, iPad apps and generative music". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Generative Music – Brian Eno – In Motion Magazine". Inmotionmagazine.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Brian Eno Releases 'Music for Installations' on May 4th (2018)". Enoshop.co.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Brian Eno - Home". Brian Eno - Home. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Anthony Korner, Aurora Musicals, interview with Brian Eno Artforum 24 Summer 1986. Brian Eno Visual Music. P. 137 Christopher Scoates. ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- The Aesthetics of Time, Christopher Scoates, Brian Eno:Visual Music pp 344-345 ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- "Brian Eno is MORE DARK THAN SHARK". Moredarkthanshark.org. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Brian Eno Visual Music. Christopher Scoates pp.31-33 ISBN 978-1452108490

- Brian Eno Light Music p.9 Paul Stolper ISBN 978-0-9552154-9-0

- Steven Grant: Brian Eno Against Interpretation. Trouser Press, August 1982. Quoted in Brian Eno: Visual Music: Learning from Eno, Steven Dietz p.298. ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- "Brian Eno Q&A: The Infinite Art of". Wired. 2 July 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "BAMPFA - Art Exhibitions - Brian Eno / MATRIX 44". Archive.bampfa.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Brian Eno Visual Music. Christopher Scoates pp.116–117 ISBN 978-1452108490

- My Light Years Brian Eno accompanying essay to 77 Million Paintings. 2006 HNDVD 1521

- "Mistaken Memories Of Mediaeval Manhattan". Johncoulthart.com. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "BAMPFA - Art Exhibitions - Brian Eno / MATRIX 44". Archive.bampfa.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Eno: My Light Years. np. Brian Eno: Visual Music. Christopher Scoates. P121. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- Eno: My Light Years. np. Brian Eno: Visual Music. Christopher Scoates. P122. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- My Light Years Brian Eno np accompanying essay to 77 Million Paintings. 2006 HNDVD 1521

- Brian Eno : Visual Music: The Aesthetics of Time, Christopher Scoates, pp. 135–137, ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- Brian Eno Visual Music p.132 Christopher Scoates. ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- Brian Eno: Visual Music: The Aesthetics of Time: Christopher Scoates pp132/136 ISBN 978-1-4521-0849-0

- {Brian Eno Visual Music p.135 Christopher Scoates. ISBN 978-1452108490}

- "Brian Eno". SFMOMA. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- The Dynamics of Harmony: Pratt. ISBN 9780198790204

- Painting By Numbers, Nick Robertson, 77 Million Paintings HNDVD 1521

- Brian Eno Visual Music The Aesthetics of Time. Christopher Scoates. ISBN P. 124

- My Light Years by Brian Eno. 77 Million Paintings (accompanying booklet)HNDVD 1521

- "Composers as Gardeners". Edge.org. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Dreaper, Jane (19 April 2013). "Brian Eno branches out into hospital work". Bbc.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Eno and Chilvers Release Sweet Music App for iPhone |, Listening Post". Wired. 9 October 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Brian Eno". Facebook.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Brian Eno : Reflection on the App Store". App Store. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Brian Eno". Facebook.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "A Conversation With Brian Eno About Ambient Music – Pitchfork". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- Brian Eno - Light Music: Shedding Light. Michael Bracewell. Paul Stolper. ISBN 978-0-9552154-9-0

- "BRIAN ENO EXHIBITION WORKS - PAUL STOLPER - CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERY - LONDON". Paulstolper.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Nickalls, Susan. (23 July 1995). 'Music, the food of love'. The Independent. (United Kingdom).

- Dessau, Bruce (13 May 2010). "Laugh Lines: from Sergeant Bilko to Father Ted". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Vile, Gareth. (25 September 2011). 'Eno gets Brewed'. The Vile Blog. (Glasgow, Scotland).

- Higgins, Charlotte (27 November 2009). "Brian Eno to curate Brighton festival". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- As for a philosophical analysis of Lux, vid. Arena, op. cit., pp. 59–62

- 'Music innovator Brian Eno added to lecture series’ roll of honour'. Edinburgh University. (Scotland).

- Ferguson, Brian. (1 April 2016). 'Music legend Brian Eno to recall Edinburgh art school days'. The Scotsman. (Scotland).

- 'Brian Eno delivers the Andrew Carnegie Lecture'. Edinburgh University. (Scotland).

- Eno, Brian. (19 January 2017). 'Andrew Carnegie Lecture Series – Brian Eno'. Edinburgh University. YouTube. (Scotland).

- "81948 Eno (2000 OM69)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 June 2019.