Wildlife smuggling and zoonoses

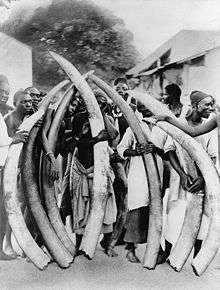

Wildlife trafficking practices have resulted in the emergence of zoonotic diseases. Exotic wildlife trafficking is a multi-billion dollar industry that involves the removal and shipment of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and fish all over the world.[1] Traded wild animals are used for bushmeat consumption, unconventional exotic pets, animal skin clothing accessories, home trophy decorations, privately owned zoos, and for traditional medicine practices. Dating back centuries, people from Africa,[2][3] Asia,[4][5][6][7] Latin America,[8][9] the Middle East,[10] and Europe[11] have used animal bones, horns, or organs for their believed healing effects on the human body. Wild tigers, rhinos, elephants, pangolins, and certain reptile species are acquired through legal and illegal trade operations in order to continue these historic cultural healing practices. Within the last decade nearly 975 different wild animal taxa groups have been legally and illegally exported out of Africa and imported into areas like China, Japan, Indonesia, the United States, Russia, Europe, and South America.[12]

.jpg)

Consuming or owning exotic animals can propose unexpected and dangerous health risks. A number of animals, wild or domesticated, carry infectious diseases and approximately 75% of wildlife diseases are vector-borne viral zoonotic diseases.[13] Zoonotic diseases are complex infections residing in animals and can be transmitted to humans. The emergence of zoonotic diseases usually occurs in three stages. Initially the disease is spread through a series of spillover events between domesticated and wildlife populations living in close quarters. Diseases then spread through series of direct contact methods, indirect contact methods, contaminated foods, or vector-borne transmissions. After one of these transmission methods occurs, the disease then rises exponentially in human populations living in close proximities.[14] After the appearance of the COVID-19 pandemic, said to have originated by this method at Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, the acting executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, called for a global ban on wildlife markets to prevent future pandemics.[15] Others called for already existing bans to be enforced, in order both to reduce cruelty to animals as well as to reduce health risks to humans.[16][17]

Types of zoonotic disease transmissions

Direct contact transmissions occur when humans encounter first hand contaminated feces, urine, water sources, or bodily fluids. Bodily fluid transmission may happen either from ingesting pathogens or through open wound contact. Indirect contact transmissions occur when humans interact within an infected species' habitat. Humans are often exposed to contaminated soils, plants, and surfaces where bacterial germs are present. Contaminated food transmissions occur when humans eat infected bushmeat, vegetables, fruits, or drink contaminated water. Often these food and water supplies are tainted by fecal pellets of infected bats, birds, or monkeys. Vector-borne transmissions occur when individuals are bitten by infected parasites such as ticks or insects like mosquitos and fleas.[18]

Other factors for escalated disease transmissions include climate change, globalization of trade, accelerated logging practices, irrigation increases, sexual activity between individuals, blood transfusions, and urbanization developments near infected ecosystems.[19]

Health risks of zoonotic diseases

Exotic wildlife trafficking admits a number of infectious diseases that spell potential life-threatening results for human populations if contracted. Researchers believe eliminating the transmission of infectious diseases is not plausible. Instead, creating health screening services is critical for minimizing transmission rates among populations and infected wildlife species involved in trafficking.

Annually, 15.8% of human deaths have been associated with dangerous infectious disease outbreaks linked to exotic trafficking.[20] Researchers, zoologists, and environmentalists determine that financially poor countries in Africa may attribute to nearly 44% of these deaths due to zoonosis related diseases.[20]

Cultural determinants linking Africa to disease exposure

People in Africa are exposed to an increased risk of contracting and dispatching life-threatening zoonotic infections. The continent is considered a hot spot for emerging disease transmissions for reasons like socio-culture livelihood interests, livestock farming, land use methods, globalization influences, and consumption behavior practices.[21]

Socio-Culture livelihood factors

Many Africans make a living from the wildlife trade due to the high market demand for exotic animals. These individuals partaking in poaching activities are able to produce an income by selling to vendors all around the world. However, hunters are highly susceptible to encountering infected droplets, water sources, soils, carcasses, and viral airborne pathogens while traveling through the bush. Once they have successfully hunted and killed the wild animal, they run the risk of blood or bodily fluid transfer from close contact with possible infected species. They're also at an increased risk of harvesting arthropod-borne pathogens carried in ticks. Often ticks can be found on the wild animal or in its surrounding wildlife habitat.[22]

Livestock and land use methods

Potential increases in zoonotic disease transmissions have been associated with rising population numbers in both livestock and humans. Numerous African societies make their livelihoods from practicing pastoralism and traditional farming methods. In some cases infected wildlife sharing the same environment may come into contact with livestock and pass on these viral pathogens. Different zoonotic infections can intensify while residing in wild or domesticated animals and present deadly spillover into humans populations. Researchers believe future emergences of zoonotic diseases will be directly linked to agricultural and livestock farming methods.

A study conducted in Tanzania revealed major gaps in locals knowledge of zoonotic diseases. Individuals in these pastoral communities acknowledged health symptoms commonly found in both humans and animals, however they did not have a synthesized term for zoonosis and believed pathogens were not life-threatening. Researchers found that the pastoral communities were more concerned with keeping cultural practices of producing cooked meals rather than the potential infections harvested from the animals.[21]

Globalization influence

A number of globalization threats have negatively impacted Africa's environmental habitats, biodiversity counts, and overall climate change. Developing urbanized landscapes requires deforestation. As a result, biodiversity counts decrease and growing human populations encroach further into the ecosystems of wildlife.

Urbanization impact on a region's biodiversity presents a serious issue. Landscapes inhabiting smaller biodiversity counts are more susceptible to rapid disease spread. Areas with a larger species diversity are more capable of reducing disease dispersal due to the number of possible hosts.

Logging patterns in Africa have grown exponentially over the years. Around 90% of the continent's individuals use wood as their primary energy source for preparing food and others use it for timber global trading purposes.[23] With fewer trees, carbon dioxide and global greenhouse emissions are increasing and negatively affecting climate change.

Urbanizing new environments in Africa also increases the migration patterns of humans. New settlements and tourist attractions near these wildlife habitats bring vulnerable individuals with no disease immunity closer to areas of diseases.[21]

Consumption behaviors

The greatest possibility of contracting deadly zoonotic diseases occurs during the bushmeat cooking process. Cooking exotic bushmeat requires sharp knives, steady handwork, and skilled techniques when correctly butchering an animal. Consumers often purchase bushmeat directly from African poachers. This means they have no way of knowing whether the wild animal is carrying dangerous zoonotic pathogens. On average people cut themselves 38% of the time when butchering bushmeat, allowing for infected bodily fluid transmissions. African women are more likely to contract these dangerous zoonotic pathogens because they are the ones handling and cooking the bushmeat.[22]

Exotic trade and disease outbreaks

Ebola virus disease is a rare infectious disease that is likely transmitted to humans by wild animals. The natural reservoirs of Ebola virus are unknown, but possible reservoirs include fruit bats, non-human primates,[24] rodents, shrews, carnivores, and ungulates.[25]

Transmission of this virus likely occurs when individuals live closely to infected habitats, exchange bodily liquids, or consume infected animals.[26] West Africa's Ebola outbreak was termed the most destructive infectious disease epidemic in recent history, killing a total of 16,000 individuals between 2014 and 2015. Wildlife poachers have the greatest chance of contracting and dispersing this disease at they return from the bush.[27]

HIV is a life-threatening virus that attacks the immune system. The virus weakens the white blood cell count and their ability to detect and ward off potentially harmful diseases. Dispersal of the disease includes acts of consuming infected bushmeat, pathogens coming into contact with open wounds, and through infected blood transfers.[28] The two major strains of HIV, HIV-1 and HIV-2, are both believed to have originated in West or Central Africa from strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), which infects various non-human primate species. Some of these primates affected by SIV are often hunted and trafficked for bushmeat, traditional medicine practices, and for exotic pet trade purposes.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), often referred to as a severe form of pneumonia, is a highly contagious zoonotic respiratory illness causing extreme breathing difficulties. Factors attributing to widespread dispersal include the destruction of wildlife natural ecosystems, overextended urbanization effects on biodiversity, and contact with bacterially contaminated objects.[29] The virus originated in tropical areas of Africa and Southeast Asia and is linked to their native bats and civets. Civet wildlife trade in Southeast Asian and African markets have been monitored to reduce the risk of future pathogen spread through spillover events.

Monkeypox is a viral zoonotic double stranded DNA disease that occurs in both humans and animals. It often accumulates in wild animals and is transmitted by close contact within animal trade.[30] It is most commonly found in central and west Africa where it is carried in a number of infected species including monkeys, apes, rats, prairie dogs, and other small rodents.[31] In an attempt to reduce the rate of disease spread, researchers believe minimizing direct and indirect contact rates between species in wildlife trade markets is the most practical solution.[32]

Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and is transmitted through open wound contact or exposure to contaminated bodily fluids. Oriental rat fleas, which are thought to originate in northern Africa carry the bacteria and transmit the disease by biting and infecting both humans and wild animals.[33] Small African rodents harbor this disease and infect prairies, wildlife markets, and other areas where large African primates and carnivores are hunted for bushmeat and exotic trade purposes.

Marburg virus, which causes Marburg virus disease, is a zoonotic RNA virus within the filovirus family. It is closely related to the Ebola virus and is transmitted by wild animals to humans. African monkeys and fruit bats are believed to be the main carries of the infectious disease. In 2012 the most recent outbreak occurred in Uganda, where fifteen individuals contracted the disease and four ultimately died from elevated hemorrhagic fevers. Rising numbers of deforestation, urbanization, and exotic animal trade have increased the likeliness of spreading this viral disease.[34]

West Nile virus is a single stranded RNA virus that can cause neurological diseases within humans. The first outbreak was recorded in Uganda and other areas of West Africa in 1937. Disease transmission is primarily through mosquitos feeding on infected dead birds. The infection then circulates within the mosquito and is transferred to humans or animals when bitten by the infected insect.[35]

African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness is caused by a microscopic parasite called the Trypanosoma brucei, which is transferred to humans and animals through the bite of a tsetse fly.[36] The disease is a reoccurring issue in many rural parts of Africa and over 500,000 individuals currently carry the disease. Livestock, game animals, and wild species of the bush are prone to the infection. Wildlife game markets and other exotic animal trade methods continue to spread transmission. These trade operations have introduced dangerous repercussions as the disease becomes more adaptive to drug resistance.[37]

See also

- Global catastrophic risk – Hypothetical future events that could damage human well-being globally

- Globalization and disease – Overview of globalization and disease transmission

- Pandemic prevention – The organization and management of preventive measures against pandemics

- Virgin soil epidemic – worse effects of disease to populations with no prior exposure

- Wet market – Market selling perishable goods, including meat, produce, and food animals

References

- Ashley S, Brown S, Ledford J, Martin J, Nash AE, Terry A, Tristan T, Warwick C (2014-10-02). "Morbidity and mortality of invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals at a major exotic companion animal wholesaler". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 17 (4): 308–21. doi:10.1080/10888705.2014.918511. PMID 24875063.

- "Traditional-Medical Knowledge and Perception of Pangolins (Manis sps) among the Awori People, Southwestern Nigeria" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2011.

- "Reptiles used in traditional folk medicine: conservation implications" (PDF). Springer. 2008.

- Costa-Neto, Eraldo M. (2005). "Animal-based medicines: biological prospection and the sustainable use of zootherapeutic resources". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 77 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652005000100004. ISSN 0001-3765.

- Jugli, Salomi; Chakravorty, Jharna; Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (2019-06-15). "Zootherapeutic uses of animals and their parts: an important element of the traditional knowledge of the Tangsa and Wancho of eastern Arunachal Pradesh, North-East India". Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi:10.1007/s10668-019-00404-6. ISSN 1573-2975.

- Nijman V (2010-04-01). "An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia". Biodiversity and Conservation. 19 (4): 1101–1114. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4. ISSN 1572-9710.

- Zhang L, Hua N, Sun S (2008-06-01). "Wildlife trade, consumption and conservation awareness in southwest China". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17 (6): 1493–1516. doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9358-8. ISSN 1572-9710. PMC 7088108.

- Alves, Rômulo RN; Alves, Humberto N. (2011-03-07). "The faunal drugstore: Animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 7 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-7-9. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 3060860. PMID 21385357.

- Souto, Wedson Medeiros Silva; Barboza, Raynner Rilke Duarte; Fernandes-Ferreira, Hugo; Júnior, Arnaldo José Correia Magalhães; Monteiro, Julio Marcelino; Abi-chacra, Érika de Araújo; Alves, Rômulo Romeu Nóbrega (2018-09-17). "Zootherapeutic uses of wildmeat and associated products in the semiarid region of Brazil: general aspects and challenges for conservation". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 14 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s13002-018-0259-y. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 6142313. PMID 30223856.

- "Zootherapy: A study from the Northwestern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan" (PDF). Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2016.

- "A COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF ZOOTHERAPEUTIC REMEDIES FROM SELECTED AREAS IN ALBANIA, ITALY, SPAIN AND NEPAL" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 2010.

- Rosen GE, Smith KF (August 2010). "Summarizing the evidence on the international trade in illegal wildlife". EcoHealth. 7 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1007/s10393-010-0317-y. PMC 7087942. PMID 20524140.

- Pfeffer M, Dobler G (April 2010). "Emergence of zoonotic arboviruses by animal trade and migration". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-35. PMC 2868497. PMID 20377873.

- Tsai P, Scott KA, Gonzalez MC, Pappaioanou M, Keusch GT, et al. (National Research Council (US) Committee on Achieving Sustainable Global Capacity for Surveillance and Response to Emerging Diseases of Zoonotic Origin) (2009). Drivers of Zoonotic Diseases. National Academies Press (US).

- Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Bonyhady, Nick (4 April 2020). "Canberra to push China to ban wildlife meat trade". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Raven, Peter H. (June 1, 2020). "Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction". PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922686117.

The horrific coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic that we are experiencing, of which we still do not fully understand the likely economic, political, and social global impacts, is linked to wildlife trade. It is imperative that wildlife trade for human consumption is considered a gigantic threat to both human health and wildlife conservation. Therefore, it has to be completely banned, and the ban strictly enforced, especially in China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and other countries in Asia

- May C. "Transmission Routes of Zoonotic Diseases" (PDF).

- Lindahl JF, Grace D (2015-11-27). "The consequences of human actions on risks for infectious diseases: a review". Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. 5: 30048. doi:10.3402/iee.v5.30048. PMC 4663196. PMID 26615822.

- Salyer SJ, Silver R, Simone K, Barton Behravesh C (December 2017). "Prioritizing Zoonoses for Global Health Capacity Building-Themes from One Health Zoonotic Disease Workshops in 7 Countries, 2014-2016". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (13): S55–S64. doi:10.3201/eid2313.170418. PMC 5711306. PMID 29155664.

- Aguirre AA (December 2017). "Changing Patterns of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases in Wildlife, Domestic Animals, and Humans Linked to Biodiversity Loss and Globalization". ILAR Journal. 58 (3): 315–318. doi:10.1093/ilar/ilx035. PMID 29253148.

- Francesco A (December 2016). "Bushmeat and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Africa". ResearchGate.

- "Deforestation in Sub-Saharan Africa". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- "What is Ebola Virus Disease?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Olivero, Jesús; Fa, John E.; Real, Raimundo; Farfán, Miguel Ángel; Márquez, Ana Luz; Vargas, J. Mario; Gonzalez, J. Paul; Cunningham, Andrew A.; Nasi, Robert (2017). "Mammalian biogeography and the Ebola virus in Africa" (PDF). Mammal Review. 47: 24–37. doi:10.1111/mam.12074.

We found published evidence from cases of serological and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positivity of EVD in non- human mammal, or of EVD-linked mortality, in 28 mammal species: 10 primates, three rodents, one shrew, eight bats, one carnivore, and five ungulates

- "Ebola virus disease". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- Egbetade AO, Sonibare AO, Meseko CA, Jayeola OA, Otesile EB (2015-10-11). "Implications of Ebola virus disease on wildlife conservation in Nigeria". The Pan African Medical Journal. 22 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): 16. doi:10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6617 (inactive 2020-01-22). PMC 4695512. PMID 26740844.

- "What is HIV? - HIV/AIDS". www.hiv.va.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- "WHO | SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)". WHO. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- "Monkeypox". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- "Monkeypox" (PDF). The Center for Food Security & Public Health. Iowa State University.

- Karesh WB, Cook RA, Bennett EL, Newcomb J (July 2005). "Wildlife trade and global disease emergence". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1000–2. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194. PMC 3371803. PMID 16022772.

- "History of the Plague | Plague | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- "Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-25. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Colpitts TM, Conway MJ, Montgomery RR, Fikrig E (October 2012). "West Nile Virus: biology, transmission, and human infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 25 (4): 635–48. doi:10.1128/CMR.00045-12. PMC 3485754. PMID 23034323.

- "CAB Direct". www.cabdirect.org. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Paone M, Franco JR, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Fèvre EM, Courtin F, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG (November 2010). "The Atlas of human African trypanosomiasis: a contribution to global mapping of neglected tropical diseases". International Journal of Health Geographics. 9 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-9-57. PMC 2988709. PMID 21040555.