Whaling in the Faroe Islands

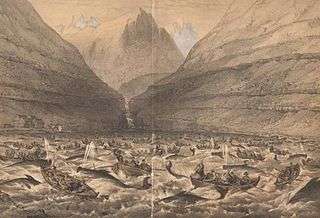

The Grindadràp (means slaughter in feroian) beaching and slaughtering long-finned pilot whales, a type of dolphin drive hunting, has been practiced in the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic since about the time of the first Norsemen settled there which is approximately the 9th Century. The hunters first surround the pilot whales with a wide semicircle of boats. Then the boats drive the pilot whales into a bay or to the bottom of a fjord. Not all bays are certified, and the slaughter will only take place on a certified beach. Many Faroese consider the whale meat an important part of their food culture and history. Animal rights groups criticize the slaughter as being cruel and unnecessary.[1][2][3]

Whaling is considered an example of aboriginal whaling, which is the only one in Western Europe nowadays. We can see marine hunts in Egadi Islands in Sicily with tuna, or in Japan. Whaling was mentioned in the Sheep Letter, a royal Decree made by Duke Haakon, a Faroese law from 1298, as a supplement to the Norwegian Gulating law.[4]

Currently whaling is regulated by the Faroese authorities, which is represented by the Home Rule Government since 1948.[5] Around 800 long-finned pilot whales[6] and some Atlantic white-sided dolphins[7] are slaughtered annually, during the summer season. The hunts, called Grindadráp in Faroese, are non-commercial and are organized on a community level between the 17 islands of the archipelago. The police and Grindaformenn (chief of the grind during the hunt)are allowed to remove people from the grind area.[5]

Facing criticism and activism repeat offenses towards this practice, the grind had to change a bit compared to its original rituals. Now, those who participate in the killing must have a special training certificate on slaughtering a pilot whale with the spinal-cord lance.[8] The Grind law was updated in 2015, where one of the regulations demanded that the whalers followed a course on how to slaughter a pilot whale with the spinal-cord lance.[9] These protests recently raised put the grind in a maritime security debate. Maritime security can be linked to Faroe Islands, since marine environment, and economical development such as blue economy are important topics that surrounds Grindadràp since 1980s (date of the first protests).

In November 2008, Høgni Debes Joensen, chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands and Pál Weihe, scientist, recommended in a letter to the Home Rule Government that pilot whales should no longer be considered healthy for human consumption because of the high level of mercury, PCB and DDT derivatives.[10][11] However, the Faroese government did not forbid whaling, considering tradition and marine cultural heritage is still very important. From 2002 to 2009 the PCB concentration in whale meat has fallen by 75%, DDT values in the same time period have fallen by 70% and mercury levels have also fallen.[12] For example, Weihe explained in an article [13] that a 1977 study and most recent ones, showed the impact that could have the consumption of pilot whales on nervous system foetal development. The too high rate of mercury contained in the meat is dangerous for the good development of the foetus during pregnancy.

This article is taking a constructivist point of view, in Maritime Security, which broader the concepts to all the actors implicated in marine life, all economic perspectives and look also at the practice theory, inspired by Christian Bueger new approach of Maritime Security in International relations.[14]

Historical background

Archaeological evidence from the early Norsemen settlement of the Faroe Islands c. 1200 years ago, in the form of pilot whale bones found in household remains in Gøta on Eysturoy, indicates that the pilot whale has long had a central place in the everyday life of Faroe Islanders. This practice was a good way to gather and share food, which was socially crucial for the islanders. In 1298, a legal document explaining who has rights on whales, and the driven and stranded ones were kept in national records as the first one ever written in the country. Catches records from 1584 are also kept in archives and it is continuing since. The grind is a community tradition, where the meat is shared between the locals. It was initially followed by a traditional dance (gridadansur), and this hunt was a good way to reunite the inhabitants of the community. There is still today paintings and cultural arts, depicting the grind as an important symbol of cultural identity. The meat and blubber of the pilot whale have been an important part of the islanders' staple diet. The islanders have particularly valued blubber: both as food and for processing into oil, which they used for lighting fuel and other purposes like medicine. The blubber of the bottlenose whale is not fit for food, as it gives diarrhea.[15] In older days, it was used for medicinal purposes. People also used parts of the skin of pilot whales for ropes and lines, while utilising the stomachs as fishing floats. The economical and cultural importance of such marine tradition has a special place in faroese people, and constitute a marine cultural heritage, that shaped an entire social and cultural community. Faroese are coastal people, surrounded by a big marine biodiversity. The article of Arge V. Simùn and it colleagues</ref> Símun V. Arge, Guðrún Sveinbjarnardóttir, Kevin J. Edwards and Paul C. Buckland,”Viking and Medieval Settlement in the Faroes: People, Place and Environment”, Human Ecology, Vol. 33, No. 5, Historical Human Ecology of the Faroe Islands, pp. 597–620, 10/2005</ref>, on the settlement and economic activity on faroese tells us that the marine environment was a big part of the faroese life, and built their economic activity and their way of living during the years. This is why we can assume that the faroese traditions related to marine activities are traditionally ancred in their historical patrimony. This ancient tradition permitted citizens to survive during the winter time, because they were able to freeze meat for the whole year. This was a survival practice at first, which was the main way to feed during the Middle Age.

“We can observe a ‘heritage boom’ that is part of ‘an international preoccupation with reclaiming, preserving and reconstituting the past’ and a national and local ‘quest for defining identity”[16]

Laws have regulated rights in the Faroes since medieval times, about 800 A.C. References appear in early Norwegian legal documents, while the oldest existing legal document with specific reference to the Faroes, the Sheep Letter from 1298, includes rules for rights to, and shares of, both stranded whales as well as whales driven ashore.[17] The Danish government defers all decision on whaling policy to the Faroese government since 1832.

The traditional hunting process and its evolution

There are no fixed hunting seasons, but the grind is likely to happen during spring and summer periods, from June to October. As soon as a pod close enough to land is spotted, the locals set out to begin the hunt, after approval from the sysselman. The animals are driven into a bay which is approved for whaling by the Faroese government, and then they try to make the whales to beach themselves. The only way out is being blocked off by some of the boats, which stay there until men who have been waiting on shore have slaughtered all the whales.[18]

The sighting

The pilot whale hunt has a well-developed system of communication. Reverend Lucas Debes made reference to the system, which means that it had already developed by the seventeenth century, but the statistics go back to 1584.[19] Historically the system took place in this way: when a school of pilot whales had been sighted near land, messengers were sent to spread the news among the inhabitants of the island involved (the Faroes have 17 inhabited islands). At the same time, a bonfire was lit at a specific location, to inform those on the neighbouring island, where the same pattern then was followed.In comparison to Faroe Islands, Margaret Lantis made a big study on whaling cultures in 1938, which aimed to describe the different whaling traditions she could observe in North Canada in small tribes. She says for example " The whaling season at Pt Barrow lasted approximately from April 1st to June 1st. "During the months the whaling lasted, all the men lived uninterruptedly out at the edge of the ice, despite much inconvenience arising from the tabu system.Tents were forbidden, and they had therefore to be content with storm shelters made of skins, or seek some protection from the elements under the boat. It was also forbidden to dry clothes, and raw food was tabu; all meat had to be boiled".[20] This quote refers to an Indian tribes in American Arctic. For instance, the first 14 points relates to the honor/power given to the whalers and to their secret knowledge, as a caste system where the number of whalers were very limited (n°1) for example. There could be (cultual, not societal) initiation to young whalers (n°3) as a ritual to learn the sacred practices and secrets of the hunt. At this point of the text she tries to gather all the knowledge she found on the tribes and warns us about the many gaps she encountered in her research. Esoterism is a crucial concept to understand the whaling hunt because the spiritual and sectarian aspects are intertwined into a singular practice. The whaling hunt represent a big part of the tribe society, as a social norm. She asks herself if the dangerous aspect of the hunt was the reason why it was naturally ritualized.

It is believed that the system is one of the oldest elements concerning the pilot whale hunt. This is because a rather large number of boats and people are necessary to drive and kill a school of pilot whales, depending on the number of whales. Today the news of a sighting is relayed by phone, and radios on sophisticated motorboats and other modern methods of communication.

Locations

The location must be well-suited to the purpose of beaching whales. This is what Russell Fielding[21] calls "coastal geomorphology", which is the study of the strong relationship between the man and its physical environment, in a cultural and historical way. It says that cultural system and activities, have been determined by some physical aspects of the local environment.

Using coastal survey methods, Fielding shows a lack of strong correlation between beaches morphology and the practice/regulation of whaling nowadays. Indeed, the coastal geomorphology of the spaces are the cause of some law and practices as far as the whales drives are concerned. For example, driving whales in the beaches which have not been declared as approved, is strictly forbidden. There's 22 approved whaling drives areas (hvalvàgir), on 7 out of 17 islands. This list is being updated periodically where bays have naturally been changing through time. But the authorised bays are often the ones where traditionally the whaling occurred, even before the appearance of the Home Rule government. A typical whaling bay must be in a certain shape and is even better without the presence of a marbakki (sharp and sudden shelving close to inshore). The marbakki is a really special place, marked by many symbols in the history and culture in Faroe Islands.

Fielding also used a multifaceted analysis to determine if social and political influences occurred with the grind. As a result, we can see that some beaches were the scene of most of the grind whereas some have never been. The marbakki might be affecting the determination of whaling bay effectiveness. 15 out of 17 approved beaches did not have any marbakki. “A marbakki may render a beach wholly unsuitable, but it seems that social and historical factors can influence the continued inclusion of even an otherwise poorly-suited beach on the government's approval list, as is discussed below.” The marbakki is a kind of disqualifier, and beach slopes might be a qualifier to be a whaling beach in Faroe Islands. Therefore, we can see the complex interdependent relationship between societies and physical environment where the control and regulation of whaling is interlinked with the space.

It is against the law to kill pilot whales at locations with inappropriate conditions. Given such conditions, the chances are good that the whales can be driven fully ashore or close enough to the shore that they can be killed from land. When a school of pilot whales is sighted, boats gather behind them and slowly drive them towards the chosen authorized location, usually a bay or the end of a fjord. There are 23 towns, villages or bays (Viðvík is not populated) that have the right conditions, and therefore legal authorization, for beaching whales. These are in alphabetical order: Bøur, Fámjin, Fuglafjørður, Húsavík, Hvalba (and Nes-Hvalba), Hvalvík, Hvannasund, Klaksvík, Leynar, Miðvágur, Norðragøta, Norðskáli, Sandur, Syðrugøta, Tjørnuvík, Tórshavn (in Sandagerð), Tvøroyri, Vágur, Vestmanna, Viðvík (near Hvannasund, but on the east coast of Viðoy) and Øravík.[22]

These towns and villages have featured most heavily in the statistics for whaling in the Faroes from 1584 to 2000:

From 1584 until 1641 the statistics are not complete, and in the Gabel's periods from 1642–1708 only a few statistics are available, but from 1709 until today the statics seem to be concise and reliable. Statistics before 1584 were the responsibility of the Catholic church and are not available in the Faroes today. But statistics back to as far as 1584 are available.[23]

- Miðvágur (Vágar) with 269 grinds (pods of pilot whales) (14,9%) and 46,737 whales (18,5%), in the periods 1749–1775 and 1783–1791 no whales were slaughtered there

- Klaksvík (Borðoy) with 233 grinds (12,9%) and 37,964 whales (15,1%), in the periods 1753–1770 and 1771–1793 no whales were slaughtered there

- Hvalvík (Streymoy) 193 grinds (10,7%) and 31,562 whales (12,5%), in the periods 1755–1780 and 1782–1796 no whales were slaughtered there

- Vágur (Suðuroy) with 155 grinds (8,6%) and 21,144 whales (8,4%), in the periods 1742–1795 and 1926–1935 no whales were slaughtered there

- Vestmanna (Streymoy) with 141 grinds (7,8%) and 19,695 whales (7,8%), in the periods 1732–1801 and 1820–1830 no whales were slaughtered there

- Hvalba (Suðuroy) with 136 grinds (7,5%) and 17,664 whales (7,0%), in the periods 1748–1792 and 1921–1931 no whales were slaughtered there

- Tórshavn (Streymoy) with 107 grinds (5,9%) and 13,678 whales (5,4%) in the periods 1728–1821 and 1897–1929 no whales were slaughtered there

- Hvannasund (Viðoy) with 83 grinds (4,6%) and 8,441 whales (3,3%) in the periods 1742–1802 and 1859–1878 no whales were slaughtered there

- Trongisvágur (Suðuroy) with 54 grinds (3,0%) and 6,511 whales (2,6%) in the periods 1733–1803 and 1875–1898 no whales were slaughtered there

- Funningsfjørður (Eysturoy) with 48 grinds (2,7%) and 4,883 whales (1,9%) in the periods 1735–1802 and 1899–1925 no whales were slaughtered there[24]

Districts

Since 1832, the Faroe Islands have been divided into several whaling districts, although there is reason to believe that these districts already existed in some form prior to this date. These whaling districts are the basis for the distribution of the meat and blubber of the pilot whales caught. The catch is distributed in such a way that all the residents of the whaling district are given the same amount of the catch, regardless of whether they took part in the hunt or not. It is important to say that coastal spaces have always been a huge place of socialisation for faroese people,and beaches were a space of hunt, and distribution.

Regulations

At the beginning of the 20th century, proposals to start regulations of the whale hunt began to reach the Faroese legislature. On 4 June 1907, the Danish Governor (in Faroese: amtmaður), as well as the Sysselmann (sheriff), sent the first draft for whaling regulations to the Office of the Exchequer in Copenhagen. In the following years, a number of drafts were debated, and finally in 1932 the first Faroese whaling regulations were introduced. As a part of the Home Rule act of 1948, fishing and hunting (such as whaling) laws and regulations are now governed by the Faroese Parliament.[25][26] Since then, every detail of the pilot whale hunt has been carefully defined in the regulations.[27] This means that the institution of the pilot whale hunt, which had previously largely been based on tradition, became an integrated part of society's legal structure. In the regulations, one has institutionalized old customs and added new ordinances when old customs have proved insufficient or inappropriate.[28] Bureaucratization of such ancient traditions, is making the grind official, and legal, surrounded by rights and duty for the ones who practice it. It only became a marine issue in the late 1980s after the first activists protests. This regulation stated the grind as a political matter, and a governmental responsibility.

Before the enactment of Home-Rule in 1948, the Danish governor had the highest responsibility of supervising a pilot whale hunt. Today, supervision is the responsibility of the Faroese government, Home Rule Government.[25][26] The government is charged with ensuring that the pilot whaling regulations are respected and otherwise answer for preparations. In practice, this means that it is the local legislative representative who holds the highest command in a pilot whale hunt. It is his responsibility to both supervise the hunt and to distribute the catch. Since the grind is a local tradition, the Danish Government considered it was not his duty to deal with the grind.

The hunt

Whale hunting equipment is legally restricted to hooks (blásturkrókur), ropes, mønustingari (a specially-designed Faroese knife to cut the whale's spine, so it dies within seconds) and assessing-poles for measurement. When the men hear the news about the grindaboð (that a whale pod has been discovered near land), fishermen already at sea in their boats sail towards the whales and wait for other boats to arrive. In older times the boats which were used to the whale hunt were the traditional wooden rowing boats. In modern times they use boats with engines; these boats can be wooden boats or other types of boats like fibreglass boats. In the village of Vágur however they have preserved ten old whaling boats, which are wooden rowing boats, the oldest one dates back to 1873.[29] These boats are still in use but mostly for pleasure trips.[30][31] Most of the boats used in whale hunts are small modern fishing boats. In Vágur equipment like ropes and hooks (for the whale's blowhole) are kept in boat houses and only taken out from their place when there is grindaboð in the island of Suðuroy.

Whale drives take place only when a school of whales is sighted close to land, and when sea and weather conditions make this possible. The whaling regulations specify how the school of whales is to be driven ashore. The drive itself works by surrounding the pilot whales with a wide semicircle of boats. On the whaling-foreman's signal, stones attached to lines are thrown into the water behind the pilot whales, thus the boats drive the whales towards an authorised beach or fjord, where the whales that beach themselves. It is not permitted to take whales on the ocean-side of the rope. A pilot whale drive is always under supervision of local authorities: the local grindforeman and/or the sysselman, as stated in the act of 26 January 2017, section 1 and 2.[32][33]

The pilot whales that are not beached were earlier often stabbed in the blubber with a sharp hook, called a sóknarongul, (a kind of gaff) and then pulled ashore. But, after allegations of animal cruelty, the Faroese whalers started using blunt gaffs (in Faroese: blásturongul) in order to hold the beached whale steady and furthermore to pull the whales ashore by their blowholes after being killed. As of 2012, the ordinary gaff is used only to pull killed whales ashore, later it is not used at all. The blunt gaff became generally accepted since its invention in 1993, and it is not only more effective, but it is also thought to be more humane by comparison to the other gaff.[34]

Furthermore, in 1985, the Faroe Islands outlawed the use of spears and harpoons (Faroese: hvalvákn and skutil) in the hunt, as these weapons were considered to be unnecessarily cruel to the whales.[35]

Once ashore, the pilot whale is killed by cutting the dorsal area through to the spinal cord with a special whaling knife, a mønustingari (spinal cord cutter), and after cutting it, the whaler must make sure that the whale is dead, he can do this by touching the whale's eye; before he cuts the neck open, so that as much blood as possible can run from the whale in order to get the best quality of meat. The neck is cut with a grindaknívur, but only after it has been killed.[36] The mønustingari is a new invention which has been legal to use to kill pilot whales with since 2011,[37] and since 1 May 2015 it is the only weapon allowed to slaughter a whale. The length of time it takes for a whale to die varies from a few seconds to a few minutes. Other observers complained that it took up to fifteen minutes for certain whales to die, they noted several cuts were sometimes made before a successful death and that some whales were not even killed properly until a vet finishes the job.[38][39] With the new law which prohibits the whale hunters to stab the whales from the boats, this should not take place any more. According to the new Whaling Law (Grindalógin), it is only allowed to kill the whales from the shore, that means it is not the men who hunt the pilot whales with their boats who are slaughtering the whales, but men who are waiting on the beach with blowhole hooks with rope and spinal cord knives.

These specificities are more than practices, they're rituals, like Margaret Lantis[20] described the Canadian tribes and their whaling traditions. Indeed, she asked herself if the dangerous aspect of the hunt was the reason why it was naturally ritualized. There is an inevitable historical and cultural force of this cult in the tribes, as a community but also an individual relation with this cult and nature. In her research she finds some spatial resemblances between the tribes who comes from approximately the same place. But this text presents a huge lack of information that history cannot fulfill. The documents are not specific enough to establish a truth or a general conclusion. The question she raises in the text can't be fully answered which is a big problem in this article. But in the same way this text reveals more about the way cultural or cultual phenomenon are embedded in the historical context.

Other species of cetacean that may be taken, and their current status

According to Faroese legislation, it is also permitted to hunt certain species of small cetaceans other than pilot whales.[40] These include: bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus), and harbour porpoise (Phocaena phocaena). This section is confronting the Faroese legislation to the IWC International Whaling Commission,[41] a whaling non-governmental Organisation supported by the UN that Faroe Islands did not ratified, and the reality of the field in Faroe. The aim of the IWC is the conservation and management of different species of whales, that control and regulate drives r fisheries like the one in Faroe Islands. This part states what are the IWC recommendations, and the list of other cetaceans than pilot whales.

For example, the bottlenose dolphin,[42] is considered as an endangered species in the Black Sea "Common bottlenose dolphins are considered Least Concern by the IUCN on a global level, but this may be deceiving, as many populations are undergoing serious declines, including: [...] the Black Sea where previous hunting and live captures and ongoing high rates of fisheries bycatch have led to an IUCN Endangered status and a CMS Appendix 1 listing.".

The population figure of 778,000 is accepted by the International Whaling Commission's Scientific Committee. Those in favour of whaling, such as the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission in their 1997 and 1999 reports on the hunt, claim that this is a conservative estimate,[43] whilst others opposed to the hunt, such as the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, cite data that the figure is overestimated. This means that the average kill from 1990–1999 of 956 animals each year represented about 0.1% of the population, which was considered probably sustainable by the IUCN[44] and ACS.[45]

The hunting of these dolphin species, with the exception of harbour porpoises, is carried out in the same way as the pilot whale hunt.

Harbour porpoises are killed with shotguns, and numbers taken must be reported to the relevant district sheriff. According to statistics, the number of harbour porpoises shot is very low — from 0 to 10 animals each year. Harbour Porpoises are present in Belt Sea to the tune of 40 000 according to IWC researches,[46] so the amount of harbour porpoises hunted is not that high compared to the average number of 2012.

Surveys of the size of the Northeast Atlantic pilot whale population have been conducted by the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. These surveys converged on a figure of 778,000 pilot whales.[43] The pilot whale is not registered as an endangered species. The IUCN lists both species of pilot whale as "least concern" in the Red List of Threatened Species.

In its Red List of Threatened Species, the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists both the long-finned and short-finned pilot whales with "least concern" status, according to its 2018 assessment. In a previous assessment in 1996, the organization listed the species in the "lower risk/least concern" category. The IUCN also says that with the 1998 NAMMCO-estimated population size of 778,000 in the eastern North Atlantic, with approximately 100,000 around the Faroes, Faroese catches of 850 per year were "probably sustainable", though the species as a whole was listed as "data deficient" in 2008.[44]

Commercial whaling for larger whale species (fin and minke whales) in the Faroe Islands has not been carried out since 1984. The last whaling station was at Við Áir near Hvalvík, which closed down in 1984. The Faroese government (Mentamálaráðið), Sunda Municipality and Søvn Landsins are restoring it to make it into a maritime museum.[47]

Other species are also killed on rare occasion such as the northern bottlenose whale and Atlantic white-sided dolphin. The northern bottlenose whale is mainly killed when it accidentally swims too close to the beach and cannot return to the water. When the locals find them stranded or nearly stranded on the beach, they kill them and share the meat to all the villagers.[48]

The stranding of the northern bottlenose whale mainly happens in two villages in the northern part of Suðuroy: Hvalba and Sandvík. It is believed that it happens because of a navigation problem of the whale, because there are isthmuses on these places, where the distance between the east and west coasts are short, around one kilometer or so. And for some reason it seems like the bottlenose whale want to take a shortcut through what it thinks is a sound, and too late it discovers, that is on shallow ground and is unable to turn around again. It happened on 30 August 2012, when two northern bottlenose whales swam ashore to the gorge Sigmundsgjógv in Sandvík. Two men who were working on the harbour noticed these whales, and some time later they had either died by themselves or were killed by the locals and then cut up for food for the people of Sandvík and Hvalba (Hvalba municipality).[48]

Impression

During the cut of a pilot whale's spine, its main arteries also get cut. Because of this, the surrounding sea tends to turn a bloody red. This vivid imagery is often used by anti-whaling groups in their campaigns against the hunt. These images of a blood-red sea can have a shocking effect on bystanders. In this regard, the Grind is not a very touristic practice, compared to thuna fishery called "The Mattanza" in Egadi Islands[49]

Since harpoons, spears, and firearms are prohibited, the whalers must be on the shoreline of the water and kill each individual whale. This is notably linked to the fact that since 1986, every torture practiced on a cetacean is punished by the Home Rule Government of Faroe Islands,so the rituals were modified in order to fit the current maritime security imperatives.

Ólavur Sjúrðaberg, the chairman of the Faroese Pilot Whalers’ Association, describes the pilot whale hunt in such a way: "I'm sure that no one who kills his own animals for food is unmoved by what he does. You want it done as quickly and with as little suffering as possible for the animal."[50]

Cultural importance

Pilot whale hunt is an integral part of Faroese social culture. As the attendees of a grindadráp usually are men, women do usually not actively take part in it, but are bystanders or onlookers. This is part of the traditional division of labor concerning pilot whaling which is centuries old,[51] and has only changed little over time, though the method has changed quite a lot, considering that the boats nowadays have engines and most of the original weapons used to slaughter the whales are now forbidden. It is not allowed to hurt the whales in any way, and the killing must be done as fast as possible and can according to the new grind law only be done by using a new kind of weapon which in Faroese is called mønustingari. Another tool which is allowed and must be used is a round hook, which is put into the blowhole of the whale in order to drag the whale ashore. The whale must be ashore or at least be stuck on the seabed before it can be put down.[52] A Russell Fielding research in 2013,[53] on young well-educated faroese citizens and their attachment to the grind tradition, shows that they're widely attached to this tradition as a ritual, but do not consume as much meat as their elders. Men more than women consume blubber and pilot meat, and the less educated people seem to be more attached to this tradition than well-educated people. Also, the possession of a green passport (national symbol in Faroe Islands, opposed to the red Danish passport, more internationalized) is correlated to the participation to the grind. You're more likely to have a green passport if you're participating to the grind in Faroe. Thus we can see here how important must be the grind for the locals, and how the tradition tends to lose its importance in older well educated faroese. Even if whale meat and blubber are very popular in Faroe Islands, the author explains that the opinion grows in disfavor of whaling, as environmental concerns gets crucial aspect in political speeches (this was demonstrated by Charlotte Epstein, who pointed the growing concern of environmental issues and the few states that kept some opposite practices due to subsistences matters).

In Faroese literature and art, grindadráp is an important motif. The grindadráp paintings by Sámal Joensen-Mikines rank internationally as some of his most important. They are part of a permanent exhibition in the Faroese art museum in the capital Tórshavn. The Danish governor (amtmand) of the Faroe Islands, Christian Pløyen (1803–1867), wrote the pilot whaling ballad, a Faroese ballad written in Danish entitled "Grindavísan". It was written during his term of office (1830–1847) and was printed in Copenhagen in 1835.[54]

The Danish chorus line is Raske drenge, grind at dræbe det er vor lyst. In English: Tough boys, to slay the grind that's our desire. or Healthy lads grind to kill - That's what we like.[55]

These old verses are still sung by the Faroese today along with the traditional Faroese chain dance.[56] In recent years the grindavísan has been sung in a more modern way by the Faroese Viking Metal band Týr, the melody is the same and the verses are the same, only much shorter version of the ballad and with instruments.[57]

A survey made by Russell Fielding[58] in 2012 reported an average number of 800 pilot whales killed and 75 dolphins in 2012. This author is studying the grind as a unique historical and traditional practice since 2005. According to him, the grind is practiced and regulated by faroese since approximately 1709, based on Icelanders detailed records. The cultural importance of the Grind in Faroe Islands is social, since people are gathering around a commune history, and ancient shared tradition, which is creating a kind of symbol concerning the grind. The cultural importance of the grind makes it a cultural heritage which is threatened by globalisation and new international challenges. Highly linked to social,economical and political issues in Faroe Islands, we can say that the grind is also a political matter, where institutions, locals, activists and organisation are in debate to know whether or not this cultural tradition must be kept or not. Towards marine biodiversity, especially, this practice raised marine issues, that the IWC and Sea Shepherd want to condemn. The debates and protestations are more detailed in the part "Controversies: is the grind a barbaric ritual, or a traditional heritage ? Maritime security concerns".

Fatal accident in Sandvík in 1915

On Saturday 13 February 1915 there was a whale hunt in Sandvík, which is the northernmost village of Suðuroy. During the drive into the bay of Sandvík an accident occurred, two boats capsized because of rough sea with 15 men on board. 14 of these young men lost their lives in the accident, only one was rescued. The men came from the villages Sandvík and Hvalba. The accident was one of the worst in the maritime history of the Faroe Islands; it has been referred to a Skaðagrindin í Sandvík in Faroese (The Fatal Grind of Sandvík). The only man who survived the accident, Petur í Køkini, wrote a letter on the following day in which he described the accident and his loss of his son and his brother. The letter was written in Danish because the Faroese people were not allowed to be educated in their mother tongue, Faroese, at that time. The letter starts with these sentences:

"It is with great sorrow, that I must write you these lines. Yesterday we have lost our beloved son (Niels Peter Joensen) during a whaling in Sandvík. The sea was so rough that two boats capsized, 9 men on board one and 6 in the other. I was myself on board one of these boats and was the only one who got rescued. Several times I got loose of the boat and was deep down in the sea, but I kept grabbing the boat again. After a long time a boat came to rescue me. You must not think, that I was just glad to be rescued. It was just because of Mariane (his wife) and the daughters. My brother Hans also died. All together 14 young men and boys like Peter. It is an unbelievable grief, both out where he used to work, and not at least here at home."[59]

The pilot whale as a source of food, economic perspectives towards a traditional marine hunt

The economical aspect of the grind is not often discussed, but the outcomes of the hunt are providing meat to the locals for the whole year which is a lot of money savings for the country. We talk here about Blue Economy which is "sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem.".[60] In the case of the grind and fisheries, regulations have been implemented in order to respect the current challenges and prevent environmental issues.

The largest part of traditional Faroese food consists of meat. Because of the rugged, rocky Faroese terrain, grain and vegetables do not grow very well, as only about 2% of the 1,393 km2 is arable land and none is set aside for permanent crops.[61] During the winter months, the Faroe Islanders' only option was to eat mostly salted or dried food (this includes sheep meat, pilot whale meat, seabirds, and fish). This means that over the centuries, the pilot whale has been an important source of nutrition for the isolated population on the North Atlantic archipelago.

The pilot whale meat and blubber are stored, prepared, and eaten in Faroese households. This also means that whale meat is not available at supermarkets. Although the Faroe Islands' main export is fish, this does not include pilot whale meat or blubber. An annual catch of 956 pilot whales[62] (1990–1999) is roughly equivalent to 500 tonnes of meat and blubber, some 30% of all meat produced locally in the Faroe Islands.

Considering the hypothetical whale fishery under the jurisdiction of a nation, the study shows that the optimal level of whaling effort is picked to maximise the resource rent. In a second assumption, we can see that the fisheries linkage also depend on efficiency of fishery management. As ecotourism occurs the reaction of ecotourism to one nation's commercial whaling is negatively impacted. Finally the whaling activity can affect the demand through boycotts, by NGO for instance.The boycotts influence the revenue of a nation if the harvest is higher than the threshold level established. Facing the whale industry, a nation must handle a multidimensional decision regarding the policy they're engaging. In the case of Faroe Islands, the whaling industry and coastal fishery are regulated by the Home Rule Government. Every decision regarding the grind is made by the faroese policy, that prefers culture heritage, than environmental and western ethical alternatives.[63]

Even if the grind is not an trade activity, it represents a big part of the meat consumption in Faroe Islands (30% in 2002), so it has both an economic and environmental costs. The country mainly trades with Denmark, there are also Spain, Germany, and Sweden. They import 26% to Denmark and 20% splat in three for the others. If they increase their production by ceasing the grind, the increase of fuel consumption due to many more imports are going to pollute as much as the grind was supposed to. The environmental impact is not an argument when economical adjustments are in stake.[64]

Recently, the publication of the book “Whales and Nations” of Dorsey, makes an history of the international regulation of whaling, with the massive organisation of the hunt for profit maximisation to nowadays moral on restricting commercialisation. According to the author scientists have a lack of knowledge, and policy makers are not doing much restrictions to control make whaling sustainable. This shows that whaling and by extension grind is an integral part of the maritime safety debate on fisheries management.

Whale meat and blubber as source of carnitine, vitamins and minerals

In 1995 the first Faroese patient with systemic primary carnitine deficiency (SPCD) was diagnosed.[65] Later other patients were found, but nothing was done to find out if the illness was common or if something should be done about it. Not until 2008 when a young woman died just a few days after being diagnosed with SPCD (in the Faroes, the illness is named CTD), actions were finally taken by the Faroese health authorities. The young woman had not been treated, and this caused a big discussion about how to prevent this from happening again. Shortly after, all Faroese people in the Faroes were invited to take a blood sample for a small cost and get it screened for SPCD. Several persons with the illness were found and got treatment immediately. It is now known that several Faroese people have died a sudden death at a young age because of this illness. Around one third of the Faroese population has been screened for SPCD (with a blood sample), and scientists think that at least one of every 1000 inhabitants of the Faroes have the illness. There have also been found elderly people who have survived the illness without treatment. The treatment is to give the patients carnitine supplement. The German physician and scientist Ulrike Steuerwald, who has done research in the Faroe Islands for several years, has argued that the Faroese diet of red meat, like sheep meat and whale meat which contain high amounts of carnitine, may have protected many Faroese people from a sudden death at a young age from SPCD.[66][67] The whale meat contains nutritions like carnitine, taurine and selenium. The concentration of selenium in raw fresh cod fillet and raw fresh pilot whale meat is 28 µg/100g and 185 µg/100g.[68] The whale's blubber is rich in vitamin D, which around half of the elderly population and many amongst the younger generations in the Faroe Islands are lacking. Reasons for this can be changes from traditional food to pizza, chicken, etc.[69] The fat of sea mammals provide excellent sources of vitamins A, D and E.[70]

Food preparation

Whale meat and blubber are Faroese delicacies. Well into the 20th century, meat and blubber from the pilot whale was used to feed people for long periods of time. Everybody got a share, as is the custom to this day.[71] The meat and blubber can be stored and prepared in a variety of ways, in Faroese it is called Tvøst og spik. When fresh, the meat is boiled or served as steaks. A pilot whale steak is called in Faroese: grindabúffur. Whale meat with blubber and potatoes in their skins are put into a saucepan with salt and then boiled for an hour or so. Slivers of the blubber are also a popular accompaniment to dried fish.

The traditional preservation is by salting or outdoor wind-drying.[72] The wind-drying takes around eight weeks. The salting is usually done by putting the meat and the blubber in salt, a little bit of water can be added, it should be so salty, that a potato can float in it. The meat and blubber can be eaten when needed, it can last for a very long time when lying in salt. It can not be eaten directly as it would be too salty, it must be "watered out" for one to 1 1⁄2 day, it depends how salty people like it. After that the meat must be boiled, the blubber can be boiled or eaten as it is. Today many people also freeze the meat and the blubber, but the traditional way of storage is still practiced, particularly in the villages, and the food lasts longer that way. The Faroese people are aware of the fact that the pilot whales, just like many other ocean mammals, are contaminated and that they should not eat the meat and blubber so often. In some areas there are no whalings for years, and then the people there do not have any whale food unless they get some from relatives or friends from other areas who have enough and wish to share.

Sometimes the pilot whale meat and other Faroese food specialties are offered at different public cultural events,[73] but it is also popular at private parties, the Faroese people like to have "kalt borð" (it means "cold table") at family parties and other events,[74] and this table with a variety of cold dishes and cakes often include dried pilot whale meat and salted blubber.

Pollution of the oceans, as a political and health matter

Study in the Faroes of mercury pollution

In 1986-87 more than 1000 Faroese children were enrolled in a long-term study of fish consumption and children's development in the Faroe Islands. The study was led by Philippe Grandjean from the University of Southern Denmark. The researchers took hair samples from the mothers of unborn children and a sample of umbilical cord blood in order to measure prenatal exposure to mercury. At the age of seven, the children participated in some tests which showed that the higher the level of mercury was, the worse the performance. The mercury found in the tested Faroese women and children comes mainly from the consumption of pilot whale.[75] The Health question that concerned the consumption of pilot whales and blubber in Faroe Islands caught meny searchers attention in 1980s like P. Weihe and H. Debes Joensen.[76]

Contaminants found in marine mammals and birds

Regular studies are being made of contaminants of the marine mammals and birds who live in and around the Arctic sea around Greenland and the Faroe Islands as a part of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). The scientist have found high amounts of a variety of contaminants. DEHP (Phthalate) was found in high concentration between 75-161 ng/g wet-weight in all samples.[77]

A June 2003 study of pilot whale tissues conducted in the Faroe Islands had found a rate of 1 to 1.9 ppm in muscle tissue, 5.0 to 8.4 ppm in kidney tissue and 8.4 to 11.8 ppm of mercury in liver tissue.[78] The researches about health risks, because of the staple diet confronts the culture to science, since informations carried out by scientists puts into perspective the potential obsolescence of Feroian rituals.

Both P. Weihe and H. Debes Joensen[76] conducted a review on the bad effects of long-term consumption of pilot whales by R.Weihe. He pointed out a 1977 study and most recent ones, that shows the impact that could have the consumption of pilot whales on nervous system foetal development. The too high rate of mercury contained in the meat is dangerous for the well development of the baby during the pregnancy. It is explained in this article that risks coming from the pilot whales and blubber have been risen from the government in 1980s, where pregnant women were the main preoccupation of the Medical Officer from the Faroe. In 1989, the discovery of high level of mercury and PCB (polychlorinated biphenyls) in blubber and pilot whale meat forced the health authorities of Faroe to recommend the limitation of whales meat consumption of once per week, and blubber once per month. Liver and kidneys should not be eaten at all. R. Weihe has summarized 5 birth cohorts, where he describes the several scientific discoveries. The last cohort was released between 2007 and 2009. In short, consuming regularly pilot whale meat or blubber has a negative effects on the foetal nervous system, affect the blood pressure of the baby (if the mother consumes the meat/blubber), and increase the likelihood of contracting Parkinson's disease. It can also increase the risks of hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and reproductives functions could be aso touched negatively by the daily consumption of the pilot whale meat and blubber. Weihe and Debes Joensen concludes that the content of mercury and PCB in pilot whales are too high to be consumed in an international and European perspective. This is probably due to the pollution from the outside, according to Weihe and Debes Joensen.

Recommendations

Due to pollution, consumption of the meat and blubber is now considered unhealthy. Children and pregnant women are especially at risk, and prenatal exposure to methylmercury and PCBs primarily from the consumption of pilot whale meat has resulted in neuropsychological deficit in children.[79][80]

In November 2008, New Scientist reported that research in the Faroe Islands led to the recommendation by the Faroese government that the consumption of pilot whale meat in the Faroes should stop as it has proven to be too toxic.[81] However, the Faroese government did not forbid the consumption of pilot whale meat, but the advice from Joensen and Weihe resulted in reduced consumption, according to a senior Faroese health official.[82] The health issue of massive fisheries and their consumption of pilot whales on the Faroese population came into the political agenda. This has led to prevention campaigns on the part of the authorities, with the aim of responding to a national health dilemma. However, banning the eating habits of the community, which have become an ancestral tradition, is not an option for the Feroian government.

In June 2011, although the government did not ban the consumption of whale meat, the Faroese Food and Veterinary Authorities sent out an official recommendation regarding the consumption of meat and blubber from the pilot whale.[83] They recommend that because of the pollution of the whale:

- Adults should only eat one portion of pilot whale meat and blubber per month.

- Special advice for women and girls:

- Girls and women should not eat blubber at all until they have finished giving birth.

- Women who plan to get pregnant within three months, pregnant women and women who breastfeed should probably not eat whale meat at all.

- The kidneys and liver of the pilot whales should never be eaten.[84]

The recommendations have an impact on older faroese population, which we can see in Fielding survey,[53] where results are questioning the impact of a controversial tradition on the youth of a nation. For example, most students tends to consume meat than blubber, men more than women, especially in Faroe Islands (probably due to the 1998 scientific warning paper for pregnant women).

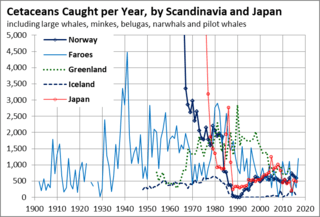

Catches

Records of the drive exist in part since 1584, and continuously from 1709—the longest period of time for statistics existing for any wild animal slaughter in the world.[85]

The catch is divided into shares known in Faroese as a skinn, which is an age-old measurement value that derives from agricultural practices. One skinn equals 38 kg of whale meat plus 34 kg of blubber: in total 72 kg.

| Period | Drives | Whales | Skinn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1709–1950 | 1,195 | 178,259 | 1,360,160 | |

| Period | Drives | Whales | Skinn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951–1960 | 122 | 18,772 | 99,102 |

| 1961–1970 | 130 | 15,784 | 79,588 |

| 1971–1980 | 85 | 11,311 | 69,026 |

| 1981–1990 | 176 | 18,806 | 108,714 |

| 1991–2000 | 101 | 9,212 | 66,284 | |

| Period | Drives | Whales | Skinn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 11 | 918 | 7,447 |

| 2002 | 10 | 626 | 4,263 |

| 2003 | 5 | 503 | 3,968 |

| 2004 | 9 | 1,010 | 8,276 |

| 2005 | 6 | 302 | 2,194 |

| 2006 | 11 | 856 | 6,615 |

| 2007 | 10 | 633 | 5,522 |

| 2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 3 | 310 | 2974 |

| 2010 | 16 | 1107 | 8008 |

| 2011 | 10 | 726 | 4683 |

| 2012 | 12 | 713 | 4962 |

| 2013 | 11 | 1104 | 8302 |

| 2014 | 2 | 48 | 341[86] |

| 2015 | 7 | 508 | 3598 |

| 2016 | 5 | 295 | 2115 |

In 2013, a total of 1524 cetaceans were killed: 1104 pilot whales and 430 white-sided dolphins.[87]

In 2014, at total of 53 cetaceans were killed: 48 pilot whales and 5 northern bottlenose whales which stranded by themselves and after that were butchered for food.[86]

In 2017,[88] 1203 pilot whales were killed, and 488 white sided dolphins.

In 2018,[88] a total of 624 pilot whales, and 256 white-sided dolphins were killed. 5 bottlenose whales have also been caught during the spring and summer drives.

In 2019,[88] 682 pilot whales and 10 white-sided dolphins were killed and also 2 bottlenose whales.

- Long-term annual average catch 1709–1999: 850

- Annual average catch 1900–1999: 1,225

- Annual average catch 1980–1999: 1,511

- Annual average catch 1990–1999: 956

As an interpretation of the figures for whale catches since the 2000s, we can first of all see a certain irregularity. It might be because whale schools are random, and are not a controllable variable. But even if the catches are a bit random, the tendency since the 1950s shows a slowdown in catches (see graphic) in general.

COVID-19 effect

In 2020 the coronavirus pandemic also affected the whale drives in the Faroe Islands. In March 2020 it was forbidden to gather more than 10 persons due to the risk of spreading the virus.[89] In May 2020 there had not been any new case of coronavirus in the Faroe Islands for several weeks and Faroese society opened more up again allowing 100 persons to gather, although with restrictions of personal distancing of one meter.[90] Because of these restrictions and of fear of potential risk of spreading the coronavirus again, the sysselmen of the Faroes decided that as long as these COVID-19 restrictions remain it is forbidden to drive pods of pilotwhales into the bays of the Faroe Islands, as it would be impossible to do so and at the same time keeping one meter distance to each other both in the boats and at the beaches. These new regulations will last at least until 30 June 2020.[91] On 16 June 2020 a pod of 10 pilotwhales were spotted near the coast of Tórshavn/Hoyvík area, it was decided that they should not be killed. In stead som scientists from the National Museum of the Faroe Islands put a transmitter on four of the whales for scientific reasons, so they could follow their journey in the North Atlantic Ocean, to see where and how far they would swim in the ocean.[92][93]

Controversy and interpretations

The controversies about the grind merged in 1980s, with first the health issue, that brought the cultural aspect of the grind itself to the ears of activists. In marine security the threat of a cultural heritage is a global and local challenge. Maintaining marine cultures and structures, are the duty of several actors, like locals, international organisations, governments, or some coastal clusters. The grind is threatened by environmental imperatives, health consequences, and moral revendications. This constructivist vision brings out the concepts of Blue economy, Maritime Domain awareness, and multi-stakeholders perspectives. According to environmental activists, this practice is savage, and violating the Berne Convention, the Bonn Convention and the ASCOBANS (Association on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas signed by the United Nations, and entered in force in 1994) that Faroe Islands ratified. These three conventions are notably stipulating that signatories must protect the cetaceans of their seas, which Denmark is not doing according to activists. Faroese laws and the laws of the international communities allow for the Faroese pilot whale drive,[94] while several international special interest groups object to this practice. The grind is supported by the Faroe government and the Danish government, which was attacked by environmental organisations since 1980s. The most recent attack to the Danish government was launched by Sea Shepherd NGO, in 2017, which referred to the European Commission to force Denmark to pressurize Faroe to stop the grind on the archipelago. It didn't worked out, and the grind is still a legal practice according to the Danish government and the faroe's.

Proponents of Faroese pilot whaling defend it with several arguments. The drive is described as essential to the Faroese culture and provides high quality food to substitute for the islands' inability to sustain land based agriculture and that the number of whales taken are not harmful to the general pilot whale population. The pilot whale slaughter does not exist as a commercial slaughter and is proven as only a communal food distribution among local households. However, whale meat can be sold in restaurants. The slaughter of North Atlantic dolphin populations, at the rate of 0.1% per year, is sustainable for the species.[95] In addition, proponents point to the Faroese law which prohibits causing an animal unnecessary harm, and to the fact that the current method (spinal lance and blunt hook) has been shown to generally cause immediate death in the animal within a second or so. Generally, the locals and the Danish government are the main proponents of pilot whaling practices. They're defending an old tradition, meaningful for this coastal isolated people. Proponents of the whale drive further argue that the pilot whale lives its whole life naturally in its natural environment, the Atlantic Ocean, and then is slaughtered in few minutes, with an average time of death of 30 seconds, in contrast to the fate of conventional livestock. Causing an animal unnecessary or excessive pain and discomfort is also prohibited by the Faroese law. Pointing out cultural rights and the respect of biodiversity and local authorities, the faroese community argues that the grindadràp aims to be a ritual, a social norm that constitute a cultural legacy. Trade and environmental issues are this people's concern, but not in spite of their culture, and especially cultural identity.

Despite the cultural print of the grind, as an ancred tradition, it is considered as atrocious, barbaric, like the faroese anthropologist Joan Pauli Joensen said in 1970s. The distribution of meat is legally regulated by the institution. Since the 1980s, there's an international criticism, from environmentalists mainly. The main argue raised is that they don't need it now to survive, and it is no longer traditional because they don't even use now the traditional boat they used to hunt with. There's just a need to sustain the cultural identity of the island. Since they are embedded in the global economy, the argument of self-sufficiency is no longer valid. The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society was the fiercest detractor of this practice since the 90s. There is a meat waste, which is another argument for the pro banishment of the grind in Faroe Islands. The fact that it is more a festive tradition than an imperative (economical or survival) need for the islanders is considered as a cultural caprice of these people, in order to maintain their standard of living. In an international perspective, we can say that the grind is not well seen, some politicians of Irish and English governments asked their institutions to condemn this practice. The faroese community have been compared to barbaric Vikings, and medieval individuals. Tunas on the other hand, are engaging much less moral, because it is not a symbolic marine specimen in international environmentalist organisations where western ethic prevales. The symbolic dimension is really important as the author says: “The symbolic dimension is obviously important in human classifications of the pecking order of sea creatures As Kate Sanderson argues, ‘[t]he reasons for the persistent and aggressive campaigning to stop Faroese whaling can be found in the nature of grind itself and the ambiguities it presents in relation to predominant cultural perceptions of nature and human society found in the urbanized western world' (1994: 189)." [49] Also the fact that grind is not commercial is adding credits to the protests so it is depicted as a recreation sport.

In 1989, the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society commissioned an animated public information film (narrated by Anthony Hopkins) to raise awareness on the Faroe Islands' whaling of long-finned pilot whales.[96] The film is one minute long and caused controversy when it was released.

For example, G. Herrera, specialized in microeconomics and crossed level environmental studies, and P. Hoagland, oceanographer and searcher at the Marine Policy Center (Delaware), pointed out the importance of marine mammals, notably whales that are valued by human beings, which could explain why whaling is so controversial, and appear to be a big move for nationstates. IWC (International Whales Commission) is the principal commission opposed to whaling industry, and has been funded to manage dwindling whale stocks, and avoid their extinct. Applying the blue economy concept, some countries like Faroe Islands which refused to ratify the moratorium, were in right to do so as they're indigenous people, with subsistence stakes. Whaling industry is much more than whale exploitation, it is also related to ecotourism. There's a conflict between ecotourism and the whaling industry because the nation has to make a choice between this two options, and probably picks what suits it best. For example, whale watching as ecotourism can't occur when there's a whale industry. They have to make a utilitarian choice, which means the most profitable option. As far as consumer boycotts and trade sanction are concerned, the whaling industry is imposing some external costs on nation's economy. The reduction of the tourist activity due to a political or economic decision in a country, is a type of consumer boycott.

Activists like Greenpeace or Sea Shepherd, argue that the whale drive is cruel and unnecessary. During the recent history of the grindadráp, the tools of the catch have modernized. Cellular telephones and radio allow the islands to be alerted to a sighting within the course of minutes. The use of private motorboats gives the whalers more speed and maneuverability on the water. The dull blowhole hook, adopted in response to concerns over cruelty, had the additional effect of further increasing the effectiveness of Faroese attempting to beach the whales. In spite of how such improvements to the tools could make the grindadráp more effective, the number of pilot whales caught, both overall and per whale drive, is less than in preceding centuries.

In the book “The Faroes Grindadráp or Pilot Whale Hunt: The Importance of Its 'Traditional' Status in Debates with Conservationists” [97] of C. Bulbeck and S. Bowlder. This article depicts the grind as “a tradition which conferred strength and substance on the developing Faroese identity and cultural awareness. Pilot whale hunting was rendered in a heroic, nationalistic and masculinist style. ”. Not only does it build an identity, but it reinforced marked social places, and some stereotypes in Feroian society. As a strong identity symbol, the grind is barely questioned by the locals, and yet brings many conceptual debates in maritime security, tradition, and globalisation fields. Conservation organisations and environmentalists like Greenpeace stated that the grind was a sport and not a subsistence activity, which it why it should be banned, regardless of the tradition in stake. If the pro grindadrap accepted some of the conservation organisation compromise in the late 1980s regarding the care of species and the anti-pollution measures( for example, from 1986, every torture of a cetacean is punished by the Home Rule Government), they refused to abandon on such tradition, considering it was a big part of the identity community. Bulbeck and Bowlder points out the western vision of environmentalists, the fact that they produce a certain cultural grip. An interesting point of view has been observed, and I wish to explore it. The authors, through the writings of Sanderson (1991), say that the conservationists (in the way of environmental conservation), are chocked by the grind because it is exercised by white people, where indigenous people are usually black according to western views, which is turning white people as indigenous as “primitive”tribes. This concept could explain why the grind is so controversial, because european white people are still practicing barbaric traditions. The fact that the grind is only a tradition, and is only serving social and symbolic (and a few economical) purposes, is not enough to consider the grind as an essential practice to faroese survival. If western conservationist organisations are not considering the grid utilitarian enough, then, it has to be stopped according to them. The core of this issue is the perception of western thinkers over marine traditions, and what is or should be banned or not on western considerations.

Joining the controversy was a book released in 2011 by the Faroese photographer Regin W. Dalsgaard, titled Two Minutes. The book was a photo-journalistic account of a pilot whale drive in a Faroese bay. The title referred to the time it took a whale to be killed after having been beached.[98]

Nevertheless, as a counter argument the book of Fielding “Environmental Change as a Threat to the Pilot Whale Hunt in the Faroe Islands” [64] is deconstructing the environmentalist view on the grind. Using a specific point of view, by listing some solutions to the grind, and challenges of over-extraction for environmental concerns, are revealing some new perspectives over the grind in Faroe. “Each option carries its own environmental, economic and cultural impact”, as Fielding explains, and the solutions brought by the author have all consequences, that must be taken in account. Faroe Islands, are not likely to stop the grind for environmental issues, because it could be worth for the marine biodiversity, and it could costs them more by increasing the imports. It's the first text of this literature review that shows us that the grind is not not such a bad thing for the environment as it is told by some pro-conservationists.

Faroe Islands, with Greenland and Denmark are part of the Nordic Council of Minister in 2020, which implemented a mission called Vision 2030, which aim is more sustainable lands, and practices.[99] We can read on the website ““The Faroe Islands shared the Danish presidency in both 2005 and 2010. It went well and this is a natural continuation of our work. This time we’re taking on a greater share and will be at the forefront at a political level in parts of the sectors for fisheries, aquaculture, agriculture, food, and forestry. In this way, we’re showing once more that we’re both able and willing to get involved in Nordic co-operation on an equal footing with our Nordic neighbours,” says Bárður á Steig Nielsen, Faroese Minister for Nordic Co-operation." The next steps Faroe Islands is supposed to take with Denmark and Greenland, with blue economy perspectives might or might not include the grind in the main changements Steig Nielsen is talking about. The grind is not part of the program yet, which says a lot on Danish and Faroese positions to activists accusations.

The protection of the marine biodiversity, and the culture is hard to conceptualise, and complicated to intertwine in the political agenda. Such a shift in a coastal space requires time and adapted solutions, for both perpetuating a culture, and fulfilling environmental imperatives. It is a big challenge, that maritime security field has to analyse, in such international contexts. It is facing what A. Arno [100] is calling a cultural currency, which is how a tradition implements a sentiment (in a cultural system way), in a community life. It is an intellectual property, not material, and cultural currencies create performances like commune identity. Facing international economic policy and growing global trade, these economies of sentiment are threatened cultural legacies that communities are boldly trying to preserve. The term production mode is very present to qualify these cultural practices, which structure the organized community. There is no barbarism, but economic and business models that are far removed from the globalized habits that can be found in international relations.

Anti-whaling campaigns

2015 Sleppið Grindini

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society led an operation called 2015 Sleppið Grindini on the Faroe Islands from 15 June until 1 October 2015. The Sea Shepherds works with direct action and there were several confrontations between them and the Faroese/Danish police, and several activists were arrested for disrupting during pilot whale hunts, both on sea and on land. The organisation succeeded in getting big media coverage from larger media from around the world. They took, according to themselves, lots of photos and many hours of video from the whale hunts, which they will use in order to damage Faroese tourism in order to put pressure on the Faroese authorities to end the pilot whale drive hunts. Through an email campaign there was also an attempt of pressuring the Danish Parliament to stop the hunt,[101] but as part of the home rule act of 1948 all laws and regulations relating to fishing and hunting (such as whaling) in the Islands are governed by the Faroese Parliament.[25][26] Just like the year before their campaign led to much public debate in the Faroe Islands and updating of the Faroese Grind Law. Their actions also seems to have pushed the Faroese politics into further self-governing. The Faroese foreign minister Poul Michelsen and the Danish minister of integration Inger Støjberg made an agreement that the Faroe Islands will take over foreign matters.[102][103] The Faroese government from 2011–2015 asked the Danish government if they could forbid Sea Shepherd to enter the Faroe Islands after the 2014 GrindStop campaign had ended and before the 2015 Sleppið Grindini started, but the Danish government said no.[104] The Faroese authorities will take over the responsibilities for foreign affairs sometime in 2016 according to the plan.[105]

The confrontations led to several trials, both in the Faroese court and in Østre Landsret. On 7 August 2015 the Faroese Court passed sentence upon five activists from Sea Shepherd for disturbing the pilot whale hunt in Bøur and Tórshavn on 23 July 2015. The judge found all five guilty in breaking the Grind law and they were fined 5,000 to 35,000 DKK and the Sea Shepherd Global was fined 75,000 DKK.[106] The five Sea Shepherd activists appealed to the higher court, Østre Landsret, and the Public Prosecutor counter-appealed. The case was treated in Østre Landsret in Tórshavn on 9 and 10 March 2016. One week later, on 17 March 2016 the court changed some of the sentences of the Faroese court, some were lowered and the one of 5,000 DKK was raised to 12,500 DKK.[107] Sea Shepherd refuses to pay the fines. The public prosecutor prepared another case against the Sea Shepherd, where the prosecutor says that people from Sea Shepherd had put several lives at risk, including a 10-year-old boy, two Faroese seamen and two police officers, by sailing recklessly in front of and across of the boats which were driving the pod of whales towards the beach, and colliding with a boat from the fishing inspection authorities.[107]

There is video footage filmed by one of Sea Shepherd UK's covert crew on Operation Bloody Fjords 2018 in the Faroe Islands.[108]

Hunting pictures

Cutting up of pilot whale in Klaksvík.

Cutting up of pilot whale in Klaksvík. Dolphins gathered on a concrete area in Hvalba, August 2006.

Dolphins gathered on a concrete area in Hvalba, August 2006. Sea water colored by the blood of pilot whale in Hvalba.

Sea water colored by the blood of pilot whale in Hvalba.

Photographs in the media of the pilot whale drive display a red sea soaked in blood with the bodies of dead pilot whales. These images cause outrage worldwide. Proponents of the whale drive will defend these images saying that blood is a natural consequence of any animal slaughter and that those who have been outraged have been alienated from the process and basic consequences of animal food production.

See also

Notes and references

- theecologist.org

- Barrat, Harry (3 February 2014). "Whaling in the Faroe Islands: a cruel and unnecessary ritual or sustainable food practice?". The Knowledge. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Duignan, Brian (26 April 2010). "The Faroe Islands Whale Hunt". Encyclopædia Britannica - Advocacy for Animals. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Walker, Harlan (1995). Disappearing Foods: Studies in Foods and Dishes at Risk. ISBN 9780907325628. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- logir.fo

- Grind | Hagstova Føroya

- "Grinds de 2000 à 2013". www.whaling.fo/ Catch figures. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.

- Bertholdsen, Áki (5 March 2015). "Nú eru 1380 føroyingar klárir at fara í grind" (in Faroese). Sosialurin - in.fo. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Løgtingslóg um grind og annan smáhval, sum seinast broytt við løgtingslóg nr. 93 frá 22. juni 2015" (in Faroese). Logir.fo. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- landslaeknin.fo

- MacKenzie, Debora (28 November 2008). "Faroe islanders told to stop eating 'toxic' whales". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- "Kyksilvur í grind". Archived from the original on 6 February 2015.

- Weihe P., Debes Joensen H. “Dietary Recommendations Regarding Pilot Whale Meat and Blubber in the Faroe Islands”, International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71:1, 18594, 2012

- Bueger, Christian (March 2015). "What is maritime security?". Marine Policy. 53: 159–164. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.005.

- Bloch, Dorete (2014). "Um døglingar í Føroyum" (PDF) (in Faroese). Føroya Náttúrugripasavn. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- van Ginkel R. “Killing the giants of the sea: contentious heritage and the politics of culture”. Journal of Mediterranean Studies 15, 71–98, 2005

- Killing Methods and Equipment in the Faroese Pilot Whale Hunt – English translation of a working paper by senior veterinarian, Jústines Olsen, originally presented in Danish at the NAMMCO Workshop on Hunting Methods for marine mammals, held in Nuuk, Greenland, in February 1999.

- Jústines Olsen (1999), Killing methods and equipment in the Faroese pilot whale hunt, article retrieved on 21 June 2008. Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Heimabeiti.fo, Grindayvirlit 1584 – 2010 (Grind statistics from 1584 – 2010), the website is maintained by a former sysselmann in the Faroe Islands.

- Lantis M. The Alaskan whale cult and its affinities. American Anthropologist 40, 438–464, 1938.

- Fielding Russell, “Coastal geomorphology and culture in the spatiality of whaling in the Faroe Islands Area”, Vol. 45, No. 1 (MARCH 2013), pp. 88-97.

- kunngerdarportalur.fo. (Faroese law, which names the authorized locations where whales may be slaughtered for food)

- heimabeiti.fo

- heimabeiti.fo – Ymisk hagtøl um grind (Various statistics about whaling in the Faroes)

- "Home Rule Act of the Faroe Islands". Statsministeriet (State Department of Denmark). Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Special Faeroes Affairs (Appendix)" (PDF). Statsministeriet (State Department of Denmark). Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- The current Grind law of 2013 (Kunngerð um grind) Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Joensen, Jóan Pauli, Pilot Whaling in the Faroe Islands. Ethnologia Scandinavica 1976, Lund

- grindabatar.com

- grindabatar.com, Grindabátarnir og summarið 2014

- Sudurras.fo, Grindabátarnir í Vági summarið 2014 Archived 24 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kunngerð no. 9 frá 26. januar 2017 um grind og annan smáhval". logir.fo. Lógasavnið, the official Faroese law publication. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "Kunngerð um grind". djoralaekni.com. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "Grindareglugerðin verður endurskoðað" (in Faroese). Heimabeiti.fo. 16 October 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Bloch, Dorete (2007). "Grind og grindahvalur" (PDF) (in Faroese). Føroya Náttúrugripasavn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- logir.fo Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- heimabeiti.fo

- Thornton, A. et Gibson J., Pilot Whaling in the Faroe Islands: A Second Report, Londres, Environmental Investigation Agency, 1985

- Bulbeck C. et Bowdler S., « The Faroes grindadràp or pilot whale hunt. », Australian archaeology, 67, décembre 2008

- Olsen, J. (1999) Killing Methods and Equipment in the Faroese Pilot Whale Hunt, NAMMCO/99/WS/2

- https://iwc.int/home

- https://iwc.int/bottlenose-dolphin

- "NAMMCO 1997 and 1999 report on the hunt" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Taylor, B.L.; Baird, R.; Barlow, J.; Dawson, S.M.; Ford, J.; Mead, J.G.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Wade, P.; Pitman (2008). "Globicephala melas". www.iucnredlist.org. IUCN. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Pilot Whale Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 26 July 2015

- https://iwc.int/estimate

- MMR.Sansir.net

- "Tíðindi - Føroyski portalurin - portal.fo". portal.fo. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- van Ginkel R. “Killing the giants of the sea: contentious heritage and the politics of culture”. Journal of Mediterranean Studies 15, 71–98, 2005.

- "Marine Hunters: Modern and Traditional". High North Alliance. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- "Grindaveiða" (in Faroese). Føringatíðindi. 16 March 1899. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Vestergaard, Jacob (5 July 2013). "Kunngerð um grind" (in Faroese). The Faroese Government. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Fielding Russell, “Whaling Futures: a Survey of Faroese and Vincentian Youth on the Topic of Artisanal Whaling”, Society & Natural Resources, 26:7, 810-826, 2013

- "Grindavísan" (PDF) (in Danish). Eysturoyar Dansifelag. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- "Tyr - Grindavisan" (in Danish and English). YouTube. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Grindavísan on YouTube

- Týr's version of Grindavísan

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/9/140911-faroe-island-pilot-whale-hunt-animals-ocean-science/

- Fiskimannafelag.fo – FF-Blaðið, 3. februar 2005, Skaðagrindin í Sandvík í 1915, page 9 Archived 9 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine (the article is in Faroese, the letter in Danish)

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2017/06/06/blue-economy

- "The World Factbook – Faroe Islands". Central Intelligence Agency. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- "Pilot Whale catches in the Faroe Islands 1900–2000". Whaling.fo. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- Hoagland Porter, Herrera Guillermo E. , “Commercial whaling, tourism and boycotts: an economic perspective”, Marine Policy n°30, 2006, p.261-269.

- Fielding Russell “Environmental Change as a Threat to the Pilot Whale Hunt in the Faroe Islands”, Department of Geography and Anthropology Louisiana State Museum, Blackwell Publishing, 2010.

- Hmr.fo – The Faroese Ministry of Health Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Issuu.com – Vísindavøkublaðið – Reytt kjøt hevur vart føroyingar móti CTD (Red meat has rescued Faroese people from dying from SPCD)

- Oyggjatidindi.com, Loksins kom svarið: – Carnitin er í tvøsti. Written by John Jensen who has lost a son because of SPCD, published in 2011

- "Setur.fo – The University of the Faroe Islands – Heilsufremjandi selen í tvøsti". Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- in.fo – Hetta skalt tú eta fyri at fáa nokk av D vitaminum (What should you eat in order to get enough vitamin D)

- "Setur.fo – Healthy Compounds in Meat and Blubber of Whales and Seals, 2013, by Hóraldur Joensen" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- "Faroe Islands tourist guide 2007—Food from the clean waters". Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2006.