Black rat

The black rat (Rattus rattus), also known as ship rat, roof rat, or house rat—is a common long-tailed rodent of the stereotypical rat genus Rattus, in the subfamily Murinae.[1]

| Black rat | |

|---|---|

| |

| A black rat, Rattus rattus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Muridae |

| Genus: | Rattus |

| Species: | R. rattus |

| Binomial name | |

| Rattus rattus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Mus rattus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The black rat is black to light brown in colour with a lighter underside. It is a generalist omnivore and a serious pest to farmers because it feeds on a wide range of agricultural crops. It is sometimes kept as a pet. In parts of India, it is considered sacred and respected in the Karni Mata Temple in Deshnoke.

Taxonomy

Mus rattus was the scientific name proposed by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 for the black rat.[2]

Three subspecies were once recognized, but today are considered invalid:

- Rattus rattus rattus – roof rat

- Rattus rattus alexandrinus – Alexandrine rat

- Rattus rattus frugivorus – fruit rat

Characteristics

A typical adult black rat is 12.75 to 18.25 cm (5.0 to 7.2 in) long, not including a 15 to 22 cm (5.9 to 8.7 in) tail, and weighs 75 to 230 g (2.6 to 8.1 oz), depending on the subspecies.[3][4][5][6] Despite its name, the black rat exhibits several colour forms. It is usually black to light brown in colour with a lighter underside. In England during the 1920s, several variations were bred and shown alongside domesticated brown rats. This included an unusual green-tinted variety.[7] The black rat also has a scraggly coat of black fur, and is slightly smaller than the brown rat.

Origin

Rattus rattus bone remains that date back to the Norman Period have been discovered in Britain. Evidence also suggests that R. rattus existed in prehistoric Europe as well as the Levant during post-glacial periods.[8] The specific origin of the black rat is uncertain due to the rat's disappearance and reintroduction. Evidence such as DNA and bone fragments also suggests that the rats did not originally come from Europe, but migrated from southeast Asia.[9]

Rats are resilient vectors for many diseases because of their ability to hold so many infectious bacteria in their blood. Rats played a primary role in spreading bacteria contained in fleas on their body, such as Yersinia pestis, which is responsible for the Plague of Justinian and the Black Death.[9] A study published in 2015 indicates that other Asiatic rodents served as plague reservoirs, from which infections spread as far west as Europe via trade routes, both overland and maritime. Although the black rat was certainly a plague vector in European ports, the spread of the plague beyond areas colonized by rats suggests that the plague was also circulated by humans after reaching Europe.[10]

The modern black rat was probably spread across Europe in the wake of the Roman conquest and arose from an ancestor that originated in southeast Asia, possibly Malaysia.[9] The Mediterranean black rats differ genetically from their southeast Asian ancestors by having 38 instead of 42 chromosomes.[9] Therefore, it seems that speciation could have occurred when the rats colonized southwest India, which was the primary country from which Romans obtained their spices. Because Rattus rattus is a passive traveler, they could have easily traveled to Europe during the trading between Rome and southwestern Asian countries. Evidence also suggests that, in 321–331 B.C., Egyptian birds were preying on Mediterranean rats, though this is not enough to prove that Egypt was the source of the rats.[9]

Diet

Black rats are considered omnivores and eat a wide range of foods, including seeds, fruit, stems, leaves, fungi, and a variety of invertebrates and vertebrates. They are generalists, and thus not very specific in their food preferences, which is indicated by their tendency to feed on any meal provided for cows, swine, chickens, cats, and dogs.[11] They are similar to the tree squirrel in their preference of fruits and nuts. They eat about 15 grams (0.53 oz) per day and drink about 15 millilitres (0.53 imp fl oz; 0.51 US fl oz) per day.[12] Their diet is high in water content.[11] They are a threat to many natural habitats because they feed on birds and insects. They are also a threat to many farmers, since they feed on a variety of agricultural-based crops, such as cereals, sugar cane, coconuts, cocoa, oranges, and coffee beans.[13]

Distribution and habitat

The black rat originated in India and Southeast Asia, and spread to the Near East and Egypt, and then throughout the Roman Empire, reaching Great Britain as early as the 1st century AD.[14] Europeans subsequently spread it throughout the world. The black rat is again largely confined to warmer areas, having been supplanted by the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) in cooler regions and urban areas. In addition to the brown rat being larger and more aggressive, the change from wooden structures and thatched roofs to bricked and tiled buildings favored the burrowing brown rats over the arboreal black rats. In addition, brown rats eat a wider variety of foods, and are more resistant to weather extremes.[15]

Black rat populations can increase exponentially under certain circumstances, perhaps having to do with the timing of the fruiting of the bamboo plant, and cause devastation to the plantings of subsistence farmers; this phenomenon is known as Mautam in parts of India.[16]

Black rats are thought to have arrived in Australia with the First Fleet, and subsequently spread to many coastal regions in the country.[17]

In New Zealand, black rats have an unusual distribution and importance, in that they are utterly pervasive through native forests, scrublands, and urban parklands. This is typical only of oceanic islands that lack native mammals, especially other rodents. Throughout most of the world, black rats are found only in disturbed habitats near people, mainly near the coast. Black rats are the most frequent predator of small forest birds, invertebrates, and perhaps lizards in New Zealand forests, and are key ecosystem changers. Controlling their abundance on large areas of the New Zealand mainland is a crucial current challenge for conservation managers.

Black rats adapt to a wide range of habitats. In urban areas they are found around warehouses, residential buildings, and other human settlements. They are also found in agricultural areas, such as in barns and crop fields. In urban areas, they prefer to live in dry upper levels of buildings, so they are commonly found in wall cavities and false ceilings. In the wild, black rats live in cliffs, rocks, the ground, and trees.[13] They are great climbers and prefer to live in palms and trees, such as pine trees. Their nests are typically spherical and made of shredded material, including sticks, leaves, other vegetation, and cloth. In the absence of palms or trees, they can burrow into the ground.[12] Black rats are also found around fences, ponds, riverbanks, streams, and reservoirs.[11]

Home range

Home range refers to the area in which an animal travels and spends most of its time. It is thought that male and female rats have similar sized home ranges during the winter, but male rats increase the size of their home range during the breeding season. Along with differing between rats of different sex, home range also differs depending on the type of forest in which the black rat inhabits. For example, home ranges in the southern beech forests of the South Island, New Zealand appear to be much larger than the non-beech forests of the North Island. Due to the limited number of rats that are studied in home range studies, the estimated sizes of rat home ranges in different rat demographic groups are inconclusive.

Nesting behavior

Through the usage of tracking devices such as radio transmitters, rats have been found to occupy dens located in trees, as well as on the ground. In Puketi Forest in the Northland Region of New Zealand, rats have been found to form dens together. Rats appear to den and forage in separate areas in their home range depending on the availability of food resources.[18] Research shows that, in New South Wales, the black rat prefers to inhabit lower leaf litter of forest habitat. There is also an apparent correlation between the canopy height and logs and the presence of black rats. This correlation may be a result of the distribution of the abundance of prey as well as available refuges for rats to avoid predators. As found in North Head, New South Wales, there is positive correlation between rat abundance, leaf litter cover, canopy height, and litter depth. All other habitat variables showed little to no correlation.[19] While this species' relative, the brown (Norway) rat prefers to nest near the ground of a building the black rat will prefer the upper floors and roof. Because of this habit they have been given the common name roof rat.

Foraging behavior

As generalists, black rats express great flexibility in their foraging behavior. They are predatory animals and adapt to different micro-habitats. They often meet and forage together in close proximity within and between sexes.[18] Rats tend to forage after sunset. If the food cannot be eaten quickly, they will search for a place to carry and hoard to eat at a later time.[11] Although black rats eat a broad range of foods, they are highly selective feeders; only a restricted number of the foods they eat are dominant foods.[20] When black rat populations are presented with a wide diversity of foods, they eat only a small sample of each of the available foods. This allows them to monitor the quality of foods that are present year round, such as leaves, as well as seasonal foods, such as herbs and insects. This method of operating on a set of foraging standards ultimately determines the final composition of their meals. Also, by sampling the available food in an area, the rats maintain a dynamic food supply, balance their nutrient intake, and avoid intoxication by secondary compounds.[20]

Ecology

Black rats (or their ectoparasites[21]) can carry a number of pathogens,[22] of which bubonic plague (via the Oriental rat flea), typhus, Weil's disease, toxoplasmosis and trichinosis are the best known. It has been hypothesized that the displacement of black rats by brown rats led to the decline of the Black Death.[23][24] This theory has, however, been deprecated, as the dates of these displacements do not match the increases and decreases in plague outbreaks.[25][26][27]

Predators and diseases

The black rat is prey to cats and owls in domestic settings. In less urban settings, rats are preyed on by weasels, foxes, and coyotes. These predators have little effect on the control of the black rat population because black rats are agile and fast climbers. In addition to agility, the black rat also uses its keen sense of hearing to detect danger and quickly evade mammalian and avian predators.[11]

Rats serve as outstanding vectors for transmittance of diseases because they can carry bacteria and viruses in their systems. A number of bacterial diseases are common to rats, and these include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Corynebacterium kutsheri, Bacillus piliformis, Pasteurella pneumotropica, and Streptobacillus moniliformis, to name a few. All of these bacteria are disease causing agents in humans. In some cases, these diseases are incurable.[28]

As an invasive species

Damage caused

After Rattus rattus was introduced into the northern islands of New Zealand, they fed on the seedlings adversely affecting the ecology of the islands. Even after eradication of R. rattus, the negative effects may take decades to reverse. When consuming these seabirds and seabird eggs, these rats reduce the pH of the soil. This harms plant species by reducing nutrient availability in soil, thus decreasing the probability of seed germination. For example, research conducted by Hoffman et al. indicates a large impact on 16 indigenous plant species directly preyed on by R. rattus. These plants displayed a negative correlation in germination and growth in the presence of black rats.[29] Rats prefer to forage in forest habitats. In the Ogasawara islands, they prey on the indigenous snails and seedlings. Snails that inhabit the leaf litter of these islands showed a significant decline in population on the introduction of Rattus rattus. The black rat shows a preference for snails with larger shells (greater than 10 mm), and this led to a great decline in the population of snails with larger shells. A lack of prey refuges makes it more difficult for the snail to avoid the rat.[30]

Complex pest

The black rat is a complex pest, defined as one that influences the environment in both harmful and beneficial ways. In many cases, after the black rat is introduced into a new area, the population size of some native species declines or goes extinct. This is because the black rat is a good generalist with a wide dietary niche and a preference for complex habitats; this causes strong competition for resources among small animals. This has led to the black rat completely displacing many native species in Madagascar, the Galapagos, and the Florida Keys. In a study by Stokes et al., habitats suitable for the native bush rat, Rattus fuscipes, of Australia are often invaded by the black rat and are eventually occupied by only the black rat. When the abundances of these two rat species were compared in different micro-habitats, both were found to be affected by micro-habitat disturbances, but the black rat was most abundant in areas of high disturbance; this indicates it has a better dispersal ability.[31]

Despite the black rat's tendency to displace native species, it can also aid in increasing species population numbers and maintaining species diversity. The bush rat, a common vector for spore dispersal of truffles, has been extirpated from many micro-habitats of Australia. In the absence of a vector, the diversity of truffle species would be expected to decline. In a study in New South Wales, Australia it was found that, although the bush rat consumes a diversity of truffle species, the black rat consumes as much of the diverse fungi as the natives and is an effective vector for spore dispersal. Since the black rat now occupies many of the micro-habitats that were previously inhabited by the bush rat, the black rat plays an important ecological role in the dispersal of fungal spores. By eradicating the black rat populations in Australia, the diversity of fungi would decline, potentially doing more harm than good.[31]

Control methods

Large-scale rat control programs have been taken to maintain a steady level of the invasive predators in order to conserve the native species in New Zealand such as kokako and mohua.[32] Pesticides, such as pindone and 1080 (sodium fluoroacetate), are commonly distributed via aerial spray by helicopter as a method of mass control on islands infested with invasive rat populations. Bait, such as brodifacoum, is also used along with coloured dyes (used to deter birds from eating the baits) in order to kill and identify rats for experimental and tracking purposes. Another method to track rats is the use of wired cage traps, which are used along with bait, such as rolled oats and peanut butter, to tag and track rats to determine population sizes through methods like mark-recapture and radio-tracking.[18] Tracking tunnels (coreflute tunnels containing an inked card) are also commonly used monitoring devices, as are chew-cards containing peanut butter [33] Poison control methods are effective in reducing rat populations to nonthreatening sizes, but rat populations often rebound to normal size within months. Besides their highly adaptive foraging behavior and fast reproduction, the exact mechanisms for their rebound is unclear and are still being studied.[34]

In 2010, the Sociedad Ornitológica Puertorriqueña (Puerto Rican Bird Society) and the Ponce Yacht and Fishing Club launched a campaign to eradicate the black rat from the Isla Ratones (Mice Island) and Isla Cardona (Cardona Island) islands off the municipality of Ponce, Puerto Rico.[35]

Decline in population

Rattus rattus populations were common in Great Britain, but began to decline after the introduction of the brown rat in the 18th century. R. rattus populations remained common in seaports and major cities until the late 19th century, but have been decreased due to rodent control and sanitation measures. The Shiant Islands in the Outer Hebrides in Scotland are often cited as the last remaining wild population of R. rattus left in Britain but evidence demonstrates that populations other than the Shiant Islands' survive on other islands and in localised areas of the British mainland.[36] Recent National Biodiversity Network data show populations around the U.K., particularly in ports and port towns.[37] This is supported by anecdotal records from London and Liverpool.

As of winter 2015 the Shiant Isles Recovery Project (a joint initiative between RSPB and Scottish Natural Heritage) is underway to eradicate Rattus rattus populations on the islands.[36]

See also

- Karni Mata Temple, Deshnoke, Rajasthan, India.

- Polynesian rat

- Urban plague

Further reading

- List of books and articles about rats

References

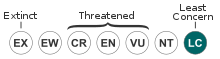

- Kryštufek, B.; Palomo, L.J.; Hutterer, R.; Mitsain, G. & Yigit, N. (2015). "Rattus rattus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T19360A115148682.

- Linnæus, C. (1758). "Mus rattus". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (Decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 61.

- "Black rat, House Rat, Roof Rat, Ship Rat (Rattus rattus)". WAZA.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Gillespie, H. (2004). "Rattus rattus — house rat". Animal Diversity Web.

- Schwartz, Charles Walsh and Schwartz, Elizabeth Reeder (2001). The Wild Mammals of Missouri, University of Missouri Press, ISBN 978-0-8262-1359-4, p. 250.

- Engels, Donald W. (1999). Classical Cats: The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-21251-9, p. 16.

- Alderton, D. (1996). Rodents of the World. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8160-3229-7

- Rackham, J (1979). "Rattus rattus: The introduction of the black rat into Britain". Antiquity. 53 (208): 112–20. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00042319. PMID 11620121.

- McCormick, M (2003). "Rats, Communications, and Plague: Toward an Ecological History" (PDF). Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 34 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1162/002219503322645439. ISSN 0022-1953.

- Schmidt; Büntgen; Easterday; Ginzler; Walløe; Bramanti; Stenseth (February 2015). "Climate-driven introduction of the Black Death and successive plague reintroductions into Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (10): 3020–3025. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.3020S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412887112. PMC 4364181. PMID 25713390.

- Marsh, Rex E. (1994). "Roof Rats". Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Bennet, Stuart M. "The Black Rat (Rattus Rattus)". The Pied Piper. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- "Rattus rattus – Roof rat". Wildlife Information Network. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Donald W. Engels. Classical Cats: The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 978-0-415-21251-9, p. 111.

- Teisha Rowland. "Ancient Origins of Pet Rats" Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Santa Barbara Independent, 4 December 2009.

- Nova: Rat Attack (PBS TV program), viewed 7 April 2010

- Evans, Ondine (1 April 2010). "Animal Species: Black Rat". Australian Museum website. Sydney, Australia: Australian Museum. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- Dowding, JE; Murphy, EC (1994). "Ecology of Ship Rats (Rattus rattus) in a Kauri (Agathis australis) Forest in Northland, New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 18 (1): 19–28. ISSN 0110-6465.

- Cox, MPG; Dickman, CR; Cox, WG (2000). "Use of habitat by the black rat (Rattus rattus) at North Head, New South Wales: an observational and experimental study". Austral Ecology. 25 (4): 375–85. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2000.01050.x.

- Clark, D. A. (1982). "Foraging behavior of vertebrate omnivore (Rattus rattus): Meal structure, sampling, and diet breadth". Ecology. 63 (3): 763–772. doi:10.2307/1936797. JSTOR 1936797.

- Hafidzi, M.N.; Zakry, F.A.A. & Saadiah, A. (2007). "Ectoparasites of Rattus sp. from Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia". Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science. 30 (1): 11–16.

- Meerburg BG, Singleton GR, Kijlstra A (2009). "Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health". Crit Rev Microbiol. 35 (3): 221–70. doi:10.1080/10408410902989837. PMID 19548807.

- Last, John M. "Black Death", Encyclopedia of Public Health, eNotes website. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- Barnes, Ethne (2007). Diseases and Human Evolution, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0-8263-3066-6, p. 247.

- Bollet, Alfred J. (2004). Plagues & Poxes: The Impact of Human History on Epidemic Disease, Demos Medical Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-1-888799-79-8, p. 23

- Carrick, Tracy Hamler; Carrick, Nancy and Finsen, Lawrence (1997). The Persuasive Pen: An Integrated Approach to Reasoning and Writing, Jones and Bartlett Learning, 1997, ISBN 978-0-7637-0234-2, p. 162.

- Hays, J. N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-658-9, p. 64.

- Boschert, Ken (27 March 1991). "Rat Bacterial Diseases". Net Vet and the Electronic Zoo. Archived from the original on 18 October 1996. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Grant-Hoffman, MN; Mulder, CP; Belingham, PJ (2009). "Invasive Rats Alter Woody Seedling Composition on Seabird-dominated Islands in New Zealand". Oecologia. 163 (2): 449–60. doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1523-6. ISSN 1442-9993. PMID 20033216.

- Chiba, S. (2010). "Invasive Rats Alter Assemblage Characteristics of Land Snails in the Ogasawara Islands". Biological Conservation. 143 (6): 1558–63. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.03.040.

- Vernes, K; Mcgrath, K (2009). "Are Introduced Black Rats (Rattus rattus) a Functional Replacement for Mycophagous Native Rodents in Fragmented Forests?". Fungal Ecology. 2 (3): 145–48. doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2009.03.001.

- Pryde, M; Dilks, P; Fraser, Ian (2005). "The home range of ship rats (Rattus rattus) in beech forest in the Eglinton Valley, Fiordland, New Zealand: a pilot study". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 32 (3): 139–42. doi:10.1080/03014223.2005.9518406.

- Jackson, Michael; Hartley, Stephen; Linklater, Wayne (1 June 2016). "Better food-based baits and lures for invasive rats Rattus spp. and the brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula: a bioassay on wild, free-ranging animals". Journal of Pest Science. 89 (2): 479–488. doi:10.1007/s10340-015-0693-8. ISSN 1612-4766.

- Innes, J; Warburton, B; Williams, D; et al. (1995). "Large-Scale Poisoning of Ship Rats (Rattus rattus) in Indigenous Forests of the North Island, New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 19 (1): 5–17.

- Wege, David (4 August 2010) Restauran hábitat del lagartijo del seco Anolis cooki en la Isla de Cardona y Cayo Ratones. birdlife.org.

- "The RSPB: Shiant Isles Seabird Recovery Project". www.rspb.org.uk. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "NBN Gateway – Taxon". data.nbn.org.uk. Retrieved 11 August 2016.