Voting machine

A voting machine is a machine used to record or tally votes. The first voting machines were mechanical but it is increasingly more common to use electronic voting machines. Traditionally, a voting machine has been defined by its mechanism, and whether the system tallies votes at each voting location, or centrally.

| Election technology |

|---|

| Terminology |

|

| Testing |

|

| Technology |

| Manufacturers |

|

Voting machines differ in usability, security, cost, speed, accuracy, and ability of the public to oversee elections. Machines may be more or less accessible to voters with different disabilities.

Tallies are simplest in parliamentary systems where just one choice is on the ballot, and these are often tallied manually. In other political systems where many choices are on the same ballot, tallies are often done by machines to give quick results.

Historical machines

The first use of paper ballots was in Rome in 139 BCE, and their first use in the United States was in 1629 to select a pastor for the Salem Church.[1]

Mechanical voting

Balls. The first major proposal for the use of voting machines came from the Chartists in 1838.[2] Among the radical reforms called for in The People's Charter were universal suffrage and voting by secret ballot. This required major changes in the conduct of elections, and as responsible reformers, the Chartists not only demanded reforms but described how to accomplish them, publishing Schedule A, a description of how to run a polling place, and Schedule B, a description of a voting machine to be used in such a polling place.[3][4]

The Chartist voting machine, attributed to Benjamin Jolly of 19 York Street in Bath, allowed each voter to cast one vote in a single race. This matched the requirements of a British parliamentary election. Each voter was to cast his vote by dropping a brass ball into the appropriate hole in the top of the machine by the candidate's name. Each voter could only vote once because each voter was given just one brass ball. The ball advanced a clockwork counter for the corresponding candidate as it passed through the machine, and then fell out the front where it could be given to the next voter.

Buttons. In 1875, Henry Spratt of Kent received a U.S. patent for a voting machine that presented the ballot as an array of push buttons, one per candidate.[5] Spratt's machine was designed for a typical British election with a single plurality race on the ballot.

In 1881, Anthony Beranek of Chicago patented the first voting machine appropriate for use in a general election in the United States.[6] Beranek's machine presented an array of push buttons to the voter, with one row per office on the ballot, and one column per party. Interlocks behind each row prevented voting for more than one candidate per race, and an interlock with the door of the voting booth reset the machine for the next voter as each voter left the booth.

A Psephograph was patented by Italian inventor Boggiano in 1907.[7]

Lenna Winslow's 1910 voting machine was designed to offer all the questions on the ballot to men and only some to women because women often had partial suffrage, e.g. being allowed to vote on issues but not candidates.[8][9]

Dials. By July 1936, IBM had mechanized voting and ballot tabulation for single transferable vote elections. Using a series of dials, the voter could record up to twenty ranked preferences to a punched card, one preference at a time. Write-in votes were permitted. The machine prevented a voter from spoiling their ballot by skipping rankings and by giving the same ranking to more than one candidate. A standard punched-card counting machine would tabulate ballots at a rate of 400 per minute.[10]

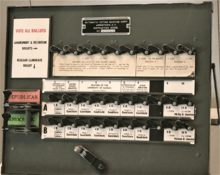

Levers. Lever machines were commonly used in the United States until the 1990s. In 1889, Jacob H. Myers of Rochester, New York, received a patent for a voting machine that was based on Beranek's 1881 push button machine.[11] This machine saw its first use in Lockport, New York, in 1892.[12] In 1894, Sylvanus Davis added a straight-party lever and significantly simplified the interlocking mechanism used to enforce the vote-for-one rule in each race.[13] By 1899, Alfred Gillespie introduced several refinements. It was Gillespie who replaced the heavy metal voting booth with a curtain that was linked to the cast-vote lever, and Gillespie introduced the lever by each candidate name that was turned to point to that name in order to cast a vote for that candidate. Inside the machine, Gillespie worked out how to make the machine programmable so that it could support races in which voters were allowed to vote for, for example, 3 out of 5 candidates.[14]

On December 14, 1900, the U.S. Standard Voting Machine Company was formed, with Alfred Gillespie as one of its directors, to combine the companies that held the Myers, Davis, and Gillespie patents.[15] By the 1920s, this company (under various names) had a monopoly on voting machines, until, in 1936, Samuel and Ransom Shoup obtained a patent for a competing voting machine.[16] By 1934, about a sixth of all presidential ballots were being cast on mechanical voting machines, essentially all made by the same manufacturer.[17]

Commonly, a voter enters the machine and pulls a lever to close the curtain, thus unlocking the voting levers. The voter then makes his or her selection from an array of small voting levers denoting the appropriate candidates or measures. The machine is configured to prevent overvotes by locking out other candidates when one candidate's lever is turned down. When the voter is finished, a lever is pulled which opens the curtain and increments the appropriate counters for each candidate and measure. At the close of the election, the results are hand copied by the precinct officer, although some machines could automatically print the totals. New York was the last state to stop using these machines, under court order, by the fall of 2009.[18][19]

Punched card voting

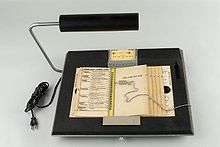

Punched card systems employ a card (or cards) and a small clipboard-sized device for recording votes. Voters punch holes in the cards with a ballot marking device. Typical ballot marking devices carry a ballot label that identifies the candidates or issues associated with each punching position on the card, although in some cases, the names and issues are printed directly on the card. After voting, the voter may place the ballot in a ballot box, or the ballot may be fed into a computer vote tabulating device at the precinct.

The idea of voting by punching holes on paper or cards originated in the 1890s[20] and inventors continued to explore this in the years that followed. By the late 1890s John McTammany's voting machine was used widely in several states. In this machine, votes were recorded by punching holes in a roll of paper comparable to those used in player pianos, and then tabulated after the polls closed using a pneumatic mechanism.

Punched-card voting was proposed occasionally in the mid-20th century,[21] but the first major success for punched-card voting came in 1965, with Joseph P. Harris' development of the Votomatic punched-card system.[22][23][24] This was based on IBM's Port-A-Punch technology. Harris licensed the Votomatic to IBM.[25] William Rouverol built the prototype system.

The Votomatic system[26] was very successful. By the 1996 Presidential election, some variation of the punched card system was used by 37.3% of registered voters in the United States.[27]

Votomatic style systems and punched cards received considerable notoriety in 2000 when their uneven use in Florida was alleged to have affected the outcome of the U.S. presidential election.

Current voting machines

Optical scan (marksense)

In an optical scan voting system, or marksense, each voter's choices are marked on one or more pieces of paper, which then go through a scanner. The scanner creates an electronic image of each ballot, interprets it, creates a tally for each candidate, and usually stores the image for later review.

The voter may mark the paper directly, usually in a specific location for each candidate.

Or the voter may select choices on an electronic screen, which then prints the chosen names, and a bar code or QR code summarizing all choices, on a sheet of paper to put in the scanner.[28] This screen and printer is called an electronic ballot marker (EBM) or ballot marking device (BMD), and voters with disabilities can communicate with it by headphones, large buttons, sip and puff, or paddles, if they cannot interact with the screen or paper directly. Typically the ballot marking device does not store or tally votes. The paper it prints is the official ballot, put into a scanning system which counts the barcodes, or the printed names can be hand-counted, as a check on the machines.[29] Most voters do not look at the paper to ensure it reflects their choices, and when there is a mistake, 93% of voters do not report it to poll workers.[30] Candidates are represented in the bar code or QR code as numbers, so if the numbering system is not aligned in the ballot marking device and the scanner, votes will be tallied for the wrong candidates.

Errors in optical scans

If a bug or hack makes the bar code identify different candidates from the names chosen and printed by the voter, the discrepancy may not be noticed, and the wrong winner will be declared.

Scanners have a row of photo-sensors which the paper passes by, and they record light and dark pixels from the ballot. A black streak results when a scratch or paper dust causes a sensor to record black continuously.[31][32] A white streak can result when a sensor fails.[33] In the right place, such lines can indicate a vote for every candidate or no votes for anyone.

Software can miscount; if it miscounts drastically enough, people notice and check.

- In a Pennsylvania election the software under-counted one candidate by 99%, reporting 164 votes, compared to 26,142 found in a subsequent hand-count, which changed the candidate's loss to a win.[34]

- In a Yakima WA election 24 voters' choices on 4 races were ignored by a faulty scanner which created a white streak down the ballot.[33]

- In a Maryland election, a comparison of two scanning systems on the same ballots revealed that (a) 1,972 ballot images were incorrectly left out of one system, (b) one system incorrectly ignored many votes for write-in candidates,[35] (c) shadows from paper folds were sometimes interpreted as names written in on the ballot, (d) the scanner sometimes pulled two ballots at once, scanning only the top one, (e) the ballot printers sometimes left off certain candidates, (f) voters often put a check or X instead of filling in an oval, which software has to adapt to, and (g) a scratch or dirt on a scanner sensor put a black line on many ballot images, causing the appearance of voting for more than the allowed number of candidates, so those votes were incorrectly ignored.[31][32]

- In a New York City election when the air was humid, ballots jammed in the scanner, or multiple ballots went through a scanner at once, hiding all but one.[36]

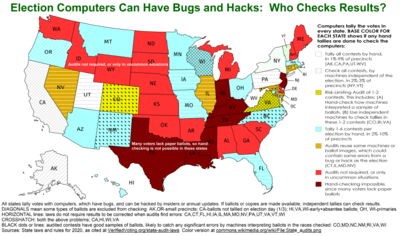

Some US states check a small number of places by hand-counting or use of machines independent of the original election machines.[37]

Cost of scanning systems

Total cost of machines, maintenance and printing for 10 years in Georgia, starting 2020 cost has been estimated at $113 million to 224 million if most voters mark their own paper ballots and a marking device is available at each polling place for voters with disabilities. The range depends on printing cost per ballot and number of extra ballots printed to avoid running out. The estimate is $203 million if all voters use ballot marking devices.[38]

The capital cost of machines in 2019 in Pennsylvania is $11 per voter if most voters mark their own paper ballots and a marking device is available at each polling place for voters with disabilities, compared to $23 per voter if all voters use ballot marking devices.[39]

New York has an undated comparison of capital costs and a system where all voters use ballot marking devices costing over twice as much as a system where most do not. The authors say extra machine maintenance would exacerbate that difference, and printing cost would be comparable in both approaches.[40]

Direct-recording electronic (DRE)

In a DRE voting machine system, a touch screen displays choices to the voter, who selects choices, and can change her mind as often as needed, before casting the vote. Staff initialize each voter once on the machine, to avoid repeat voting. Voting data are recorded in memory components, and can be copied out at the end of the election.

The system may also provide a means for communicating with a central location for reporting results and receiving updates,[41] which is an access point for hacks and bugs to arrive.

Some of these machines also print names of chosen candidates on paper for the voter to verify, though less than 40% verify.[29] These names on paper are kept behind glass in the machine, and can be used for election audits and recounts if needed. The tally of the voting data is stored in a removable memory component and in bar codes on the paper tape. The paper tape is called a Voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT). The VVPATs can be tallied at 20-43 seconds of staff time per vote (not per ballot).[42][43]

For machines without VVPAT, there is no record of individual votes to check.

Errors in DRE

This approach can have software errors. It does not include scanners, so there are no scanner errors. When there is no paper record, it is hard to notice or research most errors.

- A 2018 study of direct-recording voting machines (iVotronic) without VVPAT in South Carolina found that every election from 2010-2018 had some memory cards fail. The investigator also found that lists of candidates were different in the central and precinct machines, so 420 votes which were properly cast in the precinct were erroneously added to a different contest in the central official tally, and unknown numbers were added to other contests in the central official tallies. The investigator found the same had happened in 2010. There were also votes lost by garbled transmissions, which the state election commission saw but did not report as an issue. 49 machines reported that their three internal memory counts disagreed, an average of 240 errors per machine, but the machines stayed in use, and the state evaluation did not report the issue, and there were other error codes and time stamp errors.[44][45]

- The only forensic examination which has been done of direct-recording software files was in Georgia in 2020, and found that one or more unauthorized intruders had entered the files and erased records of what it did to them. In 2014-2017 an intruder had control of the state computer in Georgia which programmed vote-counting machines for all counties. The same computer also held voter registration records. The intrusion exposed all election files in Georgia since then to compromise and malware. Public disclosure came in 2020 from a court case.[46][47][48] Georgia did not have paper ballots to measure the amount of error in electronic tallies. The FBI studied that computer in 2017, and did not report the intrusion.[49][46]

- In a 2011 NJ election a programming error in a machine without a VVPAT gave two candidates low counts. They collected more affidavits by voters who voted for them than the computer tally gave them, so a judge ordered a new election which they won.[50]

- A 2007 study for the Ohio Secretary of State reported on election software from ES&S, Premier and Hart. Besides the problems it found, it noted that all "election systems rely heavily on third party software that implement interfaces to the operating systems, local databases, and devices such as optical scanners... the construction and features of this software is unknown, and may contain undisclosed vulnerabilities such trojan horses or other malware."[51]

Location of tallying

Optical scans can be done either at the place of voting,"precinct", or in another location. DRE machines always tally at the precinct.

Precinct-count voting system

A precinct-count voting system is a voting system that tallies ballots at the polling place. Precinct-count machines typically analyze ballots as they are cast. This approach allows for voters to be notified of voting errors such as overvotes and can prevent spoilt votes. After the voter has a chance to correct any errors, the precinct-count machine tallies that ballot. Vote totals are made public only after the close of polling. DREs and precinct scanners have electronic storage of the vote tallies and may transmit results to a central location over public telecommunication networks.

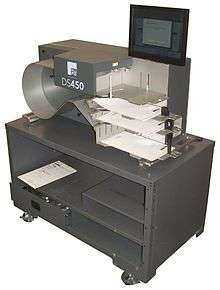

Central-count voting system

A central count voting system is a voting system that tallies ballots from multiple precincts at a central location. Central count systems are also commonly used to process absentee ballots.

Central counting can be done by hand, and in some jurisdictions, central counting is done using the same type of voting machine deployed at polling places, but since the introduction of the Votomatic punched-card voting system and the Norden Electronic Vote Tallying System in the 1960s, high speed ballot tabulators have been in widespread use, particularly in large metropolitan jurisdictions. Today, commodity high-speed scanners sometimes serve this purpose, but special-purpose ballot scanners are also available that incorporate sorting mechanisms to separate tallied ballots from those requiring human interpretation.[52]

Voted ballots are typically placed into secure ballot boxes at the polling place. Stored ballots and/or Precinct Counts are transported or transmitted to a central counting location. The system produces a printed report of the vote count, and may produce a report stored on electronic media suitable for broadcasting, or release on the Internet.

The Advanced Voting Solutions WINvote voting machine in Arlington County, Virginia.

The Advanced Voting Solutions WINvote voting machine in Arlington County, Virginia. A Diebold DRE voting machine used in Maryland 2004.

A Diebold DRE voting machine used in Maryland 2004. The TallyVoting Tally1 DRE in testing in Washington, DC.

The TallyVoting Tally1 DRE in testing in Washington, DC. A Brazilian DRE voting machine

A Brazilian DRE voting machine ES&S iVotronic DRE Voting machine used in Issy-les-Moulineaux in 2007 French presidential election in 2007.

ES&S iVotronic DRE Voting machine used in Issy-les-Moulineaux in 2007 French presidential election in 2007. ISG TopVoter, a voting machine specifically designed for disabled voters.

ISG TopVoter, a voting machine specifically designed for disabled voters. The Shouptronic 1242 DRE voting machine, later sold as the Danaher ElecTronic 1242.

The Shouptronic 1242 DRE voting machine, later sold as the Danaher ElecTronic 1242. A voting machine designed by Alfred J. Gillespie and marketed by the Standard Voting Machine Company of Rochester, New York from the late 1890s.

A voting machine designed by Alfred J. Gillespie and marketed by the Standard Voting Machine Company of Rochester, New York from the late 1890s. A mechanical lever voting machine still being used in 2008 in Kingston, New York.

A mechanical lever voting machine still being used in 2008 in Kingston, New York. DRE voting machine used for Indian general elections

DRE voting machine used for Indian general elections- McTammany player-piano roll voting machine, 1912.

Voting Machine in India

Voting Machine in India

See also

- ACCURATE

- Ballot

- Election ink

- Brazilian voting machine

- Electoral system

- Electronic voting

- Indian voting machines

- Open Voting Consortium

- Postal voting

- Safevote

- Security seal

- Vote counting system

- Voting system

References

- Jones, Douglas W.. A Brief Illustrated History of Voting. THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA Department of Computer Science.

- Douglas W. Jones, Early Requirements for Mechanical Voting Systems, First International Workshop on Requirements Engineering for E-voting Systems, Aug. 31, 2009, Atlanta. (author's copy).

- The People's Charter with the Address to the Radical Reformers of Great Britain and Ireland and a Brief Sketch of its Origin Elt and Fox, London, 1848; obverse of title page.

- The People's Charter 1839 Edition, in the radicalism collection of the University of Aberdeen.

- H. W. Spratt, Improvement in Voting Apparatus, U.S. Patent 158,652, Jan 12. 1875.

- A. C. Beranek, Voting Apparatus, U.S. Patent 248,130g, Oct. 11, 1881.

- The Graphic : an illustrated weekly newspaper. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. London : Graphic. 1869.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kindy, David (June 26, 2019). "The Voting Machine That Displayed Different Ballots Based on Your Sex". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Lenna Winslow, U.S. patent 963,105, which drew from her earlier voting machine designs.

- Hallett, George H. (July 1936). "Proportional representation". National Municipal Review. 25 (7): 432–434. doi:10.1002/ncr.4110250711. ISSN 0190-3799.

- Jacob H. Myers, Voting Machine, U.S. Patent 415,549, Nov. 19, 1889.

- Republicans Carry Lockport; The New Voting Machine Submitted to a Practical Test, in the New York Times, Wed. Apr. 13, 1892; page 1.

- S. E. Davis, Voting Machine, U.S. Patent 526,668, Sept. 25, 1894.

- A. J. Gillespie, Voting-Machine, U.S. Patent 628,905, July 11, 1899.

- The Manual of Statistics: Stock Exchange Hand-book, 1903, The Manual of Statistics Company, New York, 1903; page 773.

- Samuel R. Shoup and Ransom F. Shoup, Voting Machine, U.S. Patent 2,054,102, Sept. 15, 1936.

- Joseph Harris, Voting Machines, Chapter VII of Election Administration in the United States, Brookings, 1934; pages 249 and 279–280.

- "Lever voting machines get a reprieve in NY", Press & Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), August 10, 2007

- Ian Urbina. States Prepare for Tests of Changes to Voting System, New York Times, 5 Feb 2008

- Kennedy Dougan, Ballot-Holder, U.S. Patent 440,545, Nov. 11, 1890.

- Fred M. Carroll (IBM), Voting Machine, U.S. Patent 2,195,848, Apr. 2, 1940.

- Joseph P. Harris, Data Registering Device, U.S. Patent 3,201,038, Aug. 17, 1965.

- Joseph P. Harris, Data Registering Device, U.S. Patent 3,240,409, Mar. 15, 1966.

- Harris, Joseph P. (1980) Professor and Practitioner: Government, Election Reform, and the Votomatic, Bancroft Library

- IBM Archive: Votomatic

- "Votamatic". Verified Voting Foundation. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Punchcards, a definition Archived 2006-09-27 at the Wayback Machine". Federal Election Commission

- "Ballot Marking Devices". Verified Voting. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Cohn, Jennifer (2018-05-05). "What is the latest threat to democracy?". Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Bernhard, Matthew, Allison McDonald, Henry Meng, Jensen Hwa, Nakul Bajaj, Kevin Chang, J. Alex Halderman (2019-12-28). "Can Voters Detect Malicious Manipulation of Ballot Marking Devices?" (PDF). Halderman. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Walker, Natasha (2017-02-13). "2016 Post-Election Audits in Maryland" (PDF). Elections Advisory Commission. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- Ryan, Tom and Benny White (2016-11-30). "Transcript of Email on Ballot Images" (PDF). Pima County, AZ. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Gideon, John (2005-07-05). "Hart InterCivic Optical-Scan Has A Weak Spot". www.votersunite.org. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Corasaniti, Nick (2019-11-30). "A Pennsylvania County's Election Day Nightmare Underscores Voting Machine Concerns". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Lamone, Linda (2016-12-22). "Joint Chairman's Report on the 2016 Post-Election Tabulation Audit" (PDF). Maryland State Board of Elections. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- MacDougall, Ian (2018-11-07). "What Went Wrong at New York City Polling Places? It Was Something in the Air. Literally". Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "State Audit Laws". Verified Voting. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- Fowler, Stephen. "Here's What Vendors Say It Would Cost To Replace Georgia's Voting System". Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Deluzio, Christopher, Kevin Skoglund (2020-02-28). "Pennsylvania Counties' New Voting Systems Selections: An Analysis" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- "NYVV - Paper Ballots Costs". www.nyvv.org. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- 2005 Voluntary Voting System Guidelines Archived 2006-02-08 at the Wayback Machine from the US Election Assistance Commission

- Theisen, Ellen (2005-06-14). "Cost Estimate for Hand Counting 2% of the Precincts in the U.S." (PDF). VotersUnite.org. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "VOTER VERIFIED PAPER AUDIT TRAIL Pilot Project Report" (PDF). Georgia Secretary of State. 2007-04-10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-26. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Buell, Duncan (2018-12-23). Analysis of the Election Data from the 6 November 2018 General Election in South Carolina (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Freed, Benjamin (2019-01-07). "South Carolina voting machines miscounted hundreds of ballots, report finds". Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Lamb, Logan (2020-01-14). "SUPPLEMENTAL DECLARATION OF LOGAN LAMB" (PDF). CourtListener. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- "Coalition Plaintiffs' Status Report, pages 237-244". Coalition for Good Governance. 2020-01-16. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- Bajak, Frank (2020-01-16). "Expert: Georgia election server showed signs of tampering". Associated Press. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- Zetter, Kim. "Will the Georgia Special Election Get Hacked?". Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Thibodeau, Patrick (2016-10-05). "If the election is hacked, we may never know". Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- McDaniel; et al. (2007-12-07). EVEREST: Evaluation and Validation of Election-Related Equipment, Standards and Testing (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simons, Broken Ballots, CSLI Publications, 2012; see Section 4.1 Central-Count Machines, pages 64-65, and Figure 21, page 73.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Voting machines. |

Election administration

Informational

- The Election Technology Library research list – A comprehensive list of research relating to technology use in elections.

- E-Voting information from ACE Project

- AEI-Brookings Election Reform Project

- Electronic Voting Systems at Curlie

- Selker, Ted Scientific American Magazine Fixing the Vote October 2004

- The Machinery of Democracy: Voting System Security, Accessibility, Usability, and Cost from Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law

- Who's who in election technology

- Caltech/ MIT Voting Technology Project

- Black Box Voting book

- Keiper, Frank (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–218.