Tupolev Tu-95

The Tupolev Tu-95 (Russian: Туполев Ту-95; NATO reporting name: "Bear") is a large, four-engine turboprop-powered strategic bomber and missile platform. First flown in 1952, the Tu-95 entered service with the Soviet Union in 1956 and is expected to serve the Russian Aerospace Forces until at least 2040.[1] A development of the bomber for maritime patrol is designated Tu-142, while a passenger airliner derivative was called Tu-114.

| Tu-95 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tu-95MS Bear H RF-94130 off Scotland in 2014 | |

| Role | Strategic heavy bomber |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Tupolev |

| First flight | 12 November 1952 |

| Introduction | 1956 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Aerospace Forces Soviet Air Forces (historical) Soviet Navy (historical) Ukrainian Air Force (historical) |

| Produced | 1952–1993 |

| Number built | 500+ |

| Variants | Tupolev Tu-114 Tupolev Tu-142 Tupolev Tu-95LAL Tupolev Tu-116 |

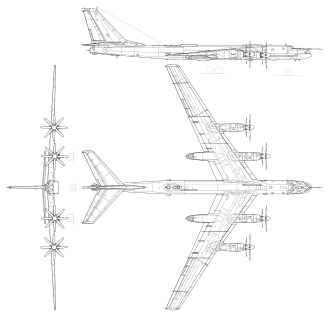

The aircraft has four Kuznetsov NK-12 engines with contra-rotating propellers. It is the only propeller-powered strategic bomber still in operational use today. The Tu-95 is one of the loudest military aircraft, particularly because the tips of the propeller blades move faster than the speed of sound.[2] Its distinctive swept-back wings are set at an angle of 35°. The Tu-95 is unique as a propeller-driven aircraft with swept wings that has been built in large numbers.

Design and development

The design bureau, led by Andrei Tupolev, designed the Soviet Union's first intercontinental bomber, the 1949 Tu-85, a scaled-up version of the Tu-4, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress copy.[3]

A new requirement was issued to both Tupolev and Myasishchev design bureaus in 1950: the proposed bomber had to have an un-refueled range of 8,000 km (4,970 mi)—far enough to threaten key targets in the United States. Other goals included the ability to carry an 11,000 kg (24,200 pounds) load over the target.[4]

Tupolev was faced with selecting a suitable type of powerplant: the Tu-4 showed that piston engines were not powerful enough for such a large aircraft, and the AM-3 jet engines for the proposed T-4 intercontinental jet bomber used too much fuel to give the required range.[5] Turboprop engines were more powerful than piston engines and gave better range than the turbojets available at the time, and gave a top speed between the two. Turboprops were also initially selected for the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress to meet its long range requirement,[6] and for the British long-range transport aircraft, the Saunders-Roe Princess, the Bristol Brabazon and the Bristol Britannia.

Tupolev proposed a turboprop installation and Tu-95 design with this configuration was officially approved by the government on 11 July 1951. It used four Kuznetsov[7] coupled turboprops, each fitted with two contra-rotating propellers with four blades each, with a nominal 8,948 kW (12,000 effective shaft horse power [eshp]) power rating. The engine, advanced for its time, was designed by a German team of ex-Junkers prisoner-engineers under Ferdinand Brandner. The fuselage was conventional with a mid-mounted wing with 35 degrees of sweep, an angle which ensured that the main wing spar passed through the fuselage in front of the bomb bay. Retractable tricycle landing gear was fitted, with all three gear strut units retracting rearwards, with the main gear units retracting rearwards into extensions of the inner engine nacelles.[4]

The Tu-95/I, with 2TV-2F engines, first flew in November 1952 with test pilot Alexey Perelet at the controls.[8] After six months of test flights this aircraft suffered a propeller gearbox failure and crashed, killing Perelet. The second aircraft, Tu-95/II used four 12,000 eshp Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprops which proved more reliable than the coupled 2TV-2F. After a successful flight testing phase, series production of the Tu-95 started in January 1956.[7]

For a long time, the Tu-95 was known to U.S./NATO intelligence as the Tu-20. While this was the original Soviet Air Force designation for the aircraft, by the time it was being supplied to operational units it was already better known under the Tu-95 designation used internally by Tupolev, and the Tu-20 designation quickly fell out of use in the USSR. Since the Tu-20 designation was used on many documents acquired by U.S. intelligence agents, the name continued to be used outside the Soviet Union.[4]

Initially the United States Department of Defense evaluated the Tu-95 as having a maximum speed of 644 km/h (400 mph) with a range of 12,500 km (7,800 mi).[9] These numbers had to be revised upward numerous times.[4]

Like its American counterpart, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, the Tu-95 has continued to operate in the Russian Air Force while several subsequent iterations of bomber design have come and gone. Part of the reason for this longevity was its suitability, like the B-52, for modification to different missions. Whereas the Tu-95 was originally intended to drop free-falling nuclear weapons, it was subsequently modified to perform a wide range of roles, such as the deployment of cruise missiles, maritime patrol (Tu-142), and even civilian airliner (Tu-114). An AWACS platform (Tu-126) was developed from the Tu-114. An icon of the Cold War, the Tu-95 has served, not only as a weapons platform, but as a symbol of Soviet and later Russian national prestige. Russia's air force has received the first examples of a number of modernised strategic bombers in Tu-95MSs following upgrade work. Enhancements have been confined to the bomber's electronic weapons and targeting systems.[10] Modernization of the first batch was completed in March 2020.[11]

Tu-116

Designed as a stopgap in case the Tu-114A was not finished on time, two Tu-95 bombers were fitted with passenger compartments. Both aircraft had the same layout: office space, a passenger cabin consisting of 2 sections which could each accommodate 20 people in VIP seating, and the rest of the 70 m³ cabin configured as a normal airliner. Both aircraft were eventually used as crew ferries by the various Tu-95 squadrons.[12] One of these machines is preserved at Ulyanovsk Central Airport.

Modernization

Currently ongoing modernization of the Russia's Tu-95MS bombers is aimed primarily on the aircraft armament, namely adaptation of the new Kh-101/102 stealth cruise missile. The modernization includes installation of four underwing pylons for up to 8 Kh-101/102 cruise missiles as well as adjusting aircraft's main weapons bay for cruise missiles of size the Kh-101/102 (7.5 meters).[13] Besides, the modernized Tu-95MS aircraft use radio-radar equipment and target-acquiring/navigation system based on GLONASS.[14] The first Tu-95 modernized to carry the Kh-101/102 missiles was the Tu-95MS Saratov, rolled out at the Beriev aircraft plant in Taganrog in early 2015.[13] It was transferred to the Russian Air Force in March 2015.[15] Since 2015, the serial modernization is carried out also by the Aviakor aircraft plant in Samara at a rate of three aircraft per year.[13][16] The first Tu-95 modernized by the Aviakor was the Tu-95MS Dubna, transferred to the Russian Air Force on 18 November 2015.[17][14] In the future, Tu-95MSs are to be upgraded also with the new Kuznetsov NK-12MPM turboprop engines for increased flight range, combat load and reduced noise and vibrations[18] and with the SVP-24 sighting and computing system from the Russian company Gefest & T.[19]

More complex modernization of the Tu-95MS16 bombers, known as "Tu-95MSM", is currently under development by Tupolev under a contract issued by the Russian Defence Ministry on 23 December 2009. This modernization is to include installation of the new Novella-NV1.021 radar, instead of the current Obzor-MS, installation of the SOI-021 information display system and the Meteor-NM2 airborne defense complex. In addition, the aircraft modernized to the "MSM" variant will be equipped with the upgraded Kuznetsov NK-12MPM turboprop engines.[13][18] A contract for first modernized aircraft was signed in February 2018 with first flight scheduled for end of 2019.[20]

Operational history

Soviet Union

The Tu-95RT variant in particular was a veritable icon of the Cold War as it performed a maritime surveillance and targeting mission for other aircraft, surface ships and submarines. It was identifiable by a large bulge under the fuselage, which reportedly housed a radar antenna that was used to search for and detect surface ships.[21]

A series of nuclear surface tests were carried out by the Soviet Union in the early to mid 1960s. On October 30, 1961 a modified Tu-95 carried and dropped the AN602 device named Tsar Bomba, which was the most powerful thermonuclear device ever detonated.[22] Video footage of that particular test exists[23] since the event was filmed for documentation purposes. The footage shows the specially adapted Tu-95V plane – painted with anti-flash white[24] on its ventral surfaces – taking off carrying the bomb, in-flight scenes of the interior and exterior of the aircraft, and the detonation. The bomb was attached underneath the aircraft, which carried the weapon semi-externally since it could not be carried inside a standard Tu-95's bomb-bay, similar to the way the B.1 Special version of the Avro Lancaster did with the ten-tonne Grand Slam "earthquake bomb". Along with the Tsar Bomba, the Tu-95 proved to be a versatile bomber that would deliver the RDS-4 Tatyana (a fission bomb with a yield of forty-two kilotons), RDS-6S thermonuclear bomb, the RDS-37 2.9-megaton thermonuclear bomb, and the RP-30-32 200-kiloton bomb.[25]

The early versions of this bomber lacked comfort for their crews. They had a dank and dingy interior and there was neither a toilet nor a galley in the aircraft.[25] Though the living conditions on the bomber were unsatisfactory, the crews would often take two 10-hour mission trips a week to ensure combat readiness. This gave an annual total of around 1,200 flight hours.[26]

The bomber had the best crews available due to the nature of their mission. They would undertake frequent missions into the Arctic to practice transpolar strikes against the United States. Unlike their American counterparts they never flew their missions carrying nuclear weapons. This hindered their mission readiness due to the fact that live ammunition had to come from special bunkers on the bases and loaded into the aircraft from the servicing trench below the bomb bay, a process that could take two hours.[27]

Russia

In 1992, newly independent Kazakhstan began returning the Tu-95 aircraft of the 79th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division at Dolon air base to the Russian Federation.[28] The bombers joined those already at the Far Eastern Ukrainka air base.[29]

On 17 August 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia was resuming the strategic aviation flights stopped in 1991, sending its bombers on long-range patrols.[30][31]

NATO fighters are often sent to intercept and escort Tu-95s as they perform their missions along the periphery of NATO airspace, often in close proximity to each other.[32][33][34][35]

Russian Tu-95s reportedly took part in a naval exercise off the coasts of France and Spain in January 2008, alongside Tu-22M3 strategic bombers and A-50 airborne early-warning aircraft.[36]

During the Russian Stability 2008 military exercise in October 2008, Tu-95MS aircraft fired live air-launched cruise missiles for the first time since 1984. The long range of the Kh-55 cruise missile means the Tu-95MS can once again serve as a strategic weapons system.[37]

In July 2010, two Russian Tu-95MS strategic bombers set a world record for a non-stop flight for an aircraft in the class, when they spent more than 43 hours in the air. The bombers flew through the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific oceans and the Sea of Japan, covering in total more than 30,000 km with four mid-air refuelings. The main task was to check the performance of the aircraft during such a long flight, in particular monitoring the engines and other systems.[38]

On 17 November 2015, Tu-95s had their combat debut, being employed for the first time in long-range airstrikes as part of the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[39][40]

On 17 November 2016, modernized Tu-95MS strategic bombers performed their first combat deployment, launching the Kh-101 cruise missiles on several militant positions in Syria.[41]

On 5 December 2017, two Tu-95MS strategic bombers and two Il-76MD transport aircraft landed for the first time at the Biak Air Base in Indonesia. The bombers covered more than 7,000 km with mid-air refueling before landing at the air base. In a course of their visit, the Tu-95's crews conducted their first patrol flights over the southern Pacific, staying airborne for more than eight hours.[42][43][44]

Incidents

- In 1968 two planes were lost over the Black Sea during a training flight. Both planes fell into the sea, one of them was to be salvaged later, and only one crew member out of 18 survived. These planes had been operating from AFB Uzyn (Ukraine).

- On June 8, 2015 a Tu-95 ran off a runway at the Ukrainka bomber base and caught fire during take-off in the far eastern Amur region. As a result, one crew member was killed.[45][46]

- On July 14, 2015 it was reported that a Tu-95MS had crashed outside Khabarovsk, killing two of seven crew members.[47]

Variants

_(7985693728).jpg)

- Tu-95/1

- The first prototype powered by Kuznetsov 2TV-2F coupled turboprop engines.

- Tu-95/2

- The second prototype powered by Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprops.

- Tu-95

- Basic variant of the long-range strategic bomber and the only model of the aircraft never fitted with a nose refuelling probe. Known to NATO as the Bear-A.

- Tu-95K

- Experimental version for air-dropping a MiG-19 SM-20 jet aircraft.

- Tu-95K22

- Conversions of the older Bear bombers, reconfigured to carry the Raduga Kh-22 missile and incorporating modern avionics. Known to NATO as the Bear-G.

- Tu-95K/Tu-95KD

- Designed to carry the Kh-20 air-to-surface missile. The Tu-95KD aircraft were the first to be outfitted with nose probes. Known to NATO as the Bear-B.

- Tu-95KM

- Modified and upgraded versions of the Tu-95K, most notable for their enhanced reconnaissance systems. These were in turn converted into the Bear-G configuration. Known to NATO as the Bear-C.

- Tu-95LAL

- Experimental nuclear-powered aircraft project.

- Tu-95M

- Modification of the serial Tu-95 with the NK-12M engines. 19 were built.

- Tu-95M-55

- Missile carrier.

- Tu-95MR

- Bear-A modified for photo-reconnaissance and produced for Naval Aviation. Known to NATO as the Bear-E.

- Tu-95MS/Tu-95MS6/Tu-95MS16

- Completely new cruise missile carrier platform based on the Tu-142 airframe. This variant became the launch platform of the Raduga Kh-55 cruise missile and put into serial production in 1981.[48] Known to NATO as the Bear-H and was referred to by the U.S. military as a Tu-142 for some time in the 1980s before its true designation became known. Currently being modernized to carry the Kh-101/102 stealth cruise missiles. 21 aircraft have been modernized as of April 2019.[49][50][51][52][53][54] In 2019, 5 modernized Tu-95MS aircraft have joined the Fleet.[55]

- Tu-95MS6

- Capable of carrying six Kh-55, Kh-55SM or Kh-555 cruise missiles on a rotary launcher in the aircraft's weapons bay. 32 were built.[56]

- Tu-95MS16

- Fitted with four underwing pylons in addition to the rotary launcher in the fuselage, giving a maximum load of 16 Kh-55s or 14 Kh-55SMs. 56 were built.[56]

- Tu-95MSM

- Modernization of the "Tu-95MS16" bombers, equipped with the new Novella-NV1.021 radar, SOI-021 information display system, Meteor-NM2 airborne defense complex and upgraded Kuznetsov NK-12MPM turboprop engines. First flight scheduled for end of 2019.[20]

- Tu-95N

- Experimental version for air-dropping an RS ramjet powered aircraft.

- Tu-95RTs

- Variant of the basic Bear-A configuration, redesigned for maritime reconnaissance and targeting as well as electronic intelligence for service in the Soviet Naval Aviation. Known to NATO as the Bear-D.

- Tu-95U

- Training variant, modified from surviving Bear-As but now all have been retired. Known to NATO as the Bear-T.

- Tu-95V

- Special carrier aircraft to test-drop the largest thermonuclear weapon ever designed, the Tsar Bomba.

- Tu-96

- Long-range intercontinental high-altitude strategic bomber prototype, designed to climb up to 16,000–17,000 m.[57] It was a high-altitude version of the Tupolev Tu-95 aircraft with high-altitude augmented turboprop TV-16 engines and with a new, enlarged-area wing. Plant tests of the aircraft were performed with non-high altitude TV-12 engines in 1955–1956.[58]

Tu-95 derivatives

- Tu-114

- Airliner derivative of Tu-95.

- Tu-116

- Tu-95 fitted with passenger cabins as a stop-gap while the Tu-114 was being developed. 2 were converted.[59]

- Tu-126

- AEW&C derivative of Tu-114, itself derived from the Tu-95.

- Tu-142

- Maritime reconnaissance/anti-submarine warfare derivative of Tu-95. Known to NATO as the Bear-F.

Several other modifications of the basic Tu-95/Tu-142 airframe have existed, but these were largely unrecognized by Western intelligence or else never reached operational status within the Soviet military.

Operators

- Russian Aerospace Forces

- Russian Air Force – 55 Tu-95MS are in service as of 2020.[60][61]

- 6950th Guards Air Base – Engels-2 (air base), Saratov Oblast

- 184th Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 6952nd Air Base – Ukrainka (air base), Amur Oblast

- 182nd Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 79th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 43rd Center for Combat Application and Training of Aircrew for Long Range Aviation – Dyagilevo (air base), Ryazan Oblast[62][63]

- 2nd Instructor Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 6950th Guards Air Base – Engels-2 (air base), Saratov Oblast

- Russian Air Force – 55 Tu-95MS are in service as of 2020.[60][61]

Former operators

- Soviet Air Forces – aircraft were transferred to Russian and Ukrainian Air Forces after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

- 106th Heavy Bomber Air Division – the first Tu-95s division formed in 1956.[64] The division commander was twice-Hero of the Soviet Union A. G. Molodchi.[65]

- 1006th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment – Uzyn Air Base, Kiev Oblast, Ukrainian SSR

- 409th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment – Uzyn Air Base, Kiev Oblast, Ukrainian SSR

- 182nd Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment – Mozdok, Severo-Osetinskaya ASSR

- 79th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division – Dolon (air base), Semipalatinsk Oblast, Kazakh SSR[66]

- 1223rd Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 1226th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 73rd Heavy Bomber Aviation Division – Ukrainka (air base), Amur Oblast, Russian SFSR[67]

- 40th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment – united with the 182nd TBAP in 1998 at the Ukrainka Air Base

- 79th Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment

- 106th Heavy Bomber Air Division – the first Tu-95s division formed in 1956.[64] The division commander was twice-Hero of the Soviet Union A. G. Molodchi.[65]

- Soviet Naval Aviation

- 392nd Separate Long-Range Reconnaissance Aviation Regiment – Kipelovo, Vologda Oblast, Russian SFSR[68]

- 304th Separate Long-Range Reconnaissance Aviation Regiment – Khorol Airfield, Primorsky Krai, Russian SFSR[68]

- 169th Independent Guards Mixed Aviation Regiment – Cam Ranh Base, Khánh Hòa Province, Vietnam[69]

- Ukrainian Air Force – inherited 23–29 Tu-95MS aircraft after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and subsequently handed 3 Tu-95MS and 581 Kh-55 cruise missiles to Russia as exchange for gas debt relief in 2000; the remainder were scrapped under the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction agreement led by the US.[70]

- 106th Heavy Bomber Air Division – Uzyn Air Base, Kiev Oblast

- 1006th Heavy Bomber Regiment

- 106th Heavy Bomber Air Division – Uzyn Air Base, Kiev Oblast

- Mykolaiv Aircraft Repair Plant – 2 Tu-95MS converted to ecological reconnaissance aircraft in storage, before they were sold for scrapping in 2013.[71][72]

- Bila Tserkva Aircraft Repair Plant – 5 Russian Tu-95s scrapped at the plant, after an agreement between the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and the Government of Russia.[73]

- 1 Tu-95MS in the Museum of Long Range Aviation in Poltava[70][74] and 1 Tu-95 in Mykolaiv Oblast.[70][75]

Specifications (Tu-95MS)

Data from Combat Aircraft since 1945[76]

General characteristics

- Crew: 6-7; pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer, communications system operator, navigator, tail gunner plus sometimes another navigator.[77]

- Length: 46.2 m (151 ft 7 in)

- Wingspan: 50.1 m (164 ft 4 in)

- Height: 12.12 m (39 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 310 m2 (3,300 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 90,000 kg (198,416 lb)

- Gross weight: 171,000 kg (376,990 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 188,000 kg (414,469 lb)

- Powerplant: 4 × Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprop engines 15,000 PS (15,000 hp; 11,000 kW)

- Propellers: 8-bladed contra-rotating fully-feathering constant-speed propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 830 km/h (520 mph, 450 kn)

- Cruise speed: 550 km/h (340 mph, 300 kn)

- Range: 15,000 km (9,300 mi, 8,100 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 13,716 m (45,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 10 m/s (2,000 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 606 kg/m2 (124 lb/sq ft)

- Power/mass: 0.235 kW/kg (0.143 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns: 1 or 2 × 23 mm AM-23 autocannon in tail turret

- Missiles: Up to 15,000 kg (33,000 lb), including the Kh-20, Kh-22, and Kh-55/101/102, or 8 Kh-101/102 cruise missiles mounted on underwing pylons.[14]

See also

Related development

- Tupolev Tu-114

- Tupolev Tu-119

- Tupolev Tu-126

- Tupolev Tu-142

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Convair B-36

- Boeing XB-55

- Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

- Myasishchev M-4 Molot

- Xian H-6K

Related lists

References

- Kramnik, Ilya (19 July 2007). "Оружие: Возвращение летающего медведя" [Weapons: The return of the flying bear]. Lenta.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- "Russian Bear is back". Russia Today via youtube.com. 24 September 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "Tu-4 "Bull"". Monino Aviation. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Russia Air Force Handbook, Volume 1 Strategic Information and Weapon Systems. Washington DC: International Business Publications, USA, February 7, 2007 (updated 2011). pp. 157–9. ISBN 1-4330-4115-4.

- "Tupolev Tu-95 Bear". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015059171325;view=1up;seq=3 p.40

- Sobolev, D.A.; Khazanov, D.B. "Creation of the TV-2 (NK-12) turboprop engine". airpages.ru. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- "Ту-95МС" [Tu-95MS]. Tupolev (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "Tu-20/95/142 Bear: The fastest prop-driven aircraft." Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine Aviation.ru. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- Perry, Dominic (19 December 2014). "Russian air force takes first modernised Tupolev bombers". Flightglobal. London. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- http://www.airrecognition.com/index.php/news/defense-aviation-news/2020/march/6111-tupolev-completes-upgrade-of-tu-95ms-strategic-bombers.html

- "Tupolev Tu-116". Aviastar. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- "Модернизация российских стратегических бомбардировщиков". bmpd.livejournal.com. 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Russia's Tu-95 Bomber Upgraded to Carry New Nuclear-Tipped Missiles". Sputnik (news agency). 21 November 2015. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Модернизированный Ту-95МС в Энгельсе". bmpd.livejournal.com. 7 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ""Авиакор" возвращается к работам по стратегическим бомбардировщикам Ту-95МС". bmpd.livejournal.com. 22 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Модернизированный бомбардировщик Ту-95МС "Дубна"". bmpd.livejournal.com. 20 November 2015. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "New engines to boost Tu-95MS strategic bombers' flight range". TASS. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Новые возможности Ту-95МС с системами управления от "Гефеста"". bmpd.livejournal.com. 29 June 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Контракт на создание глубоко модернизированного стратегического бомбардировщика Ту-95МСМ". bmpd.livejournal.com. 15 August 2018. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Tupolev Tu-95RT "Bear D"". Archived from the original on 2010-11-05. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- " Big Ivan, The Tsar Bomba ("King of Bombs"): The World's Largest Nuclear Weapon." Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine nuclearweaponarchive.org, 3 September 2007. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- "RDS 202: Tsar Bomb, The Biggest Bomb Ever". Youtube. 17 July 2009. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "RDS 202: Tsar Bomb, The Biggest Bomb Ever". Youtube. 17 July 2009. Event occurs at 1:15 to 1:50. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Zaloga, Steve (17 February 2002). The Kremlin's Nuclear Sword: The Rise and Fall of Russia's Strategic Nuclear Forces. p. 29.

- Semyonov. Raketno-Kosmicheskaya korporatsia Energia. p. 131.

- Prooskov, N. (14 July 1997). Reserves of Combat Readiness: The RVSN.

- "All Strategic Bombers Out Of Kazakhstan; Talks On Those In Ukraine." RFE/RL News Briefs, Vol. 3, No. 9, 21–25 February 1994, via Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- Bukharin et al. 2004, p. 385.

- "Russia orders long-range bomber patrols". USA Today. 17 August 2007. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Russia Resumes Patrols by Nuclear Bombers". The New York Times. 17 August 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "UK jets shadow Russian bombers." Archived 2008-09-25 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 6 July 2007. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- "NORAD downplays Russian bomber interception". Archived 2010-08-28 at the Wayback Machine CBC, 25 August 2010. Retrieved: 6 September 2010.

- Lilley, Brian. "Canadian jets repel Russian bombers". Archived 2010-07-31 at the Wayback Machine Calgary Sun, 30 July 2010.

- "Portugal scrambles jets again to intercept Russian bombers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Halpin, Tony. "RAF alert as Russia stages huge naval exercise in Bay of Biscay." Archived 2008-02-14 at the Wayback Machine The Times, 17 August 2007. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- "Russia revives Cold War aircraft." Archived 2008-11-03 at the Wayback Machine Washington Times, 30 October 2008. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- "Рекорд Ту-95МС: "медведи" провели в воздухе более сорока часов". vesti.ru. 30 July 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Oliphant, Roland; Akkoc, Raziye; Steafel, Eleanor (17 November 2015). "Paris attacks: Cameron to make case for Syria military action as EU troops could be sent to France – latest news". The Daily Telegraph. Online. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Russia's Bombers Tu-160, Tu-95MS Go Through Baptism of Fire in Syria". Sputnik. 18 November 2015. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "Russia's Tupolev-95MSM bomber delivers first-ever strike on mission to Syria". tass.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Russian aircraft make a flight from Amur region to Indonesia within international visit". Russian Defence Ministry. 5 December 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Nuclear-capable Russian Tu-95 bombers in 1st-ever Pacific patrol from Indonesia (VIDEO)". rt.com. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Australian air force put on alert after Russian long-range bombers headed south". The Guardian. 30 December 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Russia Grounds 2nd Fighter Jet Fleet Amid String of Catastrophes". The Moscow Times. 6 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Two Pilots Killed In Russian Tu-95 Bomber Crash". DefenseNews. 14 July 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Russian bomber crashes in the Far East, kills 2" Archived 2015-07-14 at the Wayback Machine 14 July 2015 |Retrieved:14 July 2015

- "Военная авиация — Туполев". tupolev.ru. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "ОАК передала Минобороны РФ очередной стратегический ракетоносец Ту-95МС – Еженедельник "Военно-промышленный курьер"". vpk-news.ru. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "ПАО "Туполев" передало Министерству обороны РФ модернизированный стратегический ракетоносец Ту-95МС — Туполев". tupolev.ru. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Компания "Туполев" продолжает работы по модернизации ракетоносцев Ту-95МС – Еженедельник "Военно-промышленный курьер"". vpk-news.ru. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Tupolev hands over upgraded Tu-160M, Tu-95MSM strategic bombers". www.airrecognition.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Russian strategic Tu-160 bomber test-fires 12 missiles". TASS. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-04-20. Retrieved 2019-04-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://eng.mil.ru/en/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12269606@egNews

- Mladenov Air International August 2015, pp. 43, 45.

- "Стратегический бомбардировщик Ту-96. - Российская авиация". Xn--80aafy5bs.xn--p1ai. 2015-10-03. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- "Tu-96." Archived 2008-03-13 at the Wayback Machine globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- Duffy and Kandalov 1996, pp. 131–132.

- The Military Balance 2017, p.217

- http://russianforces.org/aviation/

- "43rd Center for Combat Employment and Retraining of Personnel DA". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "43rd Center for Combat Application and Training of Aircrew for Long Range Aviation". vitalykuzmin.net. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "106th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division im. 60th anniversary SSSR". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "SSM" manuscript from Yahoo TO&E group

- "79th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "73rd Heavy Bomber Aviation Division". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Авиация ВМФ". airbase.ru. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "169th Guards Roslavlskiy Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Ukraine Bomber Decommissioning and Transfer Chronology" (PDF). Nuclear Threat Initiative. April 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Во времена Лебедева чиновники Минобороны продали два самолета как лом" [Once Lebedev headed Ministry of Defence, its officials sold two aircraft as scrap] (in Russian). www.pravda.com.ua. 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Головною військовою прокуратурою викрито факт продажу військових літаків за ціною металобрухту" [The Main Military Prosecutor's Office disclosed the fact of selling military aircraft at the price of scrap metal] (in Ukrainian). General Prosecutor's Office of Ukraine. 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Российские Ту-95 будут ликвидировать в Белой Церкви". zavtra.com.ua. 22 September 2004. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Музей дальней авиации, Полтава" [Museum of long-range aviation, Poltava] (in Russian). Doroga.ua. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- "51 - Tupolev Tu-95 Bear - Ukraine - Air Force - Simon De Rudder". JetPhotos. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Wilson 2000, p. 137.

- "Tu-95 Bear Strategic Bomber." Archived 2010-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Airforce-Technology.com. Retrieved: 20 January 2011.

- Bibliography

- Bukharin, Oleg, Pavel L. Podvig and Frank von Hippel. Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. Boston: MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-262-66181-2.

- Duffy, Paul and Andrei Kandalov. Tupolev: The Man and His Aircraft. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife, 1996. ISBN 978-1-85310-728-3.

- Eden, Paul (editor). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1-904687-84-9.

- Gordon, Yefim and Peter Davidson. Tupolev Tu-95 Bear. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58007-102-4.

- Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey. Flight: 100 Years of Aviation. Harlow, Essex: DK Adult, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7566-1902-2.

- Mladenov, Alexander. "Still Going Strong". Air International. Vol. 89, No. 2, August 2015. pp. 40–47. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-1-875671-50-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tupolev Tu-95. |