Yellow Submarine (song)

"Yellow Submarine" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by Paul McCartney and John Lennon, with lead vocals by Ringo Starr. It was included on their 1966 album Revolver and issued as a single, coupled with "Eleanor Rigby". The single went to number one on every major British chart, remained at number one for four weeks, and charted for 13 weeks. It won an Ivor Novello Award "for the highest certified sales of any single issued in the UK in 1966". In the US, the song peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, behind "You Can't Hurry Love" by the Supremes and it became the most successful Beatles song to feature Starr as lead vocalist.

| "Yellow Submarine" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

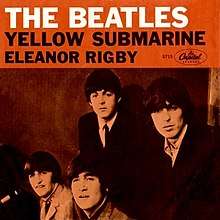

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| from the album Revolver | ||||

| A-side | "Eleanor Rigby" (double A-side) | |||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | |||

| Format | 7-inch record | |||

| Recorded | 26 May & 1 June 1966 | |||

| Studio | EMI, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:38 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Yellow Submarine" on YouTube | ||||

It became the title song of the animated United Artists film, also called Yellow Submarine (1968), and the soundtrack album to the film, released as part of the Beatles' music catalogue. An orchestral reprise to the song arranged by George Martin titled "Yellow Submarine in Pepperland" is featured at the end of the film and its soundtrack.

Although intended as a nonsense song for children, "Yellow Submarine" received various social and political interpretations at the time of its release.[4]

Composition

In a joint interview in March 1967, McCartney and Lennon recalled that the song's melody was created by combining two different songs they had been working on separately. Lennon noted that McCartney brought in the chorus ("the submarine... the chorus bit") which Lennon suggested combining with a melody for the verses that he'd already written.[5] McCartney also noted: "It's a happy place, that's all. You know, it was just ... We were trying to write a children's song. That was the basic idea. And there's nothing more to be read into it than there is in the lyrics of any children's song."[6][7]

In 1980, Lennon talked further about the song: "'Yellow Submarine' is Paul's baby. Donovan helped with the lyrics. I helped with the lyrics too. We virtually made the track come alive in the studio, but based on Paul's inspiration. Paul's idea. Paul's title ... written for Ringo."[6] Donovan added the words, "Sky of blue and sea of green".[8][9]

In 1994, McCartney discussed his inspiration for the song's concept:[10] "I was laying in bed in the Ashers' garret ... I was thinking of it as a song for Ringo, which it eventually turned out to be, so I wrote it as not too rangey in the vocal, then started making a story, sort of an ancient mariner, telling the young kids where he'd lived. It was pretty much my song as I recall ... I think John helped out. The lyrics got more and more obscure as it goes on, but the chorus, melody and verses are mine."[6] The song began as being about different coloured submarines, but evolved to include only a yellow one.[11]

Recording

Produced by George Martin and engineered by Geoff Emerick, "Yellow Submarine" was recorded in five takes on 26 May 1966, in Studio Two at Abbey Road Studios; special effects were added on 1 June.[8] Martin drew on his experience as a producer of comedy records for Beyond the Fringe and members of the cast of The Goon Show, providing an array of zany sound effects to create the nautical atmosphere.[12] On the second session the studio store cupboard was ransacked for special effects, which included chains, a ship's bell, tap dancing mats, whistles, hooters, waves, a tin bath filled with water, wind, and thunderstorm machines, as well as a cash register, which was the very same one later heard on Pink Floyd's song "Money" (1973).[13] Lennon blew through a straw into a pan of water to create a bubbling effect; McCartney and Lennon talked through tin cans to create the sound of the captain's orders; at 1:38–1:40 in the song, Starr stepped outside the doors of the recording room and yelled like a sailor, acknowledging "Cut the cable! Drop the cable!", which was looped into the song afterwards; and Abbey Road employees John Skinner and Terry Condon twirled chains in a tin bath to create water sounds.[8] After the line, "and the band begins to play", Emerick found a recording of a brass band and changed it slightly so it could not be identified, although it is thought to be a recording of Georges Krier and Charles Helmer's composition, "Le Rêve Passe" (1906).[8] The original recording had a spoken intro by Starr, but the idea was abandoned on 3 June.[8]

When the overdubs were finished, Mal Evans strapped on a marching bass drum and led everybody in a line around the studio doing the conga dance whilst banging on the drum.[13]

Release

The "Yellow Submarine" single was the Beatles' 13th single release in the United Kingdom. It was released in the UK on 5 August 1966 as a double A side with "Eleanor Rigby", and in the United States on 8 August. In both countries, the album Revolver, which featured both songs, was released on the same day as the single.[14] On 6 July 2018, a 7-inch vinyl picture disc was released to mark the 50th anniversary of the release of the film based on the song, although the reissue used the stereo remixes made for the 1 album's 2015 release.[15]

Reception and interpretations

The single went to number 1 on every major British chart, remained at number 1 for four weeks and charted for 13 weeks.[8] It won an Ivor Novello Award for the highest certified sales of any single issued in the UK in 1966.

In the United States, the single reached number 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 (behind "You Can't Hurry Love" by the Supremes) and number 1 in Record World and in Cash Box.[16] The single was released during the controversies about the "Butcher Cover" (the Yesterday and Today album cover)[8] and "More popular than Jesus" remarks,[17] which are cited as part of the reason the song failed to reach number 1 on all US charts. It sold 1,200,000 copies in four weeks and earned the Beatles their twenty-first US Gold Record award, beating the record set by Elvis Presley. According to Beatles biographer Nicholas Schaffner, a teenager at the time: "Whether you loved it or hated it, the 'Yellow Submarine,' once lodged in the brain, was impossible to get rid of. Everywhere you went in the latter half of 1966, you could hear people whistling it."[18]

Although intended as a nonsense song for children, "Yellow Submarine" received various social and political interpretations at the time. Music journalist Peter Doggett wrote that the "culturally empty" song "became a kind of Rorschach test for radical minds".[4] The song's chorus was reappropriated by schoolchildren, sports fans, and striking workers in their own chants. At a Mobe protest in San Francisco, a yellow papier-mâché submarine made its way through the crowd, which Time magazine interpreted as a "symbol of the psychedelic set's desire for escape".[4] A reviewer for the P.O. Frisco wrote in 1966, "the Yellow Submarine may suggest, in the context of the Beatles' anti-Vietnam War statement in Tokyo this year, that the society over which Old Glory floats is as isolated and morally irresponsible as a nuclear submarine."[4] Writing for Esquire, Robert Christgau felt that the Beatles "want their meanings to be absorbed on an instinctual level" and wrote of the interpretations: "I can't believe that the Beatles indulge in the simplistic kind of symbolism that turns a yellow submarine into a Nembutal or a banana – it is just a yellow submarine, damn it, an obvious elaboration of John [Lennon]'s submarine fixation, first revealed in A Hard Day's Night."[19]

Personnel

According to Ian MacDonald:[20]

The Beatles

- Ringo Starr – lead vocal, drums

- John Lennon – acoustic guitar, backing vocals, sound effects (bubbles)

- Paul McCartney – bass guitar, backing vocals

- George Harrison – acoustic guitar, tambourine, backing vocals

Additional contributors

- Mal Evans – bass drum, backing vocals

- George Martin – backing vocals, producer

- Geoff Emerick – backing vocals, tape loops, engineer

- Neil Aspinall – backing vocals

- Alf Bicknell – sound effects (rattling chains)

- Pattie Boyd – backing vocals

- Marianne Faithfull – backing vocals

- Brian Jones – backing vocals, sound effects (clinking glasses)

- Brian Epstein – backing vocals

Charts and certifications

Charts

|

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

A 51-foot (16 m)-long yellow submarine metal sculpture was built by apprentices from the Cammell Laird shipyard, and was used as part of Liverpool's International Garden Festival in 1984. In 2005, it was placed outside Liverpool's John Lennon Airport, where it remains. There is a Yellow Submarine boat hotel currently moored near Liverpool's Albert Dock. The Beatles-themed Yellow Sub Bar, which is built to look like the film's submarine, is currently open and located in Liverpool's Baltic Triangle area on Stanhope Street.

Yellow Submarine has entered popular usage as a sing-along children's song, such as in Playdays and Fun Song Factory, when it was once combined with colourful props and actions, on Zoom, where the child performers portrayed the submarine's crew while singing the song, and on Sesame Street, where a group of Anything Muppets sang the song inside a yellow submarine that resembled the one from the animated film.

The tune of the song has been used in Britain and America by those protesting government actions, with the lyrics changed to "we all live in a Fascist regime".[37][38][39][40]

Notes

- "The Beatles Album Review". Condé Nast. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Cohen, Norm (2005). Folk Music: A Regional Exploration. Greenwood Press. p. 335. ISBN 0-313-32872-2.

- "The Beatles Revolver Review". BBC. 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Doggett, Peter (6 May 2009). There's a Riot Going On: Revolutionaries, Rock Stars, and the Rise and Fall of the '60s. Canongate U.S. pp. 107–108. ISBN 1-84767-193-4.

- "Lennon & McCartney Interview: Ivor Novello Awards, 3/20/1967". Beatles Interviews Database. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Beatles Interview Database 2008.

- Gilliland 1969, show 39, track 2.

- Fontenot 1999.

- Leitch, Donovan (2005). The Autobiography of Donovan. St. Martin's Press. p. 153.

- Miles 1998, p. 106.

- Turner 2005, p. 109.

- "74 - Yellow Submarine". 100 Greatest Beatles Songs. Rolling Stone.

- Spitz 2005, p. 612.

- Spitz 2005, p. 629.

- Beatles.com

- Cash Box

- Spitz 2005, p. 627.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 62.

- Christgau, Robert (December 1967). "Columns: December 1967". Esquire. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- MacDonald 2005, p. 206.

- "Yellow submarine in Australian Chart". Poparchives.com.au. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Austriancharts.at – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40.

- "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50.

- "Yellow submarine in Canadian Top Singles Chart". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Yellow submarine in Irish Chart". IRMA. Retrieved 17 July 2013. Only one result when searching "Yellow submarine"

- "Nederlandse Top 40 – The Beatles" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine / Eleanor Rigby" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- "flavour of new zealand - Home (23 September 1966)". www.flavourofnz.co.nz. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". VG-lista.

- Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959-2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- "Swedish Charts 1966–1969/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka > Augusti 1966" (PDF) (in Swedish). hitsallertijden.nl. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- "Beatles". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 22 February 2019. To see peak chart position, click "TITEL VON The Beatles"

- "50 Back Catalogue Singles – 27 November 2010". Ultratop 50. Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "American single certifications – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 14 May 2016. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Single, then click SEARCH.

- Robert Booth (29 April 2011). "Royal wedding: police criticised for pre-emptive strikes against protesters". The Guardian.

- Carl O'Brien (7 July 2005). "Three Irish mammies in vanguard of demonstration". The Irish Times.

- Philip Marsh (15 May 2015). "No One Would Riot for Less: the UK General Election, "Shy Tories" and the Eating of Lord Ashdown's Hat". The Weeklings.

- Rachel Campbell (21 January 2005). "Feeling blue about the inauguration". The Journal Times.

References

- "Badmeaningood 2". MTV. 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fontenot, Robert (20 August 1999). "Yellow Submarine". About.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The Rubberization of Soul: The great pop music renaissance" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewisohn, Mark (1988). The Beatles Recording Sessions. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-57066-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico (Rand). ISBN 1-84413-828-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, George; Hornsby, Jeremy (1994). All You Need Is Ears. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-11482-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Maurice Chevalier - de "Valentine" à "Yellow Submarine"". Database.cd. 2008. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- "Maurice Chevalier Songs". Allmusic. 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Steve (2005). A Hard Day's Write (Third ed.). HarperResource. ISBN 0-06-273698-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Yellow Submarine". Beatles Interview Database. 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Revolver (Beatles album) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yellow Submarine. |