Andamanese

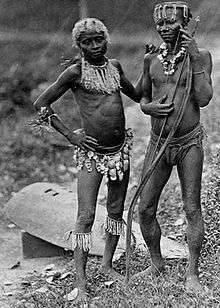

The Andamanese are the various indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands, part of India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territory in the southeastern part of the Bay of Bengal in Southeast Asia. The Andamanese peoples are among the various groups considered Negrito, owing to their dark skin and diminutive stature. All Andamanese traditionally lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and appear to have lived in substantial isolation for thousands of years.[1] It is suggested that the Andamanese settled in the Andaman Islands around the latest glacial maximum, around 26,000 years ago.[2][3]

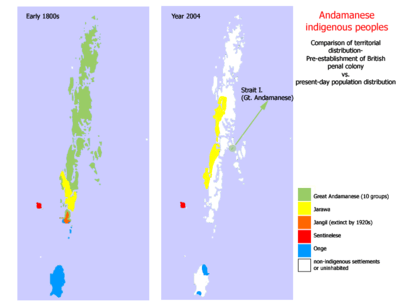

The Andamanese peoples included the Great Andamanese and Jarawas of the Great Andaman archipelago, the Jangil of Rutland Island, the Onge of Little Andaman, and the Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island.[4] At the end of the 18th century, when they first came into sustained contact with outsiders, an estimated 7,000 Andamanese remained. In the next century, they were largely wiped out by diseases, violence, and loss of territory. Today, only roughly 400–450 Andamanese remain, with the Jangil being extinct. Only the Jarawa and the Sentinelese maintain a steadfast independence, refusing most attempts at contact by outsiders.

The Andamanese are a designated Scheduled Tribe in India's constitution.[5]

History

Until the late 18th century, the Andamanese culture, language, and genetics were preserved from outside influences by their fierce reaction to visitors, which included killing any shipwrecked foreigners, and by the remoteness of the islands. The various tribes and their mutually unintelligible languages thus are believed to have evolved on their own over millennia.

Origins

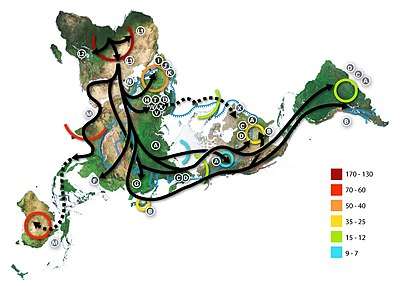

According to Chaubey and Endicott (2013), the Andaman Islands were settled less than 26,000 years ago, by people who were not direct descendants of the first migrants out of Africa.[6][note 1] According to Wang et al. (2011),

...the Andaman archipelago was likely settled by modern humans from northeast India via the land-bridge which connected the Andaman archipelago and Myanmar around the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a scenario in well agreement with the evidence from linguistic and palaeoclimate studies.[7]

It was previously assumed that the Andaman ancestors were part of the initial Great Coastal Migration that was the first expansion of humanity out of Africa, via the Arabian peninsula, along the coastal regions of the Indian mainland and toward Southeast Asia, China, and Oceania.[8][9] The Andamanese were considered to be a pristine example of a hypothesized Negrito population, which showed similar physical characteristics, and was supposed to have existed throughout southeast Asia. The existence of a specific Negrito-population is nowadays doubted. Their commonalities could be the result of evolutionary convergence and/or a shared history.[10][11]

Bulbeck (2013) shows the Andamanese maternal mtDNA is entirely mitochondrial Haplogroup M.[12] Their Y-DNA belong to the D haplogroup which has not been seen outside of the Andamans, a fact that underscores the insularity of these tribes. Analysis of mtDNA, which is inherited exclusively by maternal descent, confirms the above results. All Onge belong to mtDNA haplogroup M, which is unique to Onge people. This haplogroup, which is descended from Africa, represents the entire lineage of the Onge and Adamanese, and is the predominant mtDNA among the Semang in Malaysia. Moreover, haplogroup M is the single most common mtDNA haplogroup in Asia, where it represents 60% of all maternal lineages.[13][14]

A 2017 study by Mondal et al. finds that the Riang lineage of D1a3 (a Tibeto-Burmese population) and the Andamanese D1a3 have their nearest related lineages in East Asia. The Jarawa and Onge shared this D1a3 lineages with each other within the last ~7000 years, but had diverged from the Japanese D1a2 lineage ~53000 years ago". They further suggest that: “This strongly suggests that haplogroup D does not indicate a separate ancestry for Andamanese populations. Rather, haplogroup D was part of the standing variation carried by the OOA expansion, and later lost from most of the populations except in Andaman and partially in Japan and Tibet”.[15]

Population decline

The Andamanese's protective isolation changed with the first British colonial presence and subsequent settlements, which proved disastrous for them. Lacking immunity against common infectious diseases of the Eurasian mainland, the large Jarawa habitats on the southeastern regions of South Andaman Island likely were depopulated by disease within four years (1789–1793) of the initial British colonial settlement in 1789.[16] Epidemics of pneumonia, measles and influenza spread rapidly and exacted heavy tolls, as did alcoholism.[16] In the 19th century, the measles killed 50% of the Andamanese population.[17] By 1875, the Andamanese were already "perilously close to extinction," yet attempts to contact, subdue and co-opt them continued unrelentingly. In 1888, the British government set in place a policy of "organized gift giving" that continued in varying forms until well into the 20th century.[18]

There is evidence that some sections of the British Indian administration were working deliberately to annihilate the tribes.[19] After the mid-19th century, British established penal colonies on the islands and an increasing numbers of mainland Indian and Karen settlers arrived, encroaching on former territories of the Andamanese. This accelerated the decline of the tribes.

Many Andamanese succumbed to British expeditions to avenge the killing of shipwrecked sailors. In the 1867 Andaman Islands Expedition, dozens of Onge were killed by British naval personnel following the death of shipwrecked sailors, which resulted in four Victoria Crosses for the British soldiers.[20][21][22]

In 1923, the British ornithologist and anthropologist Frank Finn, who visited the islands in the 1890s, while working for the Indian Museum, described the Andamanese as "The World's Most Primitive People", writing:[23]

I used to envy the pigmies their simple costume, which in the case of the ladies was a wisp and a waistband, and in that of the men, nothing at all. Their interests are looked after by an English Civil Servant, who has to see that no one sells them drink, or interferes with them in any way; but even this officer-in-charge, as he is styled, dares not go among them where he is not known, and considerable tact is required in getting an introduction to the local chief.

In the 1940s, the Jarawa were bombed by imperial Japanese forces for their hostility. This attack of the Japanese was criticized as war crime by many observers.[24]

Recent history

In 1974, a film crew and anthropologist Triloknath Pandit attempted friendly contact by leaving a tethered pig, some pots and pans, some fruit, and toys on the beach at North Sentinel Island. One of the islanders shot the film director in the thigh with an arrow. The following year, European visitors were repulsed with arrows.[25][26][27]

On 2 August 1981, the Hong Kong freighter ship Primrose grounded on the North Sentinel Island reef. A few days later, crewmen on the immobile vessel observed that small black men were carrying spears and arrows and building boats on the beach. The captain of the Primrose radioed for an urgent airdrop of firearms so the crew could defend themselves, but did not receive them. Heavy seas kept the islanders away from the ship. After a week, the crew were rescued by an Indian navy helicopter.[28]

On 4 January 1991, Triloknath Pandit made the first known friendly contact with the Sentinelese.[27]

Until 1996, the Jarawa met most visitors with flying arrows. From time to time, they attacked and killed poachers on the lands reserved to them by the Indian government. They also killed some workers building the Andaman Trunk Road (ATR), which traverses Jarawa lands. One of the earliest peaceful contacts with the Jarawa occurred in 1996. Settlers found a teenaged Jarawa boy named Enmei near Kadamtala town. The boy was immobilized with a broken foot. They took Enmei to a hospital, where he received good care. Over several weeks, Enmei learned a few words of Hindi before returning to his jungle home. The following year, Jarawa individuals and small groups began appearing along roadsides and occasionally venturing into settlements to steal food. The ATR may have interfered with traditional Jarawa food sources.[29][30][31]

On 17 November 2018, a United States missionary, John Allen Chau, was killed when he tried to introduce Christianity to the Sentinelese tribe. The Sentinelese have been protected from contact with the outside world. Trips to the Island are prohibited by Indian law.[32] Chau was brought near the island by local fishermen, who were later arrested during the investigation into his death.[33] Indian authorities attempted to retrieve Chau's remains without success.[34]

Tribes

The five major groups of Andamanese are:

- Great Andamanese, traditionally of the Great Andaman archipelago but now living on Strait Island. Their population was 52 as of 2010.[35]

- Jarawa traditionally of the southern part of South Andaman Island in the Great Andaman archipelago but now living in the ex-Great Andamanese homeland in the West Coast and central parts of South and Middle Andaman Islands. Their population was 380 as of 2011.[36]

- Jangil or Rutland Jarawa of Rutland Island, extinct by 1921[24]

- Onge of Little Andaman, at 101 individuals as of 2011.[36]

- Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island, estimated to be 100 to 200 individuals.

By the end of the eighteenth century, there were an estimated 5,000 Great Andamanese living on Great Andaman. Altogether they comprised ten distinct tribes with different languages. The population quickly dwindled to 600 in 1901 and to 19 by 1961.[37] It has increased slowly after that, following their move to a reservation on Strait Island. As of 2010, the population was 52, representing a mix of the former tribes.[35]

The Jarawa originally inhabited southeastern Jarawa Island and have migrated to the west coast of Great Andaman in the wake of the Great Andamanese. The Onge once lived throughout Little Andaman and now are confined to two reservations on the island. The Jangil, who originally inhabited Rutland Island, were extinct by 1931; the last individual was sighted in 1907.[24] Only the Sentinelese are still living in their original homeland on North Sentinel Island, largely undisturbed, and have fiercely resisted all attempts at contact.

Languages

The Andamanese languages are considered to be the fifth language family of India, following the Indo-European, Dravidian, Austroasiatic, and Sino-Tibetan.[38]

While some connections have been tentatively proposed with other language families,[39] the consensus view is currently that Andamanese languages form a separate language family – or rather, two unrelated linguistic families: Greater Andamanese[40] and Ongan.

Culture

Until contact, the Andamanese were strict hunter-gatherers. They did not practice cultivation, and lived off hunting indigenous pigs, fishing, and gathering. Their only weapons were the bow, adzes, and wooden harpoons. With the aboriginal people of Tasmania, the Andamanese were one of only two peoples who in the nineteenth century knew of no method for making fire.[41]:229 They instead carefully preserved embers[41]:229 in hollowed-out trees from fires caused by lightning strikes.

The men wore girdles made of hibiscus fiber which carried useful tools and weapons for when they went hunting. The women on the other hand wore a tribal dress containing leaves that were held by a belt. A majority of them had painted bodies as well. They usually slept on leaves or mats and had either permanent or temporary habitation among the tribes. All habitations were man made.[42]

Some of the tribe members were credited to having supernatural powers. They were called oko-pai-ad, which meant dreamer. They were thought to have an influence on the members of the tribe and would bring misfortune to those who did not believe in their abilities. Traditional knowledge practitioners were the ones who helped with healthcare. The medicine that was used to cure illnesses were herbal most of the time. Various types of medicinal plants were used by the islanders. 77 total traditional knowledge practitioners were identified and 132 medicinal plants were used. The members of the tribes found various ways to use leaves in their everyday lives including clothing, medicine, and to sleep on.[43]

Anthropologist A.R. Radcliffe Brown argued that the Andamanese had no government and made decisions by group consensus.[44]

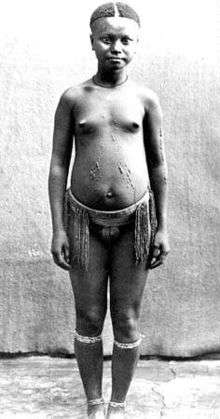

Physical appearance

Phenotype

Negritos, specifically Andamanese, are grouped together by phenotype and anthropological features. Three physical features that distinguish the Andaman islanders include: skin colour, hair, and stature. Those of the Andaman islands have dark skin, are short in stature, and have "frizzy" hair.[12]

Dental morphology

Dental characteristics also group the Andamanese between Negrito and East-Asian samples.[46]

When comparing dental morphology the focus is on overall size and tooth shape. To measure the size and shape, Penrose's size and shape statistic is used. To calculate tooth size, the sum of the tooth area is taken. Factor analysis is applied to tooth size to achieve tooth shape. Results have shown that the dental morphology of Andaman Islanders resembles that of South Asians, whereas Philippine Negrito groups more closely resemble southeast Asians in their dental morphology. Therefore, the dental morphology of the Andamanese indicates a retention of dental morphology from early South Asians in the early-mid Holocene. Overall the dental morphology of the Andamanese is found to be distant from that of modern East Asians. However it is noted that the tooth size of the Andamanese is similar to that of the Han Chinese and Japanese.[12]

Genetics

Genetic analysis, both of nuclear DNA[8][47] and mitochondrial DNA[48] provide information about the origins of the Andamanese. The Andamanese are most genetically similar to the Malaysian Negrito tribe.[49]

Nuclear DNA

The Andamanese show a very small genetic variation, which is indicative of populations that have experienced a population bottleneck and then developed in isolation for a long period.

An allele has been discovered among the Jarawas that is found nowhere else in the world. Blood samples of 116 Jarawas were collected and tested for Duffy blood group and malarial parasite infectivity. Results showed a total absence of both Fya and Fyb antigens in two areas (Kadamtala and R.K Nallah) and low prevalence of both Fya antigen in another two areas (Jirkatang and Tirur). There was an absence of malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax infection though Plasmodium falciparum infection was present in 27·59% of cases. A very high frequency of Fy (a–b–) in the Jarawa tribe from all the four jungle areas of Andaman Islands along with total absence of P. vivax infections suggests the selective advantage offered to Fy (a–b–) individuals against P. vivax infection.[50]

Overall, the Andamanese showed closest relations with other Oceanic populations. The Nicobarese in contrast were observed to share close genetic relations with adjacent Indo-Mongoloid populations of Northeast India and Myanmar.[47] Bulbeck (2013) likewise noted that the Andamanese's nuclear DNA clusters with that of other Andamanese Islanders, as they carry a unique branch of Haplogroup D (D1a3) and maternal M (mtDNA).[12]

Genomic

The use of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) shows that the genome of Andamanese people is closest to those of other Oceanic Negrito groups and distinct from South Asians and East Asians.[12] Analysis of mtDNA, which is inherited exclusively by maternal descent, confirms the above results. All Onge belong to M32 mtDNA, a subgroup of M which is unique to Onge people.[48]

According to Reich et al. (2009). South Asian populations of the Indian subcontinent are composed, to significantly varying degrees, of mixtures of ancestry from: a group (known as "ASI" or "Ancestral South Indian") closest to but distinct from Andaman islanders, and populations from Western Eurasia (comprising a component termed "ANI" or "Ancestral North Indian").[51] Reich et al. speculate that the Andamanese split from mainland Asia 1,700 generations ago.[52] Andamanese are the only South Asian population in the study that lacked any Ancestral North Indian admixture.[52] According to Basu et al. (2016), the populations of the Andaman Islands archipelago form a distinct ancestry, which is "coancestral to Oceanic populations and not close to South Asians (India)." They conclude that the Andamanese, though they may be the closest existing group to the ancient "ASI" ancestral component in modern South Asians, have a distinct ancestry and are not closely related to other South Asians but are closer to Southeast Asian Negritos.[53]

Moorjani et al. 2013 state that the "ASI" component in South Asians, though not closely related to any living group, is "related (distantly) to indigenous Andaman Islanders." Moorjani et al. also suggest possible gene flow into the Andamanese from a population related to the ASI. The study concluded that “almost all groups speaking Indo-European or Dravidian languages lie along a gradient of varying relatedness to West Eurasians in PCA (referred to as “Indian cline”)”.[46]

A genetic analysis from Chaubey et al. 2015 found evidence of East Asian (Han Chinese-related) ancestry in Andamanese people. They estimated 32% East Asian ancestry in the Onge and 31% in the Great Andamanese, but suggest that this finding also may reflect the genetic affinity of the Andamanese to Melanesian and Southeast Asian Negrito populations (stating that "The Han ancestry measured in Andaman Negrito is probably partially capturing both Melanesian and Malaysian Negrito ancestry"),[3] as a previous study by Chaubey et al. suggested "a deep common ancestry" between Andamanese, Melanesians and other Negrito groups (as well as South Asians), and an affinity between Southeast Asian Negritos and Melanesians with East Asians.[54]

McColl et al. (2018) Analysed 26 ancient samples from Southeast Asia and Japan spanning from the late Neolithic to the Iron Age, along with an ancient Ikawazu Jōmon sample from southeast Honshu.The Jomon female skeleton which was analyzed shows typical Jōmon morphology.[55] However this Jōmon individual partially shares some ancestry with prehistoric Hoabinhians, which in turn also share some ancestry with the Onge, Jehai (Peninsular Malaysia) in mainland Southeast Asia along with Indian groups and Papua New Guineans, which represents possible gene flow from that group into the Jōmon population.[56] The Jōmon individual is best modeled as a mix of Hòabìnhian (La368) and East Asian ancestry while present-day East Asians can be modeled as a mixture of an Önge-like population and a population related to the Tiányuán individual.[57][58] However, there is still lack of ancient genome data to understand the peopling history of East Eurasians. It is required to analyze more ancient genome data, if there found appropriate skeletons, in order to fill the gap and to prove the speculation.[59]

A study by Narasimhan et al. (2018) concludes that ANI and ASI were formed in the 2nd millennium BCE, and were preceded by a mixture of AASI (Ancient Ancestral South Indian, i.e. hunter-gatherers sharing a common root with the Andamanese); and Iranian agriculturalists who arrived in India ca. 4700–3000 BCE, and "must have reached the Indus Valley by the 4th millennium BCE".[60] Narasimhan et al. observe that samples from the Indus periphery population are always mixes of the same two proximal sources of AASI and Iranian agriculturalist-related ancestry; with "one of the Indus Periphery individuals having ~42% AASI ancestry and the other two individuals having ~14-18% AASI ancestry" (with the remainder of their ancestry being from the Iranian agriculturalist-related population). According Narasimhan the genetic makeup of the ASI population consisted of about 73% AASI and about 27% from Iran-related peoples.[60]

Another genetic study by Yelmen et al. (2019) shows that the native South Asian genetic component is distinct from the Andamanese and thus that the Andamanese (Onge) are an imperfect and imprecise proxy for "ASI" ancestry in South Asians (there is difficulty detecting ASI ancestry in the North Indian Gujarati when the Andamanese Onge are used). Yemen et al. suggest that the South Indian tribal Paniya people would serve as a better proxy than the Andamanese (Onge) for the "native South Asian" component in modern South Asians.[61]

Two more recent genetic studies (Shinde et al. 2019 and Narasimhan et al. 2019) on remains from the Indus Valley civilisation (of parts of Bronze Age northwest India and east Pakistan) found them to have a mixed ancestry: The samples analyzed by Shinde et al. had about 50-98% of their genome from Iranian hunter-gatherer peoples, which were also ancestral to Iranian farmers, and from 2-50% from South-east Asian hunter-gatherers sharing a common ancestry with the Andamanese, with the Iranian ancestry being on average predominant. The samples analyzed by Narasimhan et al. had 45–82% Iranian-related ancestry and 11–50% AASI (or Andamanese-related hunter-gatherer ancestry). The analysed samples of both studies have little to none of the "Steppe ancestry" component associated with later Indo-European migrations into India. The authors found that the respective amounts of those ancestries varied significantly between individuals, and concluded that more samples are needed to get the full picture of Indian population history. Further Narasimhan et al. 2019 notes that the high correlation between Dravidian and ASI ancestry may suggest that the Dravidians originated from the AASI component and are native to peninsular South Asia (south and east India).[62][63]

Y DNA

_migration.png)

The male Y-chromosome in humans is inherited exclusively through paternal descent. All sampled males of Onges (23/23) and Jarawas (4/4) belong to Paragroup D-M174*(D1a3).[64][65][66][67] However, male Great Andamanese do not appear to carry these clades. A low resolution study suggests that they belong to haplogroups K, L, O and P1 (P-M45).[68]

A 2017 study by Mondal et al. finds that Andamanese D lineages diverged from Japanese D lineages lineage ~53000 years ago" and that Andamanese D lineages and those of the Riang (a Tibeto-Burmese population) have their nearest related lineages in East Asia, also finding that the D lineages of the Jarawa and Onge (both Andamanese groups) share a common ancestry more recently, within the last ~7000 years. They further suggest that: “This strongly suggests that haplogroup D does not indicate a separate ancestry for Andamanese populations. Rather, haplogroup D was part of the standing variation carried by the OOA expansion, and later lost from most of the populations except in Andaman and partially in Japan and Tibet”.[15]

Mitochondrial DNA

Analysis of mtDNA, which is inherited exclusively by maternal descent, confirms the above results. The Onge and all the Adamanan Islanders belong strictly to the mitochondrial Haplogroup M. All Andamanese belong to M31 and M32 mtDNA, a subgroup of M which is unique to Andamanese people.[12][48] The analysis of 20 coding regions in 20 samples of ancient Andamanese people and 12 samples of modern Indian populations changed the topology of the two lineages in South Asians. The data received suggests an M31a lineage in South Asians and in East Asians.[69] Other mainland specific subgroups of M are distributed in Asia, where they represent 60% of all maternal lineages.[68][70][71] According to Endicott et al. (2002), this haplogroup originated with the earliest settlers of India during the coastal migration that may have brought the ancestors of the Andamanese to the Indian mainland, the Andaman Islands, and farther afield to Southeast Asia.[72]

Archaic Admixture

Unlike some Negrito populations of Southeast Asia, Andaman Islanders have not been found to have Denisovan ancestry.[73] However, they are estimated, like all other non-African populations, to possess approximately 1-2% Neanderthal ancestry.[74] A study suggests that all Asian and Australo-Papuan populations, including Andaman Islanders, also share between 2.6 and 3.4% of the genetic profile of a previously unknown hominin that was genetically roughly equidistant to Denisovans and Neandertals.[75][74] However, a 2018 study by Skoglund et al. lead by the Harvard Reich lab team did not replicate that result and did not find evidence for admixture from an unknown hominin in the Andamanese or other Asians.[76] Wall et al. 2019 also did not find evidence of unknown archaic hominin admixture in Andamanese.[77]

See also

- Adivasis

- Andamanese languages

- Uncontacted peoples

- Early human migrations

Notes

- Chaubey and Endicott (2013):[6]

* "these estimates suggest that the Andamans were settled less than ~26 ka and that differentiation between the ancestors of the Onge and Great Andamanese commenced in the Terminal Pleistocene." (p.167)

* "In conclusion, we find no support for the settlement of the Andaman Islands by a population descending from the initial out-of-Africa migration of humans, or their immediate descendants in South Asia. It is clear that, overall, the Onge are more closely related to Southeast Asians than they are to present-day South Asians." (p.167)

References

- Joseph, Tony (22 December 2018). "Getting to know the Andamanese". www.livemint.com.

- Mondal, Mayukh; Bergström, Anders; Xue, Yali; Calafell, Francesc; Laayouni, Hafid; Casals, Ferran; Majumder, Partha P.; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Bertranpetit, Jaume (1 May 2017). "Y-chromosomal sequences of diverse Indian populations and the ancestry of the Andamanese". Human Genetics. 136 (5): 499–510. doi:10.1007/s00439-017-1800-0. hdl:10230/34399. ISSN 1432-1203. PMID 28444560.

In contrast, the Riang (Tibeto-Burman-speaking) and Andamanese have their nearest neighbour lineages in East Asia. The Jarawa and Onge shared haplogroup D lineages with each other within the last ~7000 years, but had diverged from Japanese haplogroup D Y-chromosomes ~53000 years ago, most likely by a split from a shared ancestral population.

- Chaubey (2015). "East Asian ancestry in India".

- "Sentinel island: When British toyed with idea to unleash Gurkhas on Sentinelese". The Times of India.

- "List of notified Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). Census India. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a Regional Genetic Context: Reexamining the Evidence for an Early Peopling of the Archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–172. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. PMID 24297224.

- Wang, Hua-Wei; Mitra, Bikash; Chaudhuri, Tapas Kumar; Palanichamy, Malliya gounder; Kong, Qing-Peng; Zhang, Ya-Ping (20 March 2011). "Mitochondrial DNA evidence supports northeast Indian origin of the aboriginal Andamanese in the Late Paleolithic". Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 38 (3): 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2011.02.005. PMID 21477783.

- Spencer Wells (2002), The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-11532-0,

... the population of south-east Asia prior to 6000 years ago was composed largely of groups of hunter-gatherers very similar to modern Negritos ... So, both the Y-chromosome and the mtDNA paint a clear picture of a coastal leap from Africa to south-east Asia, and onward to Australia ... DNA has given us a glimpse of the voyage, which almost certainly followed a coastal route va India ...

- Anvita Abbi (2006), Endangered Languages of the Andaman Islands, Lincom Europa,

... to Myanmar by a land bridge during the ice ages, and it is possible that the ancestors of the Andamanese reached the islands without crossing the sea ... The latest figure in 2005 is 50 in all ...

- Jinam, Timothy A.; Phipps, Maude E.; Saitou, Naruya (1 June 2013). "Admixture Patterns and Genetic Differentiation in Negrito Groups from West Malaysia Estimated from Genome-wide SNP Data". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 173–188. doi:10.3378/027.085.0308. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 24297225.

- Stock, Jay T. (1 January 2013). "The Skeletal Phenotype of "Negritos" from the Andaman Islands and Philippines Relative to Global Variation among Hunter-Gatherers". Human Biology. 85 (1): 67–94. doi:10.3378/027.085.0304. ISSN 1534-6617. PMID 24297221.

- Bulbeck, David (November 2013). "Craniodental Affinities of Southeast Asia's "Negritos" and the Concordance with Their Genetic Affinities". Human Biology. 85 (1): 95–134. doi:10.3378/027.085.0305. PMID 24297222. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Ghezzi; et al. (2005). "Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease in Italians". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (6): 748–752. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201425. PMID 15827561.

- name="petraglia2007">Michael D. Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (2007), The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4,

... As haplogroup M, except for the African sub-clade M1, is not notably present in regions west of the Indian subcontinent, while it covers the majority of Indian mtDNA variation ...

- Mondal, Mayukh; Bergström, Anders; Xue, Yali; Calafell, Francesc; Laayouni, Hafid; Casals, Ferran; Majumder, Partha P.; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Bertranpetit, Jaume (1 May 2017). "Y-chromosomal sequences of diverse Indian populations and the ancestry of the Andamanese". Human Genetics. 136 (5): 499–510. doi:10.1007/s00439-017-1800-0. hdl:10230/34399. ISSN 1432-1203. PMID 28444560.

In contrast, the Riang (Tibeto-Burman-speaking) and Andamanese have their nearest neighbour lineages in East Asia. The Jarawa and Onge shared haplogroup D lineages with each other within the last ~7000 years, but had diverged from Japanese haplogroup D Y-chromosomes ~53000 years ago, most likely by a split from a shared ancestral population.

- Sita Venkateswar (2004), Development and Ethnocide: Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands, IWGIA, ISBN 978-87-91563-04-1,

As I have suggested previously, it is probable that some disease was introduced among the coastal groups by Lieutenant Colebrooke and Blair's first settlement in 1789, resulting in a marked reduction of their population. The four years that the British occupied their initial site on the south-east of South Andaman were sufficient to have decimated the coastal populations of the groups referred to as Jarawa by the Aka-bea-da.

- Measles hits rare Andaman tribe Archived 23 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 16 May 2006.

- Richard B. Lee; Richard Heywood Daly (1999), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57109-8,

By 1875, when these peoples were perilously close to extinction, the Andaman cultures came under scientific scrutiny ... In 1888, 'friendly relations' were established with Ongees through organized gift giving contacts ... As recently as 1985—92, government contacts have been initiated with Jarawas and Sentinelese through gift-giving, a contact procedure much like that carried out during British rule.

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Francesco Cavalli-Sforza (1995), The Great Human Diasporas: The History of Diversity and Evolution, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-201-44231-1,

Contact with whites, and the British in particular, has virtually destroyed them. Illness, alcohol, and the will of the colonials all played their part; the British governor of the time mentions in his diary that he received instructions to destroy them with alcohol and opium. He succeeded completely with one group. The others reacted violently.

- Madhusree Mukerjee (2003), The Land of Naked People, Houghton Mifflin Books, ISBN 978-0-618-19736-1,

In 1927 Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, a German anthropologist, found that around 100 Great Andamanese survived, 'in dirty, half-closed huts, which primarily contain cheap European household effects'.

- "No. 23333". The London Gazette. 17 December 1867. p. 6878.

- Laxman Prasad Mathur (2003), Kala Pani: History of Andaman & Nicobar Islands, with a Study of Indiaʼs Freedom Struggle, Eastern Book Corporation,

Snippet: "Immediately afterwards in another visit to Little Andaman to trace the sailors of a ship named 'Assam Valley' wrecked on its coast, Homfray's party was attacked by a large group of Onges."

- Finn, Frank (26 October 1923). "The World's Most Primitive People". The Radio Times.

- George van Driem (2001), Languages of the Himalayas: An Ethnolinguistic Handbook of the Greater Himalayan Region: Containing an Introduction to the Symbiotic Theory of Language, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-12062-4,

... The Aka-Kol tribe of Middle Andaman became extinct by 1921. The Oko-Juwoi of Middle Andaman and the Aka-Bea of South Andaman and Rutland Island were extinct by 1931. The Akar-Bale of Ritchie's Archipelago, the Aka-Kede of Middle Andaman and the A-Pucikwar of South Andaman Island soon followed. By 1951, the census counted a total of only 23 Greater Andamanese and 10 Sentinelese. That means that just ten men, twelve women and one child remained of the Aka-Kora, Aka-Cari and Aka-Jeru tribes of Greater Andaman and only ten natives of North Sentinel Island ...

- Goodheart, Adam (Autumn 2000). "The Last Island of the Savages". The American Scholar. 69 (4): 13–44. JSTOR 41213066.

- Pandit

- "Islanders running out of isolation: Tim McGirk in the Andaman Islands reports on the fate of the Sentinelese". The Independent. London. 10 January 1993.

- "Grounding". neatorama.com.

- Seksharia, Pankaj. "Jarawa excursions". frontline.in. Front Line. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Valley, Paul. "Under threat: an ancient tribe emerging from the forests". listserv.linguist.org. The Independent UK. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Grig, Sophie. "Remote Jarawa tribe kill poacher – exclusive interview shows Jarawa denouncing poaching on their land". survivalinternational.org. Survival International. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "US man killed on remote island prepared for years for mission and 'may not have acted alone'". The Independent. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Staff, Scroll. "American missionary killed by Sentinelese was on a 'planned adventure', says scheduled tribes panel". Scroll.in. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Griswold, Eliza (8 December 2018). "John Chau's Death on North Sentinel Island Roils the Missionary World". The New Yorker. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Language lost as last member of Andaman tribe dies" (5 February 2010). The Daily Telegraph, London. Accessed 3 January 2017.

- http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/PCA/SC_ST/PCA-A11_Appendix/ST-35-PCA-A11-APPENDIX.xlsx

- Jayanta Sarkar (1990), The Jarawa, Anthropological Survey of India, ISBN 978-81-7046-080-0,

The Great Andamanese population was large till 1858 when it started declining ... In 1901, their number was reduced to only 600 and in 1961 to a mere 19.

- Zide, Norman; Pandya, Vishvajit (1989). "A Bibliographical Introduction to Andamanese Linguistics". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (4): 639–651. doi:10.2307/604090. JSTOR 604090.

- Blevins, Juliette (2007). "A Long Lost Sister of Proto-Austronesian?: Proto-Ongan, Mother of Jarawa and Onge of the Andaman Islands". Oceanic Linguistics. 46: 154–198. doi:10.1353/ol.2007.0015.

- "A Grammar of the Great Andamanese Language : An Ethnolinguistic Study". eds.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- François Bordes (2003). Leçons sur le Paléolithique. CNRS Éditions. p. 229. ISBN 978-2-271-05836-2.

Récemment encore les Indigènes des îles Andaman ne savaient pas allumer le feu, et le conservaient dans des caches, qu'ils rallumaient à l'occasion avec des brandons empruntés aux peuples voisins.

- Man, Edward Horace; Ellis, Alexander John (1 January 1932). The Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands. Mittal Publications.

- "EBSCO Publishing Service Selection Page". eds.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Brown, A.R. Radcliffe (1933). The Andaman Islanders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 44.

- Brown, A. R. (1909). "The Religion of the Andaman Islanders". Folklore. 20 (3): 257–271. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1909.9719883. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1254079.

- Moorjani P, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Lipson M, Loh PR, Govindaraj P, et al. (September 2013). "Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India". American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (3): 422–38. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. PMC 3769933. PMID 23932107.

- V. K. Kashyap; Sitalaximi T.; B. N. Sarkar; R. Trivedi1 (2003), "Molecular Relatedness of The Aboriginal Groups of Andaman and Nicobar Islands with Similar Ethnic Populations" (PDF), International Journal of Human Genetics, 3 (1): 5–11, doi:10.1080/09723757.2003.11885820, retrieved 8 June 2009,

... the Negrito populations of Andaman Islands have remained in isolation ... the Andamanese are more closely related to other Asians than to modern day Africans ... the Nicobarese exhibiting a close affinity with geographically proximate Indo-Mongoloid populations of Northeast India ...

- M. Phillip Endicott; Thomas P. Gilbert; Chris Stringer; Carles Lalueza-Fox; Eske Willerslev; Anders J. Hansen; Alan Cooper (2003), "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders" (PDF), American Journal of Human Genetics, 72 (1): 178–184, doi:10.1086/345487, PMC 378623, PMID 12478481, retrieved 21 April 2009,

... The HVR-1 data separate them into two lineages, identified on the Indian mainland (Bamshad et al. 2001) as M4 and M2 ... The Andamanese M2 contains two haplotypes ... developed in situ, after an early colonization ... Alternatively, it is possible that the haplotypes have become extinct in India or are present at a low frequency and have not yet been sampled, but, in each case, an early settlement of the Andaman Islands by an M2-bearing population is implied ... The Andaman M4 haplotype ... is still present among populations in India, suggesting it was subject to the late Pleistocene population expansions ...

- Aghakhanian, F.; Yunus, Y.; Naidu, R.; Jinam, T.; Manica, A.; Hoh, B. P.; Phipps, M. E. (14 April 2015). "Unravelling the Genetic History of Negritos and Indigenous Populations of Southeast Asia" (PDF). Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (5): 1206–1215. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv065. PMC 4453060. PMID 25877615. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- "The Duffy blood groups of Jarawas - The primitive and vanishing tribe of Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India | Request PDF". ResearchGate. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Reich 2009a, p. 40.

- Reich, David; Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Nick Patterson; Alkes L. Price; Lalji Singh (24 September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian Population History". Nature. 461 (7263): 489–494. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210. PMID 19779445.

- Basu 2016, p. 1594.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (1 February 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a regional genetic context: reexamining the evidence for an early peopling of the archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–172. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. ISSN 1534-6617. PMID 24297224.

- https://www.kanazawa-u.ac.jp/latest-research/59409

- Willerslev, Eske; Lambert, David M.; Higham, Charles; Oota, Hiroki; Phipps, Maude E.; Sikora, Martin; Orlando, Ludovic; Lahr, Marta Mirazón; Foley, Robert A. (6 July 2018). "The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia". Science. 361 (6397): 88–92. Bibcode:2018Sci...361...88M. doi:10.1126/science.aat3628. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29976827.

“Finally, the Jōmon individual is best-modeled as a mix between a population related to group 1/Önge and a population related to East Asians (Amis)” and “The oldest layer consists of mainland Hòabìnhians (group 1), who share ancestry with present-day Andamanese Önge, Malaysian Jehai, and the ancient Japanese Ikawazu Jōmon. Consistent with the two-layer hypothesis in MSEA, we observe a change in ancestry by ~4 ka ago, supporting a demographic expansion from EA into SEA during the Neolithic transition to farming.” and “Group 1 individuals differ from the other Southeast Asian ancient samples in containing components shared with the supposed descendants of the Hòabìnhians: the Önge and the Jehai (Peninsular Malaysia), along with groups from India and Papua New Guinea.”

- Fig. 3 Admixture graphs fitting ancient Southeast Asian genomes

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/361/6397/88

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/03/15/579177.full.pdf

- Narasimhan et al. 2018, p. 15.

- Yelmen, Burak; Mondal, Mayukh; Marnetto, Davide; Pathak, Ajai K.; Montinaro, Francesco; Gallego Romero, Irene; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait; Pagani, Luca (1 August 2019). "Ancestry-Specific Analyses Reveal Differential Demographic Histories and Opposite Selective Pressures in Modern South Asian Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (8): 1628–1642. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz037. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 6657728. PMID 30952160.

- Shinde V, Narasimhan VM, Rohland N, Mallick S, Mah M, Lipson M, Nakatsuka N, Adamski N, Broomandkhoshbacht N, Ferry M, Lawson AM, Michel M, Oppenheimer J, Stewardson K, Jadhav N, Kim YJ, Chatterjee M, Munshi A, Panyam A, Waghmare P, Yadav Y, Patel H, Kaushik A, Thangaraj K, Meyer M, Patterson N, Rai N, Reich D (September 2019). "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers". Cell. 179 (3): 729–735.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.048. PMC 6800651. PMID 31495572.

- Narasomhan VM, et al. (September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Kumarasamy; et al. (2003). "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population". Current Biology. 13 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01336-2.

- "Y-DNA Haplogroup D and its Subclades – 2008". Isogg.org. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Tajima, Atsushi; et al. (2004), "Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages", Journal of Human Genetics, 49 (4): 187–193, doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0131-x, PMID 14997363

- Y-Full

- Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Lalji Singh; Alla G. Reddy; V. Raghavendra Rao; Subhash C. Sehgal; Peter A. Underhill; Melanie Pierson; Ian G. Frame; Erika Hagelberg (2002), Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008, retrieved 16 November 2008,

... Our data indicate that the Andamanese have closer affinities to Asian than to African populations and suggest that they are the descendants of the early Palaeolithic colonizers of Southeast Asia ... All Onge and Jarawa had the same binary haplotype D ... Great Andaman males had five different binary haplotypes, found previously in Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and Melanesia ...

- Endicott, Phillip; Metspalu, Mait; Stringer, Chris; Macaulay, Vincent; Cooper, Alan; Sanchez, Juan J. (20 December 2006). "Multiplexed SNP Typing of Ancient DNA Clarifies the Origin of Andaman mtDNA Haplogroups amongst South Asian Tribal Populations". PLOS ONE. 1 (1): e81. Bibcode:2006PLoSO...1...81E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000081. PMC 1766372. PMID 17218991.

- Michael D. Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (2007), The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4,

... As haplogroup M, except for the African sub-clade M1, is not notably present in regions west of the Indian subcontinent, while it covers the majority of Indian mtDNA variation ...

- Rajkumar, Revathi; et al. (2005). "Phylogeny and antiquity of M macrohaplogroup inferred from complete mt DNA sequence of Indian specific lineages". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-26. PMC 1079809. PMID 15804362.

- Phillip Endicott; M. Thomas P. Gilbert; Chris Stringer; Carles Lalueza-Fox; Eske Willerslev; Anders J. Hansen; Alan Cooper (1 January 2002), "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders", American Journal of Human Genetics, The American Society of Human Genetics, 72 (1): 178–84, doi:10.1086/345487, PMC 378623, PMID 12478481,

... The high frequency of M2 is consistent with its greater age, and its distribution suggests that many of the populations viewed as the autochthons of India because of their cultural inheritance may also be genetic descendants of the early settlers of southern Asia ...

- Choi, Charles (22 September 2011), Now-Extinct Relative Had Sex with Humans Far and Wide, LiveScience

- Mondal, Mayukh (16 January 2019), "Approximate Bayesian computation with deep learning supports a third archaic introgression in Asia and Oceania", Nature Communications, 10 (1): 246, Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..246M, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08089-7, PMC 6335398, PMID 30651539

- Teixeira, Joao (17 June 2019), "Using hominin introgression to trace modern human dispersals", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PNAS, 116 (31): 15327–15332, doi:10.1073/pnas.1904824116, PMC 6681743, PMID 31300536

- Skoglund, P; Mallick, S; Patterson, N; Reich, D (2018). "No evidence for unknown archaic ancestry in South Asia". Nat Genet. 50: 632–633. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0097-9. PMC 6433599. PMID 29700470.

- Wall, Jeffrey D.; Ratan, Aakrosh; Stawiski, Eric; Wall, Jeffrey D.; Stawiski, Eric; Ratan, Aakrosh; Lim Kim, Hie; Kim, Changhoon; Gupta, Ravi; Suryamohan, Kushal; Gusareva, Elena S.; Wenang Purbojati, Rikky; Bhangale, Tushar; Stepanov, Vadim; Kharkov, Vladimir; Schrӧder, Markus S.; Ramprasad, Vedam; Tom, Jennifer; Durinck, Steffen; Bei, Qixin; Li, Jiani; Guillory, Joseph; Phalke, Samir; Basu, Analabha; Stinson, Jeremy; Nair, Sandhya; Malaichamy, Sivasankar; Biswas, Nidhan K.; Chambers, John C.; Cheng, Keith C.; George, Joyner T.; Soon Khor, Seik; Kim, Jong-Il; Cho, Belong; Menon, Ramesh; Sattibabu, Thiramsetti; Bassi, Akshi; Deshmukh, Manjari; Verma, Anjali; Gopalan, Vivek; Shin, Jong-Yeon; Pratapneni, Mahesh; Santhosh, Sam; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Md-Zain, Badrul M.; Gan Chan, Kok; Parani, Madasamy; Natarajan, Purushothaman; Hauser, Michael; Allingham, R. Rand; Santiago-Turla, Cecilia; Ghosh, Arkasubhra; Gopi Krishna Gadde, Santosh; Fuchsberger, Christian; Forer, Lukas; Shoenherr, Sebastian; Sudoyo, Herawati; Lansing, J. Stephen; Friedlaender, Jonathan; Koki, George; Cox, Murray P.; Hammer, Michael; Karafet, Tatiana; Ang, Khai C.; Mehdi, Syed Q.; Radha, Venkatesan; Mohan, Viswanathan; Majumder, Partha P.; Seshagiri, Sekar; Seo, Jeong-Sun; Schuster, Stephan; Peterson, Andrew S. (2019). "Identification of African-Specific Admixture between Modern and Archaic Humans". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 105: 1254–1261. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.11.005.

External links

- The Andamanese by George Weber

- News by Survival International

- Videos by Survival International