Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia

Alexei Nikolaevich (Russian: Алексе́й Никола́евич) (12 August 1904 [O.S. 30 July] – 17 July 1918) of the House of Romanov, was the last Tsesarevich[note 1] and heir apparent to the throne of the Russian Empire. He was the youngest child and only son of Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. He was born with haemophilia, which was treated by the faith healer Grigori Rasputin.[3]

| Alexei Nikolaevich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsesarevich of Russia | |||||

Alexei in 1913 | |||||

| Born | 12 August 1904 Peterhof Palace, St. Petersburg Governorate, Russian Empire | ||||

| Died | 17 July 1918 (aged 13) Ipatiev House, Yekaterinburg, Russian SFSR | ||||

| |||||

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov | ||||

| Father | Nicholas II of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Alix of Hesse | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

After the February Revolution of 1917, he and his family were sent into internal exile in Tobolsk, Siberia. Soon after the Bolsheviks took power, he and his entire family were executed, together with three retainers. This was ordered during the Russian Civil War by the Bolshevik government. Rumors persisted that he and a sister had survived until the 2007 discovery of his and one of his sisters' remains. On 17 July 1998, the eightieth anniversary of the execution, his parents and three sisters, along with their faithful retainers, were formally interred in the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul. Alexei and his sister Maria are still not buried. The family were canonized as passion bearers by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000.

He is sometimes known to Russian legitimists as Alexei II, as they do not recognize the abdication of his father in favor of his uncle Grand Duke Michael as lawful. Legitimists also refuse to recognise the abdication because it was not published by the Imperial Senate, as required by law.[4]

Biography

Early years

_with_his_sailor_nanny_Andrei_Dereven'ko_aboard_the_Imperial_yacht_Standart_on_June_1908.jpg)

Alexei was born on 12 August [O.S. 30 July] 1904 in Peterhof Palace, St. Petersburg Governorate, Russian Empire. He was the youngest of five children and the only son born to Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. His older sisters were the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia. He was doted on by his parents and sisters and known as "Baby" in the family. He was later also affectionately referred to as Alyosha (Алёша).

Alexei was christened on 3 September 1904 in the chapel in Peterhof Palace. His principal godparents were his paternal grandmother and his great-uncle, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich. His other godparents included his oldest sister, Olga; his great-grandfather King Christian IX of Denmark; King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, the Prince of Wales and William II, German Emperor. As Russia was at war with Japan, all active soldiers and officers of the Russian Army and Navy were named honorary godfathers.[5]

The christening marked the first time that some of the younger members of the Imperial Family, including some of the younger sons of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich; the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana; and their cousin Princess Irina Alexandrovna, attended an official ceremony. For the occasion, the boys wore miniature military uniforms, and the girls wore smaller versions of the court dress and little kokoshniks.[6] The sermon was delivered by John of Kronstadt. The baby was carried to the font by the elderly Princess Maria Mikhailovna Galitzine, Mistress of the Robes. As a precaution, she had rubber soles put on her shoes to prevent her slipping and dropping him.

Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden recalled:

The baby lay on a pillow of cloth of gold, slung to the Princess's shoulders by a broad gold band. He was covered with the heavy cloth-of-gold mantle, lined with ermine, worn by the heir to the crown. The mantle was supported on one side by Prince Alexander Sergeiovich Dolgorouky, the Grand Marshal of the Court, and on the other by Count [Paul] Benckendorff, as decreed by custom and wise precaution. The baby wept loudly, as might any ordinary baby, when old Father Yanishev dipped him in the font. His four small sisters, in short Court dresses, gazed open-eyed at the ceremony, Olga Nicholaevna, then nine years old, being in the important position of one of the godmothers. According to Russian custom, the Emperor and Empress were not present at the baptism, but directly after the ceremony the Emperor went to the church. Both he and the Empress always confessed to feeling very nervous on these occasions, for fear that the Princess might slip, or that Father Yanishev, who was very old, might drop the baby in the font.[7]

Hemophilia

Alexei inherited hemophilia from his mother Alexandra, a hereditary condition that affects males, which she had acquired through the line of her maternal grandmother Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. It was known as the "Royal Disease" because so many descendants of the intermarried European royal families had it (or carried it, in the case of females.) In 2009 genetic analysis determined that Alexei had suffered from hemophilia B.[8][9]

It was then known that people with hemophilia could bleed easily, and fatally. Alexei had to be protected because he lacked factor IX, one of the proteins necessary for blood-clotting. According to his French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, the nature of his illness was kept a state secret. His hemophilia was so severe that trivial injuries such as a bruise, a nosebleed or a cut were potentially life-threatening. Two navy sailors were assigned to him to monitor and supervise him to prevent injuries, which still took place. Sometimes the disease caused pain in his joints, and the sailors carried Alexei around when he was unable to walk. His parents constantly worried about him. In addition, the recurring episodes of illness and long recoveries interfered greatly with Alexei's childhood and education.[10]

In September 1912 the Romanovs were visiting their hunting retreat in the Białowieża Forest. On 5 September Alexei jumped into a rowboat, hitting of the oarlocks. A large bruise appeared within minutes but in a week reduced in size.[11] In mid-September the family moved to Spała (then in Russian Poland). On 2 October, after a drive in the woods, the "juddering of the carriage had caused still healing hematoma in his upper thigh to rupture and start bleeding again."[12] Alexei had to be carried out in an almost unconscious state. His temperature rose and his heartbeat dropped, caused by a swelling in the left groin; Alexandra barely left his bedside. A constant record was kept of the boy's temperature. On 10 October, a medical bulletin on his status was published in the newspapers, and Alexei was given the last sacrament.[13] According to the Tsar, the boy's condition improved at once. (According to historian M. Nelipa, Robert K. Massie was correct to suggest that psychological factors play a part in the course of the disease.)[14] The positive trend continued throughout the next day.[15] (About this time, either 9,[16] 10 or 11 October, the Tsarina asked her lady-in-waiting and best friend, Anna Vyrubova,[17][18] to secure the help of Rasputin, a peasant healer who was out of favor at the court.) According to his daughter, Rasputin received the telegram on 12 October[note 2] Rasputin responded to the Tsarina the next day with a short telegram,[20] saying: "The little one will not die. Do not allow the doctors [c.q. Eugene Botkin and Vladimir Derevenko] to bother him too much."[21] On 19 October Alexei's condition was much better and the hematoma disappeared. The boy had to undergo orthopedic therapy to straighten his left leg.[22]

According to Pierre Gilliard's 1921 memoir,

The Tsar had resisted the influence of Rasputin for a long time. At the beginning he had tolerated him because he dare not weaken the Tsarina's faith in him – a faith which kept her alive. He did not like to send him away for, if Alexei Nicolaievich had died, in the eyes of the mother he would have been the murderer of his own son.[23]

Observers and scholars have offered suggestions for Rasputin's apparent positive effect on Alexei: he used hypnotism, administered herbs to the boy, or his advice to prevent too much action by the doctors aided the boy's healing. Others speculated that, with the information he got from his confidante at the court, lady-in-waiting Anna Vyrubova, Rasputin timed his "interventions" for times when Alexei was already recovering, and claimed all the credit. Court physician Botkin believed that Rasputin was a charlatan and that his apparent healing powers were based on the use of hypnosis. But Rasputin did not become interested in this practice before 1913 and his teacher Gerasim Papandato was expelled from St. Petersburg.[24][25] Felix Yusupov, one of Rasputin's enemies, suggested that he secretly gave Alexei Tibetan herbs which he got from quack doctor Peter Badmayev, but these drugs were rejected by the court.[26][27] Maria Rasputin believed her father exercised magnetism.[28]

Writers from the 1920s had a variety of explanations for the apparent effects of Rasputin. Greg King thinks such explanations fail to take into account those times when Rasputin apparently healed the boy, despite being 2600 km (1650 miles) away. For historian Fuhrmann, these ideas on hypnosis and drugs flourished because the Imperial Family lived in such isolation from the wider world.[29] ("They lived almost as much apart from Russian society as if they were settlers in Canada."[29][30]) Moynahan says, "There is no evidence that Rasputin ever summoned up spirits, or felt the need to; he won his admirers through force of personality, not by tricks."[31] Shelley said that the secret of Rasputin's power lay in the sense of calm, gentle strength, and shining warmth of conviction.[32] Radzinsky wrote in 2000 that Rasputin believed he truly possessed a supernatural healing ability or that his prayers to God saved the boy.[33]

Gilliard,[34] the French historian Hélène Carrère d'Encausse[35] and Diarmuid Jeffreys, a journalist, speculated that Rasputin may have halted the administration of aspirin. This pain-relieving analgesic had been available since 1899 but would have worsened Alexei's condition.[36] Because aspirin is an antiaggregant and has blood-thinning properties; it prevents clotting, and promotes bleeding which could have caused the hemarthrosis. The "anti-inflammatory drug" would have worsened Alexei's joints' swelling and pain.[37][38]

Alexei and his sisters were taught by their mother to view Rasputin as "Our Friend" and to exchange confidences with him. Alexei understood that he might not live to adulthood. When he was ten, his older sister Olga found him lying on his back looking at the clouds and asked him what he was doing. "I like to think and wonder," Alexei replied. Olga asked him what he liked to think about. "Oh, so many things," the boy responded. "I enjoy the sun and the beauty of summer as long as I can. Who knows whether one of these days I shall not be prevented from doing it?"[39]

Childhood

According to his French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, Alexei was a simple, affectionate child, but the court spoiled him by the "servile flattery" of the servants and "silly adulations" of the people around him. Once, a deputation of peasants came to bring presents to Alexei. His personal attendant, the sailor Derevenko, required that they kneel before Alexei. Gilliard remarked that the Tsarevich was "embarrassed and blushed violently", and when asked if he liked seeing people on their knees before him, he said, "Oh no, but Derevenko says it must be so!" When Gilliard encouraged Alexei to "stop Derevenko insisting on it", he said that he "dare not". When Gilliard took the matter up with Derevenko, he said that Alexei was "delighted to be freed from this irksome formality".[40]

"Alexei was the center of this united family, the focus of all its hopes and affections," wrote Gilliard. "His sisters worshipped him. He was his parents' pride and joy. When he was well, the palace was transformed. Everyone and everything in it seemed bathed in sunshine."[41] He bore a striking resemblance to his mother, and was tall for his age, with "a long, finely chiseled face, delicate features, auburn hair with a coppery glint, and large grey-blue eyes like his mother,"[42] Though intelligent and affectionate, Alexei had frequent interruptions to his education, and he was spoiled because his parents couldn't bear to discipline him. His parents appointed two sailors from the Imperial Navy: Petty Officer Andrei Derevenko and his assistant Seaman Klementy Nagorny, to serve as nannies and to follow him about so he would not hurt himself.[43] He was prohibited from riding a bicycle or playing too roughly, but was naturally active.

As a small child, Alexei occasionally played pranks on guests. At a formal dinner party, Alexei removed the shoe of a female guest from under the table, and showed it to his father. Nicholas sternly told the boy to return the "trophy", which Alexei did after placing a large ripe strawberry into the toe of the shoe.[44]

Gilliard eventually convinced Alexei's parents that granting the boy greater autonomy would help him develop better self-control. Alexei took advantage of his unaccustomed freedom, and began to outgrow some of his earlier foibles.[45] Courtiers reported that his illness made him sensitive to the hurts of others.[46] During World War I, he lived with his father at army headquarters in Mogilev for long stretches of time and observed military life.[47] Alexei became one of the first Boy Scouts in Russia.[48][49]

In December 1916, Major-General Sir John Hanbury-Williams, head of the British military at Stavka, received word of the death of his son in action with the British Expeditionary Force in France. Tsar Nicholas sent twelve-year-old Alexei to sit with the grieving father. "Papa told me to come sit with you as he thought you might feel lonely tonight," Alexei told the general.[50] Alexei, like all the Romanov men, grew up wearing sailor uniforms and playing at war from the time he was a toddler. His father began to prepare him for his future role as Tsar by inviting Alexei to sit in on long meetings with government ministers.[46]

The Tsar's Colonel Mordinov remembered Alexei:

He had what we Russians usually call "a golden heart." He easily felt an attachment to people, he liked them and tried to do his best to help them, especially when it seemed to him that someone was unjustly hurt. His love, like that of his parents, was based mainly on pity. Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich was an awfully lazy, but very capable boy (I think, he was lazy precisely because he was capable), he easily grasped everything, he was thoughtful and keen beyond his years ... Despite his good nature and compassion, he undoubtedly promised to possess a firm and independent character in the future.[51]

Stavka

.jpg)

During World War I, Alexei joined his father at Stavka, when his father became the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army in 1915. Alexei seemed to like military life very much and became very playful and energetic. In one of his father's notes to his mother, he said "…Have come in from the garden with wet sleeves and boots as Alexei sprayed us at the fountain. It is his favorite game…peals of laughter ring out. I keep an eye, in order to see that things do not go too far." Alexei even ate the soldiers' black bread, and refused when he was offered a meal that he would eat in his palace, saying "It's not what soldiers eat". In December 1915, Rasputin was invited to see Alexei when the 11-year-old boy was accidentally thrown against the window of a train and his nose began to bleed.

In 1916, he was given the title of Lance Corporal, which he was very proud of. Alexei's favorites were the foreigners of Belgium, Britain, France, Japan, Italy, and Serbia, and in favor, adopted him as their mascot. Hanbury-Williams, whom Alexei liked, wrote: "As time went on and his shyness wore off he treated us like old friends and… had always some bit fun with us. With me it was to make sure that each button on my coat was properly fastened, a habit which naturally made me take great care to have one or two unbuttoned, in which case he used to at once to stop and tell me that I was 'untidy again,' give a sigh at my lack of attention to these details and stop and carefully button me up again."

Imprisonment of the Imperial family

The imperial family was arrested following the February Revolution of 1917, which resulted in the abdication of Nicholas II. When he was in captivity at Tobolsk, Alexei complained in his diary that he was "bored" and begged God to have "mercy" on him. He was permitted to play occasionally with Kolya, the son of one of his doctors, and with a kitchen boy named Leonid Sednev. As he became older, Alexei seemed to tempt fate and injure himself on purpose. While in Siberia, he rode a sled down the stairs of the prison house and injured himself in the groin. The hemorrhage was very bad, and he was so ill that he could not be moved immediately when the Bolsheviks relocated his parents and older sister Maria to Yekaterinburg in April 1918. However, neither Nicholas II nor Empress Alexandra mention anything about a sledding accident in their diaries, and in fact primary resources such as letters of Empress Alexandra and the diaries of both Nicholas II and Alexandra state that the haemorrhage was caused by a coughing fit.[52][53] On March 30 (12 April) 1918, Empress Alexandra recorded in her diary: 'Baby stays in bed as fr[om] coughing so hard has a slight haemorrhage in the abdom[en].[54] Everyday from then onwards until her removal to Ekaterinburg, Alexandra recorded Alexei's condition in her diary. Alexei and his three other sisters joined the rest of the family weeks later.[55] He was confined to a wheelchair for the remaining weeks of his life.

Death

The Tsesarevich was less than a month shy of his fourteenth birthday when he was executed on 17 July 1918 in the cellar room of the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg (which may also spelled as: Ekaterinburg). The assassination was carried out by forces of the Bolshevik secret police under Yakov Yurovsky. According to one account of the execution, the family was told to get up and get dressed in the middle of the night because they were going to be moved. Nicholas II carried Alexei to the cellar room. His mother asked for chairs to be brought so that she and Alexei could sit down. When the family and their servants were settled, Yurovsky announced that they were to be executed. The firing squad first killed Nicholas, the Tsarina, and the two male servants. Alexei remained sitting in the chair, "terrified," before the assassins turned on him and shot at him repeatedly. The boy remained alive and the killers tried to stab him multiple times with bayonets. "Nothing seemed to work," wrote Yurovsky later. "Though injured, he continued to live." Unbeknownst to the killing squad, the Tsarevich's torso was protected by a shirt wrapped in precious gems that he wore beneath his tunic. Finally Yurovsky fired two shots into the boy's head, and he fell silent.[56]

For decades (until all the bodies were found and identified, see below) conspiracy theorists suggested that one or more of the family somehow survived the slaughter. Several people claimed to be surviving members of the Romanov family following the assassinations. People who have pretended to be the Tsarevich include: Alexei Poutziato, Joseph Veres, Heino Tammet, Michael Goleniewski and Vassili Filatov. However, scientists considered it extremely unlikely that he escaped death, due to his lifelong hemophilia.

2007 remains found and 2008 identification of remains

On 23 August 2007, a Russian archaeologist announced the discovery of two burned, partial skeletons at a bonfire site near Yekaterinburg that appeared to match the site described in Yurovsky's memoirs. The archaeologists said the bones are from a boy who was roughly between the ages of ten and thirteen years at the time of his death and of a young woman who was roughly between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three years old.[57] Anastasia was seventeen years, one month old at the time of the assassination, while Maria was nineteen years, one month old. Alexei was two weeks shy of his fourteenth birthday. Alexei's elder sisters, Olga and Tatiana, were twenty-two and twenty-one years old, respectively, at the time of the assassination. Along with the remains of the two bodies, archaeologists found "shards of a container of sulfuric acid, nails, metal strips from a wooden box, and bullets of various caliber." The bones were found using metal detectors and metal rods as probes. Also, striped material was found that appeared to have been from a blue-and-white striped cloth; Alexei commonly wore a blue-and-white striped undershirt.

On 30 April 2008, Russian forensic scientists announced that DNA testing had proven that the remains belong to the Tsarevich Alexei and to one of his sisters.[58] DNA information, made public in July 2008, that was obtained from the Yekaterinburg site and repeated independent testing by laboratories such as the University of Massachusetts Medical School revealed that the final two missing Romanov remains were indeed authentic and that the entire Romanov family lived in the Ipatiev House. In March 2009, results of the DNA testing were published, confirming that the two bodies discovered in 2007 were those of Tsarevich Alexei and one of his sisters.[59][60]

Sainthood

The family had been canonized as holy martyrs in 1981 by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, which had developed among emigres after the Russian Revolution and the World Wars. After the decline of the Soviet Union, the government of Russia agreed with the Russian Orthodox Church to have the bodies of Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra, and three of their daughters (who were found at the execution site) interred at St. Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg on 17 July 1998, eighty years after they were executed. In 2000, Alexei and his family were canonized as passion bearers by the Russian Orthodox Church.

As noted, the remains of Alexei and a sister's bodies were found in 2008. As of 2015, Alexei's remains had not yet been interred with the rest of his family, as the Russian Orthodox Church has requested more DNA-testing to ensure that his identity was confirmed.[61]

Historical significance

Alexei was the heir apparent to the Romanov Throne. Paul I had passed laws forbidding women to succeed to the throne (unless there were no legitimate male dynasts left, in which case, the throne would pass to the closest female relative of the last Tsar). He had established this rule in revenge for what he perceived to have been the illegal behavior of his mother, Catherine II ("the Great"), in deposing his father Peter III.

Nicholas II was forced to abdicate on 15 March [O.S. 2 March] 1917. He did this in favour of his twelve-year-old son Alexei, who ascended the throne under a regency. Nicholas later decided to alter his original abdication. Whether that act had any legal validity is open to speculation. Nicholas consulted with doctors and others and realised that he would have to be separated from Alexei if he abdicated in favour of his son. Not wanting Alexei to be parted from the family in this crisis, Nicholas altered the abdication document in favour of his younger brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia. After receiving advice about whether his personal security could be guaranteed, Michael declined to accept the throne without the people's approval through an election held by the proposed Constituent Assembly. No such referendum was ever held.[62]

Grigori Rasputin rose in political power because the Tsarina believed that he could heal Alexei's hemophilia, or his attacks. Rasputin advised the Tsar that the Great War would be won once he (Tsar Nicholas II) took command of the Russian Army. Following this advice was a serious mistake, as the Tsar had no military experience. The Tsarina, Empress Alexandra, a deeply religious woman, came to rely upon Rasputin and believe in his ability to help Alexei where conventional doctors had failed. Historian Robert K. Massie explored this theme in his book, Nicholas and Alexandra.

Massie contends that caring for Alexei seriously diverted the attention of his father, Nicholas II, and the rest of the Romanovs from the business of war and government.[63]

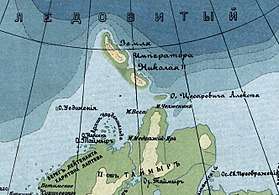

Tsarevich Alexei Island (Russian: Остров Цесаревича Алексея), later renamed Maly Taymyr, was named in honour of Alexei by the 1913 Arctic Ocean Hydrographic Expedition led by Boris Vilkitsky on behalf of the Russian Hydrographic Service.[64]

Honours

- Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-called, Knight, 11 August 1904

- Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, Knight, 11 August 1904

- Order of St. Anna, Knight 1st Class, 11 August 1904

- Order of St. Stanislaus, Knight 1st Class, 11 August 1904

- Imperial Order of the White Eagle, Knight, 11 August 1904

- St. George Medal, 4th Class, 17 October 1915

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The royal haemophilia line

Haemophilia in European royalty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend: X – unaffected X chromosome; x – affected X chromosome; Y – Y chromosome Source: Aronova-Tiuntseva, Yelena; Herreid, Clyde Freeman (20 September 2003). "Hemophilia: 'The Royal Disease'" (PDF). SciLinks. National Science Teachers Association. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2018. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Romanov impostors

Notes

- The title tsesarevich is most often confused with tsarevich, which is a distinct word with a different meaning: Tsarevich was the title for any son of a tsar, including sons of non-Russian rulers accorded that title, e.g. Crimea, Siberia, Georgia while Tsesarevich was the title reserved for the heirs of the Emperors of Russia after Peter I.[1][2]

- If Rasputin's daughter was right about the day - after eleven years - that her father responded -October 13th- "the longstanding claim that Rasputin had somehow alleviated Alexei's condition is simply fictitious."[19]

References

- Macedonsky, Dimitry (2005–2006). "Hail, Son of Caesar! A Titular History of Romanov Scions". European Royal History Journal. 8.3 (XLV): 19–27.

- Burke's Royal Families of the World II. Burke's Peerage Ltd. 1980. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-85011-029-6.

- "Alexis". Encloypaedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "The Abdication of Nicholas II: 100 Years Later". The Russian Legitimist. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, 1928.

- Christening of Alexei 1904 Archived 24 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Buxhoeveden, 1928.

- Michael Price (8 October 2009). "Case Closed: Famous Royals Suffered From Hemophilia". ScienceNOW Daily News. AAAS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Evgeny I. Rogaev; et al. (8 October 2009). "Genotype Analysis Identifies the Cause of the "Royal Disease"". Science. 326 (5954): 817. doi:10.1126/science.1180660. PMID 19815722. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Yegorov, O. (21 February 2018). "Royal diseases: 4 Russian rulers and heirs leveled by sickness". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- M. Nelipa (2015) Alexei. Russia's Last Imperial Heir: A Chronicle of Tragedy, pp. 76-77.

- Rappaport, p. 179.

- M. Nelipa (2015) ALEXEI, Russia's Last Imperial Heir: A Chronicle of Tragedy. Chapter III, p. 84.

- Robert K. Massie (1967) Nicholas and Alexandra, p. 15?

- M. Nelipa (2015) Alexei, pp. 85-86.

- Fuhrmann, p. 101.

- Vyrubova, p. 94

- Moe, p. 156.

- M. Nelipa (2015) Alexei, p. 90.

- M. Rasputin, The Real Rasputin, p. 72.

- Fuhrmann, pp. 100–101.

- M. Nelipa (2015) Alexei, p. 93.

- Gilliard, Pierre (1921). Thirteen Years at the Russian Court. Translated by F. Appleby Holt (3rd ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co. pp. 177–178. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Pares, p. 138.

- Fuhrmann, p. 103.

- "The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra – Chapter XV – A Mother's Agony – Rasputin"

- Moe, p. 152.

- Rasputin, p. 33.

- Bernard Pares (6 January 1927) "Rasputin and the Empress: Authors of the Russian Collapse", Foreign Affairs.etrieved on 15 July 2014.

- Rappaport, p. 117.

- Moynahan, p. 165.

- G. Shelley (1925), The Speckled Domes. Episodes of an Englishman's life in Russia, p. 60.

- Edvard Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, Doubleday, 2000, p. 77

- Le Précepteur des Romanov by Daniel GIRARDIN Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- H.C. d'Encausse (1996) Nicolas II, La transition interrompue, p. 147, (Fayard) ; Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia.

- Diarmuid Jeffreys (2004). Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Lichterman, B. L. (2004). "Aspirin: The Story of a Wonder Drug". BMJ. 329 (7479): 1408. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1408. PMC 535471.

- HEROIN® and ASPIRIN® The Connection! & The Collection! - Part II By Cecil Munsey

- Massie, p. 143

- "Pierre Gilliard – Thirteen Years at the Russian Court – memoirs of Nicholas, Alexandra and their family – Influence of Rasputin – Vyrubova – My Tutorial Troubles". alexanderpalace.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, 1967, p. 137.

- Massie, p. 144

- Kurth, Peter, "Tsar: the lost world of Nicholas and Alexandra", Allen & Unwin, 1998, p. 74, ISBN 1-86448-911-1

- Massie, pp. 136–143

- Massie, p. 145

- Massie, pp. 136–146

- Massie, p. 296

- Biography of Pantuhin on side pravoverie.ru Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "NATIONAL ORGANISATION OF RUSSIAN SCOUTS-Who Are We ?". National Organisation of Russian Scouts (N.O.R.S.). Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- Massie, p. 307.

- Zeepvat, Charlotte, The Camera and the Tsars: A Romanov Family Album, Sutton Publishing Limited, 2004, p. 20

- Vyrubova, Memories of the Russian Court, p 338, letter of Empress Alexandra to Ania Vyrubova

- Nicholas II 1918 Diary March 30, 31 (old style)

- The Last Diary of Tsaritsa Alexandra, Yale University Press 1997

- King and Wilson, pp. 83–84

- King and Wilson, pp. 309–310

- Bones found by Russian builder finally solve riddle of the missing Romanovs by Luke Harding of The Guardian (UK)

- Eckel, Mike (2008). "DNA confirms IDs of czar's children". yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Details on the testing of the Imperial remains are contained in Rogaev, E.I., Grigorenko, A.P., Moliaka, I.K., Faskhutdinova, G., Goltsov,A., Lahti, A., Hildebrandt, C., Kittler, E.L.W. and Morozova, I., "Genomic identification in historical case of Nicholas II Royal family.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (2009). The mitochondrial DNA of Alexandra, Alexei, and Maria are identical and of haplogroup H1. The mitochondrial DNA of Nicholas was haplogroup T2. Their sequences are published at GenBank as FJ656214, FJ656215, FJ656216, and FJ656217.

- "DNA proves Bolsheviks killed all of Russian Czar's children", CNN (11 March 2009)

- Luhn, Alec (11 September 2015). "Russia agrees to further testing over 'remains of Romanov children'". The Guardian.

- Kerensky, A. F. (1927), The Catastrophe, Chapter 1, Marxists Internet Archive

- Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, 1967

- Barr, William (1975). "Severnaya Zemlya: the last major discovery". Geographical Journal. 141 (1): 59–71. doi:10.2307/1796946. JSTOR 1796946.

- Russian Imperial Army - Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich (In Russian)

- M. & B. Wattel (2009). Les Grand'Croix de la Légion d'honneur de 1805 à nos jours. Titulaires français et étrangers. Paris: Archives & Culture. p. 520. ISBN 978-2-35077-135-9.

- Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1915, p. 671, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1918) page 81

- Alexander II, Emperor of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Alexander III, Emperor of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. Heiligenberg: Our Ardently Loved Hill. Published in Royalty Digest. No 49. July 1995.

- "Christian IX". The Danish Monarchy. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Vammen, Tinne (15 May 2003). "Louise (1817–1898)". Dansk Biografisk Leksikon (in Danish).

- Willis, Daniel A. (2002). The Descendants of King George I of Great Britain. Clearfield Company. p. 717. ISBN 978-0-8063-5172-8.

- Gelardi, Julia P. (1 April 2007). Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria. St. Martin's Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781429904551. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Ludwig Clemm (1959), "Elisabeth", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 444–445; (full text online)

- Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1999). Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. London: Little, Brown. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85605-469-0.

Further reading

- Greg King and Penny Wilson, The Fate of the Romanovs, John Wiley and Sons, 2003, ISBN 0-471-20768-3

- Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, 1967.

- Robert K. Massie, The Romanovs: The Final Chapter, Random House, 1995, ISBN 0-394-58048-6

- Andrei Maylunas and Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion: Nicholas and Alexandra: Their Own Story, Doubleday, 1997, ISBN 0-385-48673-1

- Edvard Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, Doubleday, 2000, ISBN 0-385-48909-9

- Demetrios Serfes, A Miracle Through the Prayers of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarevich Alexis

- Maxim Shevchenko, The Glorification of the Royal Family, a 2000 article in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta

- Charlotte Zeepvat, The Camera and the Tsars: A Romanov Family Album, Sutton Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3049-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexei Nikolaievich of Russia. |