Tsawwassen First Nation

The Tsawwassen First Nation (Halkomelem: sc̓əwaθən məsteyəxʷ, pronounced [st͡sʼəwaθən məstejəxʷ]) is a First Nations government whose lands are located in the Greater Vancouver area of the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada, adjacent to the South Arm of the Fraser River and the Tsawwassen Ferry Terminal and just north of the international boundary with the United States at Point Roberts, Washington. Tsawwassen First Nation lists its membership at approximately 490 people, about half of whom live on the reserve.[2]

Tsawwassen sc̓əwaθən məsteyəxʷ | |

|---|---|

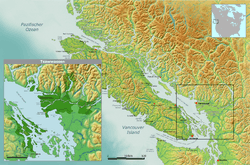

Tsawwassen Lands | |

Traditional Tsawwassen tribal territory | |

| First Nation | Tsawwassen |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Location | Greater Vancouver |

| Government | |

| • Type | Band |

| • Chief | Ken Baird |

| • Affiliation: | Naut'sa mawt Tribal Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.9 km2 (1.1 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 358 estimated |

| Ethnic groups | Coast Salish |

| Languages | Halkomelem (hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓), English |

History

The oldest finds in the area of Tsawwassen First Nation settled by means of radiocarbon dated to about 2260 BC. Other sites such as Whalen Farm and Beach Grove dating back to the presence of Tsawwassen at least until the time of 400-200 BC. The traditional Tsawwassen area ranged in the north east to the area around Pitt Lake, Pitt River to Pitt Meadows down to where the water in the Fraser River flows. It included Burns Bog and parts of New Westminster. From Sea Island to Galiano Island and joined Salt Spring, Pender and Saturna Island. North Eastwards came the Point Roberts Peninsula added, then the area around the Serpentine and Nicomekl River. Like most First Nations people of the West Coast the Tsawwassen lived in family groups and inhabited longhouses. They carved no totem poles but ornate house posts, masks, tools with carvings etc. Also they processed cedar fibers and goat hair into dresses and headgear. Also, the wooden building material, firewood, canoes and dresses. Using tidal traps, fishing, nets and harpoons they hunted fish, especially salmon. They also harvested oysters, crabs and other sea creatures. The salmon was considered a supernatural being, and therefore had to be hunted and eaten in a very particular way. The remains were returned to the sea in a private ceremony. Numerous species of birds were on the menu, such as ducks, loons, to seals and sea lions. Land mammals such as moose, deer, black bear and beaver were hunted seasonally. Also Camassia, Cranberries and medicinal plants were harvested, also traded and exchanged.

Reserves, Loss of land

In 1851, the last frontier settlements in the wake of the border treaty of 1846 between the United States and Great Britain took place. A portion of the Tsawwassen Territory was now in Point Roberts in the U.S. state of Washington. In 1858 the first cross-country road was built in British Columbia from Tsawwassen Beach to Fort Langley. In 1859, it was followed by the first inner-city street the "North Road" between Burnaby and Coquitlam. In 1871, a tiny reserve was assigned to the Tsawwassen peoples, which was enlarged in 1874 to 490 acres. Today, it covers 717 acres or 290 hectares. In 1914, chief Harry Joe sent a petition to the McKenna McBride Commission, with a request for review of reservations. The petition was dismissed. Nevertheless, young Tsawwassen First Nation peoples joined the Canadian Military in the First and Second World Wars.

In 1958, the B.C. provincial government built the BC Ferries terminal in Tsawwassen for their ferries. For this purpose, a Tsawwassen First Nation long house was demolished. When the terminal was enlarged in 1973, 1976, and 1991, there were no consultations with the Tsawwassen peoples.

The Tsawwassen First Nation is a member government of the Naut'sa mawt Tribal Council.

Treaty and land claims negotiations

The Tsawwassen, a Coast Salish people, are one of the few British Columbia First Nations to come to the end of the BC Treaty Process, the others being the Nisga'a, the Temexw Treaty Association and the Lheidl T'enneh First Nation. The treaty deal would have allowed for the expansion of the Roberts Bank Superport and the employment of band members in the expanded facility, but was criticized by some as a sell-out, as the negotiated settlement modified and defined TFN's Aboriginal rights. The Treaty was ratified by Tsawwassen members in July 2007 and expanded the size of the Tsawwassen reserve by 400 hectares, offered a cash settlement of $16 million and $36 million in program funding, re-established TFN's right to self-govern, and reserved a portion of the Fraser River salmon catch to the Tsawwassen. In return, the Tsawwassen would abandon other land claims and would eventually pay taxes.[3] On April 3, 2009, after 14 years of negotiations, the Tsawwassen First Nation implemented the Final Agreement and became self-governing. In 2009, the first election of the new Legislature was called as the existing Indian Act was replaced.[4] Tsawwassen First Nation then also became the first First Nation to become a full member of the Metro Vancouver regional district (now Metro Vancouver).[5]

In January 2012, a "mega-mall" project was approved by the Tsawwassen First Nation, with 43 percent of the eligible voters taking part. Of that 43 percent who voted, 97 percent were in favor of the project. The mall is expected to create jobs and stimulate tourism for the community. The resulting Tsawwassen Mills mall, built by Ivanhoé Cambridge, opened on October 5, 2016.[6]

See also

- Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

- Musqueam First Nation

- Kwantlen First Nation

- Lummi

- Semiahmoo First Nation

- Halkomelem (language)

- North Straits Salish

- Sto:lo

References

- "Factbook" (PDF). Tsawwassen First Nation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

We are the people of the Tsawwassen First Nation. Our 290-hectare (717 acre) reserve is located at Roberts Bank in Delta, on the southern Strait of Georgia near the Canada – U.S. border.

- Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications. "Tsawwassen Final Agreement: General Overview". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Mickleburgh, Rod (July 26, 2007). "Tsawwassen band backs historic urban treaty". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "TFN History and Timeline | Tsawwassen First Nation". tsawwassenfirstnation.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- "TFN Vision & Mandate | Tsawwassen First Nation". tsawwassenfirstnation.com. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- "Tsawwassen First Nation votes for mega-mall". The Globe and Mail. January 19, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2016.