Yurok

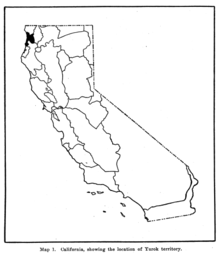

The Yurok (from Yuh'ára, or Yurúkvaarar in the neighboring Karuk language)[3] or as they call themselves Pueleekla’ and Puliklah (from pulik 'downstream' + -la 'people of') both means "downriver people" are Native Americans who live in northwestern California near the Klamath River and Pacific coast.[2] They live on the Yurok Indian Reservation and the surrounding communities in Humboldt, Del Norte and Trinity counties in Northern California.

.jpg) Yurok man and canoe on the Trinity River (California) by Edward S. Curtis, c. 1923 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6,567 alone and in combination[1] (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Yurok[2] | |

| Religion | |

| traditional tribal religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Wiyot[2] |

History

Traditionally, the Yurok lived in permanent villages along the Klamath River. Some of the villages date back to the 14th century.[4] They fished for salmon along rivers, gathered ocean fish and shellfish, hunted game, and gathered plants.[2] Yurok ate varied berries and meats, but whale meat was prized above others. Yuroks did not hunt whales, instead, they waited until a drift whale washed up onto the beach or place near the water and dried the flesh. Salmon is another vital source of food. The major currency of the Yurok nations was the dentalium shell. Alfred L. Kroeber wrote of the Yurok perception of the shell: "Since the direction of these sources is 'downstream' to them, they speak in their traditions of the shells living at the downstream and upstream ends of the world, where strange but enviable peoples live who suck the flesh of univalves."[5]

The Yurok's first contact with non-Natives occurred when Spanish explorers entered their territory in 1775. Fur traders and trappers from the Hudson's Bay Company came in 1827.[4] Following encounters with white settlers moving into their aboriginal lands during a gold rush in 1850, the Yurok were faced with disease and massacres that reduced their population by 75%. In 1855, following the Klamath and Salmon River War, the Lower Klamath River Indian Reservation was created by executive order. The Reservation boundaries included a portion of the Yurok's aboriginal territory and most of the Yurok villages. As a result, the Yurok people were not forcibly removed from their traditional homelands.

Villages

Yurok Villages were composed of individual families that lived in separate, single-family homes.[6] The house was owned by the eldest male and in each lived several generations of men related on their father's side of the family as well as their wives, children, daughters’ husbands, unmarried relatives, and adopted kin.[7] Yurok villages also consisted of sweat houses and menstrual huts. Sweat houses were designated for men of an extended patrilineal family as a place to gather.[6] While during their menstruation cycles, women stayed in separate under-ground huts for ten days.[7] Additionally, inheritance of land was predominantly patrilineal. The majority of the estate was passed down to the fathers’ sons. Daughters and male relatives were also expected to acquire a portion of the estate.[8]

Social Organization

Yurok society was socially stratified, so that communities were divided between the aristocrats, commoners, and slaves.[7][8] The aristocrats were the only group allowed to perform religious duties. Furthermore, they had homes at higher elevations, wore nicer clothing, and spoke in a distinctive manner. The primary reason men became slaves was because they owed money to certain families. Nonetheless, slavery was not considered to be a significant institution.[7][8] Overall, the higher a man's social ranking was, the more valuable his life was considered.[6]

Marriage

When daughters got married, Yurok families would receive a payment from her husband. For the most part, girls were highly valued in the family.[7] The amount of money paid by a man determined the social status of the couple. A wealthy man, who could afford to pay a large sum, increased the couple and their children's rank within the community.[8] When married, both spouses held onto their personal properties but the bride lived with the groom's family and took his last name. Men who were unable to pay the full sum of money could pay half the cost for the bride. In doing so, the couple was considered “half-married.” Half-married couples lived with the bride's family and the groom would then become a slave for them. Furthermore, their children would take on the mother's last name.[7] In cases of divorce, either spouse could initiate their split. The most frequent reason for divorce was if the wife was infertile. If the woman wanted a divorce and to take the children with her, her family had to refund the husband for his initial payment.[8]

Demographics

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber put the 1770 population of the Yurok at 2500.[9] Sherburne F. Cook initially agreed,[10] but later raised this estimate to 3100.[11]

By 1870, the Yurok population had declined to 1350.[12] By 1910 it was reported as 668 or 700.[13]

The United States Census for the year 2000 indicates that there were 4413 Yurok living in California, combining those of one tribal descent and those with ancestors of several different tribes and groups. There were 5,793 Yurok living throughout the United States. The Yurok Indian Reservation is California's largest tribe, with 6357 members as of 2019.[14]

On November 24, 1993, the Yurok Tribe adopted a constitution that details the jurisdiction and territory of their lands. Under the Hoopa-Yurok Settlement Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100-580, qualified applicants had the option of enrolling in the Yurok Tribe. Of the 3,685 qualified applicants for the Settlement Roll, 2,955 people chose Yurok membership. 227 of those members had a mailing address on the Yurok reservation, but a majority lived within 50 miles of the reservation. The Yurok Tribe is currently the largest group of Native Americans in the state of California, with 6357 enrolled members living in or around the reservation.[15] The Yurok reservation of 63,035 acres (25,509 ha) has an 80% poverty rate and 70% of the inhabitants do not have telephone service or electricity, according to the tribe's Web page.

Language

Yurok is one of two Algic languages spoken in California, the other being Wiyot.[2] Between twenty and one hundred people speak the Yurok language today.[16] The language is passed on through master-apprentice teams and through singing.[17] Language classes have been offered through Humboldt State University and through annual language immersion camps.[18]

An unusual feature of the language is that certain nouns change depending upon whether there is one, two, or three of the object. For instance, one human being would be ko:ra' or ko'r, two human beings would be ni'iyel, and three human beings would be nahkseyt.[19]

Contemporary

Fishing, hunting, and gathering remain important to tribal members. Basket weaving and woodcarving are important arts. A traditional hamlet of wooden plank buildings, called Sumeg, was built in 1990. The Jump Dance and Brush Dance are part of tribal ceremonies.[20]

The tribe owns and operates a casino, river jet boat tours and other tourist attractions.[21]

Repatriation efforts

In 2010, 217 sacred artifacts were returned to the Yurok tribe by the Smithsonian Institution.[22][23][24] The condor feathers, headdresses and deerskins had been part of the Smithonian's collection for almost 100 years and represent one of the largest Native American repatriations.[22][23][24] The regalia will be used in Yurok ceremonies and on display at the tribe's cultural center.

Notable people

- Rick Bartow (1946–2016), painter, printmaker, and sculptor

- Archie Thompson (1919–2013), elder who helped revitalize the Yurok language[14][25]

- Lucy Thompson (1856–1932), first indigenous Californian woman to be published

See also

Notes

- "2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010" (PDF). census.gov.

- "California Indians and Their Reservations: Y." San Diego State University Library and Information Access. 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Bright, William; Susan Gehr. "Karuk Dictionary and Texts". Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Pritzker 159

- Kroeber, Alfred L.. [catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002494436 Handbook of the Indians of California.] Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1925, pp. 22-23.

- "Britannica Academic". academic.eb.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- "Gale - Product Login". galeapps.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- "eHRAF World Cultures". ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- Kroeber 1925:883

- Cook 1976:165

- Cook 1956:84

- Cook 1976:237

- Cook 1976:237; Kroeber 1925:883

- Romney, Lee (2013-04-07). "Archie Thompson dies at 93; Yurok elder kept tribal tongue alive". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- Fimrite, Peter (2018-10-01). "Yurok tribe revives ancestral lands by restoring salmon runs, protecting wildlife". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, CA. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- Hinton 32

- Hinton 33

- "Yurok Language Project." University of California, Berkeley, Department of Linguistics. 2011 (retrieved 1 Feb 2011)

- Hinton 120

- Pritzker 161

- Sabalow, Ryan; Kasler, Dale (May 6, 2020). "Why California native tribes are cautious about ending shutdown. 'We can't lose a single elder'". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "Sacred artifacts returned to Northern Calif. tribe". Seattle Times. 14 August 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Yurok Tribe Celebrates Reclaiming Sacred Artifacts". National Public Radio. npr.org. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Back home where they belong: Yurok Tribe celebrates return of dance regalia from museum - Times-Standard". Times-Standard. times-standard.com. 14 August 2010. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Spencer, Adam (2013-04-03). "Elder leaves legacy of language, love". Del Norte Triplicate. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

References

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1956. "The Aboriginal Population of the North Coast of California". Anthropological Records 16:81-130. University of California, Berkeley.

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1976. Yurok Myths. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hinton, Leanne. Flutes of Fire: Essays on California Indian Languages. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 1994. ISBN 0-930588-62-2.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yurok people. |