'Ndrangheta

The 'Ndrangheta (/(ən)dræŋˈɡɛtə/,[3] Italian: [nˈdraŋɡeta], Calabrian: [(ɳ)ˈɖɽaɲɟɪta])[lower-alpha 1] is an Italian Mafia-type[4] organized crime syndicate based in the region of Calabria, dating back to the 19th century.

'Ndrangheta's structure | |

| Founding location | Calabria, Italy |

|---|---|

| Years active | since the late 18th century |

| Territory | Italy, Malta, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Netherlands, Albania, United Kingdom, Germany, Slovakia, Romania[1] in Europe Uruguay, Brazil, Colombia, Argentina in South America Canada, Mexico and United States in North America Australia in Oceania |

| Ethnicity | Calabrians |

| Membership (est.) | c. 6,000[2] |

| Criminal activities | pimping, racketeering, drug trafficking, fraud, loan-sharking, weapons trafficking, waste management, money laundering, insurance fraud, corruption, extortion, murder, skimming, political corruption, contract killing, robbery and conspiracy, kidnapping |

| Allies | Camorra Sicilian Mafia Sacra Corona Unita Società foggiana American mafia Albanian mafia Stidda Latin American drug cartels including Los Zetas |

| Rivals | Occasional violent feuds between various 'Ndrangheta clans |

A US diplomat estimated that the organization's narcotics trafficking, extortion and money laundering activities accounted for at least 3% of Italy's GDP in 2010.[5] Since the 1950s, the organization has spread towards Northern Italy and worldwide. According to a 2013 "Threat Assessment on Italian Organised Crime" of Europol and the Guardia di Finanza, the 'Ndrangheta is among the richest (in 2008 their income was around 55 billion dollars) and most powerful organised crime groups in the world.[6]

History

Origin and etymology

The 'Ndrangheta is already known during the reign of the Bourbons of Naples. In the spring of 1792, there was the first official report in history on the 'Ndrangheta, a mission as "Royal Visitor" was entrusted to Giuseppe Maria Galanti; these traveled far and wide throughout most of Calabria, often also making use of reports (answers written on the basis of a sort of questionnaire to fixed questions, prepared by himself) of local notables deemed reliable and trusted. This resulted in a bleak picture, as well as on the economic situation in the region, especially on that of public order.[7] This work has been analyzed by various contemporary historians.[8][7][9][10] Luca Addante defines it well, in the introduction to the re-edition of Galanti's report ("Giornale di viaggio in Calabria", Rubbettino Editore, 2008):[9] "the murders, thefts, the kidnappings were infinite; the ignorance of the clergy was scandalous; the village notables, obsessed with the idea of enriching themselves and then ennobling themselves, rapacious monopolizers of local administrations, who grew up in the shadow of a decadent nobility whose remains were being prepared." Galanti, in particular, reports in the Giornale the descriptions of disturbing crime phenomena, noting how the inefficient administration of justice, the corruption and the monopoly of the barons, was starting to produce cases, as in Maida, of "a small bunch of young, freeloaded young men who commit violence with the use of firearms. Justice is idle because without force and without a system. Malicious people become policemen (a sort of urban guard)." In the District of Gerace, "the raids of the criminals in the countryside are general. Almost all the militiamen are the most troublemakers in the province because the criminals and the debtors adopt this profession and are guaranteed by commanders in contempt of the laws. With this, the crimes, which grow every day".[11]

In 1861, the prefect of Reggio Calabria already noticed the presence of so-called camorristi, a term used at the time since there was no formal name for the phenomenon in Calabria (the Camorra was the older and better known criminal organization in Naples).[12][13] Since the 1880s, there is ample evidence of 'Ndrangheta-type groups in police reports and sentences by local courts. At the time they were often being referred to as the picciotteria, onorata società (honoured society) or camorra and mafia.[14]

These secret societies in the areas of Calabria rich in olives and vines were distinct from the often anarchic forms of banditry and were organized hierarchically with a code of conduct that included omertà – the code of silence – according to a sentence from the court in Reggio Calabria in 1890. An 1897 sentence from the court in Palmi mentioned a written code of rules found in the village of Seminara based on honour, secrecy, violence, solidarity (often based on blood relationships) and mutual assistance.[15]

In the folk culture surrounding 'Ndrangheta in Calabria, references to the Spanish Garduña often appear. Aside from these references, however, there is nothing to substantiate a link between the two organizations. The Calabrian word 'Ndrangheta derives from Greek[16] ἀνδραγαθία andragathía for "heroism" and manly "virtue"[17] or ἀνδράγαθος andrágathos, compound words of ἀνήρ, anḗr (gen. ἀνδρóς, andrós), i.e. man,[18] and ἀγαθός, agathós, i.e. good, brave,[19] meaning a courageous man.[20][21] In many areas of Calabria the verb 'ndranghitiari, from the Greek verb andragathízesthai,[22] means "to engage in a defiant and valiant attitude".[23]

Though in recorded use earlier,[24] the word 'Ndrangheta was brought to a wider audience by the Calabrian writer Corrado Alvaro in the Corriere della Sera in September 1955.[25][26]

Modern history

Until 1975, the 'Ndrangheta restricted their Italian operations to Calabria, mainly involved in extortion and blackmailing. Their involvement in cigarette contraband expanded their scope and contacts with the Sicilian Mafia and the Neapolitan Camorra. With the arrival of large public works in Calabria, skimming of public contracts became an important source of income. Disagreements over how to distribute the spoils led to the First 'Ndrangheta war killing 233 people.[27] The prevailing factions began to kidnap rich people located in northern Italy for ransom. A high-profile target was John Paul Getty III, who was kidnapped for ransom in July 1973, had his severed ear mailed to a newspaper in November, and later released in December following the negotiated payment of $2.2 million by Getty's grandfather, J. Paul Getty.[28]

The Second 'Ndrangheta war raged from 1985 to 1991. The bloody six-year war between the Condello-Imerti-Serraino-Rosmini clans and the De Stefano-Tegano-Libri-Latella clans led to more than 600 deaths.[29][30] The Sicilian Mafia contributed to the end of the conflict and probably suggested the subsequent set up of a superordinate body, called La Provincia, to avoid further infighting. In the 1990s, the organization started to invest in the illegal international drug trade, mainly importing cocaine from Colombia.[31]

Deputy President of the regional parliament of Calabria Francesco Fortugno was killed by the 'Ndrangheta on 16 October 2005 in Locri. Demonstrations against the organization then ensued, with young protesters carrying banderoles reading "Ammazzateci tutti!",[32] Italian for "Kill us all". The national government started a large-scale enforcement operation in Calabria and arrested numerous 'ndranghetisti including the murderers of Fortugno.[33]

The 'Ndrangheta has expanded its activities to Northern Italy, mainly to sell drugs and to invest in legal businesses which could be used for money laundering. In May 2007 twenty members of 'Ndrangheta were arrested in Milan.[33] On 30 August 2007, hundreds of police raided the town of San Luca, the focal point of the bitter San Luca feud between rival clans among the 'Ndrangheta. Over 30 men and women, linked to the killing of six Italian men in Germany, were arrested.[34]

Since 30 March 2010, the 'Ndrangheta has been considered an organisation of mafia-type association according to 416 bis under the Italian penal code.[4]

On 9 October 2012, following a months-long investigation by the central government, the City Council of Reggio Calabria headed by Mayor Demetrio Arena was dissolved for alleged ties to the group. Arena and all the 30 city councilors were sacked to prevent any "mafia contagion" in the local government.[35][36] This was the first time a government of a capital of a provincial government was dismissed. Three central government-appointed administrators will govern the city for 18 months until new elections.[37] The move came after unnamed councilors were suspected of having ties to the 'Ndrangheta under the 10-year centre-right rule of Mayor Giuseppe Scopelliti.[38]

'Ndrangheta infiltration of political offices is not limited to Calabria. On 10 October 2012, the commissioner of Milan's regional government in charge of public housing, Domenico Zambetti of People of Freedom (PDL), was arrested on accusations he paid the 'Ndrangheta in exchange for an election victory and to extort favours and contracts from the housing official, including construction tenders for the World Expo 2015 in Milan.[39] The probe of alleged vote-buying underscores the infiltration of the 'Ndrangheta in the political machine of Italy's affluent northern Lombardy region. Zambetti's arrest marked the biggest case of 'Ndrangheta infiltration so far uncovered in northern Italy and prompted calls for Lombardy governor Roberto Formigoni to resign.[40][41]

In 2014, in the FBI and Italian police joint operation New Bridge, members of both the Gambino and Bonanno families were arrested, as well as ten members of the Ursino clan.[42] Raffaele Valente was among the arrested. In Italian wiretaps, he revealed that he had set up a faction of the Ursino 'Ndrangheta in New York City. Valente was convicted for attempting to sell a sawn-off shotgun and a silencer to an undercover FBI agent for $5000 at a bakery in Brooklyn. He was sentenced to 3 years and one month in prison.[43] Gambino associate Franco Lupoi and his father-in-law, Nicola Antonio Simonetta, were described as the linchpins of the operation. In June 2014, Pope Francis denounced the 'Ndrangheta for their "adoration of evil and contempt of the common good" and vowed that the Church would help tackle organized crime, saying that Mafiosi were excommunicated. A spokesperson for the Vatican clarified that the pope's words did not constitute a formal excommunication under canon law, as a period of legal process is required beforehand.[44]

On 12 December 2017, 48 members of 'Ndrangheta were arrested for mafia association, extortion, criminal damage, fraudulent transferral of assets and illegal possession of firearms. Out of the 48 arrested, four were forced to house arrest and 44 were ordered to jail detention.[45] Two-time mayor of Taurianova, Calabria and his former cabinet member were among the indicted. It was alleged by investigators that the Calabrian clans had infiltrated construction of public works, control of real estate brokerage, food fields, greenhouse production and renewable energy.[46]

On 9 January 2018, law enforcement in Italy and Germany arrested 169 people in connection with the 'Ndrangheta mafia, specifically the Farao and Marincola clans based in Calabria. Assets worth €50 million (£44/$59m) were seized. The indictment mentions that owners of German restaurants, ice cream parlours, hotels and pizzerias were forced to buy wine, pizza dough, pastries and other products made in southern Italy. The Farao clan was being led by life-imprisoned Giuseppe Farao, before the arrests, and was passing orders onto his sons. They controlled bakeries, vineyards, olive groves, funeral homes, launderettes, plastic recycling plants and shipyards.[47] The waste disposal of the Ilva steel company based in Taranto was also infiltrated. Some of the charges were mafia association, attempted murder, money laundering, extortion and illegal weapons possession and trafficking. Italian prosecutor, Nicola Gratteri, said that the arrests were the most important step taken against the 'Ndrangehta within the past 20 years.[48] Eleven suspects were detained and accused of blackmailing and money laundering. They were deported back to Italy.[49] Alessandro Figliomeni, former Mayor of Siderno, Calabria, was sentenced to 12 years in prison on 7 May 2018. He is alleged to be a member of the Commisso 'ndrina clan and served in the top hierarchy.[50]

In December 2019, more than 300 people were arrested in Calabria on suspicion of belonging to the 'Ndrangheta in an operation involving 2,500 police. Among those arrested was Giancarlo Pittelli, a prominent lawyer and former member of Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia party.[51] The arrests were said by Nicola Gratteri, the chief prosecutor in Catanzaro, to be the second largest in number in the history of Italian organised crime, after those that led to the so-called "Maxi Trial" of Sicilian Mafia bosses in Palermo between 1986 and 1992.[51]

Characteristics

Italian anti-organized crime agencies estimated in 2007 that the 'Ndrangheta has an annual revenue of about € 35–40 billion (US$50–60 billion), which amounts to approximately 3.5% of the GDP of Italy.[31][33] This comes mostly from illegal drug trafficking, but also from ostensibly legal businesses such as construction, restaurants and supermarkets.[52] The 'Ndrangheta has a strong grip on the economy and governance in Calabria. According to a US Embassy cable leaked by WikiLeaks, Calabria would be a failed state if it were not part of Italy. The 'Ndrangheta controls huge segments of its territory and economy, and accounts for at least three percent of Italy's GDP through drug trafficking, extortion, skimming of public contracts, and usury. Law enforcement is hampered by a lack of both human and financial resources.[53][54]

The principal difference with the Mafia is in recruitment methods. The 'Ndrangheta recruits members on the criterion of blood relationships resulting in an extraordinary cohesion within the family clan that presents a major obstacle to investigation. Sons of 'ndranghetisti are expected to follow in their fathers' footsteps, and go through a grooming process in their youth to become giovani d'onore (boys of honour) before they eventually enter the ranks as uomini d'onore (men of honour). There are relatively few Calabrian mafiosi who have opted out to become a pentito; at the end of 2002, there were 157 Calabrian witnesses in the state witness protection program.[55] Unlike the Sicilian Mafia in the early 1990s, they have meticulously avoided a head-on confrontation with the Italian state.

Prosecution in Calabria is hindered by the fact that Italian judges and prosecutors who score highly in exams get to choose their posting; those who are forced to work in Calabria will usually request to be transferred right away.[31] With weak government presence and corrupt officials, few civilians are willing to speak out against the organization.

Structure

Organizational structure

Both the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and the 'Ndrangheta are loose confederations of about one hundred organised groups, also called "cosche" or families, each of which claims sovereignty over a territory, usually a town or village, though without ever fully conquering and legitimizing its monopoly of violence.[56]

There are approximately 100 of these families, totaling between 4,000 and 5,000 members in Reggio Calabria.[52][57][58] Other estimates mention 6,000–7,000 men; worldwide there might be some 10,000 members.[31]

Most of the groups (86) operate in the Province of Reggio Calabria, although a portion of the recorded 70 criminal groups based in the Calabrian provinces Catanzaro and Cosenza also appears to be formally affiliated with the 'Ndrangheta.[59] The families are concentrated in poor villages in Calabria such as Platì, Locri, San Luca, Africo and Altomonte as well as the main city and provincial capital Reggio Calabria.[60] San Luca is considered to be the stronghold of the 'Ndrangheta. According to a former 'ndranghetista, "almost all the male inhabitants belong to the 'Ndrangheta, and the Sanctuary of Polsi has long been the meeting place of the affiliates."[61] Bosses from outside Calabria, from as far as Canada and Australia, regularly attend the meetings at the Sanctuary of Polsi.[59]

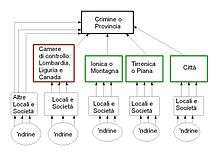

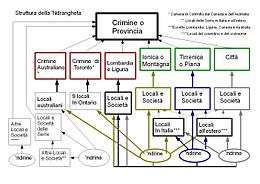

The basic local organizational unit of the 'Ndrangheta is called a locale (local or place) with jurisdiction over an entire town or an area in a large urban center.[62] A locale may have branches, called 'ndrina (plural: 'ndrine), in the districts of the same city, in neighbouring towns and villages, or even outside Calabria, in cities and towns in the industrial North of Italy in and around Turin and Milan: for example, Bardonecchia, an alpine town in the province of Turin in Piedmont, has been, the first municipality in northern Italy dissolved for alleged mafia infiltration, with the arrest of the historical 'Ndrangheta boss of the city, Rocco Lo Presti.[63] The small towns of Corsico and Buccinasco in Lombardy are considered to be strongholds of the 'Ndrangheta. Sometimes sotto 'ndrine are established. These subunits enjoy a high degree of autonomy – they have a leader and independent staff. In some contexts the 'ndrine have become more powerful than the locale on which they formally depend.[61] Other observers maintain that the 'ndrina is the basic organizational unit. Each 'ndrina is "autonomous on its territory and no formal authority stands above the " 'ndrina boss", according to the Antimafia Commission. The 'ndrina is usually in control of a small town or a neighborhood. If more than one 'ndrina operates in the same town, they form a locale.[59]

Blood family and membership of the crime family overlap to a great extent within the 'Ndrangheta. By and large, the 'ndrine consist of men belonging to the same family lineage. Salvatore Boemi, anti-mafia prosecutor in Reggio Calabria, told the Italian Antimafia Commission that "one becomes a member for the simple fact of being born in a mafia family," although other reasons might attract a young man to seek membership, and non-kin have also been admitted. Marriages help cement relations within each 'ndrina and to expand membership. As a result, a few blood families constitute each group, hence "a high number of people with the same last name often end up being prosecuted for membership of a given 'ndrina." Indeed, since there is no limit to the membership of a single unit, bosses try to maximize descendants.[59]

At the bottom of the chain of command are the picciotti d'onore or soldiers, who are expected to perform tasks with blind obedience until they are promoted to the next level of cammorista, where they will be granted command over their own group of soldiers. The next level, separated by the 'ndrina but part of 'Ndrangheta, is known as santista and higher still is the vangelista, upon which the up-and-coming gangster has to swear their dedication to a life of crime on the Bible. The Quintino, also called Padrino, is the second-highest level of command in a 'Ndrangheta clan (name Ndrina), being made up of five privileged members of the crime family who report directly to the boss, the capobastone (head of command).[64]

Power structure

For many years, the power apparatus of the single families were the sole ruling bodies within the two associations, and they have remained the real centers of power even after superordinate bodies were created in the Cosa Nostra beginning in the 1950s (the Sicilian Mafia Commission) and in the 'Ndrangheta a superordinate body was created only in 1991 as the result of negotiations to end years of inter-family violence.[56]

Unlike the Sicilian Mafia, the 'Ndrangheta managed to maintain a horizontal organizational structure up to the early 1990s, avoiding the establishment of a formal superordinate body. Information of several witnesses has undermined the myth of absolute autonomy of Calabrian crime families, however. At least since the end of the 19th century, stable mechanisms for coordination and dispute settlement were created. Contacts and meetings among the bosses of the locali were frequent.[65]

A new investigation, known as Operation Crimine, which ended in July 2010 with an arrest of 305 'Ndrangheta members revealed that the 'ndrangheta was extremely "hierarchical, united and pyramidal," and not just clan-based as previously believed, as said by Italy's chief anti-mafia prosecutor Pietro Grasso.[66]

At least since the 1950s, the chiefs of the 'Ndrangheta locali have met regularly near the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Polsi in the municipality of San Luca during the September Feast. These annual meetings, known as the crimine, have traditionally served as a forum to discuss future strategies and settle disputes among the locali. The assembly exercises weak supervisory powers over the activities of all 'Ndrangheta groups. Strong emphasis was placed on the temporary character of the position of the crimine boss. A new representative was elected at each meeting.[65] Far from being the "boss of bosses," the capo crimine actually has comparatively little authority to interfere in family feuds or to control the level of interfamily violence.[59]

At these meetings, every boss "must give account of all the activities carried out during the year and of all the most important facts taking place in his territory such as kidnappings, homicides, etc."[65] The historical preeminence of the San Luca family is such that every new group or locale must obtain its authorization to operate and every group belonging to the 'Ndrangheta "still has to deposit a small percentage of illicit proceeds to the principale of San Luca in recognition of the latter's primordial supremacy."[67]

Security concerns have led to the creation in the 'Ndrangheta of a secret society within the secret society: La Santa. Membership in the Santa is only known to other members. Contrary to the code, it allowed bosses to establish close connections with state representatives, even to the extent that some were affiliated with the Santa. These connections were often established through the Freemasonry, which the santisti – breaking another rule of the traditional code – were allowed to join.[56][68]

Since the end of the Second 'Ndrangheta war in 1991, the 'Ndrangheta is ruled by a collegial body or Commission, known as La Provincia. Its primary function is the settlement of inter-family disputes.[69][70] The body, also referred to as the Commission in reference to its Sicilian counterpart, is composed of three lower bodies, known as mandamenti. One for the clans on the Ionic side (the Aspromonte mountains and Locride) of Calabria, a second for the Tyrrhenian side (the plains of Gioia Tauro) and one central mandamento for the city of Reggio Calabria.[69]

Activities

According to Italian DIA (Direzione Investigativa Antimafia, Department of the Police of Italy against organized crime) and Guardia di Finanza (Italian Financial Police and Customs Police) the "'Ndrangheta is now one of the most powerful criminal organizations in the world."[71][72] Economic activities of 'Ndrangheta include international cocaine and weapons smuggling, with Italian investigators estimating that 80% of Europe's cocaine passes through the Calabrian port of Gioia Tauro and is controlled by the 'Ndrangheta.[31] However, according to a report of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) and Europol, the Iberian Peninsula is considered the main entry point for cocaine into Europe and a gateway to the European market.[73] The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that in 2007 nearly ten times as much cocaine was intercepted in Spain (almost 38 MT) in comparison with Italy (almost 4 MT).[74]

'Ndrangheta groups and Sicilian Cosa Nostra groups sometimes act as joint ventures in cocaine trafficking enterprises.[75][76] Further activities include skimming money off large public work construction projects, money laundering and traditional crimes such as usury and extortion. 'Ndrangheta invests illegal profits in legal real estate and financial activities.

In early February 2017, the Carabinieri arrested 33 suspects in the Calabrian mafia's Piromalli 'ndrina ('Ndrangheta) which was allegedly exporting fake extra virgin olive oil to the U.S.; the product was actually inexpensive olive pomace oil fraudulently labeled.[77] In early 2016, the American television program 60 Minutes had warned that "the olive oil business has been corrupted by the Mafia" and that "Agromafia" was $16-billion per year enterprise.[78]

The business volume of the 'Ndrangheta is estimated at almost 44 billion euro in 2007, approximately 2.9% of Italy's GDP, according to Eurispes (European Institute of Political, Economic and Social Studies) in Italy. Drug trafficking is the most profitable activity with 62% of the total turnover.[79]

| Illicit activity | Income |

|---|---|

| Drug trafficking | € 27.240 billion |

| Commercial enterprise and public contracts | € 5.733 billion |

| Extortion and usury | € 5.017 billion |

| Arms trafficking | € 2.938 billion |

| Prostitution and human trafficking | € 2.867 billion |

| Total | € 43.795 billion |

Outside Italy

The 'Ndrangheta has had a remarkable ability to establish branches abroad, mainly through migration. The overlap of blood and mafia family seems to have helped the 'Ndrangheta expand beyond its traditional territory: "The familial bond has not only worked as a shield to protect secrets and enhance security, but also helped to maintain identity in the territory of origin and reproduce it in territories where the family has migrated." 'Ndrine are reported to be operating in northern Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, the rest of Europe, the United States, Canada, and Australia.[59] One group of 'ndranghetistas discovered outside Italy was in Ontario, Canada, several decades ago. They were dubbed the Siderno Group by Canadian judges as most of its members hailed from and around Siderno.[80]

Magistrates in Calabria sounded the alarm a few years ago about the international scale of the 'Ndrangheta's operations. It is now believed to have surpassed the traditional axis between the Sicilian and American Cosa Nostra, to become the major importer of cocaine to Europe.[81] Outside Italy 'Ndrangheta operates in several countries, such as:

Albania

According to the German Federal Intelligence Service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), in a leaked report to a Berlin newspaper, states that the 'Ndrangheta "act in close co-operation with Albanian mafia families in moving weapons and narcotics across Europe's porous borders".[82]

Argentina

In November 2006, a cocaine trafficking network that operated in Argentina, Spain and Italy was dismantled. The Argentinian police said the 'Ndrangheta had roots in the country and shipped cocaine through Spain to Milan and Turin.[83]

Australia

Known by the name "The Honoured Society," the 'Ndrangheta controlled Italian-Australian organized crime all along the East Coast of Australia since the early 20th century. 'Ndrangheta operating in Australia include the Sergi, Barbaro and Papalia clans.[84] Similarly in Victoria the major families are named as Italiano, Arena, Muratore, Benvenuto, and Condello. In the 1960s warfare among 'Ndrangheta clans broke out over the control of the Victoria Market in Melbourne, where an estimated $45 million worth of fruits and vegetables passed through each year. After the death of Domenico Italiano, known as Il Papa, different clans tried to gain control over the produce market. At the time it was unclear that most involved were affiliated with the 'Ndrangheta.[85][86]

The 'Ndrangheta began in Australia in Queensland, where they continued their form of rural organized crime, especially in the fruit and vegetable industry. After the 1998–2006 Melbourne gangland killings which included the murder of 'Ndrangheta Godfather Frank Benvenuto. In 2008, the 'Ndrangheta were tied to the importation of 15 million ecstasy pills to Melbourne, at the time the world's largest ecstasy haul. The pills were hidden in a container-load of tomato cans from Calabria. Australian 'Ndrangheta boss Pasquale Barbaro was arrested. Pasquale Barbaro's father Francesco Barbaro was a boss throughout the 1970s and early 1980s until his retirement.[87] Several of the Barbaro clan, including among others, Francesco, were suspected in orchestrating the murder of Australian businessman Donald Mackay in July 1977 for his anti-drugs campaign.[88]

Italian authorities believe that former Western Australian mayor of the city of Stirling, Tony Vallelonga, is an associate of Giuseppe Commisso, boss of the Siderno clan of the Ndrangheta.[89] In 2009, Italian police overheard the two discussing Ndrangheta activities.[89] Since migrating from Italy to Australia in 1963, Vallelonga has "established a long career in grass-roots politics."[90]

The 'Ndrangheta are also tied to large cocaine imports. Up to 500 kilograms of cocaine was documented relating to the mafia and Australian associates smuggled in slabs of marble, plastic tubes and canned tuna, coming from South America to Melbourne via Italy between 2002 and 2004.[91]

Belgium

'Ndrangheta clans purchased almost "an entire neighbourhood" in Brussels with laundered money originating from drug trafficking. On 5 March 2004, 47 people were arrested, accused of drug trafficking and money laundering to purchase real estate in Brussels for some 28 million euros. The activities extended to the Netherlands where large quantities of heroin and cocaine had been purchased by the Pesce-Bellocco clan from Rosarno and the Strangio clan from San Luca.[92][93]

Brazil

Forces of the Brazilian Polícia Federal have linked illegal drug trading activities in Brazil to Ndragueta in operation Monte Pollino,[94] which disassembled cocaine exportation schemes to Europe.

Canada

According to a May 2018 news report, "Siderno's Old World 'Ndrangheta boss sent acolytes to populate the New World" including Michele (Mike) Racco who settled in Toronto in 1952, followed by other mob families. By 2010, investigators in Italy said that Toronto's 'Ndrangheta had climbed "to the top of the criminal world" with "an unbreakable umbilical cord" to Calabria.[95] In the 2018 book, The Good Mothers: The True Story of the Women Who Took on the World's Most Powerful Mafia, Alex Perry reports that the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta has, for the past decade, been replacing the Sicilian Cosa Nostra as the primary drug traffickers in North America.[96]

During a 2018 trial in Toronto, ex-mobster Carmine Guido told the court that the 'Ndrangheta is a collection of family-based clans, each with its own boss, working within a uniform structure and under board of control.[97]

The Canadian 'Ndrangheta is believed to be involved in various activities including the smuggling of unlicensed tobacco products through ties with criminal elements in cross-border Native American tribes.[98] According to Alberto Cisterna of the Italian National Anti-Mafia Directorate, the 'Ndrangheta has a heavy presence in Canada. "There is a massive number of their people in North America, especially in Toronto. And for two reasons. The first is linked to the banking system. Canada's banking system is very secretive; it does not allow investigation. So Canada is the ideal place to launder money. The second reason is to smuggle drugs." The 'Ndrangheta have found Canada a useful North American entry point.[99] The organization used extortion, loan sharking, theft, electoral crimes, mortgage and bank fraud, crimes of violence and cocaine trafficking.[100][101]

A Canadian branch labelled the Siderno Group – because its members primarily came from the Ionian coastal town of Siderno in Calabria – is the one discussed earlier. It has been active in Canada since the 1950s, originally formed by Michele (Mike) Racco who was the head of the Group until his death in 1980. Siderno is also home to one of the 'Ndrangheta's biggest and most important clans, heavily involved in the global cocaine business and money laundering.[99] Antonio Commisso, the alleged leader of the Siderno group, is reported to lead efforts to import "... illicit arms, explosives and drugs ..."[102] Elements of 'Ndrangheta have been reported to have been present in Hamilton, Ontario as early as 1911.[103] Historical crime families in the Hamilton area include the Musitanos, Luppinos and Papalias.[104]

According to an agreed Statement of Fact filed with the court, "the Locali [local cells] outside of Calabria replicate the structure from Calabria, and are connected to their mother-Locali in Calabria. The authority to start Locali outside Calabria comes from the governing bodies of the organization in Calabria. The Locali outside of Calabria are part of the same 'Ndrangheta organization as in Calabria, and maintain close relationships with the Locali where its members come from." The group's activities in the Greater Toronto Area were controlled by a group known as the 'Camera di Controllo' which "makes all of the final decisions", according to the witness' testimony.[100] It consists of six or seven Toronto-area men, who co-ordinate activities and resolves disputes among Calabrian gangsters in Southern Ontario. In 1962, Racco established a crimini or Camera di Controllo in Canada with the help of Giacomo Luppino and Rocco Zito.[105][106][107][108] One of the members was Giuseppe Coluccio, before he was arrested and extradited to Italy.[109] Other members are Vincenzo DeMaria,[110][111] Carmine Verduci before his death,[112] and Cosimo Stalteri before his death.[113] In August 2015, the IRB issued a deportation order for Carmelo Bruzzese.[114] Bruzzese appealed the decision to the Federal Court of Canada, but it was rejected,[114] and on 2 October 2015, Bruzzese was escorted onto a plane in Toronto, landing in Rome, where he was arrested by Italian police.[115] Major Giuseppe De Felice, a commander with the Carabinieri, told the IRB that Bruzzese "assumed the most important roles and decisions. He gave the orders."[115]

After living in Richmond Hill, Ontario for five years until 2010, Antonio Coluccio was one of 29 people named in arrest warrants in Italy in September 2014. Police said they were part of the Commisso 'ndrina ('Ndrangheta) crime family in Siderno. In July 2018, Coluccio was sentenced to 30 years in prison for corruption. His two brothers, including Salvatore and Giuseppe Coluccio, were already in prison due to Mafia-related convictions.[116]

In June 2018, Cosimo Ernesto Commisso, of Woodbridge, Ontario and an unrelated woman were shot and killed. According to sources contacted by the Toronto Star, "Commisso was related to Cosimo "The Quail" Commisso of Siderno, Italy, who has had relations in Ontario, is considered by police to be a "'Ndrangheta organized crime boss".[117] The National Post reported that Cosimo Ernesto Commisso, while not a known criminal, "shares a name and family ties with a man who has for decades been reputed to be a Mafia leader in the Toronto area".[118] The cousin of "The Quail", Antonio Commisso, was on the list of most wanted fugitives in Italy until his capture on 28 June 2005, in Woodbridge.[119]

In June 2015, RCMP led police raids across the Greater Toronto Area, named Project OPhoenix, which resulted in the arrest of 19 men, allegedly affiliated with the 'Ndrangheta. In March 2018, during the resultant criminal trial north of Toronto, the court heard from a Carabinieri lieutenant-colonel that 'Ndrangheta is active in Germany, Australia and the Greater Toronto Area. "People in Italy have to be responsible for their representatives here but the final word comes from Italy".[120] A member of the Greater Toronto Area's 'Ndrangheta cell, Carmine Guido, who had been a police informant, testified at length in 2018 about the structure and activities of the organization which had been under the control of Italian-born Bradford, Ontario resident, Giuseppe (Pino) Ursino and Romanian-born Cosmin (Chris) Dracea of Toronto. The latter two faced two counts of cocaine trafficking for the benefit of a criminal organization and one charge of conspiracy to commit an indictable offence.[121] Guido was paid $2.4 million by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police between 2013 and 2015 to secretly tape dozens of conversations with suspected 'Ndrangheta members.[121][122][123] In February 2019, Ursino was sentenced to 11 and a half years in prison on drug trafficking charges, with Dracea sentenced to nine years in prison on cocaine trafficking conspiracy. Neither had a previous criminal record. At the sentencing, the presiding judge made this comment: "Based on the evidence at trial, Giuseppe Ursino is a high-ranking member of the 'Ndrangheta who orchestrated criminal conduct and then stepped back to lessen his potential implication" ... Cosmin Dracea knew he was dealing with members of a criminal organization when he conspired to import cocaine".[124]

During the Ursino/Dracea trial, an Italian police expert testified that the 'Ndrangheta operated in the Greater Toronto Area and in Thunder Bay particularly in drug trafficking, extortion, loan sharking, theft of public funds, robbery, fraud, electoral crimes and crimes of violence. After the trial, Tom Andreopoulos, deputy chief federal prosecutor, said that this was the first time in Canada that the 'Ndrangheta was targeted as an organized crime group since 1997, when the Criminal Code was amended to include the offence of criminal organization.[125] He offered this comment about the organization:[126]

"We're talking about structured organized crime. We're talking about a political entity, almost; a culture of crime that colonizes across the sea from Italy to Canada. This is one of the most sophisticated criminal organizations in the world."

On 18 July 2019, the York Regional Police announced the largest organized crime bust in Ontario, part of an 18-month long operation called Project Sindicato that was also coordinated with the Italian State Police.[127] York Regional Police had arrested 15 people in Canada, 12 people in Calabria, and seized $35 million worth of homes, sports cars and cash in a major trans-Atlantic probe targeting the most prominent wing of the 'Ndrangheta in Canada headed by Angelo Figliomeni. On 14 and 15 July, approximately 500 officers raided 48 homes and businesses across the GTA, seizing 27 homes worth $24 million, 23 cars, including five Ferraris, and $2 million in cash and jewelry. Nine of the 15 arrests in Canada included major crime figures: Angelo Figliomeni, Vito Sili, Nick Martino, Emilio Zannuti, Erica Quintal, Salvatore Oliveti, Giuseppe Ciurleo, Rafael Lepore and Francesco Vitucci.[128] The charges laid included tax evasion, money laundering, defrauding the government and participating in a criminal organization.[129]

During a press conference in Vaughan, Ontario, Fausto Lamparelli of the Italian State Police, offered this comment about the relationship between the 'Ndrangheta in Ontario and Calabria:[130]

"This investigation allowed us to learn something new. The 'Ndrangheta crime families in Canada are able to operate autonomously, without asking permission or seeking direction from Italy. Traditionally, 'Ndrangheta clans around the world are all subservient to the mother ship in Calabria. It suggests the power and influence the Canadian-based clans have built."

On 9 August 2019, as part of the same joint investigation, several former Greater Toronto Area residents were arrested in Calabria, including Giuseppe DeMaria, Francesco Commisso, Rocco Remo Commisso, Antonio Figliomeni and Cosimo Figiomeni.[131] Vincenzo Muià had visited Toronto on 31 March 2019 to meet with Angelo and Cosimo Figliomeni, seeking answers to who had ambushed and killed his brother, Carmelo Muià, in Siderno on 18 January 2018; Muià's smartphone was unwittingly and secretly transmitting his closed-door conversations to authorities in Italy.[132]

Colombia

The 'Ndrangheta clans were closely associated with the AUC paramilitary groups led Salvatore Mancuso, a son of Italian immigrants; he surrendered to Álvaro Uribe's government to avoid extradition to the U.S.[133] According to Giuseppe Lumia of the Italian Parliamentary Antimafia Commission, 'Ndrangheta clans are actively involved in the production of cocaine.[134]

Germany

According to a study by the German foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), 'Ndrangheta groups are using Germany to invest cash from drugs and weapons smuggling. Profits are invested in hotels, restaurants and houses, especially along the Baltic coast and in the eastern German states of Thuringia and Saxony.[135][136] Investigators believe that the mafia's bases in Germany are used primarily for clandestine financial transactions. In 1999, the state Office of Criminal Investigation in Stuttgart investigated an Italian from San Luca who had allegedly laundered millions through a local bank, the Sparkasse Ulm. The man claimed that he managed a profitable car dealership, and authorities were unable to prove that the business was not the source of his money. The Bundeskriminalamt (BKA) concluded in 2000 that "the activities of this 'Ndrangheta clan represent a multi-regional criminal phenomenon."[137] In 2009, a confidential report by the BKA said some 229 'Ndrangheta families were living in Germany, and were involved in gun-running, money laundering, drug-dealing, and racketeering, as well as legal businesses. Some 900 people were involved in criminal activity, and were also legal owners of hundreds of restaurants, as well as being major players in the property market in the former East. The most represented 'Ndrangheta family originated from the city of San Luca (Italy), with some 200 members in Germany.[138][139] A war between the two 'Ndrangheta clans Pelle-Romeo (Pelle-Vottari) and Strangio-Nirta from San Luca that had started in 1991 and resulted in several deaths spilled into Germany in 2007; six men were shot to death in front of an Italian restaurant in Duisburg on 15 August 2007.[140][141][142] (See San Luca feud.) According to the head of the German federal police service, Joerg Ziercke, "Half of the criminal groups identified in Germany belong to the 'Ndrangheta. It has been the biggest criminal group since the 1980s. Compared to other groups operating in Germany, the Italians have the strongest organization."[143]

Netherlands

Sebastiano Strangio allegedly lived for 10 years in the Netherlands, where he managed his contacts with Colombian cocaine cartels. He was arrested in Amsterdam on 27 October 2005.[144][145][146] The seaports of Rotterdam and Amsterdam are used to import cocaine. The Giorgi, Nirta and Strangio clans from San Luca have a base in the Netherlands and Brussels (Belgium).[147] In March 2012, the head of the Dutch National Crime Squad (Dienst Nationale Recherche, DNR) stated that the DNR will team up with the Tax and Customs Administration and the Fiscal Information and Investigation Service to combat the 'Ndrangheta.[148]

Malta

David Gonzi, a son of former Prime Minister of Malta Lawrence Gonzi, was accused of illegal activities by acting as a trustee shareholder in a gaming company. The company in question was operated by a Calabrian associate of the 'Ndrangheta in Malta. His name appeared several times on an investigation document of over 750 pages that was commissioned by the tribunal of the Reggio Calabria. Gonzi called the document unprofessional. A European arrest warrant was published for Gonzi to appear at the tribunal but this never materialised. Gonzi, however, was completely exonerated from the list of potential suspects in the 'Ndrangheta gaming bust.[149]

After investigation of the presence of the 'Ndrangheta, 21 gaming outlets had their operation license temporarily suspended in Malta due to irregularities in a period of one year.[150][151][152]

In a Notice of the Conclusion of the Investigation dated 30 June 2016, criminal action was commenced in Italy against 113 persons originally mentioned in the investigation.[153]

Mexico

The 'Ndrangheta works in conjunction with a Mexican drug cartel mercenary army known as Los Zetas in the drug trade.[154]

Slovakia

In February 2018, Slovak investigative journalist Ján Kuciak was shot dead at his home together with his fiancée. At the time of the murder, Kuciak was working on a report about the activities of 'Ndrangheta in Slovakia, including its ties to Slovak politicians.[155]

Switzerland

The crime syndicate has a significant presence in Switzerland since the early 1970s but has operated there with little scrutiny due to the inconspicuous life styles of their members, the Swiss legal landscape, and solid foundations in local businesses. In the aftermath of the San Luca feud in 2007 and subsequent arrests in Italy (Operation "Crimine"), it became clear that the group had also infiltrated the economically proliferous regions of Switzerland and Southern Germany. In March 2016, Swiss law enforcement in cooperation with Italian state prosecutors arrested a total of 15 individuals, 13 in the city of Frauenfeld, 2 in the canton of Valais, accusing them of active membership to an organized crime syndicate also known as "Operazione Helvetica".[156] Since 2015, the Swiss federal police has conducted undercover surveillance and recorded the group's meetings in a restaurant establishment in a small village just outside of Frauenfeld. The meetings were taking place in a relatively remote location using the now defunct entity the "Wängi Boccia Club" as its cover. According to the Italian prosecutor Antonio De Bernardo, there are several cells operating within the jurisdiction of the Swiss Federation, estimating the number of operatives per cell to about 40, and a couple of 100 in total. All of the arrested persons are Italian citizens, the two men arrested in the Valais have already been extradited to Italy, and as of August 2016, one individual arrested in Frauenfeld has been approved for extradition to Italy.[157]

United Kingdom

In London, the Aracri and Fazzari clans are thought to be active in money laundering, catering and drug trafficking.[158]

United States

The earliest evidence of 'Ndrangheta activity in the U.S. points to an intimidation scheme run by the syndicate in Pennsylvania mining towns; this scheme was unearthed in 1906.[159] Current 'Ndrangheta activities in America mainly involve drug trafficking, arms smuggling, and money laundering. It is known that the 'Ndrangheta branches in North America have been associating with Italian-American organized crime. The Suraci family from Reggio Calabria has moved some of its operations to the U.S. The family was founded by Giuseppe Suraci who has been in the United States since 1962. His younger cousin, Antonio Rogliano runs the family in Calabria. On Tuesday, 11 February 2014, both F.B.I. and Italian Police intercepted the transatlantic network of U.S. and Italian crime families. The raid targeted the Gambino and Bonanno families in the U.S. while in Italy, it targeted the Ursino 'ndrina from Gioiosa Jonica. The defendants were charged with drug trafficking, money laundering and firearms offenses, based, in part, on their participation in a transnational heroin and cocaine trafficking conspiracy involving the 'Ndrangheta.[160] The operation began in 2012 when investigators detected a plan by members of the Ursino clan of the 'Ndrangheta to smuggle large amounts of drugs. An undercover agent was dispatched to Italy and was successful in infiltrating the clan. An undercover agent was also involved in the handover of 1.3 kg of heroin in New York as part of the infiltration operation.[161]

Uruguay

On 24 June 2019, 'Ndrangheta leader Rocco Morabito, dubbed the "cocaine king of Milan", escaped from Central Prison in Montevideo alongside three other inmates, escaping "through a hole in the roof of the building". Morabito was awaiting extradition to Italy for international drug trafficking, having been arrested at a Montevideo hotel in 2017 after living in Punta del Este under a false name for 13 years.[162]

In popular culture

Beginning in 2000, music producer Francesco Sbano released three CD compilations of Italian mafia folk songs over a five-year period.[163] Collectively known as La musica della mafia, these compilations consist mainly of songs written by 'Ndrangheta musicians, often sung in Calabrian and dealing with themes such as vengeance (Sangu chiama sangu), betrayal (I cunfirenti), justice within the 'Ndrangheta (Nun c'è pirdunu), and the ordeal of prison life (Canto di carcerato).[164]

See also

- List of 'ndrine

- List of most wanted fugitives in Italy

- List of members of the 'Ndrangheta

- Museo della ndrangheta

- Toxic waste dumping by the 'Ndrangheta

- Camorra

- Sicilian Mafia

- Sacra Corona Unita

Notes

- The initial /n/ is silent in Calabrian unless immediately preceded by a vowel.

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "FBI Italian/Mafia". FBI. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "'Ndrangheta" (US) and "'Ndrangheta". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- "Sentenza storica: "La 'ndrangheta esiste". Lo dice la Cassazione e non è una ovvietà" (in Italian). repubblica.it. 18 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "US Saw mafia ridden Calabria as 'failed state'". The Independent. 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Italian Organised Crime: Threat Assessment Archived 22 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Europol, The Hague, June 2013

- Augusto Placanica. "SCRITTI SULLA CALABRIA" (in Italian). librerianeapolis.it. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Augusto Placanica. "Travel Journal in Calabria (1792), followed by reports and memoirs written on the occasion, critical edition, Napoli, SEN 1982" (in Italian). Università degli Studi di Salerno. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Luca Addante. "Giornale di viaggio in Calabria" (in Italian). rubbettinoeditore.it.

- Franca Assante e Domenico Demarco, Napoli, 1969. "Relazione letta al Convegno di Studi su: "Le istituzioni nel Mezzogiorno e l'opera di Francesco Ricciardi", Foggia, 1993" (in Italian). reciproca.it. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Giuseppe Maria Galanti. "GIORNALE DI VIAGGIO IN CALABRIA (1792)" (in Italian). tropeamagazine.it.

- (in Italian) "Relazione annuale sulla 'Ndrangheta" Archived 27 November 2013 at WebCite, Italian Antimafia Commission, February 2008.

- Behan, The Camorra, pp. 9–10

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 36

- Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, pp. 23–28

- Turone, Giuliano (2008). Il delitto di associazione mafiosa. Giuffrè editore. p. 97. ISBN 978-88-14-13917-8.

Il vocabolo deriva infatti dal greco antico ανδραγαθία e significa valore, prodezza, carattere del galantuomo.

Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine - ἀνδραγαθία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ἀνήρ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ἀγαθός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- lemma ανδραγαθία; Babiniotis, Georgios. Dictionary of Modern Greek. Athens: Lexicology Centre.

- Rosen, Ralph M.; Sluiter, Ineke, eds. (2003). Andreia: Studies in manliness and courage in classical antiquity. Brill. p. 55. ISBN 9789004119956.

- ἀνδραγαθίζεσθαι. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, p. 21

- E.g., Keesing's Contemporary Archives Archived 7 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine (1931), Enciclopedia italiana di scienze, lettere ed arti Archived 2 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine (1938), and Notes et études documentaires Archived 5 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine (1949).

- (in Italian) "La 'ndrangheta transnazionale: Dalla picciotteria alla santa – Analisi di un fenomeno criminale globalizzato" Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Giovanni Tizian, March 2009.

- Fabio Truzzolillo, "The 'Ndrangheta: the current state of historical research," Modern Italy (August 2011) 16#3, pp. 363–383.

- Dickie, Mafia Republic: Italy's Criminal Curse, pp. 137–40 Archived 23 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Catching the Kidnappers Archived 13 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Time, 28 January 1974

- "Godfather's arrest fuels fear of bloody conflict" Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Observer, 24 February 2008.

- (in Italian) "Condello, leader pacato e spietato" Archived 2 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 19 February 2008.

- "Move over, Cosa Nostra." Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 8 June 2006.

- (in German) "Im Schattenreich der Krake" Archived 6 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 19 May 2010.

- "Mafiosi move north to take over the shops and cafés of Milan" Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, 5 May 2007.

- "Mafia suspects arrested in Italy" Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 30 August 2007.

- "Italy sacks Reggio Calabria council over 'mafia ties'" Archived 22 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 9 October 2012.

- "Il Viminale scioglie per mafia il comune di Reggio Calabria" Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 9 October 2012.

- "Italy sacks city government over mafia links" Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, 9 October 2012

- "Sprechi e mafia, caos Pdl in Calabria" Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 23 September 2012.

- "Mafia probe claims political victim" Archived 18 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, 14 October 2012.

- "Milan politician accused of mafia vote-buying" Archived 27 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, 10 October 2012.

- "Formigoni's Cabinet Member Arrested for Election Fraud" Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Corriere della Sera, 10 October 2012.

- Laura Smith-Spark and Hada Messia, CNN (11 February 2014). "Gambino, Bonanno family members held in joint US-Italy anti-mafia raid". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "Fashion-conscious mobster gets over 3 years for gunrunning". The New York Post. 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Pullella, Philip (21 June 2014). "Pope lambasts mobsters, says mafiosi 'are excommunicated'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

Those who in their lives follow this path of evil, as mafiosi do, are not in communion with God. They are excommunicated," he said in impromptu comments at a Mass

- "Huge 'Ndrangheta operation, 48 arrests". ANSA. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Blitz against the 'Ndrangheta, 48 arrests and kidnappings for 25 million euros in Reggino". La Stampa Italy. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Over 160 suspects arrested in German-Italian anti-mafia sweep". The Local Italy. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Mafia raids: Police in Italy and Germany make 169 arrests". BBC News. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Eleven mafia suspects arrested in Germany to be deported to Italy". Euro News. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Former Italian Mayor Gets 12 Years for Mafia Association". OCCRP. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- Tondo, Lorenzo (19 December 2019). "Italian politicians and police among 300 held in mafia bust". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- (in French) "Six morts dans un règlement de comptes mafieux en Allemagne". Le Monde. 15 August 2007.

- "Can Calabria Be Saved?". Wikileaks.ch. 2 December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "Italy's Brutal Export: The Mafia Goes Global" Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Time, 9 March 2011.

- "Crisis among the 'Men of Honor' " Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, interview with Letizia Paoli, Max Planck Research, February 2004.

- "Review of: Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods". Organized-crime.de. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 32.

- (in Italian) "Relazione annuale" Archived 27 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Commissione parliamentare d'inchiesta sul fenomeno della criminalità organizzata mafiosa o similare, 30 July 2003.

- Varese, Federico. "How Mafias Migrate: The Case of the 'Ndrangheta in Northern Italy." Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Law & Society Review. June 2006.

- (in Italian) "La pax della 'ndrangheta soffoca Reggio Calabria" Archived 11 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. La Repubblica. 25 April 2007.

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 29

- Nicaso & Danesi, Made Men, p. 23 Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Bardonecchia comune chiuso per mafia Archived 4 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine La Stampa 29 aprile 1995

- La Sorte, Mike (December 2004). "The 'Ndrangheta Looms Large". americanmafia.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Paoli. Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 59

- "'Ndrangheta mafia structure revealed as Italian police nab 300 alleged mobsters" Archived 19 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, The Associated Press, csmonitor.com, 13 July 2010.

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 29-30

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 116

- Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, pp. 61–62

- (in Italian) Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di Sangue, pp. 65–68

- Ulrich, Andreas (4 January 2012). "Encounters with the Calabrian Mafia: Inside the World of the 'Ndrangheta – SPIEGEL ONLINE". Spiegel Online. Spiegel.de. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Italian mafia 'Ndrangheta, ndrangheta, calabria, John Paul Getty III, Gioia Tauro, columbian drug trafficking, cocaine smuggling italy, vendetta of San Luca, Strangio-Nirta, Pelle-Vottari-Romeo, Maria Strangio, Giovanni Strangio, Duisberg killings". Understandingitaly.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Cocaine: a European Union perspective in the global context Archived 8 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), EMCDDA/ Europol, Lisbon, April 2010.

- World Drug Report 2009 Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, UNODC, 2009

- The Rothschilds of the Mafia on Aruba Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, by Tom Blickman, Transnational Organized Crime, Vol. 3, No. 2, Summer 1997

- (in Italian) "Uno degli affari di Cosa Nostra e 'Ndrangheta insieme" Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Notiziario Droghe, 30 May 2005.

- "Italy Arrests 33 Accused of Olive Oil Fraud". Olive Oil Times. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Don't fall victim to olive oil fraud". www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- (in Italian) "Il fatturato della 'Ndrangheta Holding: 2,9% del Pil nel 2007" Archived 21 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 'Ndrangheta Holding Dossier 2008, Centro Documentazione Eurispes.

- Humphries, Adrian (14 February 2011). "Calabrian Mafia boss earned mob's respect". National Post. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Close family ties and bitter blood feuds Archived 24 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 16 August 2007

- Hall, Allan; Popham, Peter (16 August 2007). "Mafia war blamed for shooting of six Italian men in Germany". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010.

- (in Spanish) Mafia calabresa: cae una red que traficaba droga desde Argentina Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Clarín, 8 November 2006.

- McKenna, Jo (15 March 2010). "Mafia deeply entrenched in Australia". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Omerta in the Antipodes, Time Magazine, 31 January 1964

- L'ascesa della 'Ndrangheta in Australia Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, by Pierluigi Spagnolo, Altreitalie, January–June 2010

- AFP lands 'world's biggest drug haul' Archived 8 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, news.com.au, 8 August 2008

- Bob Bottom (1988). Shadow of Shame: How the mafia got away with the murder of Donald Mackay. Victoria, Australia: Sun Books.

- Sean Cowan (10 March 2011). "Vallelonga 'met senior mafia man'". The West Australian Archived 5 January 2013 at Archive.today

- Nicole Cox et al. "Shocked former Stirling mayor Tony Vallelonga denies mafia connection". News.com.au (9 March 2011). Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Four face trial over Mafia-run drug ring Archived 18 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 January 2010

- (in Italian) "A Bruxelles un intero quartiere comprato dalla 'ndrangheta." Archived 15 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine La Repubblica. 5 March 2004.

- (in French) La mafia calabraise recycle à Bruxelles Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, La Libre Belgique, 6 March 2004.

- "Máfia italiana atua com traficantes – Nacional – Diário do Nordeste". Diário do Nordeste. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "WHEN COPS CAN'T CONVICT A 'TOP MAFIA BOSS,' THEY TURN TO DESPERATE MEASURES". nationalpost.com. 1 May 2018.

- "Canada is on the frontline of a new war against the rise of global organized crime". theglobeandmail.com. 29 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- News; Toronto (29 March 2018). "Ex-mobster paid $2.4M to become police informant tells trial he made far more money as a crook – National Post".

- Thompson, John C. (January 1994). "Sin-Tax Failure: The Market in Contraband Tobacco and Public Safety". The Mackenzie Institute. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- Humphries, Adrian (24 September 2010). "A New Mafia: Crime families ruling Toronto, Italy alleges". National Post. Toronto, Ontario. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Toronto court hears testimony on inner workings of 'Ndrangheta organized crime group". Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener, Ontario. 24 March 2018.

- Peter Edwards (10 April 2018). "Ex-mobster tells court $2.4M he was paid for working as police agent 'isn't half of what I gave up'". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Organized Crime in Canada: A Quarterly Summary". Nathanson Society. June 2005. Archived from the original on 30 March 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- Nicaso, Antonio (24 June 2001). "The twisted code of silence: Part 4 – Murder, extortion and drug dealing exemplified organized crime in Toronto". Corriere Canadese. Viewed 7 April 2007.

- "Unease as mobsters set free". National Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Schneider, Stephen (15 October 1998). Canadian Organized Crime. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press Inc. p. 178. ISBN 1773380249.

- "The life and death of Rocco Zito". torontosun.com. 30 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- "You'd never guess he was a Mafia chieftain': Longtime mob boss killed in violent attack in Toronto home". nationalpost.com. 30 January 2016. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Schneider, Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada, pp. 310

- Life of luxury on hold, National Post, 16 August 2008

- Reputed Mafia boss wants police allegations barred from hearing, National Post, 16 September 2009

- Police lose track of alleged soldier in the mob, until Canadian Tire tussle, National Post, 17 February 2011

- "Court hears details of mob killings in secret recordings". The Star. 27 March 2018. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Calabrian Mafia boss earned mob's respect Archived 4 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The National Post, 14 February 2011

- "Toronto-area grandfather accused of being Italian mob boss ordered deported to face trial". nationalpost.com. 10 August 2015.

- "Suspected Mafia boss deported in renewed push from Canada and Italy against the mob". nationalpost.com. 3 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Adrian Humphreys (18 July 2018). "Heavy prison sentence in Italy against mobster likely ends his yearning to return to Canada". National Post.

- "Man killed in Woodbridge shooting had family ties to organized crime – The Star". Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "'The less you know the better it is': Mob links in murder of man, woman on quiet Woodbridge street". 29 June 2018.

- Back to the 'wolves' Archived 23 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, National Post 30 July 2005

- "Toronto court hears testimony on inner workings of 'Ndrangheta organized crime group". The Star. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "'I was starting to lose my mind,' former mobster tells cocaine trafficking trial". The Star. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Crown calling for lengthy prison sentences in GTA Mafia drug-importing trial Archived 11 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Toronto Star, 9 January 2019

- No excuses 'besides being stupid,' drug smuggler in landmark Mafia trial tells judge at sentencing hearing, The National Post, 9 January 2019

- "Judge sentences 'Ndrangheta crime boss to 11-1/2 years for cocaine conspiracy". Simcoe News. 1 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Toronto judge sentences 'Ndrangheta crime boss to 11 1⁄2 years for cocaine conspiracy". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Membership in Mafia 'better than gold,' landmark trial of two mobsters hears". stratfordbeaconherald.com. 8 November 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Largest mafia bust in Ontario history: 15 arrests, $35 million worth of homes seized". toronto.ctvnews.ca. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "CHARGES LIST- ORGANIZED CRIME CHARGES LAID AND PROCEEDS OF CRIME SEIZED". yrp.ca. 18 July 2019.

- "Project Sindacato ends in arrests of 9 members of alleged crime family in Vaughan". cbc.ca. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Following dirty money leads police to alleged Mafia clan north of Toronto living life of luxury". National Post. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

Also charged are Emilio Zannuti, 48, of Vaughan, alleged to play a senior role in the organization; Vito Sili, 37, of Vaughan, alleged to help move the group's money; Erica Quintal, 30, of Bolton, alleged to be a bookkeeper with the group; Nicola Martino, 52, of Vaughan, alleged to be another money man; Giuseppe Ciurleo, 30, of Toronto, alleged to help Zanutti run gambling; Rafael Lepore, 59, of Vaughan, alleged to be a gambling machine operator; and Francesco Vitucci, 44, of Vaughan, alleged to be Figlimoeni's former driver who moved up to help run a café.

- "Several GTA residents arrested in Italy following Mafia sweep". The Star. 9 August 2019. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "Italian Mafia boss visiting Canada unwittingly carried a police wiretap to his meetings". nationalpost.com. 11 August 2019.

- (in Spanish) "Tiene Italia indicios sobre presencia de cárteles mexicanos en Europa" Archived 24 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, El Universal, 15 April 2007.

- (in Spanish) "La mafia calabresa produce su cocaína en Colombia" Archived 9 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, El Universal (Caracas), 30 October 2007.

- "Italian Mafia Invests Millions in Germany" Archived 28 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Welle, 13 November 2006.

- (in German) "Mafia setzt sich in Deutschland fest" Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine ("Mafia sets firmly in Germany"), Berliner Zeitung, 11 November 2006.

- "A Mafia Wake-Up Call" Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Der Spiegel, 20 August 2007.

- "Report: Germany losing battle against Calabrian mafia" Archived 5 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Earth Times, 12 August 2009.

- (in German) "Italienische Mafia wird in Deutschland heimisch" Archived 14 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine ("Italian Mafia makes home in Germany"), Die Zeit, 12 August 2009.

- "A mafia family feud spills over" Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News Online, 16 August 2007.

- "How the tentacles of the Calabrian Mafia spread from Italy" Archived 6 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Times Online, 15 August 2007.

- "Six Italians Killed in Duisburg" Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Spiegel Online, 15 August 2007.

- "One in two crime gangs in Germany are Italian, police boss says" Archived 3 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Business Ghana, 8 January 2013.

- (in Italian) "'Ndrangheta, preso ad Amsterdam il boss Sebastiano Strangio" Archived 15 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 28 October 2005.

- (in Italian) "'Ndrangheta, estradato dall'Olanda il boss Sebastiano Strangio" Archived 20 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 27 March 2006.

- (in Dutch) "Maffiakillers Duisburg zijn hier" Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, De Telegraaf, 19 August 2007.

- (in Italian) "Olanda, Paese-rifugio dei killer", Il Sole 24 Ore, 18 August 2007.

- (in Dutch) "Recherche onderzoekt 'Ndrangheta" Archived 11 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, NOS, 10 March 2012.

- "Lawyer, consultant exonerated from list of potential suspects in 'Ndrangheta gaming bust". The Malta Independent. 8 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Sansone, Kurt (29 July 2015), "Updated: David Gonzi being investigated in Mafia betting probe. Insists role was limited to providing fiduciary services" Archived 23 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Malta.

- Balzan, Jurden (2 August 2015), "David Gonzi brushes off European arrest warrant threat" Archived 24 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Malta Today,

- Orland, Kevin Schembri (10 October 2015), "'Ndrangheta links to companies: Malta Gaming Authority 'effective regulator' – Jose Herrera" Archived 22 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Malta Independent.

- "'Ndrangheta e gioco online: chiuse indagini per 113 (NOMI)". Il Dispaccio. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- (in Spanish) "Los Zetas toman el control por la 'Forza': Nicola Gratteri" Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Excelsior, 12 October 2008.

- a.s., Petit Press (27 February 2018). "Kuciak investigated links between politicians and mafia". Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "Die 'Ndrangheta kann sich in der Schweiz nicht mehr sicher fühlen" Archived 6 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine-Interview with A. De Bernardo- (in German). Tages Anzeiger online. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "Schweiz liefert ersten Frauenfelder Mafioso aus" Archived 6 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in German). Tages Anzeiger online. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "'Unstoppable' spread of Calabria's 'ndrangheta mafia sees outposts established in UK and Ireland". The Independent. 22 June 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "Who are the 'Ndrangheta", Reuters, 15 August 2007.

- Laura Smith-Spark and Hada Messia, CNN (11 February 2014). "Gambino, Bonanno family members held in joint US-Italy anti-mafia raid". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "Anti-mafia raids in U.S. and Italy". Toronto Sun. 11 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- "Rocco Morabito: Italian mafia boss escapes prison in Uruguay". independent.co.uk. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Songs of the Criminal Life", NPR, 2 October 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2009. Archived 10 September 2009.

- Gerd Ribbeck. "La musica della Mafia" [The music of the Mafia]. Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- Behan, Tom (1996). The Camorra, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09987-0

- Dickie, John (2013). Mafia Republic: Italy's Criminal Curse. Cosa Nostra, 'Ndrangheta and Camorra from 1946 to the Present, London: Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 978-1444726435

- (in Italian) Gratteri, Nicola & Antonio Nicaso (2006). Fratelli di sangue, Cosenza: Pellegrini Editore, ISBN 88-8101-373-8

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style, New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515724-9 (Review by Klaus Von Lampe) (Review by Alexandra V. Orlova)

- Truzzolillo, Fabio. "The 'Ndrangheta: the current state of historical research," Modern Italy (August 2011) 16#3 pp. 363–383.

- Varese, Federico. "How Mafias Migrate: The Case of the 'Ndrangheta in Northern Italy." Law & Society Review, June 2006.

- Nicaso, Antonio; Lamothe, Lee (1995). The Global Mafia: The New World Order of Organized Crime. Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 0-7715-7311-1. Archived from the original on 6 December 2000. Retrieved 21 May 2017.