Voice of God

In Judaism bat kol or bat ḳōl (Hebrew: בּת קול, literally "daughter of voice", voice of God) is a "heavenly or divine voice which proclaims God's will or judgment."[1] It signifies the ruach ha-kodesh (רוח הקודש, "the spirit of holiness") or serves as a metonym for God; "but it differed essentially from the Prophets", though these were delegates or mouthpieces of ruaḥ ha-kodesh.[1]

In Christianity and Islam, the voice of God (Latin: vox dei; Arabic: صوت الله) is a "heavenly or divine voice proclaims God's will or judgment."[1] It is "identified with the Holy Spirit, even with God; but it differed essentially from the Prophets, though these spoke as the medium of the Holy Spirit."[1]

In art it is represented by the Hand of God.

Hebrew Bible

In the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament the characteristic attributes of the voice of God are the invisibility of the speaker and a certain remarkable quality in the sound, regardless of its strength or weakness. A sound proceeding from some invisible source was considered a heavenly voice, since the mass revelation on Sinai was given in that way in Deuteronomy 4:12: "Ye heard the voice of the words, but saw no similitude; only ye heard a voice". In this account, God reveals himself to man through his organs of hearing, not through those of sight. Even the prophet Ezekiel, who sees many visions, "heard a voice of one that spoke" (Ezek 1:28); similarly, Elijah recognized God by a "still, small voice," and a voice addressed him (I Kings 19:12–13; compare Job 4:16); sometimes God's voice rang from the heights, from Jerusalem, from Zion (Ezek. 1:25; Jer 25:30; Joel 3:16–17; Amos 1:2, etc.); and God's voice was heard in the thunder and in the roar of the sea.[1]

The concept appears in Dan 4:31:[2]

- עוד מלתא בפם מלכא קל מן־ שׁמיא נפל לך אמרין נבוכדנצר מלכא מלכותה עדת מנך

- [T]here fell a voice from heaven, saying, O king Nebuchadnezzar, to thee it is spoken; The kingdom is departed from thee (emphasis added).

Talmud

In the period of the Tannaim (c 100 BCE-200 CE) the term bath ḳōl was in very frequent use and was understood to signify not the direct voice of God, which was held to be supersensible, but the echo of the voice (the bath being somewhat arbitrarily taken to express the distinction). The rabbis held that bath ḳōl had been an occasional means of divine communication throughout the whole history of Israel and that since the cessation of the prophetic gift after the First Temple Era it was the sole means of Divine revelation.

It is noteworthy that the rabbinical conception of bath ḳōl sprang up in the period of the decline of Jewish prophecy and flourished in the period of extreme traditionalism. Where the gift of prophecy was believed to be lacking – perhaps even because of this lack – there grew up an inordinate desire for special divine manifestations. Often a voice from heaven was looked for to clear up matters of doubt and even to decide between conflicting interpretations of the law. So strong had this tendency become that Rabbi Joshua (c. 100 CE) felt it to be necessary to oppose it and to insist upon the supremacy and the sufficiency of the written law.

The last nevi'im ("spokespersons", "prophets") mentioned in the Jewish Bible are Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, all of whom lived at the end of the 70-year Babylonian captivity. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 11a) states that nowadays only the "Bath Kol" exists.

New Testament

In the New Testament mention of “a voice from heaven” occurs in the following passages: Matt 3:17; Mark 1:11;[3] Luke 3:22 (at the baptism of Jesus); Matt 17:5; Mark 9:7; Luke 9:35 (at the transfiguration); John 12:28 (shortly before the Passion); Acts 9:4; Acts 22:7; Acts 26:14 (conversion of Paul), and Acts 10:13, Acts 10:15 (instruction of Peter concerning the clean and unclean).

It is clear that we have here to do with a conception of the nature and means of divine revelation that is distinctly inferior to the Biblical view. For even in the Biblical passages where mention is made of the voice from heaven, all that is really essential to the revelation is already present, at least in principle, without the audible voice.[2]

Interpretation

Josephus (Ant., XIII, x, 3) relates that John Hyrcanus (135–104 BCE) heard a voice while offering a burnt sacrifice in the temple, which Josephus expressly interprets as the voice of God.[2]

Christian scholars interpreted Bath Kol as the Jews' replacement for the great prophets when, "after the death of Malachi, the spirit of prophecy wholly ceased in Israel" (taking the name to refer to its being "the daughter" of the main prophetic "voice").[4]

Art

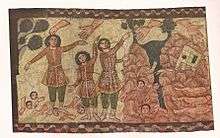

In Jewish art the Bat Ḳol was perhaps often represented by the Hand of God, as in the synagogue of Dura-Europas, which Christian art also adopted for the relevant New Testament scenes.

Literature

Josephus (Ant., XIII, x, 3) relates that John Hyrcanus (135–104 BCE) heard a voice while offering a burnt sacrifice in the temple, which Josephus expressly interprets as the voice of God.[2] According to Hebrew traditions, Metatron − an archangel and God's celestial scribe − is called the "Voice of God".

Other media

The generic term "voice of God" is commonly used in theatrical productions and staging, and refers to any anonymous, disembodied voice used to deliver general messages to the audience. Examples may include speaker introductions, audience directions and performer substitutions.

The origin of the "Voice of God" narration style was most probably in Time Inc's "March of Time"[5] news-radio and news-film series, for which Orson Welles was an occasional voice-over actor, and was subsequently duplicated in Welles' "Citizen Kane"[6] News On The March sequence (the first reel of the film), much to the delight of Henry R. Luce, Time's president.

People called the "Voice of God"

- Mohammed Rafi, Indian playback singing genius.

- James Earl Jones, television, film and voice actor, best known for his role as the voice of Darth Vader in Star Wars.[8]

- Bob Sheppard, public-address announcer for New York Yankees baseball games from 1951 to 2007 and for New York Giants football games from 1956 to 2005[9]

- Don LaFontaine, narrator of many film trailers[10]

- John Facenda, Philadelphia newscaster who narrated several NFL Films Productions from 1966 to 1984[11]

- Morgan Freeman, actor, narrator of films and a portrayer of God in Bruce Almighty and Evan Almighty[12]

- Don Pardo, television personality and former announcer on Saturday Night Live[13]

References

- The Jewish Encyclopedia: BAT ḲOL: Kohler, Kaufmann; Blau, Ludwig. "BAT ḲOL". JewishEncyclopedia.com - The unedited full-text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- This article incorporates text from the International Standard Bible Encyclopediaarticle "Bath Kol", a publication now in the public domain.

- And a voice came from heaven: "You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased."Mark 1:11

- The Old and New Testament connected in the history of the Jews

- Fielding, Raymond. The March of Time, 1935-1951. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978

- Mary Wood. "Citizen Kane and other imitators". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- https://nasirdotcom.wordpress.com/2016/07/04/tributes-to-mohammed-rafi-from-manmohan-desai/

- https://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/james-earl-jones-hopes-his-god-voice-helped-obama-win

- https://www.newsday.com/sports/baseball/yankees/voice-of-god-bob-sheppard-dies-at-99-1.2096118

- https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/03/arts/television/03lafontaine.html

- http://views.washingtonpost.com/theleague/panelists/2009/04/harry-kalas-voice-nfl-films-facenda-schaffer.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/politics/first-draft/2016/02/19/morgan-freeman-hollywoods-voice-of-god-narrates-ad-for-hillary-clinton/

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/08/19/don-pardo-voice-of-saturday-night-live-dead-at-96/

Sources

- This page draws text from 'The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction', Vol. 10, Issue 273, September 15, 1827, a text now in the public domain.

- Humphrey Prideaux, The Old and New Testament connected in the history of the Jews, 1851.

- Thomas de Quincey, Narrative And Miscellaneous Papers, Vol. II.

- Free Prophecy, The Voice of God

This article incorporates text from the International Standard Bible Encyclopediaarticle "Bath Kol", a publication now in the public domain.