Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? (British game show)

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? is a British television quiz show, created and formerly produced by David Briggs, and made for the ITV network. On air since September 1998 and devised by Briggs, the show's format sees contestants taking on multiple-choice questions based upon general knowledge, winning a cash prize for each question they answer correctly, with the amount offered increasing as they take on more difficult questions. To assist each contestant who takes part, they are given lifelines to use, may walk away with the money they already have won if they wish not to risk answering a question, and are provided with a safety net that gives them a guaranteed cash prize if they give an incorrect answer, provided they reach a specific milestone in the quiz.

| Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? | |

|---|---|

Titlecard for the revived series of the show | |

| Genre | Quiz show |

| Created by |

|

| Presented by |

|

| Theme music composer |

|

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of series | 34 |

| No. of episodes | 630 |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) | Fiona Clark (2018–present) |

| Production location(s) |

|

| Running time | 30–80 minutes |

| Production company(s) |

|

| Distributor | Celador International/2waytraffic International (1998–2009) Sony Pictures Television International Distribution (2009–2014, 2018–present) |

| Release | |

| Original network | ITV |

| Picture format | 4:3 (1998–1999) 16:9 (1999–present) |

| Original release | Original series: 4 September 1998 – 11 February 2014 Revived series: 5 May 2018 – present |

| External links | |

| Website | |

The original series aired for 30 series and aired a total of 592 episodes, from 4 September 1998 to 11 February 2014, and was presented by Chris Tarrant. Over the course of its initial run, the show had five contestants achieve the ultimate aim and walk away with the cash prize of £1 million. The original format of the programme was tweaked in later years; this included changing the number of questions from fifteen to twelve, altering the payout structure and later incorporating a time limit which included an attainable fourth lifeline. There were several controversies during its run, including an attempt by a contestant to defraud the show of its top prize.

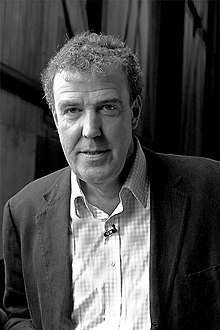

Four years after the original series ended, ITV announced that the series would be revived, this time produced by Stellify Media, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the programme. The revival was based closely on the show’s original format. It was hosted by Jeremy Clarkson and filmed at Dock10 studios. The success of the revival series has ensured that subsequent series of the show have been commissioned, and in January 2019 the show reached the milestone of 600 episodes since first appearing on air.

The game show became one of the most significant shows in British popular culture, ranking 23rd in a list of the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes compiled in 2000 by the British Film Institute. It was the highest quiz programme to appear on the list. Its success led to versions in many other countries under an international franchise of the same name, all of which follow the same general format, though with some versions including unique differences in gameplay and lifelines provided.

History

Creation

The creation of the game show was led by David Briggs, assisted by Mike Whitehill and Steven Knight, who had helped him before with creating a number of promotional games for Chris Tarrant's morning show on Capital FM radio. The basic premise for the show was a twist on the conventional game-show genre of the time: the programme would have just one contestant answering questions; they would be allowed to pull out at any time, even after they had seen the question and the possible answers; and they had three opportunities to receive special forms of assistance.

During the design phase, the show was given the working title of "Cash Mountain", before Briggs decided upon using the name of the song written by Cole Porter for the 1956 film High Society, as the show's finalised title.[1] After presenting their idea to ITV, the broadcaster gave the green light for production to begin on a series.

The set designed for Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? was conceived by British production designer Andy Walmsley, who focused the design towards making contestants feel uncomfortable, creating an atmosphere of tension similar to a movie thriller.[2] The design was in stark contrast to the design of sets made for more typical game shows, which are designed to make contestants feel more at ease.[1] Walmsley's design feature a central stage made primarily with Plexiglas, with a huge dish underneath covered in mirror paper,[2][1] onto which two slightly-modified, 3 foot (0.91 m)-high Pietranera Arco All chairs were chosen for use by both the contestant and the host, each having an LG computer monitor directly facing each that would be used to display questions and other pertinent information. The rest of the set featured seating spaced out around the main stage in a circle, with breaks in them to allow movement of people on and off the set. The lighting rig used for the set was designed so as to allow only the lights to switch from illuminating the entire set, to focusing on the host and contestant on the main stage when a game was underway, but to include special lighting effects when the contestant reached higher cash prize amounts. His overall conception would eventually prove to be a success, becoming one of the most reproduced scenic designs in television history.[2]

The music provided for the show was composed by father-and-son duo Keith and Matthew Strachan. The Strachans' composition for the game show helped with Briggs' tense game design, by providing the necessary drama and tension. Unlike other game show musical scores, the music provided for Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? was designed to be played throughout the entire episode of the show. The Strachans main theme for the game show was inspired from the "Mars" movement of Gustav Holst's The Planets. For the main game of the show, the pair designed the music to feature three variations, with the second and third compositions focused on emphasising the increased tension of the game – as a contestant made progress to higher cash amounts, the pitch of the music was increased by a semitone for each subsequent question.[3] On Game Show Network's Gameshow Hall of Fame special, the narrator described the Strachan tracks as "mimicking the sound of a beating heart", and stated that as the contestant works their way up the money ladder, the music is "perfectly in tune with their ever-increasing pulse".[1]

Original series (1998–2014)

With the show created, ITV assigned Chris Tarrant as its host, and set its premiere to 4 September 1998. The programme was assigned a timeslot of one hour, to provide room for three commercial breaks, with episodes produced by UK production company Celador. Originally, the show was broadcast on successive evenings for around ten days, before the network modified its broadcast schedule in autumn 2000[4] to air it within a primetime slot on Saturday evenings, with occasional broadcasts on Tuesday evenings. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? proved a ratings hit, pulling in average viewing figures of up to 19 million during its broadcast in 1999 (all-time high was on 7 March 1999, 19.2 million viewers),[4] though such figures often occurred when the programme was allocated to a half-hour timeslot. By September 2000 viewing figures had dropped to 11.1 million viewers,[4] and by 2003 to an average of around 8 million viewers.[5] Audiences continued to drop[6] and from 2005 to 2011 the show usually attracted between 3 and 4 million viewers.[7][8][9] At one point in September 1999, an episode had 60% of the TV share and caused the BBC an historic low in ratings.[4] Over the course of his time presenting the game show, Tarrant developed a number of notable catchphrases. Notable ones include "Audience, all on your keypads please. All Vote Now!" said when the 'Ask the Audience' lifeline is used; "Is that your final answer?", often said to confirm the contestants answer choice and "But we don't want to give you that", when displaying the contestant current winning cheque, to urge them on to win more money.

Since its launch, several individuals made claims over the origins of the format or elements of it, with each accusing Celador of breaching their copyrights. In three cases, the matters could not be proven by the claimants – in 2002, Mike Bull, a Southampton-based journalist, was given an out-of-court settlement when he claimed the authorship of lifelines was his work, though with a confidentiality clause attached; in 2003, Sydney resident John J. Leonard made claims in that the show's format was based on one he had made of a similar nature, but without the concept of lifelines;[10][11] in 2004, Alan Melville was given an out-of-court settlement after he claimed that the opening phrase "Who wants to be a millionaire?" had been taken from a document he sent to Granada Television, concerning his idea for a game show based on the lottery.

One of most significant claims Celador received against them was from John Bachini. In 2002, he started legal proceedings against the production company, ITV, and five individuals who had claimed they had created Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, stating that the idea from the show was taken from several elements he had created – a board game format he conceived in 1981; a two-page TV format, known as Millionaire, made in 1987; and the telephone mechanics for a TV concept he created in 1989, BT Lottery. In his claim, Bachini stated that he submitted documents for his TV concepts to Paul Smith, from a sister company of Celador's, in March 1995 and again in January 1996, and to Claudia Rosencrantz of ITV, also in January 1996, accusing both of using roughly 90% of the format for Millionaire in the pilot for the game show, including the use of twenty questions, lifelines and safety nets, although the lifelines were conceived under different names – Bachini claimed that he never coined the phrase "phone-a-friend" that Briggs designed in his format. In response to this claim, Celador made a counter-claim that the franchise originated from the basic format idea conceived by Briggs. The defendants in the claim took Bachini to a summary hearing but lost their right to have his claim dismissed. Although Bachini won the right to go to trial, he was unable to after the hearing due to serious illness. Celador eventually settled the matter with him out-of-court.[12]

In March 2006, Celador began procedures to sell the format of the show and all UK episodes, as part of their first step towards the sale of their formats divisions. The purchase of both assets was made by Dutch company 2waytraffic,[13] which were then passed on to Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2008 when it acquired 2waytraffic.[14] As the original series progressed, variations of the format were created, and screened as special episodes, including celebrity editions, games featuring couples as contestants, and episodes themed around special events such as Mother's Day.

The Christmas Eve celebrity special from December 2010 drew its biggest audience since 2006. To capitalise on this, and breathe new life into the now 12-year-old show,[15] from April 2011 only celebrity contestants appeared on the show, in special live editions that coincided with holidays, events and other notable moments, such as the end of a school term. However, in 2012, three special episodes, entitled "The People Play", were broadcast for three consecutive nights between 9 and 11 July. They featured standard contestants, with viewers at home allowed to play along.[16] The special was used three more times in 2013, once on 7 May, and twice more on 21 May, before the special's format was discontinued.

On 22 October 2013, Tarrant announced that, after fifteen years of hosting the programme, he would be leaving Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, which consequently led ITV to axe the programme once his contract was finished; no more specials would be filmed after this announcement, leaving only those made before it to be aired as the final episodes.[17][18] After a few more celebrity editions of the game show, Tarrant hosted his final episode, a clip show entitled "Chris' Final Answer", which aired on 11 February 2014.[19]

Revival (2018–present)

In 2018, ITV revived the show for a new series, as part of its 20th anniversary commemorations of the programme. On 23 February, the broadcast put out a casting call for contestants who would appear on the game show.[20] On 9 March, Jeremy Clarkson was confirmed as the new host of the show.[21] On 13 April, the trailer for the revival premiered on ITV and confirmed that the show would return in May for a week-long run.[22] Shows aired from 5 May to 11 May and were filmed in Studio HQ2 at dock10 studios in Greater Manchester. The first episode drew an average of 5.06 million viewers, a 29.7% TV share.[23]

ITV renewed the show for another series, with Clarkson returning as host. It aired for 6 episodes from 1 to 6 January 2019.[24] The second half of the second series began on 4 March 2019 with 5 episodes. The third series began on 24 August 2019 with 11 episodes with the episodes airing like the old format once weekly.

ITV then renewed a fourth series for a celebrity edition of the show, with Clarkson returning as host and showing 4 episodes airing on 25 December 2019, (a Christmas Special), 4 January 2020, 5 January and 12 April.[25][26][27][28]

Top prize winners

Over the course of the programme's broadcast history, it has had five winners who received its top prize of £1 million. They are:

- Judith Keppel,[29] a former garden designer. On 20 November 2000, she became the first contestant to win the top prize. Following her success, Keppel later went onto become part of team of quiz experts for the BBC game show, Eggheads.

- David Edwards, a former physics teacher of Cheadle High School and Denstone College in Staffordshire. On 21 April 2001, he became the second contestant to win the top prize. Following his success, Edwards went on to compete in both series of Are You an Egghead?, in 2008 and 2009 respectively, but failed to win either series and secure a place as a panellist on Eggheads.

- Robert Brydges,[30] an Oxford-educated banker from Holland Park, London.[31] On 29 September 2001, he became the third person to win the show's top prize.[32][33]

- Pat Gibson, a multiple world champion Irish quiz player. On 24 April 2004, he became the fourth person to win the top prize.

- Ingram Wilcox, a British quiz enthusiast. On 23 September 2006, he became the fifth person to win the top prize.

Format

Auditioning

During the original run, members of the public who wished to apply for the game show were provided with four options to choose from – calling/texting a premium-rate number; submitting an application via the show's ITV website, using a system of £1 ‘credits’, or taking part in a casting audition, which were held at various locations around the UK. Once an application was made, production staff selected an episode's contestants through a combination of random selection, and a potential contestant's ability to answer a set of test questions based on general knowledge.

Game rules

| Payout structure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question number |

Question value | |||||

| 1998–2007 | 2007–2014 | 2018– present | ||||

| 15 | £1,000,000 | |||||

| 14 | £500,000 | £500,000 | ||||

| 13 | £250,000 | £250,000 | ||||

| 12 | £125,000 | £150,000 | £125,000 | |||

| 11 | £64,000 | £75,000 | £64,000 | |||

| 10 | £32,000 | £50,000 | £32,000 | |||

| 9 | £16,000 | £20,000 | £16,000 | |||

| 8 | £8,000 | £10,000 | £8,000 | |||

| 7 | £4,000 | £5,000 | £4,000 | |||

| 6 | £2,000 | £2,000 | ||||

| 5 | £1,000 | |||||

| 4 | £500 | |||||

| 3 | £300 | N/A | £300 | |||

| 2 | £200 | £200 | ||||

| 1 | £100 | £100 | ||||

| ||||||

Once contestants auditioned for a part on the programme and filming took place, they undertook a preliminary round entitled "Fastest Finger First". Initially, the round required contestants to provide the correct answer to a question, but from series 2 onwards, they were tasked with putting four answers in the correct order stated within the question (i.e. earliest to latest). The contestant who answered the question correctly, and in the fastest time, won the opportunity to play the main game. In the event that no one answered the question correctly, a new question was asked, while if two or more contestants gave the correct answer in the same time, there was a tiebreaker question to determine who proceeded to the main game. The round was primarily used to determine the next contestant for the main game, and was more often than not used more than once in an episode.

Upon completion of the preliminary round, the contestant began the main game, tackling a series of increasingly difficult questions, which offered progressively higher sums of money, up to the top prize of £1,000,000. The stacks of 15 questions were randomly chosen from a list of pre generated questions based on general knowledge. For each question there were four options to choose from, labelled ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’. During the game, contestants were allowed to use a set of 3 lifelines to help them with a question at any time, and two monetary safety nets were provided: if a contestant got a question wrong, but had reached a designated cash value during their game, they left with that amount as their prize. If a contestant was unsure about a question they were facing, they were allowed to leave the game at that point with the cash amount they had already won. While the initial questions were typically generally easy, the subsequent ones after it required the contestant to confirm that their answer/decision is final, at which point it became locked in and could not be reversed. As a rule, host Tarrant was not shown the correct answer on his monitor until a contestant had given their final answer. If an episode had reached the end of its allotted time, an audio cue was triggered to highlight this; contestants who were still playing the main game were left to wait until filming for the next episode began before they could continue, though this was not the case for special editions of the show, such as celebrity episodes.

Over the course of the show's history on British television, the format of the programme has been altered in a number of aspects, mainly towards the setup of questions and the payout structure used in the game show, along with minor tweaks and changes in other aspects:

- Between September 1998 and July 2007, contestants had to answer 15 questions, with two safety nets placed at £1,000 and £32,000, and they were allowed three standard lifelines.

- Between August 2007 and February 2014, the number of questions was reduced to 12, with most cash values adjusted. This alteration led to the second safety net being assigned to £50,000.

- From the start of the 27th series in August 2010, the format was changed to include a clock format, similar to the 2008–10 US version, but with some differences. The time limit was 15 seconds for the first two questions, and 30 seconds for the next five questions, but the last five questions had no time limit. The clock would start ticking down as soon as the answers appeared on screen, and the contestant would have to give his/her final answer within the time limit. If they ran out of time it was treated as an incorrect answer. The clock would briefly pause, however, if any lifeline was used. It also added a new, fourth lifeline, Switch, which would be made available after passing question seven. The first episode of this series also saw the discontinuation of 'Fastest Finger First' for the first time since the inception of the show, so the contestants were then pre-selected by the production staff.

- For the revival in 2018 and subsequent series of the show, the show returned to the 1998–2007 format, including the original payout structure and fastest finger process, with minor differences. A new lifeline, ‘Ask The Host’, was introduced and the placement of the second safety net could be set by the contestant. Upon reaching £1,000, the contestant would be asked before each subsequent question if they would like to set the safety net to the cash value, with it offered up to question 14, £500,000. The number of contestants for 'Fastest Finger First' were also reduced from ten to six.

- At the end of the allotted time of each standard episode, a loud sound (one long brass note) indicates the end of the show. The host refers to this noise as the ‘klaxon’. During the live specials whilst Tarrant was host, the contestant's game would end and any question in play would be null and void unless they gave a final answer before the klaxon sounded. The contestant’s game then carries on at the start of the next episode.

Lifelines

During a contestant's game, they may make use of a set of lifelines to assist them on a question. Each lifeline may only be used once. Throughout the course of the show's history, these lifelines involve the following:

- 50/50: (1998–present): Two random incorrect answers are eliminated by the computer, leaving the correct answer and the one remaining incorrect answer, thus granting the contestant a 50/50 chance of answering the question correctly.

- Phone a Friend: (1998–present): The contestant calls one of their friends, and has 30 seconds to read the question and answers to them. The friend uses the leftover time to offer an answer. Since 2011, a member of the production team accompanies the friend to prevent cheating, such as using the Internet or reading books, and is verified by the presenter before the contestant can confer.

- Ask the Audience: (1998–present): Audience members use keypads to vote on what they believe to be the correct answer to the question they’ve been asked. The percentage of each option selected by the audience is displayed to the contestant and audience after this vote.

- Switch/Flip (2002–03, 2010–14): The computer replaces one question with another of the same monetary value. Any lifelines already used on the original question are not reinstated. In its original run, Switch was originally called "Flip" and could only be used if the contestant traded an unused lifeline for it, using it up to three times. From 2010 to 2014, this lifeline was separated and became available after the contestant answered seven questions correctly.

- Ask the Host (2018–present): The presenter offers advice or an answer to the question they are asked. The host usually discloses that he has no contact with outside sources, and there is no time limit as to how long he can offer help. The question's answer is not revealed to the host when this lifeline is used; instead, the computer reveals the answer to the host and contestant at the same time.[34]

Series overview

Main series

| Series | Start date | End date | Episodes | Presenter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 September 1998 | 25 December 1998 | 11 | Chris Tarrant |

| 2 | 1 January 1999 | 13 January 1999 | 13 | |

| 3 | 5 March 1999 | 16 March 1999 | 12 | |

| 4 | 3 September 1999 | 14 September 1999 | 13 | |

| 5 | 5 November 1999 | 25 December 1999 | 18 | |

| 6 | 16 January 2000 | 22 January 2000 | 7 | |

| 7 | 26 March 2000 | 1 May 2000 | 13 | |

| 8 | 7 September 2000 | 6 January 2001 | 55 | |

| 9 | 8 January 2001 | 26 April 2001 | 45 | |

| 10 | 4 September 2001 | 29 December 2001 | 43 | |

| 11 | 5 January 2002 | 9 April 2002 | 55 | |

| 12 | 31 August 2002 | 28 December 2002 | 20 | |

| 13 | 4 January 2003 | 31 May 2003 | 22 | |

| 14 | 30 August 2003 | 27 December 2003 | 22 | |

| 15 | 3 January 2004 | 5 June 2004 | 23 | |

| 16 | 18 September 2004 | 25 December 2004 | 16 | |

| 17 | 1 January 2005 | 11 June 2005 | 25 | |

| 18 | 17 September 2005 | 31 December 2005 | 10 | |

| 19 | 7 January 2006 | 8 July 2006 | 28 | |

| 20 | 9 September 2006 | 6 January 2007 | 13 | |

| 21 | 10 March 2007 | 28 July 2007 | 18 | |

| 22 | 18 August 2007 | 30 October 2007 | 10 | |

| 23 | 1 January 2008 | 3 June 2008 | 20 | |

| 24 | 16 August 2008 | 31 January 2009 | 18 | |

| 25 | 13 June 2009 | 20 December 2009 | 20 | |

| 26 | 13 April 2010 | 8 June 2010 | 8 | |

| 27 | 3 August 2010 | 23 December 2010 | 10 | |

| 28 | 2 April 2011 | 19 December 2011 | 6 | |

| 29 | 3 January 2012 | 20 December 2012 | 10 | |

| 30 | 1 January 2013 | 11 February 2014 | 10 | |

| 31 | 5 May 2018 | 11 May 2018 | 6 | Jeremy Clarkson |

| 32 | 1 January 2019 | 6 January 2019 | 10 | |

| 4 March 2019 | 8 March 2019 | |||

| 33 | 24 August 2019 | 20 October 2019 | 10 | |

| 34 | 25 December 2019 | 12 April 2020 | 10 | |

| 10 May 2020 | 15 May 2020 | |||

| 35 |

Specials

- Is that Your Final Answer? – a one-hour documentary about the show, which aired on ITV on 24 December 1999.[35][36] Directed and produced by Robin Lough, it featured rare footage from the unaired pilot version of the programme, which has completely different music and behind the scenes footage from the programmes aired in Series 4 (September 1999). A similar documentary of the same name was also aired in Australia during 2000. A shorter half-hour Russian version was aired on 4 November 2000. Both of these primarily concentrated on their own versions of the show and featured the local hosts.

- Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Night – a two-and-a-half-hour long special, which included parts of Is that Your Final Answer?, that aired on digital channel ITV2 in 2000. Hosted by Tarrant, it looked back on the first two years of the UK version, showing some of its best moments. It also looked at the original U.S. and Australian versions.

- Who Wants to be a Millionaire?: Major Fraud – A special episode of Tonight which focused on the 2001 cheating scandal, hosted by Martin Bashir. It featured key segments of Charles Ingram's run as well as interviews by the witnesses of the ensuing trial, such as fellow contestants and members of the production crew. It was broadcast in the UK on 21 April 2003 (before airing in the US on 8 May 2003 as a special episode of ABC's Primetime). An additional 2 hour documentary on the scandal entitled Who Wants to Steal a Million? was also shown in the US, which featured Ingram's full unedited run.[37]

- Quiz – A drama in three parts, each one hour in length, which aired on 13, 14 and 15 April 2020 and is based James Graham's play of the same name which centres on the 2001 'cheating scandal'.

Text game (2004–2007)

On 23 October 2004 the show included a new feature called the "Walkaway Text Game". The competition was offered to viewers at home to play the text game where they had to answer the question, if a contestant decided to walk home with the cash prize they have got, by choosing the letters 'A, B, C or D' within 30 seconds to a specific mobile number. The viewer who answered the question won £1,000 by having their entries selected randomly.

On 9 September 2006, there were some changes. The competition stayed the same but this time, they played it before some commercial breaks. A question to which the contestant had given their final answer, but the correct answer had not yet been revealed, was offered as a competition to viewers. Entry was via SMS text message at a cost of £1 per entry, and the competition ran through the commercial break, after which the answer was revealed and the game continued. One viewer who answered the question correctly won £1,000. The text game ended on 28 July 2007.[38]

Controversies

Incorrect answer to question accepted

On 8 March 1999, contestant Tony Kennedy reached the £64,000 question. He was asked "Theoretically, what is the minimum number of strokes with which a tennis player can win a set?", and given four possible answers – twelve, twenty-four, thirty-six, and forty-eight. Kennedy, who calculated that a player would need four shots to win a game, with six games in a set, answered twenty-four, and was told the answer was correct.[39][40]

However, the right answer was actually twelve and viewers quickly phoned up the show to complain.[39] One such viewer, Robert Steadman, explained to The Irish Times:

- "A tennis player needs six games to win a set. Let's assume he serves aces for his three service games – four shots for three games which equals 12 strokes. Now, if his opponent double faults all their serves – so losing love 40 – the player hasn't had to make any strokes."[41]

The production staff acknowledged the mistake and apologised for it, but allowed Kennedy to keep his prize money (an eventual £125,000).[39]

Schedule rigging allegation

When Judith Keppel's victory as the first UK jackpot winner on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? was announced by ITV on the day of that the corresponding episode was to be broadcast, several allegations were made that Celador had rigged the show to spoil the BBC's expected high ratings for the finale of One Foot in the Grave.[42] Richard Wilson, the lead star on the sitcom, was quoted in particular for saying that the broadcaster had "planned" the win, adding "it seems a bit unfair to take the audience away from Victor's last moments on earth."[43] David Renwick, writer of the sitcom, voiced annoyance that the episode would draw away interest from the sitcom's finale, believing that a leaked press release on ITV's announcement had been "naked opportunism", and it "would have been more honourable to let the show go out in the normal way", pointing out that it "killed off any element of tension or surprise in their own programme", but that "television is all about ratings".[42] Richard Webber's account, in his 2006 book, cites "unnamed BBC sources" as those who "questioned the authenticity of Keppel's victory".[42] The allegations, in turn, led to eleven viewers making complaints against the quiz show, of a similar nature, to the Independent Television Commission (ITC).[44]

In response, ITV expressed distress at the allegations, claiming that it "undermined viewers' faith in the programme." Leslie Hill, the chairman of ITV, wrote to Sir Christopher Bland, the chairman of the Board of Governors of the BBC, to complain about the issue. The corporation apologised, saying that any suggestion of 'rigging' "did not represent the official view of the BBC",[45] while the ITC's investigation cleared the programme of any wrongdoing.[44][46][47]

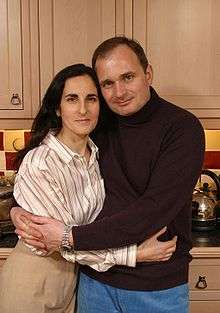

Ambiguous question

On 11 February 2006, celebrity couple Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen and his wife Jackie took on the game show to raise money for their chosen charity – The Shooting Star Children's Hospice. Having reached the final question of the quiz, they were asked "Translated from the Latin, what is the motto of the United States?", to which the Bowens answered with "In God We Trust", only to learn that the question's correct answer was "One Out of Many" – the English translation for the Latin E pluribus unum.[48] However, Celador later admitted that the question had been ambiguous and not fair to the pair – although E pluribus unum is considered the de facto motto of the United States, it was never legally declared as such; In God We Trust is the official motto of the country since 1956, although it is not translated from any form of Latin. Following this revelation, the production company invited the Bowens back to tackle a new question, with their original winnings reinstated; the couple chose not to risk the new question, and left with £500,000 for their charity.[48]

Ingram cheating scandal

In September 2001, British Army Major Charles Ingram became a contestant on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, alongside college lecturer Tecwen Whittock and with Ingram's wife Diana in the audience. After the first day of filming, the group devised a scheme that would allow Ingram to win the £1 million cash prize when he returned for the second day of recording, on 10 September – for each question he faced, the correct answer would be signalled to Ingram by a cough made by Whittock;[49] Ingram would differentiate the way he received this to avoid making the scheme too obvious, such as reading aloud all four answers, or dismissing an answer and then choosing it again later.[49] Although the scheme proved successful, by the time he had reached the final questions, production staff off-stage had become suspicious over the amount of background noise being made by Whittock's coughing,[50] while noting that Ingram seemed to show no specialist knowledge of any subjects he faced with each question.

After the second day of recording ended, the production staff ordered an immediate investigation on the grounds that cheating had occurred, suspending the broadcast of both episodes that had been filmed. Ingram was subsequently informed that he was being investigated for cheating and would not receive his winnings. While reviewing the recording, production staff began to see a pattern between Whittock's coughing, and Ingram's unusual behaviour when he answered questions;[51][52] at one point, they noticed Ingram gave an answer when Diana had coughed after he read it aloud. By this point, production company Celador was convinced that cheating had occurred, and the matter was handed over to police. Both the Ingrams and Whittock were charged with "procuring the execution of a valuable security by deception", and taken to Southwark Crown Court in 2003.

During the four-week long trial, the Prosecution provided evidence towards the charges, which included a recording of Ingram's second day on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, pager telephone records for a previous scheme the group intended to use,[53] before deeming it too complicated – a system of four pagers intended to be hidden on Ingram's body, in which a pager's vibrations signalled the correct answer – and testimony from one of the production staff and a "Fastest Finger" contestant attending the recording, Larry Whitehurst.[50][54] Although the Defence provided evidence claiming Whittock's coughing was a result of dust allergies and a hay fever he was suffering from, and Whittock himself testified against the accusations,[50][55] the Prosecution refuted these claims with their evidence, including footage that showed Whittock stopped coughing when he became a contestant after Ingram.[53] On 7 April 2003, the group were found guilty, with all three given suspended prison sentences and fines, with the Ingrams later ordered to pay legal costs within two months of the trial's conclusion.[50] On 24 July 2003, the British Army ordered Charles Ingram to resign his commission as a Major, in the wake of the trial.[56]

In the aftermath of the trial, the scandal became the subject of an ITV documentary entitled Millionaire: A Major Fraud (aired as an edition of Tonight with Trevor McDonald) presented by Martin Bashir and broadcast on 21 April 2003, with a follow-up two weeks later entitled Millionaire: The Final Answer.[57] The documentary featured excerpts from the recording that had been enhanced for the Ingrams' trial, footage of the actions made by Ingram's wife in the audience, and interviews with production staff and some of the contestants who had been present during the recording. None of the defendants in the case took part, with Ingram later describing Major Fraud and a subsequent programme of the matter, shown on ITV2, as "one of the greatest TV editing con tricks in history". Chess grandmaster James Plaskett later wrote an essay arguing in favour of the group's innocence;[58] journalists Bob Woffinden, and Jon Ronson,[59] each wrote a piece influenced by this essay, with Woffinden collaborating with Plaskett on a book entitled Bad Show: The Quiz, The Cough, The Millionaire Major, published in 2015, arguing that Ingram's appearance on the show coinciding with Whittock's was "chance".[60] A play based upon the events of the scandal was written by James Graham, entitled Quiz, and was performed from 3 November 2017 to 9 December 2017,[61] before being performed in the West End from 31 March 2018 to 16 June 2018.[62] Following the success of the play's West End run, ITV commissioned a three-part adaptation of the same name starring Matthew Macfadyen and Sian Clifford as the Ingrams, which aired over three nights between April 13–15, 2020.[63]

The Syndicate

The Phone-a-Friend lifeline provided multiple instances of controversy during the show's run. In March 2007 various UK newspapers reported that an organised syndicate had been getting quiz enthusiasts onto the show in return for a percentage of their winnings. The person behind the syndicate was Keith Burgess from Northern Ireland. Burgess admitted to helping around 200 contestants to appear on the show since 1999; he estimates those contestants to have won around £5,000,000. The show producers are believed to have been aware of this operation, with Burgess stating: "The show knows about me and these types of syndicates, but they cover it up to keep the show going."[64][65]

An earlier version of a Phone a Friend syndicate was reported in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo during 2003.[66] Paul Smith, the managing director of Celador Productions, stated: "We are aware of Paddy Spooner and what people similar to him are doing, and we have made a priority of changing our question procedure. We are confident we have now made it impossible for anyone to manipulate the system."[66] Since then, the options of people that can be called have a picture of themselves shown on-air. During the 2010–14 era and with the show's relaunch in 2018, every person listed as a friend who might be called had a person from the production company present to video their actions.

In April 2020 the Daily Mirror provided more up-to-date details on how the syndicate run by Keith Burgess and Paddy Spooner had operated. Burgess admitted to getting five people on to the show within one hour.[67]

Filming locations

Since airing in September 1998, Who Wants To Be A Millionaire has been filmed at 3 locations throughout its 21-year run. It was first filmed at the now-defunct Fountain Studios in London from its inception until the end of the third series which aired in March 1999. It then moved to Elstree Studios in nearby Hertfordshire, in preparation for series 4, which aired in September 1999. Elstree was then home of Millionaire until the end of its initial run in February 2014. For the show’s revival in 2018 and all subsequent episodes, filming moved to dock10 studios in Salford.

- Fountain Studios – Series 1–3 (36 episodes)

- Elstree Studios – Series 4–30 (556 episodes)

- dock10 studios – Series 31–present (38 episodes)

References

Footnotes

- "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire". Gameshow Hall of Fame. GSN. 21 January 2007.

- "Millionaire". Andy Walmsley, Production Designer. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Smurthwaite, Nick (21 March 2005). "Million Pound Notes: Keith Strachan". The Stage. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- Deans, Jason (29 November 2001). "Millionaire ratings slide" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Millionaire: A TV phenomenon". BBC News. 3 March 2003. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Cozens, Claire (26 January 2004). "TV ratings: January 23–24" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Day, Julia (3 May 2005). "TV ratings: April 30" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Holmwood, Leigh (23 January 2008). "TV ratings – January 22: Ladettes fail to attract viewers to ITV" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Plunkett, John (1 September 2010). "The Bill finale wins 4.4m viewers | TV ratings – 31 August" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Leonard, John J. (2005). "Millionaire 2nd Edition.qxd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- Dasey, Daniel (30 March 2003). "The show that should have made me a million". The Sydney Sun-Herald.

- Birmingham Sunday Mercury, 28 August 2005

- Loveday, Samantha (1 December 2006). "New owners take on Celador International and Millionaire brand". toynews-online.biz. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- Levine, Stuart (4 June 2008). "Sony Pictures acquires 2waytraffic". Variety. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- Plunkett, John (12 January 2011). "ITV looks to revive Millionaire's sparkle" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "This summer, Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? will once again be going live, but this time with the Great British public in the hotseat!". ITV. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire axed as host Chris Tarrant decided 'it was time to take a break'". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "Millionaire axed as Tarrant quits". u.tv. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Jones, Ellen (12 February 2014). "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Chris's Final Answer – TV review: 'Tarrant isn't quite on the money'". The Independent. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?". itv.com. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "Jeremy Clarkson replaces Chris Tarrant on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?". BBC News. 9 March 2018.

- Lee, Ben (13 April 2018). "ITV releases trailer for Jeremy Clarkson's Who Wants to Be a Millionaire revival". Digital Spy. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- O'Connor, Rory (7 May 2018). "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire: Jeremy Clarkson and Chris Tarrant's ratings war REVEALED". Express.co.uk.

- "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? returns to ITV in 2019". www.ITV.com. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Celebrity Special Episode 1". Press Centre. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Celebrity Special Episode 2". Press Centre. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Celebrity Special Episode 3". Press Centre. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Celebrity Special Episode 1". Press Centre. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Charles Mosley (ed.), Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage (London: Burke's Peerage, 1999)

- "Fourth Millionaire 'is millionaire'". BBC. 29 September 2001. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "'Millionaire' quiz show aims to broaden appeal". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Fourth contestant wins 'Millionaire'". Digital Spy. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "So I phoned a friend – part one". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? returns to ITV this Saturday with brand new twists".

- "ITV 1999". UK Christmas TV. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Coldclough. "Who Wants To Be A Millionaire – Is That Your Final Answer Documentary (1999)". Retrieved 5 January 2019 – via YouTube.

- "Who Wants to Steal a Million?". IMDb. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Millionaire—Walkaway Game". itv.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- "Quiz 'winner' keeps his prize". BBC News. 9 March 1999. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- James Booker. "Who Wants to be a Millionaire? 8th March 1999 Tony Kennedy" – via YouTube.

- "Man scores with wrong answer". The Irish Times. 9 March 1999. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Webber 2006, p. 184

- "Wilson: Millionaire win 'planned'". BBC News. 22 November 2000. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "Millionaire? cleared of ratings 'fix'". BBC News. 15 January 2001. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- Judd, Terri (2 December 2000). "BBC apologises for 'Millionaire' dirty tricks slur". The Independent. London.

- Casey & Calvert 2008, p. 128

- Dyja 2002, p. 20

- "TV designer's second shot at £1m". British Broadcasting Corporation. 13 January 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "Major Charles Ingram has been found guilty of cheating his way to the top prize on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire". BBC News. 7 April 2003. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- "Millionaire trio escape jail". BBC News. 8 April 2003. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Millionaire's route to the top prize". 7 April 2003. Retrieved 5 January 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Millionaire cheats left 'devastated'". 21 April 2003. Retrieved 5 January 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Innes, John (7 March 2003). "Pager plot too risky for TV quiz". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- "Contestant 'spotted Millionaire coughs'". BBC News. 11 March 2003. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "So I phoned a friend – part two". The Guardian. London. 19 April 2003. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- "Millionaire cheat sacked by Army". 24 July 2003. Retrieved 5 January 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Day, Julian (22 April 2003). "The cough carries it off". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Millionaire Three – The Rich, The Poor And Inbetween". Archived from the original on 22 August 2012.

- Ronson, Jon (17 July 2006). "Are the Millionaire three innocent?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- Winchester, Levi (17 January 2015). "'Coughing Major' was INNOCENT of cheating on Who Wants to be a Millionaire, says new book". Daily Express. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "Quiz". Chichester Festival Theatre. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Quiz the Play by James Graham | Official West End Website". 12 April 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "ITV has commissioned 'Quiz' directed by Stephen Frears starring Hollywood star, Michael Sheen". ITV Media. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Phoney a Friend". Sunday Mirror. 18 March 2007.

- "Quiz syndicate leader denies wrongdoing". crewechronicle.co.uk. 23 March 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Millionaire syndicate is probed". northamptonchron.co.uk. 23 April 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Waddell, Lily (10 April 2020). "Millionaire cheats conned show out of £5m in bigger scam than Charles Ingram". mirror.

Bibliography

- Casey, Bernadette; Calvert, Ben (2008). Television Studies: The Key Concepts (2 ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-37149-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dyja, Eddie, ed. (2002). BFI Film and Television Handbook 2002. London: British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-904-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webber, Richard (2006). The Complete One Foot in the Grave. London: Orion. ISBN 978-0-7528-7357-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woffinden, Bob; Plaskett, James (2015). Bad Show: The Quiz, the Cough, the Millionaire Major. Bojangles Books. ISBN 978-0-9930755-2-0.