Young Frankenstein

Young Frankenstein is a 1974 American comedy horror film directed by Mel Brooks and starring Gene Wilder as the title character, a descendant of the infamous Dr. Victor Frankenstein, and Peter Boyle as the monster. The supporting cast includes Teri Garr, Cloris Leachman, Marty Feldman, Madeline Kahn, Kenneth Mars, Richard Haydn, and Gene Hackman. The screenplay was written by Wilder and Brooks.[4]

| Young Frankenstein | |

|---|---|

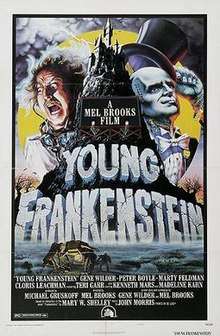

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Mel Brooks |

| Produced by | Michael Gruskoff |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Frankenstein by Mary Shelley |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Morris |

| Cinematography | Gerald Hirschfeld |

| Edited by | John C. Howard |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.78 million[2] |

| Box office | $86.2 million[3] |

The film is a parody of the classic horror film genre, in particular the various film adaptations of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus produced by Universal Pictures in the 1930s.[5] Much of the lab equipment used as props was created by Kenneth Strickfaden for the 1931 film Frankenstein.[6] To help evoke the atmosphere of the earlier films, Brooks shot the picture entirely in black and white, a rarity in the 1970s, and employed 1930s' style opening credits and scene transitions such as iris outs, wipes, and fades to black. The film also features a period score by Brooks' longtime composer John Morris.

A critical favorite and box-office smash, Young Frankenstein ranks No. 28 on Total Film magazine's readers' "List of the 50 Greatest Comedy Films of All Time",[7] No. 56 on Bravo TV's list of the "100 Funniest Movies",[8] and No. 13 on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 funniest American movies.[9] In 2003, it was deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" by the United States National Film Preservation Board, and selected for preservation in the Library of Congress National Film Registry.[10][11] It was later adapted by Brooks and Thomas Meehan as a stage musical.

On its 40th anniversary, Brooks considered it by far his finest (although not his funniest) film as a writer-director.[12]

Plot

Dr. Frederick Frankenstein is a lecturing physician at an American medical school and engaged to Elizabeth, a socialite. He becomes exasperated when anyone brings up the subject of his grandfather Victor Frankenstein, the infamous mad scientist, and insists that his surname is pronounced "Fronkensteen".[13] When a solicitor informs him that he has inherited his family's estate in Transylvania after the death of his great-grandfather, the Baron Beaufort von Frankenstein, Frederick travels to Europe to inspect the property. At the Transylvania train station, he is met by a hunchbacked, bug-eyed servant named Igor, and a young assistant, Inga. Upon hearing that the professor pronounces his name "Fronkensteen", Igor insists that his name is pronounced "Eyegor", rather than the traditional "Eegor".

Upon arrival at the estate, Frederick meets Frau Blucher, the housekeeper. After discovering the secret entrance to his grandfather's laboratory and reading his private journals, Frederick decides to resume his grandfather's experiments in re-animating the dead. He and Igor steal the corpse of a recently executed criminal, and Frederick sets to work experimenting on the large corpse. Igor is sent to steal the brain of a deceased revered historian, Hans Delbrück; startled by his own reflection, he drops and ruins Delbrück's brain. Taking a second brain labeled "Abnormal", Igor returns with it, and Frederick unknowingly transplants it into the corpse.

Soon, Frederick is ready to re-animate his creature, who is eventually brought to life by electrical charges during a lightning storm. The creature takes its first steps, but, frightened by the sight of Igor lighting a match, he attacks Frederick and nearly strangles him before he is sedated. Meanwhile, unaware of the creature's existence, the townspeople gather to discuss their unease at Frederick continuing his grandfather's work. Inspector Kemp, a one-eyed police official with a prosthetic arm, whose German accent is so thick that even his own countrymen cannot understand him,[14] proposes to visit the doctor, whereupon he demands assurance that Frankenstein will not create another monster. On returning to the lab, Frederick discovers Blucher setting the creature free. She reveals the monster's love of violin music and her own romantic relationship with Frederick's grandfather. However, the creature is enraged by sparks from a thrown switch and escapes the castle.

While roaming the countryside, the monster has encounters with a young girl and a blind hermit, references to 1931's Frankenstein.[15] Frederick recaptures the monster and locks the two of them in a room, where he calms the monster's homicidal tendencies with flattery and fully acknowledges his own heritage, shouting out, "My name is Frankenstein!" At a theater full of illustrious guests, Frederick shows "The Creature", dressed in top hat and tails, following simple commands. The demonstration continues with Frederick and the monster performing the musical number "Puttin' On the Ritz". However, the routine ends suddenly when a stage light explodes and frightens the monster, who becomes enraged and charges into the audience, where he is captured and chained by police. Back in the laboratory, Inga attempts to comfort Frederick and they wind up sleeping together on the suspended reanimation table.

The monster escapes when Frederick's fiancée Elizabeth arrives unexpectedly for a visit, taking her captive as he flees. Elizabeth falls in love with the creature due to his "enormous schwanzstucker".[16] The townspeople hunt for the monster; to get the creature back, Frederick plays the violin to lure his creation back to the castle and recaptures him. Just as the Kemp-led mob storms the laboratory, Frankenstein transfers some of his stabilizing intellect to the creature who, as a result, is able to reason with and placate the mob. Elizabeth—with her hair styled after that of the female creature from the Bride of Frankenstein—marries the now erudite and sophisticated monster, while Inga, in bed with Frederick, asks what her new husband got in return during the transfer procedure. Frederick growls wordlessly and embraces Inga who, as Elizabeth did when abducted by the monster, sings the refrain "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life".[17]

Cast

- Gene Wilder as Dr. Frederick Frankenstein

- Peter Boyle as The Monster

- Marty Feldman as Igor

- Cloris Leachman as Frau Blücher

- Teri Garr as Inga

- Kenneth Mars as Inspector Kemp

- Madeline Kahn as Elizabeth

- Richard Haydn as Herr Gerhardt Falkstein (lawyer)

- Richard Roth as Insp. Kemp's Aide

- Monte Landis and Rusty Blitz as Gravediggers

- Gene Hackman as Harold, the blind man

- Mel Brooks as Werewolf / Cat Hit by Dart / Victor Frankenstein (voice)[18][19]

- Listed on screen in opening credits under "with"

- Liam Dunn as Mr. Hilltop

- Danny Goldman as Medical student

- Oscar Beregi as Sadistic Jailor

- Arthur Malet as Village Elder

- Anne Beesley as Helga

- John Madison

- John Dennis

- Rick Norman

- Rolfe Sedan as Train conductor

- Terrance Pushman

- Randolph Dobbs

- Norbert Schiller

- Patrick O'Hara

- Michael Fox

- Lidia Kristen

- Clement von Franckenstein as Villager screaming at the Monster

- Leon Askin as Herr Walman (deleted scenes)

Production

Origins

After several box office failures (including what are now such cult classics as The Producers and Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory), Gene Wilder finally hit box office success with a pivotal role in the 1972 Woody Allen film Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask). It was around that time that Wilder began toying around with an idea for an original story involving the grandson of Victor Frankenstein inheriting his grandfather's mansion and his research.

Wilder had dabbled in screenwriting earlier in his career, writing a few unmade screenplays that were, by his own admission, not very good (the story idea of one of those early screenplays would form the basis of his 2007 novel My French Whore). While writing his story, he was approached by his agent (and future film mogul) Mike Medavoy who suggested he make a film with Medavoy's two new clients, actor Peter Boyle and comedian Marty Feldman. Wilder mentioned his Frankenstein idea, and within a few days, sent Medavoy four pages of his idea (the entire Transylvania train station scene, which he had started writing after seeing Feldman on Dean Martin's Comedy World).

It was Medavoy who suggested that Wilder talk to Mel Brooks about directing. Wilder had already talked to Brooks about the idea early on. After he wrote the two-page scenario, he called Brooks, who told him that it seemed like a "cute" idea but showed little interest.[20] Though Wilder believed that Brooks would not direct a film that he did not conceive, he again approached Brooks a few months later, when the two of them were shooting Blazing Saddles.

In a 2010 interview with Los Angeles Times, Mel Brooks discussed how the film came about:[21]

I was in the middle of shooting the last few weeks of Blazing Saddles somewhere in the Antelope Valley, and Gene Wilder and I were having a cup of coffee and he said, I have this idea that there could be another Frankenstein. I said, "Not another! We've had the son of, the cousin of, the brother-in-law. We don't need another Frankenstein." His idea was very simple: What if the grandson of Dr. Frankenstein wanted nothing to do with the family whatsoever. He was ashamed of those wackos. I said, "That's funny."

In a 2016 interview with Creative Screenwriting, Brooks elaborated on the writing process. He recalled,

Little by little, every night, Gene and I met at his bungalow at the Bel Air Hotel. We ordered a pot of Earl Grey tea coupled with a container of cream and a small kettle of brown sugar cubes. To go with it we had a pack of British digestive biscuits. And step-by-step, ever so cautiously, we proceeded on a dark narrow twisting path to the eventual screenplay in which good sense and caution are thrown out the window and madness ensues.[22]

Unlike his previous and subsequent films, Brooks did not appear onscreen as himself in Young Frankenstein, though he recorded several voice parts and portrayed a German villager in one short scene. In 2012, Brooks explained why:

I wasn't allowed to be in it. That was the deal Gene Wilder had. He [said], "If you're not in it, I'll do it." [Laughs.] He [said], "You have a way of breaking the fourth wall, whether you want to or not. I just want to keep it. I don't want too much to be, you know, a wink at the audience. I love the script." He wrote the script with me. That was the deal. So I wasn't in it, and he did it.[23]

Filming

Mel Brooks wanted at least $2.3 million dedicated to the budget, whereas Columbia Pictures decided that $1.7 million had to be enough. Brooks instead went to 20th Century Fox for distribution, after they agreed to a higher budget.[24] Fox would later sign both Wilder and Brooks to five year contracts at the studio.

Principal photography began on February 19, 1974, and wrapped on May 3, 1974.[25] In one of the scenes of a village assembly, one of the authority figures says that they already know what Frankenstein is up to based on five previous experiences. On the DVD commentary track, Mel Brooks says this is a reference to the first five Universal films. In the Gene Wilder DVD interview, he says the film is based on Frankenstein (1931), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939) and The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942).[24]

Reception

Young Frankenstein was a box office success upon release. The film grossed $86.2 million on a $2.78 million budget.[3]

Young Frankenstein received critical acclaim from critics and currently holds a 94% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 64 reviews, with an average rating of 8.6/10. The consensus reads, "Made with obvious affection for the original, Young Frankenstein is a riotously silly spoof featuring a fantastic performance by Gene Wilder."[26]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "Mel Brooks' funniest, most cohesive comedy to date," adding, "It would be misleading to describe 'Young Frankenstein,' written by Mr. Wilder and Mr. Brooks, as astoundingly witty, but it's a great deal of low fun of the sort that Mr. Brooks specializes in."[27] Roger Ebert gave the film a full four stars, calling it Brooks' "most disciplined and visually inventive film (it also happens to be very funny)." [28] Gene Siskel gave the film three stars out of four and wrote, "Part homage and part send-up, 'Young Frankenstein' is very funny in its best moments, but they're all too infrequent."[29] Variety declared, "The screen needs one outrageously funny Mel Brooks film each year, and Young Frankenstein is an excellent followup for the enormous audiences that howled for much of 1974 at Blazing Saddles.'"[30]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times praised the film as "a likable, unpredictable blending of slapstick and sentiment."[31] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post, who disliked Blazing Saddles, reported being "equally untickled" with Young Frankenstein and wrote that "Wilder and Brooks haven't dreamed up a funny plot. They simply rely on the old movie plots to get them through a rambling collection of scene parodies and a more or less constant stream of puns, double entendres and other verbal rib-pokers and thigh-slappers."[32] Tom Milne of the UK's The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote in a mixed review that "all too often Brooks resorts to the most clichéd sort of Carry On smut" and criticized Marty Feldman's "grotesquely unfunny mugging," but praised a couple of sequences (the flower-throwing scene and the Monster's encounter with the blind man) as "very close to brilliance" and called Peter Boyle as the Monster "one of the undiluted pleasures of the film (he is the only actor ever to suggest that he might play the part as well as Karloff."[33]

Home media

Young Frankenstein was first released onto DVD November 3, 1998.[34] The film was released onto DVD the second time on September 5, 2006.[35] The film then released on DVD the third time on September 9, 2014 as a 40th anniversary edition along with the Blu-ray.[36]

Soundtrack

| Young Frankenstein | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album Dialogue & Music by Original cast | |

| Released | December 15, 1974 (LP) April 29, 1997 (CD) |

| Label | ABC Records (1974) One Way Records (1997) |

ABC Records released the soundtrack on LP on December 15, 1974. On April 29, 1997, One Way Records reissued it on CD. There are pieces of dialogue by the actors as well as background and incidental music on the disc. The LP and disc are now out of print and command a very high price on Internet auction sites when available.

Musical adaptation

Brooks adapted the film into a musical of the same name which premiered in Seattle at the Paramount Theatre and ran from August 7 to September 1, 2007.[37] The musical opened on Broadway at the Foxwoods Theatre (then the Hilton Theatre) on November 8, 2007 and closed on January 4, 2009. It was nominated for three Tony Awards, and starred Tony winner Roger Bart, two-time Tony winner Sutton Foster, Tony & Olivier winner Shuler Hensley, two-time Emmy winner Megan Mullally, three-time Tony nominee Christopher Fitzgerald, and two-time Tony & Emmy winner Andrea Martin.[38]

The musical version will be used as the basis of a live broadcast event on the ABC network in the last quarter of 2020, with Brooks producing.[39]

Awards

Nominations[40]

- Academy Award for Best Sound, Richard Portman and Gene Cantamessa (1975)

- Academy Award for Writing Adapted Screenplay, Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder (1975)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy, Cloris Leachman (1975)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture, Madeline Kahn (1975)

- WGA Award for Best Comedy Adapted from Another Medium, Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder (1975)

Cloris Leachman was nominated as a lead despite Madeline Kahn having far more screen time.

Wins

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, Young Frankenstein (1975)

- Nebula Award for Best Dramatic Writing, Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder (1976)

- Saturn Award for Best Horror Film, Young Frankenstein (1976)

- Saturn Award for Best Direction, Mel Brooks (1976)

- Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actor, Marty Feldman (1976)

- Saturn Award for Best Make-up, William Tuttle (1976)

- Saturn Award for Best Set Decoration, Robert De Vestel and Dale Hennesy (1976)

- Golden Screen Award, Young Frankenstein (1977)

- Toronto Film Festival Award for Best Comedic Film, Mel Brooks (1976)

Other honors

In 2011, ABC aired a primetime special, Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time, that counted down the best movies chosen by fans based on results of a poll conducted by ABC and People. Young Frankenstein was selected as the No. 4 Best Comedy.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Laughs – #13[41]

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Songs:

- "Puttin' on the Ritz" – #89[42]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes:

- Igor: "What hump?" – Nominated[43]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[44]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated[45]

References

- "Young Frankenstein". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- "Box Office Information for Young Frankenstein". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- "Young Frankenstein". GetBack Movie. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04.

- Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2009). Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914–2008. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-78-643332-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Picart, Caroline Joan (2003). Remaking the Frankenstein Myth on Film: Between Laughter and Horror. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-79-145770-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Film & Movie Comedy Classics". Comedy-Zone.net. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- "Bravo's 100 Funniest Movies". Bravo. Published by Lists of Bests. Archived from the original on April 5, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Laughs". American Film Institute. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- King, Susan (September 9, 2014). "'Young Frankenstein' has new life on 40th anniversary". Los Angeles Times.

'Young Frankenstein' is "by far the best movie I ever made. Not the funniest — 'Blazing Saddles' was the funniest, and hot on its heels would be 'The Producers.' But as a writer-director, it is by far my finest.

- Picart (2003), p. 46.

- Barnes, Mike (February 14, 2011). "Kenneth Mars, 'Young Frankenstein' Actor, Dies at 75". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Picart (2003), p. 54.

- Hallenbeck (2009), p. 108.

- Picart (2003), p. 61.

- Molinari, Matteo; Kamm, Jim (October 1, 2002). OOPS! They Did It Again!: More Movie Mistakes That Made the Cut. Google Books: Citadel. ISBN 978-0806523200.

- Joe Robberson (October 28, 2014). "20 Things You Didn't Know About 'Young Frankenstein'". Zimbio. Livingly Media. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Wilder, 140.

- Lacher, Irene. "The Sunday Conversation: Mel Brooks on his 'Young Frankenstein' musical". Los Angeles Times, August 1, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- Swinson, Brock (January 14, 2016). "Mel Brooks on Screenwriting". Creative Screenwriting. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Heisler, Steve (December 13, 2012). "Mel Brooks on how to play Hitler, and how he almost died making Spaceballs". The A.V. Club.

- Young Frankenstein – Mel Brooks Audio Commentary (DVD).

- https://www.latimes.com/visuals/photography/la-me-fw-archives-on-the-set-of-young-frankenstein-20181016-htmlstory.html

- "Young Frankenstein". Rotten Tomatoes.

- Canvy, Vincent (December 16, 1974). "'Young Frankenstein' a Monster Riot". The New York Times. 48.

- Ebert, Roger. "Young Frankenstein". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- Siskel, Gene (December 25, 1974). "'Young Frankenstein': Fitfully funny". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, p. 7.

- "Film Reviews: Young Frankenstein". Variety. December 18, 1974. 13.

- Champlin, Charles (December 18, 1974). "Portrait of a Young Monster". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- Arnold, Gary (December 21, 1974). "Monstrous Spoof". The Washington Post D1, D5.

- Milne, Tom (April 1975). "Young Frankenstein". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 42 (495): 90–91.

- "Young Frankenstein DVD". blu-ray.com. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Young Frankenstein DVD". blu-ray.com. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Young Frankenstein DVD". blu-ray.com. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "The Paramount official site". Theparamount.com. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- "Puttin' on the Glitz: Young Frankenstein Opens on Broadway". Playbill. November 8, 2007. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007.

- Evans, Greg (January 8, 2020). "ABC & Mel Brooks Will Team For 'Young Frankenstein Live!' This Fall – TCA". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- "The 47th Academy Awards (1975) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies Nominees (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Young Frankenstein |

- Young Frankenstein essay by Brian Scott Mednick at National Film Registry

- Young Frankenstein essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 713-714

- Young Frankenstein on IMDb

- Young Frankenstein at the TCM Movie Database

- Young Frankenstein at Box Office Mojo

- Young Frankenstein at Rotten Tomatoes