Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, DBE (née Miller; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English writer known for her sixty-six detective novels and fourteen short story collections, particularly those revolving around fictional detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple. She also wrote the world's longest-running play The Mousetrap, performed in the West End since 1952, as well as six novels under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. In 1971, she was appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for her contribution to literature.

Dame Agatha Christie Lady Mallowan DBE | |

|---|---|

Agatha Christie in 1925 | |

| Born | Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller 15 September 1890 Torquay, Devon, England |

| Died | 12 January 1976 (aged 85) Winterbrook House, Winterbrook, Oxfordshire, England |

| Resting place | Church of St Mary, Cholsey, Oxfordshire, England |

| Pen name | Mary Westmacott |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet, memoirist |

| Genre | Murder mystery, detective story, crime fiction, thriller |

| Literary movement | Golden Age of Detective Fiction |

| Notable works | Creation of characters Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, Murder on the Orient Express, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Death on the Nile, The Murder at the Vicarage, Partners in Crime, The A.B.C. Murders, And Then There Were None, The Mousetrap |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | James Watts (nephew) |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| agathachristie | |

Christie was born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family in Torquay, Devon. She served in a Devon hospital during the First World War, acquiring a good knowledge of poisons which would later feature in many of her novels, short stories, and plays. She was initially an unsuccessful writer with six consecutive rejections, but this changed when The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920 featuring Hercule Poirot. Following her second marriage in 1930 to an archaeologist, she used her first-hand knowledge of her husband's profession in her fiction. During the Second World War, she worked as a pharmacy assistant at University College Hospital, London, updating her knowledge of toxins while contributing to the war effort.

Guinness World Records lists Christie as the best-selling novelist of all time. Her novels have sold roughly 2 billion copies, and her estate claims that her works come third in the rankings of the world's most-widely published books, behind only Shakespeare's works and the Bible. According to Index Translationum, she remains the most-translated individual author, having been translated into at least 103 languages. And Then There Were None is Christie's best-selling novel, with 100 million sales to date, making it the world's best-selling mystery ever and one of the best-selling books of all time. Christie's stage play The Mousetrap holds the world record for longest initial run. It opened at the Ambassadors Theatre in the West End on 25 November 1952, and by September 2018 there had been more than 27,500 performances.

In 1955, Christie was the first recipient of the Mystery Writers of America's Grand Master Award. Later that year, Witness for the Prosecution received an Edgar Award for best play. In 2013, she was voted the best crime writer and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd the best crime novel ever by 600 professional novelists of the Crime Writers' Association. In September 2015, coinciding with her 125th birthday, And Then There Were None was named the "World's Favourite Christie" in a vote sponsored by the author's estate. Most of Christie's books and short stories have been adapted for television, radio, video games, and comics, and more than thirty feature films have been based on her work.

Life and career

Childhood and adolescence: 1890–1910

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born on 15 September 1890 into a wealthy upper-middle-class family in Torquay, Devon. She was the youngest of three children born to Frederick Alvah ("Fred") Miller, "a gentleman of substance",[1]:16 and his wife Clarissa Margaret ("Clara") Miller née Boehmer.[2]:1–4[3][4][5]

Christie's mother Clara was born in Dublin in 1854[lower-alpha 1][6][7] to Lieutenant (later Captain) Frederick Boehmer (91st Regiment of Foot)[8] and his second wife Mary Ann Boehmer née West. Boehmer died aged 49 of bronchitis[lower-alpha 2] in Jersey in April 1863, leaving his widow to raise Clara and her three brothers alone on a meagre income.[12] Two weeks after Boehmer's death, Mary's sister Margaret West married widowed dry goods merchant Nathaniel Frary Miller, a US citizen.[13] To assist Mary financially, the newlyweds agreed to foster nine-year old Clara. The family settled in Timperley, Cheshire.[14] Margaret and Nathaniel had no children together, but Nathaniel had a seventeen-year-old son, Fred Miller, from his previous marriage. Fred was born in New York City and travelled extensively after leaving his Swiss boarding school. He and Clara eventually formed a romantic attachment and were married in St Peter's Church, Notting Hill, in April 1878.[2]:2–5[3]

Fred and Clara's first child, Margaret Frary ("Madge"), was born in Torquay in 1879,[15] where the couple were renting lodgings. Their second child, Louis Montant ("Monty"), was born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1880[16] while they were making an extended visit to the United States. When Fred's father died in 1869,[17] he left Clara £2,000; they used this money to purchase the leasehold of a villa in Torquay named Ashfield in which to raise their family. It was here that their third and final child, Agatha, was born in 1890.[2]:6–7[5]

Christie described her childhood as "very happy".[9]:3 She was surrounded by a series of strong and independent women from an early age.[2]:14 She lived primarily in Devon, but would visit the homes of her step-grandmother/great-aunt Margaret Miller in Ealing and maternal grandmother Mary Boehmer in Bayswater. One year of her childhood was spent abroad with her family, in the French Pyrenees, Paris, Dinard, and Guernsey.[2]:15,24–25

Christie was raised in a household with esoteric beliefs and, like her siblings, believed that her mother Clara was a psychic with the ability of second sight.[2]:13 Christie's sister Madge had been sent to Roedean School in Sussex for her education, but their mother insisted that Christie receive a home education. As a result, her parents were responsible for teaching her to read and write and to master basic arithmetic, a subject she particularly enjoyed. They also taught her music, and she learned to play both the piano and the mandolin.[2]:20–21 According to one biographer, Clara believed that Christie should not learn to read until she was eight. However, thanks to her own curiosity, Christie taught herself to read much earlier.[11]:18 One of the earliest known photographs of Christie depicts her as a little girl with her first dog, named George Washington by her patriotic father but which she called Tony.[9]:20–21,42

Christie was a voracious reader from an early age. Among her earliest memories were those of reading the children's books written by Mrs Molesworth, including The Adventures of Herr Baby (1881), Christmas Tree Land (1897), and The Magic Nuts (1898). She also read the work of Edith Nesbit, including The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899), The Phoenix and the Carpet (1903), and The Railway Children (1906). When a little older, she moved on to reading the surreal verse of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll.[2]:18–19 In April 1901, at age 10, she wrote her first poem, "The cowslip".[18]

Although she devoted much time to her pets, Christie spent much of her childhood apart from other children. She eventually made friends with a group of other girls in Torquay, noting that "one of the highlights of my existence" was her appearance with them in a youth production of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Yeomen of the Guard, in which she played the hero, Colonel Fairfax.[2]:23–27 This was her last operatic role for, as she later wrote, "an experience that you really enjoyed should never be repeated."[9]:114

By 1901, Christie's father's health had deteriorated, due to what he believed were heart problems.[11]:33 Fred died in November 1901 from pneumonia and chronic kidney disease.[19] The family's financial situation had by this time declined significantly. Christie and her mother Clara continued to live in their Torquay home. Christie's sister Madge married the year after their father's death and moved to Cheadle, (historic county of) Cheshire. Christie's brother Monty was overseas, serving in a British regiment. Christie later said that her father's death, occurring when she was 11 years old, marked the end of her childhood.[2]:32–34

In 1902, Christie began attending Miss Guyer's Girls' School in Torquay but found it difficult to adjust to the disciplined atmosphere. In 1905, she was sent to Paris where she was educated in three pensions – Mademoiselle Cabernet's, Les Marroniers, and then Miss Dryden's – the last of which served primarily as a finishing school.[2]:22–23,37

Early literary attempts and the First World War: 1910–1919

After completing her education, Christie returned to England and found her mother ailing. They decided to spend time together in the warmer climate of Cairo, then a regular tourist destination for wealthy Britons. They stayed for three months at the Gezirah Palace Hotel. Christie attended many social functions and particularly enjoyed watching polo. She visited ancient Egyptian monuments such as the Great Pyramid of Giza, but did not exhibit the great interest in archaeology and Egyptology that became prominent in her later years.[2]:40–41 Returning to Britain, she continued her social activities, writing and performing in amateur theatricals. She also helped put on a play called The Blue Beard of Unhappiness with female friends. Her writing extended to both poetry and music. Some early works saw publication, but she decided against focusing on writing or music as future professions.[2]:45–47

Christie wrote her first short story, The House of Beauty (an early version of her later-published story The House of Dreams,[20]) while recovering in bed from an undisclosed illness. This was about 6,000 words on the topic of "madness and dreams", a subject of fascination for her. One of her biographers has commented that, despite "infelicities of style", the story was nevertheless "compelling".[2]:48–49 Other stories followed, most of them illustrating her interest in spiritualism and the paranormal. These included "The Call of Wings" and "The Little Lonely God". Magazines rejected all her early submissions, made under pseudonyms (including Mac Miller, Nathaniel Miller, and Sydney West), although some submissions were revised and published later, often with new titles.[2]:49–50

Christie then set her first novel, Snow Upon the Desert, in Cairo and drew from her recent experiences in that city, writing under the pseudonym Monosyllaba. She was disappointed when the six publishers she contacted all declined.[2]:50–51[21] Clara suggested that her daughter ask for advice from a family friend and neighbour, successful novelist Eden Phillpotts, who responded to her enquiry, encouraged her writing, and sent her an introduction to his own literary agent, Hughes Massie, who rejected Snow Upon the Desert and suggested a second novel.[2]:51–52 Meanwhile, her social activities expanded. She entered into short-lived relationships with four separate men and an engagement with another.[11]:64–67 She then met Archibald Christie at a dance given by Lord and Lady Clifford at Ugbrooke, about 12 miles (19 kilometres) from Torquay. Archie was born in India, the son of a barrister in the Indian Civil Service. He was an army officer who was seconded to the Royal Flying Corps in April 1913. The couple quickly fell in love. Upon learning that he would be stationed in Farnborough, Archie proposed marriage, and Agatha accepted.[2]:54–63

With the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Archie was sent to France to fight the German forces. They married on the afternoon of Christmas Eve 1914 at Emmanuel Church, Clifton, Bristol, which was close to the home of his mother and stepfather, while Archie was on home leave.[22][23] Rising through the ranks, he was eventually stationed back to Britain in September 1918 as a colonel in the Air Ministry. Christie involved herself in the war effort as a member of the Voluntary Aid Detachment of the Red Cross. From October 1914 to May 1915, then from June 1916 to September 1918, she worked a total of 3400 hours in the Town Hall Red Cross Hospital, Torquay, first as a nurse (unpaid) then as a dispenser (at £16 a year from 1917) after qualifying as an apothecaries' assistant.[2]:69[24] Her war service ended when Archie was reassigned to London, and they rented a flat in St. John's Wood.[2]:73–74

First novels and Poirot: 1919–1926

Christie had long been a fan of detective novels, having enjoyed Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White and The Moonstone, as well as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's early Sherlock Holmes stories. She wrote her own detective novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, featuring Hercule Poirot, a former Belgian police officer noted for his twirly large "magnificent moustaches" and egg-shaped head. Poirot had taken refuge in Britain after Germany invaded Belgium. Christie's inspiration for the character stemmed from real Belgian refugees who were living in Torquay and the Belgian soldiers whom she helped to treat as a volunteer nurse in Torquay during the First World War.[2]:75–79[25]:17–18 She began working on The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1916, writing much of it on Dartmoor.[18] Her original manuscript was rejected by such publishing companies as Hodder and Stoughton and Methuen. After keeping the submission for several months, John Lane at The Bodley Head offered to accept it, provided that Christie changed how the solution was revealed. She did so, and signed a contract which she later felt was exploitative.[2]:79,81–82 It was finally published in 1920.[18]

Christie, meanwhile, settled into married life, giving birth to her only child, Rosalind Margaret Clarissa, in August 1919 at Ashfield.[2]:79[11]:340,349,422 Archie left the Air Force at the end of the war and started working in the City financial sector at a relatively low salary, though they still employed a maid.[2]:80–81 Her second novel, The Secret Adversary (1922), featured a new detective couple Tommy and Tuppence, again published by The Bodley Head. It earned her £50. A third novel again featured Poirot, Murder on the Links (1923), as did short stories commissioned by Bruce Ingram, editor of The Sketch magazine.[2]:83

In 1922, the Christies joined an around-the-world promotional tour for the British Empire Exhibition, led by Major Ernest Belcher. Leaving their daughter with Agatha's mother and sister, in ten months they travelled to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Canada.[2]:86–103[26] They learned to surf prone in South Africa; then, in Waikiki, they were among the first Britons to surf standing up.[27][28]

Following their return to England, Archie resumed work in the City, while Christie continued to work hard at her writing. After a series of apartments in London, they moved to the country, eventually purchasing a house in Sunningdale, Berkshire, which they renamed Styles after the mansion in Christie's first detective novel.[2]:124–125[11]:154–155

Christie's mother died in April 1926. They had been exceptionally close, and the loss sent Christie into a deep depression.[11]:168–172 In late summer 1926, reports appeared in the press that Christie had gone to a village near Biarritz to recuperate from a "breakdown" caused by "overwork".[29]

Disappearance: 1926

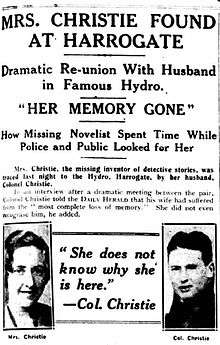

In August 1926, Archie asked Christie for a divorce. He had fallen in love with Nancy Neele, who had been a friend of Major Belcher. On 3 December 1926, the pair quarrelled after Archie announced his plan to spend the weekend with friends, unaccompanied by his wife. Late that evening, Christie disappeared from her home. Her Morris Cowley car was found at Newlands Corner, perched above a chalk quarry with an expired driving licence and clothes.[2]:135[30][31]

The disappearance caused a public outcry. Home secretary William Joynson-Hicks pressured police, and a newspaper offered a £100 reward. Over a thousand police officers, 15,000 volunteers, and several aeroplanes scoured the rural landscape. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave a spirit medium one of Christie's gloves to find her.[lower-alpha 3] Christie's disappearance was featured on the front page of The New York Times. Despite the extensive manhunt, she was not found for ten days.[33][32][34] On 14 December 1926, she was found at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel[35] in Harrogate, Yorkshire, registered as Mrs Tressa[lower-alpha 4] Neele (the surname of her husband's lover) from "Capetown S.A." (South Africa). The next day, Christie left for her sister's residence at Abney Hall, Cheadle, where she was sequestered "in guarded hall, gates locked, telephone cut off, and callers turned away."[2]:146[11]:196[36]:1,4,9[37]:1

Christie's autobiography makes no reference to the disappearance.[9] Two doctors diagnosed her as suffering from "an unquestionable genuine loss of memory",[37]:1[38]:12 yet opinion remains divided over the reason for her disappearance. Some believe that she disappeared during a fugue state, including her biographer Janet Morgan.[2]:154–159[32][39] In contrast, Jared Cade's research led him to conclude that Christie deliberately planned the event to embarrass her husband, but did not anticipate the public melodrama that resulted.[40]:121 Laura Thompson provides the alternative view that Christie disappeared during a nervous breakdown, conscious of her actions but not in emotional control of herself.[11]:220–221 Public reaction at the time was largely negative, supposing a publicity stunt or an attempt to frame her husband for murder.[41][lower-alpha 5]

Second marriage and later life: 1927–1976

In January 1927, Christie, looking "very pale", sailed with her daughter and secretary to Las Palmas, Canary Islands, to "complete her convalescence",[42] returning three months later.[43][lower-alpha 6] Christie petitioned for divorce and was granted a decree nisi against her husband in April 1928 which was made absolute in October 1928. Archie married Nancy Neele a week later.[44] Christie retained custody of their daughter Rosalind and the Christie surname for her writing. During their marriage, she published six novels, a collection of short stories, and a number of short stories in magazines.[45]

Some years later, reflecting on the whole period, Christie said, "So, after illness, came sorrow, despair and heartbreak. There is no need to dwell on it."[9]:340

In autumn 1928, Christie left England and took the (Simplon) Orient Express to Istanbul; she subsequently went on to Baghdad. In Iraq, she became friends with archaeologist Leonard Woolley and his wife, who invited her to return to their dig in February 1930. On that second trip, she met a young archaeologist 13 years her junior,[46] Max Mallowan. In a 1977 interview, Mallowan recounted his first meeting with Christie, when he took her and a group of tourists on a tour of his expedition site in Iraq.[47] Christie and Mallowan married in September 1930.[2]:178–179[11]:284–285[48] Their marriage was happy and lasted until Christie's death in 1976.[11]

Christie frequently used settings that were familiar to her for her stories. She typically accompanied Mallowan on his archaeological expeditions, and her travels with him contributed background to several of her novels set in the Middle East.[47] Other novels (such as And Then There Were None) were set in and around Torquay, where she was raised. Christie's 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express was written in the Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul, Turkey, the southern terminus of the railway. The hotel maintains Christie's room as a memorial to the author.[49]

The Greenway Estate in Devon, acquired by the couple as a summer residence in 1938, is now in the care of the National Trust. Christie frequently stayed at Abney Hall, Cheshire, owned by her brother-in-law, James Watts, basing at least two stories there: a short story "The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding" in the story collection of the same name, and the novel After the Funeral. One Christie compendium notes that "Abney became Agatha's greatest inspiration for country-house life, with all its servants and grandeur being woven into her plots. The descriptions of the fictional Chimneys, Stoneygates, and other houses in her stories are mostly Abney Hall in various forms."[50]

During the Second World War, Christie worked in the pharmacy at University College Hospital (UCH), London, where she acquired a knowledge of poisons that she put to good use in her post-war crime novels. For example, the use of thallium as a poison was suggested to her by UCH Chief Pharmacist Harold Davis (later appointed Chief Pharmacist at the Ministry of Health), and in The Pale Horse, published in 1961, she employed it to dispatch a series of victims, the first clue to the murder method coming from the victims' loss of hair. So accurate was her description of thallium poisoning that it helped solve a case that was baffling doctors.[51][52]

Christie lived in Chelsea, first in Cresswell Place and later in Sheffield Terrace. Both properties are now marked by blue plaques. In 1934, she and Max Mallowan purchased Winterbrook House in Winterbrook, a hamlet adjoining the small market town of Wallingford, then within the bounds of Cholsey and in Berkshire.[53] This was their main residence for the rest of their lives and the place where Christie did much of her writing.[11]:365 This house, too, bears a blue plaque. Christie led a quiet life despite being known in the town of Wallingford,[54] where she was for many years President of the local amateur dramatic society.[55]

The British intelligence agency MI5 investigated Christie after a character called Major Bletchley appeared in her 1941 thriller N or M?, which was about a hunt for a pair of deadly fifth columnists in wartime England.[56] MI5 was concerned that Christie had a spy in Britain's top-secret codebreaking centre, Bletchley Park. The agency's fears were allayed when Christie told her friend, the codebreaker Dilly Knox, "I was stuck there on my way by train from Oxford to London and took revenge by giving the name to one of my least lovable characters."[56]

In honour of her many literary works, Christie was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1956 New Year Honours.[57] The next year, she became the President of the Detection Club.[58] In the 1971 New Year Honours, she was promoted to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE),[59][60][61] three years after her husband had been knighted for his archaeological work in 1968.[62] They were one of the few married couples where both partners were honoured in their own right. From 1968, owing to her husband's knighthood, Christie could also be styled Lady Mallowan.

From 1971 to 1974, Christie's health began to fail, although she continued to write. Recently, using experimental tools of textual analysis, Canadian researchers have suggested that Christie may have begun to suffer from Alzheimer's disease or other dementia.[63][64][65][66]

Personal qualities

%2C_bij_aankomst_op_Schiphol_me%2C_Bestanddeelnr_916-8898_(cropped).jpg)

In 1946, Christie said of herself: "My chief dislikes are crowds, loud noises, gramophones and cinemas. I dislike the taste of alcohol and do not like smoking. I DO like sun, sea, flowers, travelling, strange foods, sports, concerts, theatres, pianos, and doing embroidery."[67]

Although Christie's works of fiction contain some objectionable character stereotypes, in real life many of her biases were positive. After four years of war-torn London, Christie hoped to return some day to Syria, which she described as "gentle fertile country and its simple people, who know how to laugh and how to enjoy life; who are idle and gay, and who have dignity, good manners, and a great sense of humour, and to whom death is not terrible."[68]:167

The Agatha Christie Trust For Children commenced in 1969[69] and shortly after Christie's death a charitable memorial fund was set up to "help two causes that she favoured: old people and young children."[70]

Christie's obituary in The Times notes that "she never cared much for the cinema, or for wireless and television". Further,

Dame Agatha's private pleasures were gardening – she won local prizes for horticulture – and buying furniture for her various houses. She was a shy person: she disliked public appearances: but she was friendly and sharp-witted to meet. By inclination as well as breeding she belonged to the English upper middle-class. She wrote about, and for, people like herself. That was an essential part of her charm.[1]

Death and estate

Christie's death and burial

Christie died peacefully on 12 January 1976 at age 85 from natural causes at her home Winterbrook House, Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire.[54][71] At the time of her death Winterbrook was still a part of the parish of Cholsey. She was buried in the nearby churchyard of St Mary's, Cholsey, having chosen the plot for their final resting place with her husband Sir Max some ten years before she died. The simple funeral service was attended by about 20 newspaper and TV reporters, some having travelled from as far away as South America. Thirty wreaths adorned Christie's grave, including one from the cast of her long-running play The Mousetrap and one sent "on behalf of the multitude of grateful readers" by the Ulverscroft Large Print Book Publishers.[72]

Sir Max Mallowan, who remarried in 1977, died in 1978 and was interred next to Christie.[73]

Christie's estate and subsequent ownership of works

Although Christie was rather unhappy about becoming "an employed wage slave",[11]:428 to avoid future adverse tax implications she set up a private company, Agatha Christie Limited, in 1955 to hold the rights to her works, and in about 1959 transferred her 278-acre home, Greenway Estate, to her daughter Rosalind.[74][75] In 1968, when Christie was almost 80 years old, she sold a 51% stake in Agatha Christie Limited (and therefore the works it owned) to Booker Books (better known as Booker Author's Division), a subsidiary of the British food and transport conglomerate Booker-McConnell (now Booker Group), the founder of the Booker Prize for literature, which by 1977 had increased its stake to 64%.[2]:355[76] Agatha Christie Limited remains the owner of the worldwide rights for over eighty of Christie's novels and short stories, nineteen plays, and nearly forty TV films.[77]

In the late 1950s, Christie had reputedly been earning around £100,000 per year but, as a result of her tax planning, her will left only £106,683 net which went mostly to her husband and daughter along with some smaller bequests.[54][78] Her remaining 36% share of Agatha Christie Limited was inherited by her daughter, Rosalind Hicks, who passionately preserved her mother's works, image, and legacy until her own death 28 years later.[74] The family's share of the company allowed them to appoint 50% of the board and the chairman, and thereby to retain a veto over new treatments, updated versions, and republications of her works.[74][79]

In 2004, Hicks' obituary in The Telegraph commented that she had been "determined to remain true to her mother's vision and to protect the integrity of her creations" and disapproved of "merchandising" activities.[74] Upon her death on 28 October 2004, both the Greenway Estate passed to her son Mathew Prichard. After his step-father's death in 2005, Prichard donated Greenway and its contents to the National Trust.[74][80]

Christie's family and family trusts, including James Prichard, continue to own the 36% stake in Agatha Christie Limited,[77] and remain associated with the company. In 2020, James Prichard was the company's chairman.[81] Mathew Prichard also holds the copyright to some of his grandmother's later literary works (including The Mousetrap).[11]:427 Christie's work continues to be developed in a range of adaptations.[82]

In 1998, Booker sold a number of its non-food assets to focus on its core business. As part of that, its shares in Agatha Christie Limited (at the time earning £2.1m annual revenue) were sold for £10m to Chorion, a major international media company whose portfolio of well-known authors' works also included the literary estates of Enid Blyton and Dennis Wheatley.[79] In February 2012, some years after a management buyout, Chorion found itself in financial difficulties, and began to sell off its literary assets on the market.[77] The process included the sale of Chorion's 64% stake in Agatha Christie Limited to Acorn Media UK[83] In 2014, RLJ Entertainment Inc. acquired Acorn Media UK, renamed it Acorn Media Enterprises, and incorporated it as the RLJE UK development arm.[84]

In late February 2014, media reports stated that the BBC had acquired exclusive TV rights to Christie's works in the UK (previously associated with ITV) and made plans with Acorn's co-operation to air new productions for the 125th anniversary of Christie's birth in 2015.[85] As part of that deal, the BBC broadcast Partners in Crime[86] and And Then There Were None,[87] both in 2015. Subsequent productions have included The Witness for the Prosecution[88] but plans to televise Ordeal by Innocence at Christmas 2017 were delayed due to controversy surrounding one of the cast members.[89] The three-part adaptation aired in April 2018.[90] A three-part adaptation of The A.B.C. Murders starring John Malkovich and Rupert Grint began filming in June 2018 for later broadcast.[91]

Works, reception and legacy

Works of fiction

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple

Christie's first book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, was published in 1920 and introduced the detective Hercule Poirot, who became a long-running character in Christie's works, appearing in thirty-three novels and fifty-four short stories.[25][92]

Miss Jane Marple was introduced in a series of short stories that began publication in December 1927 and were subsequently collected under the title The Thirteen Problems.[11]:278 Although Christie states that "Miss Marple was not in any way a picture of my grandmother; she was far more fussy and spinsterish than my grandmother ever was", her autobiography does establish a firm connection between the fictional character and Christie's step-grandmother Margaret Miller ("Auntie-Grannie")[lower-alpha 7] and her "Ealing cronies".[9]:422–423[93] Both Marple and Miller "always expected the worst of everyone and everything, and were, with almost frightening accuracy, usually proved right".[9]:422 Marple appeared in twelve novels and twenty stories.

During the Second World War, Christie wrote two novels, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, intended as the last cases of these two great detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple. Both books were sealed in a bank vault for over thirty years and were released for publication by Christie only at the end of her life, when she realised that she could not write any more novels. These publications came on the heels of the success of the film version of Murder on the Orient Express in 1974.[9]:497[94]

Christie became increasingly tired of Poirot, much as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had grown weary of his character Sherlock Holmes. By the end of the 1930s, Christie wrote in her diary that she was finding Poirot "insufferable", and by the 1960s she felt that he was "an egocentric creep".[95]

Unlike Conan Doyle, Christie resisted the temptation to kill her detective off while he was still popular. She saw herself as an entertainer whose job was to produce what the public liked, and the public liked Poirot.[96] She did marry off Poirot's companion Captain Hastings in an attempt to trim her cast commitments.[9]:268

In contrast, Christie was fond of Miss Marple. However, the Belgian detective's titles outnumber the Marple titles more than two to one. This is largely because Christie wrote numerous Poirot novels early in her career, while The Murder at the Vicarage remained the sole Marple novel until the 1940s. Christie never wrote a novel or short story featuring both Poirot and Miss Marple. In a recording discovered and released in 2008, Christie revealed the reason for this: "Hercule Poirot, a complete egoist, would not like being taught his business or having suggestions made to him by an elderly spinster lady. Hercule Poirot – a professional sleuth – would not be at home at all in Miss Marple's world".[93] However, Three Act Tragedy does feature both Hercule Poirot and the elderly bachelor Mr. Satterthwaite (confederate of Harley Quin).[97]

Anticipating the publication of Curtain, Poirot became the first fictional character to be covered on the front page of The New York Times when his obituary was printed there on 6 August 1975.[98]

Following the great success of Curtain, Christie gave permission for the release of Sleeping Murder sometime in 1976 but died in January 1976 before the book could be published. This may explain some of the inconsistencies compared to the rest of the Marple series; for example, Colonel Arthur Bantry, husband of Miss Marple's friend Dolly, is still alive and well in Sleeping Murder although he is noted as having died in books published earlier. It may be that Christie simply did not have time to revise the manuscript before she died.[99]

In 2013, the Christie family gave their "full backing" to the release of a new Poirot story, The Monogram Murders, which was written by British author Sophie Hannah.[100] Hannah later released two more Poirot mysteries, Closed Casket, in 2016[101] and The Mystery of the Three-Quarters in 2018.

Formula and plot devices

Early in Christie's career, a reporter noted that "her plots are possible, logical, and always new".[29] According to Sophie Hannah, "At the start of each novel, she shows us an apparently impossible situation and we go mad wondering 'How can this be happening?' Then, slowly, she reveals how the impossible is not only possible but the only thing that could have happened."[101]

The "Queen of Fictional Crime"[102] developed her storytelling techniques during what has been called the Golden Age of detective fiction. Dilys Winn dubbed Christie "the doyenne of Coziness", a sub-genre which "featured a small village setting, a hero with faintly aristocratic family connections, a plethora of red herrings and a tendency to commit homicide with sterling silver letter openers and poisons imported from Paraguay".[103] At the end, in a Christie hallmark, the detective usually gathers the surviving suspects into one room, explains the course of his or her deductive reasoning, and reveals the guilty party, although there are exceptions in which it is left to the guilty party to explain all (such as And Then There Were None and Endless Night).[104][105]

Christie did not limit herself to quaint English villages – the action might take place on a small island (And Then There Were None), an aeroplane (Murder in the Clouds), a train (Murder on the Orient Express), a steamship (Death on the Nile), a smart London flat (Cards on the Table), a resort in the West Indies (A Caribbean Mystery), or an archaeological dig (Murder in Mesopotamia) – but the circle of potential suspects is nonetheless usually closed and intimate: family members, friends, servants, business associates, fellow travellers.[106]:37 Stereotyped characters abound (the vamp, the stolid policeman, the devoted servant, the dull colonel), but these may be subverted to stymie the reader; impersonations and secret alliances are always possible.[106]:58 There is always a motive – most often, money: "There are very few killers in Christie who enjoy murder for its own sake".[11]:379,396

Professor of Pharmacology Michael C. Gerald noted that "in over half her novels, one or more victims are poisoned, albeit not always to the full satisfaction of the perpetrator".[107] Guns, knives, garrotes, tripwires, the classic blunt instrument, and even a hatchet were also employed, but "Christie never resorted to elaborate mechanical or scientific means to explain her ingenuity",[108]:57 according to author and "longtime literary adviser"[109] to the Christie estate John Curran. Many of her clues are mundane objects: a calendar, a coffee cup, wax flowers, a beer bottle, a fireplace used during a heat wave.[106]:38

In some stories, the question remains unresolved as to whether formal justice will ever be delivered, such as Five Little Pigs and Endless Night. According to P. D. James, Christie was prone to making the unlikeliest character the guilty party. Savvy readers could sometimes identify the culprit by simply identifying the least likely suspect.[110] Christie herself mocked this insight in her Forward to Cards on the Table: "Spot the person least likely to have committed the crime and in nine times out of ten your task is finished. Since I do not want my faithful readers to fling away this book in disgust, I prefer to warn them beforehand that this is not that kind of book."[111]:135–136

On an edition of Desert Island Discs in 2007, Brian Aldiss said that Christie had told him that she wrote her books up to the last chapter, then decided who the most unlikely suspect was, after which she would go back and make the necessary changes to "frame" that person.[112] Based upon a study of her working notebooks, however, John Curran describes how Christie would first create a cast of characters, choose a setting, and then produce a list of scenes in which specific clues would be revealed; the order of scenes would be revised as she further developed her plot. Of necessity, the murderer had to be known to the author before the sequence could be finalised and she began to type or dictate the first draft of her novel.[106] Much of the work, particularly dialogue, was done in her head before she began to put it down on paper.[9]:241–245[111]:33

Her most famous novel is emblematic of both her use of formula and her willingness to discard it. "And Then There Were None carries the 'closed society' type of murder mystery to extreme lengths", according to author Charles Osborne.[113]:170 Although it begins with the classic set-up of potential victim(s) and killer(s) isolated from the outside world, the book proceeds to violate conventions: There is no detective involved in the action, no interviews of suspects, no careful search for clues, and no suspects gathered together in the last chapter to be confronted with the solution. As Christie herself said, "Ten people had to die without it becoming ridiculous or the murderer being obvious."[9]:457 Critics agreed that she had succeeded: "The arrogant Mrs. Christie this time set herself a fearsome test of her own ingenuity ... the reviews, not surprisingly, were without exception wildly adulatory."[113]:170–171 In September 2015, to mark her 125th birthday, And Then There Were None was named the "World's Favourite Christie" in a vote sponsored by the author's estate.[114]

Two years earlier, the 600 members of the Crime Writers' Association had chosen the equally ingenious The Murder of Roger Ackroyd as "the best whodunit novel ever written".[115] Author Julian Symons said, "In an obvious sense, the book fits within the conventions ... The setting is a village deep within the English countryside, Roger Ackroyd dies in his study; there is a butler who behaves suspiciously ... Every successful detective story in this period involved a deceit practiced upon the reader, and here the trick is the highly original one of making the murderer the local doctor, who tells the story and acts as Poirot's Watson."[116]:106–107 Critic Sutherland Scott stated, "If Agatha Christie had made no other contribution to the literature of detective fiction she would still deserve our grateful thanks" for writing this novel.[117]

Titles

Many of Christie's mature works, from 1940 onward, have titles drawn from literature, with the original context of the title typically printed as an epigraph.[118]

Christie's inspirations for her titles include:

- William Shakespeare's works: Sad Cypress, By the Pricking of My Thumbs, There is a Tide..., Absent in the Spring, and The Mousetrap, for example. Author Charles Osborne notes that "Shakespeare is the writer most quoted in the works of Agatha Christie".[113]:164

- The Bible: Evil Under the Sun, The Burden, and The Pale Horse

- Other works of literature: The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side (from Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott"), The Moving Finger (from Edward FitzGerald's translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám), The Rose and the Yew Tree (from T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets), Postern of Fate (from James Elroy Flecker's "Gates of Damascus"), Endless Night (from William Blake's Auguries of Innocence), N or M? (from the Book of Common Prayer), and Come, Tell Me How You Live (from Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass).

Christie biographer Gillian Gill said that "Christie's writing has the sparseness, the directness, the narrative pace, and the universal appeal of the fairy story, and it is perhaps as modern fairy stories for grown-up children that Christie's novels succeed."[111]:208 Reflecting a juxtaposition of innocence and horror, numerous Christie titles were drawn from well-known children's nursery rhymes: And Then There Were None (from "Ten Little Indians"), One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (from "One, Two, Buckle My Shoe"), Five Little Pigs (from "This Little Piggy"), Crooked House (from "There Was a Crooked Man"), A Pocket Full of Rye (from "Sing a Song of Sixpence"), Hickory Dickory Dock (from "Hickory Dickory Dock"), and Three Blind Mice (from "Three Blind Mice"). Similarly, the novel Mrs McGinty's Dead is named after a children's game that is explained in the course of the story.

Character stereotypes

Christie would insert stereotyped descriptions of characters into her work, particularly before the end of the Second World War (when such attitudes were more commonly expressed publicly), and particularly in regard to Italians, Jews, and non-Europeans.[2]:264–266 For example, she described "men of Hebraic extraction, sallow men with hooked noses, wearing rather flamboyant jewellery" in the short story "The Soul of the Croupier" from the collection The Mysterious Mr Quin. In 1947, the Anti-Defamation League in the US sent an official letter of complaint to Christie's American publishers, Dodd, Mead and Company, regarding perceived antisemitism in her works. Christie's British literary agent later wrote to her US representative, authorising American publishers to "omit the word 'Jew' when it refers to an unpleasant character in future books".[11]:386

In The Hollow, published as late as 1946, one of the more unsympathetic characters is "a Whitechapel Jewess with dyed hair and a voice like a corncrake ... a small woman with a thick nose, henna red and a disagreeable voice". To contrast with the more stereotyped descriptions, Christie portrayed some "foreign" characters as victims, or potential victims, at the hands of English malefactors, such as, respectively, Olga Seminoff (Hallowe'en Party) and Katrina Reiger (in the short story "How Does Your Garden Grow?"). Jewish characters are often seen as un-English (such as Oliver Manders in Three Act Tragedy), but they are rarely the culprits.[119]

Plays

.jpg)

In 1928, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was adapted for the stage by Michael Morton under the title Alibi.[2]:177 While the play enjoyed a respectable run, Christie disliked the changes made to her original work and, in future, preferred to write for the theatre herself. The first of her own stage works was Black Coffee, which received good reviews when it opened in the West End in late 1930.[11]:277,301 She followed this up with adaptations of her detective novels: And Then There Were None in 1943, Appointment with Death in 1945, and The Hollow in 1951.[2]:242,251,288

In the 1950s, "it was the theatre that engaged much of Agatha's attention".[11]:360 She next adapted her own short radio play into The Mousetrap, which premiered in the West End in 1952, produced by Peter Saunders. Her own expectations for the play were not high; she believed it would run no more than eight months.[9]:500 It has long since made theatrical history, staging its 27,500th performance in September 2018.[120][121][122][123] In 1953, she followed this triumph with another critical and popular success, Witness for the Prosecution; the Broadway production won the New York Drama Critics' Circle award for best foreign play of 1954 and earned Christie an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America.[2]:300[108]:262 Spider's Web, an original work written specifically for actress Margaret Lockwood at her request, premiered in 1954 and was also a hit.[2]:297,300

Christie said that, "Plays are much easier to write than books, because you can see them in your mind's eye, you are not hampered by all that description which clogs you so terribly in a book and stops you from getting on with what's happening."[9]:459 In a letter to her daughter, Christie said that being a playwright was "a lot of fun!"[11]:474

As Mary Westmacott

Christie published six mainstream novels under the name Mary Westmacott, a pseudonym that gave her the freedom to explore "her most private and precious imaginative garden".[11]:366–367 These books typically received better reviews than her detective and thriller fiction; of the first, Giant's Bread published in 1930, a New York Times reviewer wrote, "... her book is far above the average of current fiction, in fact, comes well under the classification of a 'good book.' And it is only a satisfying novel that can claim that appellation."[124] After her authorship of the first four Westmacott novels was revealed by a journalist in 1949, she wrote only two more, the last in 1956.[11]:366

The other Westmacott titles are: Unfinished Portrait (1934), Absent in the Spring (1944), The Rose and the Yew Tree, (1948), A Daughter's a Daughter, (1952), and The Burden (1956).

Non-fiction works

Christie published relatively few non-fiction works:

- Come, Tell Me How You Live, about working on an archaeological dig, drawn from her life with second husband Max Mallowan

- The Grand Tour: Around the World with the Queen of Mystery, a collection of correspondence from her 1922 Grand Tour of the British empire, including South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada

- Agatha Christie: An Autobiography, published posthumously in 1977 and adjudged the Best Critical / Biographical Work at the 1978 Edgar Awards.[125]

Critical reception and legacy

Regularly referred to as the "Queen of Crime" or "Queen of Mystery", Christie is the world's best-selling mystery writer and is considered a master of suspense, plotting, and characterisation.[126][127][128] In 1955, Christie became the first recipient of the Mystery Writers of America's Grand Master Award.[125] In 2013, she was voted "best crime writer" in a survey of 600 members of the Crime Writers’ Association of professional novelists.[115] Some critics, however, have regarded Christie's plotting as superior to her skill with other literary elements. Novelist Raymond Chandler criticised her in his essay "The Simple Art of Murder", and American literary critic Edmund Wilson was dismissive of Christie and the detective fiction genre generally in his New Yorker essay, "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?"[129]

In 2012, Christie was among the people selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork, the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, to celebrate the British cultural figures of his lifetime whom he most admired.[130][131]

In 2015, in honour of the 125th anniversary of her birth, twenty-five contemporary mystery writers and one publisher revealed their views on Christie's works. Many of the authors had read Christie's novels first, before other mystery writers, in English or in their native language, influencing their own writing, and nearly all still viewed her as the "Queen of Crime" and creator of the plot twists used by mystery authors. Nearly all had one or more favourites among Christie's mysteries, and found her books still good to read nearly 100 years after her first novel was published. Just one of the twenty-five authors held with Edmund Wilson's views.[132]

In 2016, one hundred years after Christie wrote her first detective story, the Royal Mail released six stamps in her honour, featuring The Mysterious Affair at Styles, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Murder on the Orient Express, And Then There Were None, The Body in the Library, and A Murder is Announced. The Guardian reported that "Each design incorporates microtext, UV ink and thermochromic ink. These concealed clues can be revealed using either a magnifying glass, UV light or body heat and provide pointers to the mysteries' solutions."[133]

Guinness World Records lists Christie as the best-selling novelist of all time. Her novels have sold roughly 2 billion copies, and her estate claims that her works come third in the rankings of the world's most-widely published books,[134] behind only Shakespeare's works and the Bible. Half of the sales are of English language editions, and the other half in translation.[135] According to Index Translationum, she remains the most-translated individual author, having been translated into at least 103 languages.[136] And Then There Were None is Christie's best-selling novel, with 100 million sales to date, making it the world's best-selling mystery ever, and one of the best-selling books of all time.[137]

Adaptations

Christie's works have been adapted for both the big screen and television. The first was the 1928 British film The Passing of Mr. Quin. Poirot's first film appearance was in 1931 in Alibi, which starred Austin Trevor as Christie's sleuth.[138]:14–18 Margaret Rutherford starred as Marple in a series of films released in the 1960s. Although Christie personally liked the actress, she considered the first film "pretty poor" and thought no better of the rest.[11]:430–431

She felt differently about the 1974 film Murder on the Orient Express, directed by Sidney Lumet, which featured major stars and high production values; her attendance at the London premiere was one of her last public outings.[11]:476,482[138]:57 In 2016, a new film version was released, directed by Kenneth Branagh, who also starred, adorned by "the most extravagant mustache moviegoers have ever seen".[139]

Notable television adaptations include:

- Agatha Christie's Poirot, with David Suchet in the title role, which ran for 70 episodes over 13 series, 1989–2013, and was nominated for and won various BAFTA awards in 1990–1992[140]

- Miss Marple, with Joan Hickson as "the BBC's peerless Miss Marple", which adapted all twelve Marple novels 1984–1992[11]:500

- Les Petits Meurtres d'Agatha Christie (in French), including a four-part mini-series (2006) and a run of two series: 2009–2012 and 2013–2019, which adapted thirty-six of Christie's works of detective fiction.[141]

Interests and influences

Pharmacology

In the midst of the First World War, Christie took a break from nursing to train for the Apothecaries Hall Examination. While she subsequently found dispensing in the hospital pharmacy monotonous, and thus less enjoyable than nursing, her new knowledge provided her with a solid background in potentially toxic drugs. Early in the Second World War, she brought her skills up-to-date at Torquay Hospital.[9]:235,470

As Michael C. Gerald puts it, her "activities as a hospital dispenser during both World Wars not only supported the war effort but also provided her with an appreciation of drugs as therapeutic agents and poisons … These hospital experiences were also likely responsible for the prominent role physicians, nurses, and pharmacists play in her stories".[107]:viii There were to be many medical practitioners, pharmacists and scientists, naïve or suspicious, in Christie's future: Murder in Mesopotamia, Cards on the Table, The Pale Horse, and Mrs. McGinty's Dead, among numerous others.[107]

Gillian Gill also notes that the murder method in Christie's very first detective novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, "comes right out of Agatha Christie's work in the hospital dispensary."[111]:34 In an interview with journalist Marcelle Bernstein, Christie stated, "I don't like messy deaths … I'm more interested in peaceful people who die in their own beds and no one knows why."[142] With her expert knowledge, Christie had no need of poisons unknown to science, which were forbidden under Ronald Knox's "Ten Rules for Detective Fiction".[108]:58 Arsenic, aconite, strychnine, digitalis, thallium, and many other standard pharmaceuticals were utilised to dispatch victims in the ensuing decades.[107]

Archaeology

– Agatha Christie, 1977[9]:364

Christie had a lifelong interest in archaeology. She met her second husband, Max Mallowan, a distinguished archaeologist, on a trip to the excavation site at Ur in 1930. But her fame as an author far surpassed his fame in archaeology.[143] Prior to meeting Mallowan, Christie had not had any extensive brushes with archaeology, but once the two married, they made sure to only go to sites where they could work together. Christie accompanied Mallowan on countless archaeological trips, spending three to four months at a time in Syria and Iraq at excavation sites at Ur, Nineveh, Tell Arpachiyah, Chagar Bazar, Tell Brak, and Nimrud. She wrote novels and short stories, but also contributed work to the archaeological sites, more specifically to the archaeological restoration and labelling of ancient exhibits, including tasks such as cleaning and conserving delicate ivory pieces, reconstructing pottery, developing photos from early excavations which later led to taking photographs of the site and its findings, and taking field notes.[144]

Christie would always pay for her own board and lodging and her travel expenses so as to not influence the funding of the archaeological excavations, and she also supported excavations as an anonymous sponsor.[144] During their time in the Middle East, there was also a large amount of time spent travelling to and from Mallowan's sites. Their extensive travelling was reflected in novels such as Murder on the Orient Express, as well as suggesting the idea of archaeology as an adventure itself.[145]

After the Second World War, she chronicled her time in Syria with fondness in Come Tell Me How You Live. Anecdotes, memories, funny episodes are strung in a rough timeline, with more emphasis on eccentric characters and lovely scenery than on factual accuracy.[146] From 8 November 2001 to 24 March 2002, The British Museum had an exhibit named Agatha Christie and Archaeology: Mystery in Mesopotamia, which presented the life of Christie and the influences of archaeology in her life and works.[144]

Many of the settings for Christie's books were directly inspired by the numerous archaeological field seasons spent in the Middle East on the sites managed by her husband Max. The extent of her time spent at the many locations featured in her books is apparent from the extreme detail in which she describes them, such as the temple of Abu Simbel, depicted in Death on the Nile.[2]:212 Similarly, throughout Murder in Mesopotamia she draws upon her knowledge of daily life on a dig.[106]:269 Among the characters in her books, Christie has given prominence to the archaeologists and experts in Middle Eastern cultures and artefacts, most notably Dr. Eric Leidner in Murder in Mesopotamia and Signor Richetti in Death on the Nile; several minor characters are archaeologists in They Came to Baghdad.

Some of Christie's best known novels with strong archaeological influences are:

- Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) – set in the Middle East at an archaeological dig site and its associated expedition house. The main characters include archaeologist Dr. Eric Leidner, his wife, many specialists and assistants, and the men working on the site.

- Death on the Nile (1937) – takes place on a tour boat on the Nile. Many archaeological sites are visited along the way and one of the main characters, Signor Richetti, is an archaeologist.

- Appointment with Death (1938) – set in Jerusalem and the surrounding area. The eponymous death occurs at an old cave site in Petra and Christie provides some very descriptive details of sites which she may have visited.

- They Came to Baghdad (1951) – involves an archaeologist as the heroine's love interest.

Portrayals

Christie has been portrayed in film and television. Biographical programmes have been made, such as BBC television's Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures (2004; in which she was portrayed by Olivia Williams, Anna Massey, and Bonnie Wright, at different stages in her life), and in Season 3, Episode 1 of ITV Perspectives: "The Mystery of Agatha Christie" (2013), hosted by David Suchet, who plays Hercule Poirot on television.[147]

Christie has also been portrayed fictionally. Some of these portrayals have explored and offered accounts of Christie's disappearance in 1926, including:

- the film Agatha (1979) with Vanessa Redgrave, in which she sneaks away to plan revenge against her husband (Christie's heirs sued unsuccessfully to prevent the film's distribution[148]);

- the Doctor Who episode "The Unicorn and the Wasp" (17 May 2008), with Fenella Woolgar, in which her disappearance is the result of her suffering a temporary breakdown owing to a brief psychic link being formed between her and an alien wasp called the Vespiform; and

- Agatha and the Truth of Murder (2018), in which she goes under cover to solve the murder of Florence Nightingale's goddaughter, Florence Nightingale Shore.

A fictionalised account of Christie's disappearance is also the central theme of a Korean musical, Agatha.[149]

Other portrayals, such as Hungarian film, Kojak Budapesten (1980; not to be confused with the 1986 comedy of the same name) create their own scenarios involving Christie's criminal skill. In the TV play, Murder by the Book (1986), Christie herself (Dame Peggy Ashcroft) murdered one of her fictional-turned-real characters, Poirot. The heroine of Liar-Soft's visual novel Shikkoku no Sharnoth: What a Beautiful Tomorrow (2008), Mary Clarissa Christie, is based on the real-life Christie. Christie features as a character in Gaylord Larsen's Dorothy and Agatha and The London Blitz Murders by Max Allan Collins.[150][151] A young Agatha is depicted in the Spanish historical television series Gran Hotel (2011). Aiding the local detectives, Agatha finds inspiration to write her new novel. In the alternative history television film Agatha and the Curse of Ishtar (2018), Christie becomes involved in a murder case at an archaeological dig in Iraq.

See also

- Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures (Christie's life story in a 2004 BBC drama)

- Abney Hall (home to Christie's brother-in-law; several books use Abney as their setting)

- Greenway Estate (Christie's former home in Devon, now in the possession of the National Trust and open to the public)

- Agatha Christie bibliography (lists of Christie's works)

- Adaptations of Agatha Christie (Christie's work in other media)

- Agatha Christie indult (an oecumenical request to which Christie was signatory seeking permission for the occasional use of the Tridentine (Latin) mass in England and Wales)

- Agatha Awards (literary awards for mystery and crime writers)

- Agatha Christie Award (Japan) (literary award for unpublished mystery novels)

- Agatha Christie (video game series) (a series of adventure games based on Christie's works)

- List of solved missing persons cases

Notes

- Most biographers give Christie's mother's place of birth as Belfast but do not provide sources. Current primary evidence, including census entries (place of birth Dublin), her baptism record (March 1854, garrison chapel Dublin), and her father's service record and Regimental histories (for when her father was in Dublin), indicates she was almost certainly born in Dublin in the first Quarter of 1854.

- Christie's biographers have consistently claimed he was killed in a riding accident.[9]:5[10][2]:2[11]:9–10

- Crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers visited the "scene of the disappearance" and used the scenario in her book Unnatural Death.[32]

- The notice placed by Christie in The Times (11 December 1926, p.1) gives the first name as Teresa, but her hotel register signature more naturally reads Tressa and newspapers also reported that Christie used Tressa on other occasions during her disappearance.

- Christie herself hinted at a nervous breakdown, saying to a woman with similar symptoms, "I think you had better be very careful; it is probably the beginning of a nervous breakdown."[9]:337

- Christie's authorised biographer includes an account of specialist psychiatric treatment following Christie's disappearance, but the information was obtained at second- or third-hand after her death."[2]:148–149,159

- Christie's familial relationship to Margaret Miller née West was complex. From the information provided earlier in the article it can be seen that as well as Christie's maternal great-aunt, Miller was Christie's father's step-mother as well as Christie's mother's foster mother and step-mother-in-law – hence the appellation "Auntie-Grannie".

References

- "Obituary. Dame Agatha Christie". The Times. 13 January 1976. p. 16.

- Morgan, Janet P. (1984). Agatha Christie: A Biography. London, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-216330-9. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Marriage Register. St Peter's Church, Bayswater [Notting Hill], Middlesex, 1878, No. 399, p. 200.

- Birth Certificate. General Register Office (England & Wales), 1890 September Quarter, Newton Abbot, volume 5b, page 151. [Christie's forenames were not registered.]

- Baptism Register. Parish of Tormohun, Devon, 1890, No. 267, [n.p.].

- 1871 England Census. Class: RG10; Piece: 3685; Folio: 134; Page: 44

- Statement of Services: Frederick Boehmer, 91st Foot. The National Archives, Kew. WO 76/456, page 57. [Also states his daughter Clarissa Margaret was baptised in Dublin.]

- Goff, Gerald Lionel Joseph (1891). Historical records of the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders, now the 1st Battalion Princess Louise's Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, containing an account of the Regiment in 1794, and of its subsequent services to 1881. R. Bentley. pp. 218–219, 322.

- Christie, Agatha (1977). Agatha Christie: An Autobiography. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 0-396-07516-9.

- Robyns, Gwen (1978). The Mystery of Agatha Christie. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. p. 13.

- Thompson, Laura (2008), Agatha Christie: An English Mystery, London, UK: Headline Review, ISBN 978-0-7553-1488-1

- Burials in the Parish of St Helier, in the Island of Jersey. 1863. p. 303.

- Marriage Register. Parish of Westbourne, Sussex, 1863, No. 318, p. 159.

- Naturalisation Papers: Miller, Nathaniel Frary, from the United States. Certificate 4798 issued 25 August 1865. The National Archives, Kew. HO 1/123/4798.

- Birth Certificate. General Register Office (England & Wales), 1879 March Quarter, Newton Abbot, volume 5b, page 162.

- "Births". London Evening Standard. 26 June 1880. p. 1.

- Death Certificate. General Register Office (England & Wales), 1869 June Quarter, Westbourne, volume 02B, page 230.

- The Mystery of Agatha Christie – A Trip With David Suchet (Directed by Claire Lewins). Testimony films (for ITV).

- Death Certificate. General Register Office (England & Wales), 1901 December Quarter, Brentford, volume 3A, page 71. ("Cause of Death. Bright's disease, chronic. Pneumonia. Coma and heart failure.")

- The House of Dreams: Details, agathachristie.com. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Curran, John. "75 facts about Christie". agathachristie.com. Agatha Christie Limited. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- Curtis, Fay (24 December 2014). "Desert Island Doc: Agatha Christie's wartime wedding". Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Marriage Register. Parish of Emmanuel, Clifton, 1914, No. 305, p. 153.

- "Agatha Christie | British Red Cross". British Red Cross. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Fitzgibbon, Russell H. (1980). The Agatha Christie Companion. Bowling Green, Ohio: The Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- Prichard, Mathew (2012). The Grand Tour: Around The World With The Queen Of Mystery. New York City: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-219122-9.

- Jones, Sam (29 July 2011). "Agatha Christie's Surfing Secret Revealed". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Agatha Christie 'one of Britain's first stand-up surfers'". The Daily Telegraph. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "A Penalty of Realism". The Evening News. Portsmouth, Hampshire. 20 August 1926. p. 6.

- Hobbs, James. "Agatha's Disappearance". Hercule Poirot Central. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Christie's Life: 1925–1928 A Difficult Start". Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Thorpe, Vanessa (15 October 2006). "Christie's most famous mystery solved at last". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Mrs Christie Found in a Yorkshire Spa". The New York Times. 15 December 1926. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Agatha Christie's Harrogate mystery". BBC News. 3 December 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "The Details of this Strange Case…". www.classiclodges.co.uk. 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "What We Want to Know about Mrs. Christie". The Leeds Mercury. 16 December 1926.

- "What We Want to Know about Mrs. Christie". The Leeds Mercury. 17 December 1926.

- "Mrs Christie. Doctors Certify Loss of Memory". Western Daily Press. 17 December 1926. p. 12.

- "Dissociative Fugue". Psychology Today. 17 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Cade, Jared (1997), Agatha Christie and the Missing Eleven Days, Peter Owen, ISBN 0-7206-1112-1

- Adams, Cecil (2 April 1982), "Why did mystery writer Agatha Christie mysteriously disappear?", The Chicago Reader, retrieved 19 May 2008

- "Mrs. Christie Leaves". Daily Herald. 24 January 1927. p. 1.

- Inwards Passenger Lists. The National Archives, Kew. Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors, BT26/837/112.

- "Col. Christie Married". Gloucestershire Echo. 6 November 1928. p. 5. [Includes divorce details].

- "Agatha (Mary Clarissa) Christie". Gale. Gale. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "FreeBMD Entry Info". freebmd.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Interview with Max Mallowan". BBC. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- Marriage Certificate. Scotland – Statutory Register of Marriages, 685/04 0938, 11 September 1930, District of St Giles, Edinburgh.

- "Agatha Christie's Hotel Pera Palace in Istanbul, Turkey". Virtual Globetrotting. 6 June 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Wagstaff, Vanessa; Poole, Stephen (2004), Agatha Christie: A Reader's Companion, Aurum Press, p. 14, ISBN 1-84513-015-4

- "Thallium poisoning in fact and in fiction". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 277: 648. 25 November 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- John Emsley, "The poison prescribed by Agatha Christie", The Independent, 20 July 1992.

- Oxfordshire Blue Plaques, oxfordshireblueplaques.org.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "1976: Crime writer Agatha Christie dies". BBC on this Day. 12 January 1976. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Sinodun Players". sinodunplayers.org.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Richard Norton-Taylor (4 February 2013). "Agatha Christie was investigated by MI5 over Bletchley Park mystery". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". The London Gazette (Supplement: 40669). 30 December 1955. p. 11.

- "Biography: Agatha Christie", Authors, Illiterarty, retrieved 22 February 2009

- "D.B.E." The London Gazette (Supplement: 45262). 31 December 1970. p. 7.

- Kastan, David Scott (2006). The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-19-516921-8.

- Reitz, Caroline (2006), "Christie, Agatha", The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195169218.001.0001/acref-9780195169218-e-0098, ISBN 978-0-19-516921-8

- "Knights Bachelor". The London Gazette (Supplement: 44600). 31 May 1968. p. 6300.

- Kingston, Anne (2 April 2009), "The ultimate whodunit", Maclean's, Canada, retrieved 28 August 2009

- Boswell, Randy (6 April 2009), "Study finds possible dementia for Agatha Christie", Ottawa Citizen, retrieved 28 August 2009

- Devlin, Kate (4 April 2009). "Agatha Christie 'had Alzheimer's disease when she wrote final novels'". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Flood, Alison (3 April 2009). "Study claims Agatha Christie had Alzheimer's". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- "The Real Agatha Christie". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 April 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Christie Mallowan, Agatha (1990) [1946]. Come, Tell Me How You Live. London, UK: Fontana Books. ISBN 0-00-637594-4.

- "Data for financial year ending 05 April 2018 – The Agatha Christie Trust For Children". Registered charities in England and Wales. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Agatha Christie memorial fund". The Times. 27 April 1976. p. 16.

- "Deaths". The Times. 14 January 1976. p. 26.

- Yurdan, Marilyn (2010). Oxfordshire Graves and Gravestones. Stroud, United Kingdom: The History Press. ISBN 9780752452579.

- "St. Marys Cholsey | Agatha Christie". www.stmaryscholsey.org. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Obituary: Rosalind Hicks, The Daily Telegraph, 13 November 2004. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "1976: Crime writer Agatha Christie dies". BBC on this Day. 12 January 1976. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Booker is ready for more". The Newcastle Journal. 16 September 1977. p. 4.

- Acorn Media buys stake in Agatha Christie estate, The Guardian, 29 December 2012.

- "£106,000 will of Dame Agatha Christie". The Times. 1 May 1976. p. 2.

- Agatha Christie begins new chapter after £10m selloff, TheFreeLibrary.com, 4 June 1998.

- "The Big Question: How big is the Agatha Christie industry, and what explains her enduring appeal?". The Independent. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "About Agatha Christie Limited". The Home of Agatha Christie. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Why do we still love the 'cosy crime' of Agatha Christie?". The Independent. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Sweney, Mark (29 February 2012). "Acorn Media buys stake in Agatha Christie estate". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "RLJ Entertainment". rljentertainment.com. 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "New era for BBC as the new home of Agatha Christie adaptations", Radio Times, 28 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "BBC One – Partners in Crime – Episode Guide". BBC. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Staff (28 December 2015). "BBC One – And Then There Were None". BBC. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "BBC One - The Witness for the Prosecution". BBC. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Ed Westwick removed from BBC Agatha Christie drama Ordeal By Innocence". BBC News. 5 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "BBC One – Ordeal by Innocence". BBC. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "All-star cast announced for new BBC One Agatha Christie thriller The ABC Murders". BBC. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Hercule Poirot Reading List" (PDF). AgathaChristie.com. Agatha Christie Limited. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Mills, Selina (15 September 2008). "Dusty clues to Christie unearthed". BBC News. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- susanvaughan (25 January 2018). "Dame Agatha and Her Orient Express". Maine Crime Writers. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Gross, John (2006). The New Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0199543410.

- "Agatha Christie – Her Detectives & Other Characters". The Christie Mystery. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Christie, Agatha (2018). Three Act Tragedy. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0008255787. OCLC 1027804732.

- Hobbs, JD (6 August 1975). "Poirot's Obituary". USA: Poirot. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "About Agatha Christie". Artists. MTV. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "The Monogram Murders". Agatha Christie.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "An interview with Sophie Hannah". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Fane, Vernon (23 March 1946). "The World of Books". The Sphere. p. 3.

- Winn, Dilys (1977). Murder Ink: The Mystery Reader's Companion. New York: Workman Publishing. p. 3.

- Mezei, Kathy. "Spinsters, Surveillance, and Speech: The Case of Miss Marple, Miss Mole, and Miss Jekyll", The Journal of Modern Literature 30.2 (2007): 103–120

- Beehler, Sharon A. "Close vs. Closed Reading: Interpreting the Clues", The English Journal 77.6 (1998): 39–43

- Curran, John (2009). Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks: Fifty Years of Mysteries in the Making. London, UK: Harper-Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-200652-3.

- Gerald, Michael C. (1993). The Poisonous Pen of Agatha Christie. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Curran, John (2011). Agatha Christie: Murder in the Making. London, UK: Harper-Collins. ISBN 9780062065445.

- "John Curran author". www.harpercollins.com. 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- James, P.D. (2009). Talking About Detective Fiction. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-39882-6. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Gillian, Gill (1990). Agatha Christie: The Woman and Her Mysteries. New York: The Free Press.

- Aldiss, Brian. "BBC Radio 4 –Factual –Desert Island Discs". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Osborne, Charles (2001). The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie: A Biographical Companion to the Works of Agatha Christie. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Flood, Alison (2 September 2015). "And Then There Were None declared world's favourite Agatha Christie novel". The Guardian.

- Brown, Jonathan (5 November 2013). "Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd voted best crime novel ever". The Independent. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Symons, Julian (1972). Mortal Consequences: A History from the Detective Story to the Crime Novel. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

- Scott, Sutherland (1953). Blood in Their Ink. Cited in Fitzgibbon (1980). p. 19. London: Stanley Paul.

- Hopkins, Lisa. 2016. Who Owns the Wood? Appropriating A Midsummer Night's Dream. In Shakespearean Allusion in Crime Fiction, ed. L. Hopkins, pp. 63–103. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Pendergast, Bruce (2004), Everyman's Guide to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie, Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford, p. 399, ISBN 1-4120-2304-1

- Brantley, Ben (26 January 2012). "London Theater Journal: Comfortably Mousetrapped". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Moss, Stephen (21 November 2012). "The Mousetrap at 60: Why is this the world's longest-running play?". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- The Mousetrap website Archived 23 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, the-mousetrap.co.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- "The History". The Mousetrap. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Book Review". The New York Times. 17 August 1930. p. 7.

- "Edgars Database – Search the Edgars Database". theedgars.com.

- Riley, Dick; McAllister, Pam; Symons, Julian (2001), "The Bedside, Bathtub & Armchair Companion to Agatha Christie", Continuum, p. 240

- Härcher, Cindy (2011), The Development of Crime Fiction, Grin, p. 7

- Engelhardt, Sandra (2003), The Investigators of Crime in Literature, Tectum, p. 83

- Wilson, Edmund (20 January 1945). "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?". The New Yorker.

- "New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake's 80th birthday". The Guardian. 13 November 2016.

- "Sir Peter Blake's new Beatles' Sgt Pepper's album cover". BBC. 13 November 2016.

- Doyle, Martin (15 September 2015). "Agatha Christie: genius or hack? Crime writers pass judgment and pick favourites". The Irish Times. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Flood, Alison (15 September 2016). "New Agatha Christie stamps deliver hidden clues". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Has Agatha Christie's most enduring mystery been solved?". The Independent. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "About Agatha Christie". Agatha Christie Ltd. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

Her books have sold over a billion copies in the English language and a billion in 44 foreign languages.

- McWhirter, Norris; McWhirter, Ross (1976). Guinness Book of World Records, 11th U.S. Edition. Bantam Books. p. 704.

- Davies, Helen; Dorfman, Marjorie; Fons, Mary; Hawkins, Deborah; Hintz, Martin; Lundgren, Linnea; Priess, David; Robinson, Julia Clark; Seaburn, Paul (14 September 2007). "21 Best-Selling Books of All Time". Editors of Publications International. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- Palmer, Scott (1993). The Films of Agatha Christie. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.

- Debruge, Peter (2 November 2017). "Film Review: 'Murder on the Orient Express'". variety.com. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "BAFTA Awards Database". BAFTA.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Agatha Christie's Criminal Games: Les petits meurtres d'Agatha Christie (original title)". www.imdb.com. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Agatha Christie: 'Queen of Crime' Is a Gentlewoman". Los Angeles Times. 8 March 1970. p. 60, quoted in Gerald (1993), p. 4.