Ullr

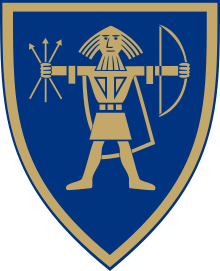

In early Germanic paganism, *Wulþuz ("glory") appears to have been an important concept, perhaps personified as a god, or an epithet of an important god; it is continued in Old Norse tradition as Ullr, a god associated with archery.

Literary tradition

The term wolþu- "glory" (cf. Old English wuldor and the Gothic wulþus), possibly in reference to the god, is attested on the 3rd century Thorsberg chape (as owlþu-), and there are many placenames in Ullr and a related name, Ullinn, but medieval Icelandic sources have only sparse material on the god Ullr. The medieval Norse word was Latinized as Ollerus.

The Icelandic form is Ullur. In the mainland North Germanic languages, the modern form is Ull.

The Old English cognate wuldor means "glory" but is not used as a proper name, although it figures frequently in kennings for the Christian God such as wuldres cyning "king of glory", wuldorfæder "glory-father" or wuldor alwealda "glorious all-ruler".

Epigraphy

The Thorsberg chape (a metal piece belonging to a scabbard found in the Thorsberg moor) bears an Elder Futhark inscription, one of the earliest known altogether, dating to roughly AD 200.

owlþuþewaz / niwajmariz

The first element owlþu, for wolþu-, means "glory", "glorious one", Old Norse Ullr, Old English wuldor. The second element, -þewaz, means "slave, servant". The whole compound is a personal name or title, "servant of the glorious one", "servant/priest of Ullr". Niwajmariz means "well-honored".

Gesta Danorum

In Saxo Grammaticus' 12th century work Gesta Danorum, where gods appear euhemerized, Ollerus is described as a cunning wizard with magical means of transportation:

|

|

When Odin was exiled, Ollerus was chosen to take his place. Ollerus ruled under the name Odin for ten years until the true Odin was called back.

Poetic Edda

Ullr is mentioned in the poem Grímnismál where the homes of individual gods are recounted. The English versions shown here are by Thorpe.

|

|

The name Ýdalir, meaning "yew dales", is not otherwise attested. The yew was an important material in the making of bows, and the word ýr, "yew", is often used metonymically to refer to bows. It seems likely that the name Ýdalir is connected with the idea of Ullr as a bow-god.

Another strophe in Grímnismál also mentions Ullr.

|

|

The strophe is obscure but may refer to some sort of religious ceremony. It seems to indicate Ullr as an important god.

The last reference to Ullr in the Poetic Edda is found in Atlakviða:

|

|

Both Atlakviða and Grímnismál are often considered to be among the oldest extant Eddic poems. It may not be a coincidence that they are the only ones to refer to Ullr. Again we seem to find Ullr associated with some sort of ceremony, this time that of swearing an oath by a ring, a practice associated with Thor in later sources.

Prose Edda

In chapter 31 of Gylfaginning in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, Ullr is referred to as a son of Sif (with a father unrecorded in surviving sources) and as a stepson of Sif's husband; the major Germanic god Thor:

|

|

In Skáldskaparmál, the second part of the Prose Edda, Snorri mentions Ullr again in a discussion of kennings. Snorri informs his readers that Ullr can be called ski-god, bow-god, hunting-god and shield-god. In turn a shield can be called Ullr's ship. Despite these tantalising tidbits Snorri relates no myths about Ullr. It seems likely that he didn't know any, the god having faded from memory.

Skaldic poetry

Snorri's note that a shield can be called Ullr's ship is borne out by surviving skaldic poetry with kennings such as askr Ullar, far Ullar and kjóll Ullar all meaning Ullr's ship and referring to shields. While the origin of this kenning is unknown it could be connected with the identity of Ullr as a ski-god. Early skis, or perhaps sleds, might have been reminiscent of shields. A late Icelandic composition, Laufás-Edda, offers the prosaic explanation that Ullr's ship was called Skjöldr, "Shield".

The name of Ullr is also common in warrior kennings, where it is used as other god names are.

- Ullr brands – Ullr of sword – warrior

- rand-Ullr – shield-Ullr – warrior

- Ullr almsíma – Ullr of bowstring – warrior[3]

Three skaldic poems, Þórsdrápa, Haustlöng and a fragment by Eysteinn Valdason, refer to Thor as Ullr's stepfather, confirming Snorri's information.

Toponymy

Ullr's name appears in several important Norwegian and Swedish place names (but not in Denmark or in Iceland). This indicates that Ullr had at some point a religious importance in Scandinavia that is greater than what is immediately apparent from the scant surviving textual references. It is also probably significant that the placenames referring to this god are often found close to placenames referring to another deity: Njörðr in Sweden and Freyr in Norway.[4] Some of the Norwegian placenames have a variant form, Ullinn. It has been suggested that this is the remnant of a pair of divine twins[5] and further that there may have been a female Ullin, on the model of divine pairs such as Fjörgyn and Fjörgynn.[6] Probably Ullr’s name also can be read in the former Finnish municipality Ullava in Central Osthrobotnia Region.

Norway

- Ullarhváll ("Ullr's hill") - name of an old farm in Oslo and of Ullevaal Stadion

- Ullestad ("Ulle's place") - name of old farm in Voss.

- Ullarnes ("Ullr's headland") - name of an old farm in Rennesøy.

- Ullerøy ("Ullr's island") - name of four old farms in Skjeberg, Spind, Sør-Odal and Vestre Moland.

- Ullern (Ullarvin) ("Ullr's meadow") - name of old farms in Hole, Oslo, Ullensaker, Sør-Odal and Øvre Eiker.

- Ullinsakr ("Ullin's field") - name of two old farms in Hemsedal and Torpa (old church site).

- Ullinshof ("Ullin's temple") - name of three old farms in Nes, Hedmark (old church site), Nes, Akershus and Ullensaker (old church site).

- Ullensvang ("Ullr's field") - name of an old farm in Ullensvang (old church site).

- Ullinsvin ("Ullin's meadow") - name of an old farm in Vågå (old church site).

- Ullsfjorden ("Ullr's Fjord") - fjord in Troms county. Commonly believed to be named after Ullr, although there is some uncertainty.

- Ulvik ("Ullr's bay") - village and fjord in Hordaland county.

(For a possible nickname *Ringir for Ullr see under the name Ringsaker.)

Sweden

- Ulleråker ("Ullr's field") Uppland

- Ultuna ("Ullr's town") Uppland

- Ullared ("Ull's clearing?") Halland

- Ullevi ("Ullr's sanctuary") Västergötland

- Lilla Ullevi, Bro, Stockholm. In 2007/8, excavations in have yielded the remains of a cult site. The site is associated with Ullr based on the toponym Lilla Ullevi ("little shrine of Ullr"). Its most notable feature is an arrangement of rocks, dated to the Vendel Period, in two "wings" with four large post holes. A total of 65 amulet rings have been recovered in the vicinity.[7]

- Ullvi ("Ullr's sanctuary") Västmanland

- Ullene ("Ullr's meadow") Västergötland

- Ullervad ("Ullr's place to wading") Västergötland

- Ullånger ("Ullr's bay") Ångermanland

- Ullen Värmland, Hagfors springsource lake

- Ullbro ("Ulls bridge") Uppland, Enköping

- Ullunda ("Ulls grove") Uppland, Enköping

- Ullstämma ("Ulls meeting") Uppland, Enköping

- Värmullen Värmland, Hagfors

- Ullsberg ("Ull's mountain") Värmland, Hagfors

Modern reception

Viktor Rydberg speculates in his Teutonic Mythology that Ullr was the son of Sif and Egill-Örvandill, half-brother of Svipdagr-Óðr, nephew of Völundr and a cousin of Skaði. His father, Egill, was the greatest archer in the mythology, and Ullr follows in his father's footsteps. Ullr helped Svipdagr-Eiríkr rescue Freyja from the giants. Rydberg also postulates he also ruled over the Vanir when they held Ásgarðr during the war between the Vanir and the Æsir, however Rudolf Simek states "this has no basis in the sources whatsoever". [8]

Ullr is a playable character in the video game Smite.[9]

Within the winter skiing community of Europe the Old Norse god "Ullr" is considered the Guardian Patron Saint of Skiers (German Schutzpatron der Skifahrer). An Ullr medallion or Ullr ski medal, depicting the Scandinavian god Ullr on skis holding a bow and arrow, is widely worn as a talisman by both recreational and professional skiers as well as ski patrols in Europe and elsewhere.

The town of Breckenridge, Colorado hosts a week-long festival called "Ullr Fest" each year in January, featuring numerous events designed to win his favor in an effort to bring snow to the historic ski town. Breck Ullr Fest was first held in 1963.[10]

In the television series "The Almighty Johnsons", Ullr is depicted as a reincarnation of himself, named Mike Johnson, and is played by Tim Balme.[11]

In the game Totally Accurate Battle Simulator, Ullr is a secret unit with the ability to freeze entire armies.

In the book Hammered, third book in The Iron Druid Chronicles, Ullr makes an appearance when the main character and his five man team raid Asgard.

Notes

- "Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, Liber 3, Caput 4". kb.dk.

- "Gylfaginning 23-32". hi.is.

- http://www.hi.is/~eybjorn/ugm/kennings/tvoca.html

- Rudolf Simek, Dictionary of Northern Mythology, tr. Angela Hall, Cambridge / Rochester, New York: Brewer, 1993, ISBN 9780859913690, p. 339.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis; Gelling, Peter (1969). The chariot of the sun: and other rites and symbols of the northern bronze age. Praeger. p. 179.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1990). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books Limited. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-14-194150-9.

- Bäck, Mathias; Hållans Stenholm, Ann-Mari; Ljung, Jan-Åke, Lilla Ullevi - historien om det fridlysta rummet : Vendeltida helgedom, medeltida by och 1600-talsgård : Uppland, Bro socken, Klöv och Lilla Ullevi 1:5, Jursta 3:3, RAÄ 145 Arkeologiska uppdragsverksamheten (UV) rapporter (2008) samla.raa.se. Arkeologiska uppdragsverksamheten (UV) rapporter 2000-2012 M. Bäck, A. Hållans Stenholm, Lilla Ullevi : en unik kultplats, Populär arkeologi. - 0281-014X. ; 2009(27):3, 16-18. A. H. Jakobsson, Cecilia Lindblom, Gard ok Gravfält vid Lilla Ullevi, Rapporter fran Arkeologikonsult 2011:2165.

- Simek, Rudolf (Dec 2010). "The Vanir: An Obituary". Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter. University of Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Dec 2010: 12. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "SMITE". www.smitegame.com. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- "Breckenridge Ullr Fest". Breckenridge Resort Managers. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "The Almighty Johnsons". thealmightyjohnsons.co.nz.

References

- Eysteinn Björnsson (ed.) (2005). Snorra-Edda: Formáli & Gylfaginning : Textar fjögurra meginhandrita.

- Eysteinn Björnsson (2001). Lexicon of Kennings: Domain of Battle.

- Eysteinn Björnsson. Eysteinn Valdason: From a Thor poem.

- Finnur Jónsson (1931). Lexicon Poeticum, "Ullr". S. L. Møllers Bogtrykkeri, København. Entry available online

- Jón Helgason (Ed.). (1955). Eddadigte (3 vols.). Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- Nesten, H. L. (ed.) (1949). Ullensaker - en bygdebok, v. II. Jessheim trykkeri.

- Rydberg, Viktor Undersökningar i Germanisk Mythologi, 2 volumes (1886–1889) Volume 1 (1886), translated as "Teutonic Mythology" (1889), Rasmus B. Anderson. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Reprinted 2001, Elibron Classics. ISBN 1-4021-9391-2. Reprinted 2004, Kessinger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7661-8891-4. Volume 2 (1889), translated as "Viktor Rydberg's Investigations into Germanic Mythology, Part 1: Germanic Mythology. William P. Reaves, iUniverse, 2004, and Part 2: Indo-European Mythology. William P. Reaves, iUniverse, 2008.

- Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, Books I-IX, translated to English by Oliver Elton 1905.

- Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, from the Royal Library in Copenhagen, Danish and Latin.

- Snorri Sturluson ; translated by Jean I. Young (1964). The Prose Edda : Tales from Norse mythology. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Thorpe, Benjamin. (Trans.). (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Froða: The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned. (2 vols.) London: Trübner & Co. 1866. (HTML version available at Northvegr: Lore: Poetic Edda - Thorpe Trans.)

External links

- MyNDIR (My Norse Digital Image Repository) Illustrations of Ullr from manuscripts and early print books. Clicking on the thumbnail will give you the full image and information concerning it.