Times Square Ball

The Times Square Ball is a time ball located in New York City's Times Square. Located on the roof of One Times Square, the ball is a prominent part of a New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square commonly referred to as the ball drop, where the ball descends down a specially designed flagpole, beginning at 11:59:00 p.m. ET, and resting at midnight to signal the start of the new year. In recent years, the festivities have been preceded by live entertainment, including performances by musicians.

| Times Square Ball Drop | |

|---|---|

| |

The ball resting atop One Times Square in 2011 | |

| Genre | New Year's Eve event |

| Date(s) | December 31 – January 1 |

| Begins | 6:00 p.m. EST |

| Ends | 12:15 a.m |

| Frequency | Annually |

| Location(s) | Times Square, New York City |

| Inaugurated | 1907 |

| Founder | Adolph Ochs |

| Organized by | Times Square Alliance Countdown Entertainment |

| Website | timessquareball |

The event was first organized by Adolph Ochs, owner of The New York Times newspaper, as a successor to a series of New Year's Eve fireworks displays he held at the building to promote its status as the new headquarters of the Times, while the ball itself was designed by Artkraft Strauss. First held on December 31, 1907, to welcome 1908, the ball drop has been held annually since, except in 1942 and 1943 in observance of wartime blackouts.

The ball's design has been updated over the years to reflect improvements in lighting technology; the ball was initially constructed from wood and iron, and lit with 100 incandescent light bulbs. The current incarnation features a computerized LED lighting system and an outer surface consisting of triangular crystal panels. These panels contain inscriptions representing a yearly theme. Since 2009, the current ball has been displayed atop on Times Square year-round, while the original, smaller version of the current ball that was used in 2008 has been on display inside the Times Square visitor's center.

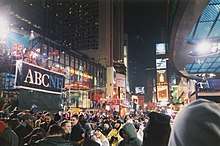

The event is organized by the Times Square Alliance and Countdown Entertainment, a company led by Jeff Strauss,[1] and is among the most notable New Year's celebrations internationally: it is attended by at least 1 million spectators yearly, and is nationally televised as part of New Year's Eve specials broadcast by a number of networks and cable channels.[2] The prevalence of the Times Square ball drop has inspired similar "drops" at other local New Year's Eve events across the country; while some use balls, some instead drop objects that represent local culture or history.

Events

Event organization

.jpg)

To facilitate the arrival of attendees, Times Square is closed to traffic beginning in the late afternoon on New Year's Eve. The square is then divided into different viewing sections referred to as "pens", into which attendees are directed sequentially upon arrival.[3][4] Security is strictly enforced by the New York City Police Department (NYPD), even more so since the 2001–2002 edition in the wake of the September 11 attacks. Attendees are required to pass through security checkpoints before they are assigned a pen, and are prohibited from bringing backpacks or alcohol to the event.[4]

Security was increased further for 2017–18 edition due to recent incidents such as the truck attack in New York on October 31, and the 2017 Las Vegas shooting; these included additional patrols of Times Square hotels, rooftop patrol squads and counter-snipers, and the installation of reflective markers on buildings to help officers identify the location of elevated shooters.[5] For 2018–19, the NYPD announced its intent to use a camera-equipped quadcopter to augment the over 1,200 fixed cameras monitoring Times Square, but it was left grounded due to the rainy weather.[6]

Festivities

Festivities formally begin in the early evening, with the 20 second "6 Hours to Go" countdown followed by the raising of the ball at 6:00 p.m. ET where a guest turns on a switch to light the ball along with the playing of Fanfare for the Common Man by The New York Philharmonic.[3] Party favors are distributed to attendees, which have historically included large balloons, hats, and other items branded with the event's corporate sponsors.[7][8] At that time, hourly countdowns to the top of each hour are held until midnight, along with live music performances by popular musicians. Some of these performances are organized by, and aired on New Year's Eve television specials broadcasting from Times Square.[8][9]

The drop itself occurs at 11:59:00 p.m.,[3] and is ceremonially "activated" by a special guest (joined on-stage by the current mayor of New York City), selected yearly to recognize their community involvement or significance, by pressing a button on a smaller model of the ball.[10] The button itself does not actually start the drop; that is done from a control room, synchronized using a government time signal.[11] These guests have included various dignitaries and celebrities:

- 1996–97: Oseola McCarty[10]

- 1997–98: A group of five winners from a school essay contest honoring New York City's centennial[12]

- 1998–99: Sang Lan (who was injured during the 1998 Goodwill Games and was being rehabilitated in New York City)[13]

- 1999–2000: Dr. Mary Ann Hopkins from Doctors Without Borders[14]

- 2000–01: Muhammad Ali[15]

- 2001–02: Rudy Giuliani and Judith Nathan; this was Giuliani's final act as mayor. Michael Bloomberg officially became the new Mayor of New York City upon the beginning of 2002, and took his oath of office shortly after midnight.[16]

- 2002–03: Christopher and Dana Reeve[17]

- 2003–04: Cyndi Lauper, joined by Shoshana Johnson—the first black female prisoner of war in the military history of the United States.[18]

- 2004–05: Secretary of State Colin Powell[19]

- 2005–06: Wynton Marsalis[20]

- 2006–07: A group of eight United States Armed Forces members

- 2007–08: Karolina Wierzchowska, an Iraq War veteran and New York City Police Academy valedictorian[22]

- 2008–09: Bill and Hillary Clinton[23]

- 2009–10: Twelve students from New York City high schools on the U.S. News & World Report "America's Best High Schools Top 100 'Gold Medal' List"[24]

- 2010–11: Former Staff sergeant Salvatore Giunta[25]

- 2011–12: Lady Gaga[26]

- 2012–13: The Rockettes[27]

- 2013–14: U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor.[note 1][29][30]

- 2014–15: Jencarlos Canela, joined by a group of refugees who emigrated to New York City, in partnership with the International Rescue Committee[31][32]

- 2015–16: Hugh Evans[33]

- 2016–17: United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon; this was Ban Ki-moon's final act as UN Secretary-General, as António Guterres took office on January 1, 2017.[34][35]

- 2017–18: Tarana Burke, civil rights activist and founder of the "Me Too" movement.[36]

- 2018–19: Joel Simon, Executive Director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, and a group of eleven journalists: Karen Attiah, Rebecca Blumenstein, Alisyn Camerota, Vladimir Duthiers, Edward Felsenthal, Lester Holt, Matt Murray, Martha Raddatz, Maria Ressa, Jon Scott, Karen Toulon.[37][38]

- 2019–20: New York City high school teachers Jared Fox and Aida Rosenbaum—recipients of the 11th annual Sloan Awards for Excellence in Teaching Science and Mathematics, and four of their students.[39][40]

- 2020-21: TBA

The conclusion of the drop is followed by fireworks shot from the roof of One Times Square, along with the playing of the first verse of "Auld Lang Syne" by Guy Lombardo, "New York, New York" by Frank Sinatra, "America the Beautiful" by Ray Charles, "What a Wonderful World" by Louis Armstrong, and "Over the Rainbow " by IZ.[41]

Since the 2005–06 edition of the event, the drop has been directly preceded by the playing of John Lennon's song "Imagine". Until 2009–2010, the original recording was used; since 2010–2011, the song has been performed by the headlining artist;[42]

- 2010–11: Taio Cruz[43]

- 2011–12: CeeLo Green[note 2][44]

- 2012–13: Train[45]

- 2013–14: Melissa Etheridge[9]

- 2014–15: O.A.R.[46]

- 2015–16: Jessie J[47]

- 2016–17: Rachel Platten[48]

- 2017–18: Andy Grammer[49]

- 2018–19: Bebe Rexha[50]

- 2019–20: X Ambassadors[51]:

- 2020-21: TBA

At least 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of confetti is dropped at midnight in Times Square, directed by Treb Heining (who has been well known for his involvement in designing balloon decorations for Disney Parks, and balloon and confetti drops at other major U.S. events and celebrations, such as the presidential nominating conventions) and thrown by a team of 100 volunteers (referred to internally as "confetti dispersal engineers") lining the rooftops of eight Times Square buildings. The individual pieces of confetti are meant to be larger than normal confetti in order to achieve an appropriate density for Times Square. Some of the pieces are inscribed with messages of hope for the new year, which are submitted via a "Wishing Wall" put up in Times Square in December (where visitors can write them directly on individual pieces of confetti), and via online submissions.[52][53]

Cleanup

After the conclusion of the festivities and the dispersal of attendees, cleanup is performed overnight to remove confetti and other debris from Times Square. When it is re-opened to the public the following morning, few traces of the previous night's celebration remain: following the 2013–14 drop, the New York City Department of Sanitation estimated that it had cleared over 50 tons of refuse from Times Square in eight hours, using 190 workers from their own crews and the Times Square Alliance.[54]

History

Early celebrations, first ball (1907–1919)

The first New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square was held on December 31, 1904; The New York Times' owner, Adolph Ochs, decided to celebrate the opening of the newspaper's new headquarters, One Times Square, with a New Year's fireworks show on the roof of the building to welcome 1905. Close to 200,000 people attended the event, displacing traditional celebrations that had normally been held at Trinity Church.[55] However, following several years of fireworks shows, Ochs wanted a bigger spectacle at the building to draw more attention to the area. The newspaper's chief electrician, Walter F. Palmer, suggested using a time ball, after seeing one used on the nearby Western Union Building.[55]

Ochs hired sign designer Artkraft Strauss to construct a ball for the celebration; it was built from iron and wood, electrically lit with one hundred incandescent light bulbs, weighed 700 pounds (320 kg), and measured 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter. The ball was hoisted on the building's flagpole with rope by a team of six men. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball was designed to complete an electric circuit to light a 5-foot-tall sign indicating the new year, and trigger a fireworks show.[56] The first ever "ball drop" was held on December 31, 1907, welcoming the year 1908.[55]

In 1913, only eight years after it moved to One Times Square, the Times moved its corporate headquarters to 229 West 43rd Street. The Times still maintained ownership of the tower, however, and Strauss continued to organize future editions of the drop.[57]

The second and third balls (1920–1998)

The original ball was retired after the 1919-20 event in favor of a second design; the second ball remained 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter, but was now constructed from iron, weighing 400 pounds (180 kg).[58] The ball drop was placed on hiatus for New Year's Eve 1942-43 and 1943-44 due to wartime lighting restrictions during World War II.[58] Instead, a moment of silence was observed one minute before midnight in Times Square, followed by the sound of church bells ringing being played from sound trucks.[58]

The second ball was retired after the 1954-55 event in favor of a third design; again, it maintained the same diameter of its predecessors, but was now constructed from aluminium, and weighed 150 pounds (68 kg).[58] For the 1981-82 event, the ball was modified to make it resemble an apple (alluding to the city's nickname "the Big Apple"), by switching to red lightbulbs and adding a green "stem".[55] For the 1987-88 event, organizers acknowledged the addition of a leap second earlier that day (leap seconds are appended at midnight UTC, which is five hours before midnight in New York) by extending the drop to 61 seconds, and by including a special one-second light show during the extra second.[59] The original white bulbs returned to the ball for the 1988-89 event, but were replaced by red, white, and blue bulbs for the 1990-91 event to salute the troops of Operation Desert Shield.[55]

The third ball was revamped again in 1995 for 1996, adding a computerized lighting system with 180 halogen bulbs and 144 strobe lights, and over 12,000 rhinestones.[58][60] Lighting designer Barry Arnold stated that the changes were "something [that] had to be done to make this event more spectacular as we approach the millennium."[60]

The drop itself became computerized through the use of an electric winch synced with the National Institute of Standards and Technology's time signal; the first drop with the new system was not without issues, however, as a glitch caused the ball to pause for a short moment halfway through its descent.[61] After its 44th use in 1999, the third ball was retired and placed on display at the Atlanta headquarters of Jamestown Group, owners of One Times Square.[55]

Into the new millennium (1999–2007)

On December 28, 1998, during a press conference attended by New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, organizers announced that the third ball would be retired for the arrival of the new millennium, and replaced by a new design constructed by Waterford Crystal. The year 2000 celebrations introduced more prominent sponsorship to the drop; companies such as Discover Card, Korbel Champagne, and Panasonic were announced as official sponsors of the festivities in Times Square. The city also announced that Ron Silver would lead a committee known as "NYC 2000", which was in charge of organizing events across the city for year 2000 celebrations.[62]

A full day of festivities was held at Times Square to celebrate the arrival of the year 2000, which included concerts and hourly cultural presentations with parades of puppets designed by Michael Curry, representing countries entering the new year at that hour. Organizers expected a total attendance exceeding 2 million spectators.[63]

The fourth ball, measuring 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter and weighing 1,070 pounds (490 kg), incorporated a total of over 600 halogen bulbs, 504 triangle-shaped crystal panels provided by Waterford, 96 strobe lights, and spinning, pyramid-shaped mirrors. The ball was constructed at Waterford's factory in Ireland, and was then shipped to New York City, where the lighting system and motorized mirrors were installed.[56]

Many of the triangles were inscribed with "Hope"-themed designs changing yearly, those themes were “Star of Hope”, “Hope for Abundance”, “Hope for Healing”, “Hope for Courage”, “Hope for Unity”, “Hope for Wisdom”, “Hope for Fellowship”, and “Hope for Peace”.[3][64] For 2002, the panels featured the theme "Hope for Healing" in remembrance of the September 11 terrorist attacks: 195 of the ball's panels were engraved with the names of countries and emergency organizations that had taken casualties during the attacks, and the names of the World Trade Center, The Pentagon, and the four flights that were involved in the attacks.[65][3][64] In December 2011, the "Hope for Healing" panels were accepted into the permanent collection of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.[65]

Present day (2008–present)

In honor of the ball drop's centennial anniversary, a brand new fifth design debuted for New Year's Eve 2008. Once again manufactured by Waterford Crystal with a diameter of 6 feet (1.8 m), but weighing 1,212 pounds (550 kg), it used LED lamps provided by Philips (which can produce 16,777,216 or 224 colors), with computerized lighting patterns developed by the New York City-based lighting firm Focus Lighting. The ball featured 9,576 energy-efficient bulbs that consumed the same amount of electricity as only 10 toasters.[2] The 2008 ball was only used once, and was placed on display at the Times Square Visitors Center following the event.[55][61][66]

For 2009, a larger version of the fifth ball was introduced—an icosahedral geodesic sphere lit by 32,256 LED lamps. Its diameter is twice as wide as the 2008 ball, at 12 feet (3.7 m), and contains 2,688 Waterford Crystal panels, with a weight of 11,875 pounds (5,386 kg). It was designed to be weatherproof, as the ball would now be displayed atop One Times Square nearly year-round following the celebrations.[55][61][66]

Yearly themes for the ball's crystal panels continued; from 2008 to 2013, the ball contained crystal patterns that were part of a Waterford series known as "World of Celebration", which included "Let There Be Light", “Let There Be Joy”, “Let There Be Courage”, “Let There Be Love”, “Let There Be Friendship”, and "Let There Be Peace". For 2014, all the ball's panels were replaced, marking a new theme series known as "Greatest Gifts", beginning with "Gift of Imagination".[32][47][66][67]

The numerical sign indicating the year (which remains atop the tower along with the ball itself) uses Philips LED lamps. The "14" digits for 2014 used Philips Hue multi-color LED lamps, allowing them to have computerized lighting cues.[68]

Weather at midnight

According to National Weather Service records, since 1907–08, the average temperature in nearby Central Park during the ball drop has been 34 °F (1 °C). The warmest ball drops occurred in 1965–66 and 1972–73 when the temperature was 58 °F (14 °C). The coldest ball drop occurred in 1917–18, when the temperature was 1 °F (−17 °C) and the wind chill was −18 °F (−28 °C). Affected by a continent-wide cold wave, the 2017–18 drop was the second-coldest on record, at 9 °F (−13 °C) and −4 °F (−20 °C) after wind chill. The third coldest ball drop occurred during the 1962-63 event, when the temperature was 11 °F (-11 °C) and the wind chill was -17 °F (-27 °C)[69][70] Snow has fallen seven times, with the earliest being the 1926-27 event, and the most recent being the 2009–10 event, and rain or drizzle has fallen sixteen times, with the earliest being the 1918-19 event, and the most recent being the 2018–19 event. The snowiest ball drop occurred during the 1948-49 event, when 4 inches of snow fell, and the rainiest occurred during the 2018-19 event, when 1.02 inches of rain fell.[71]

Broadcasting

As a public event, the festivities and ball drop are often broadcast on television. A host pool feed is provided to broadcasters for use in coverage, which for 2016–2017 consisted of 21 cameras.[72] Since 2008–2009, an official webcast of the ball drop and its associated festivities has been produced, streamed via Livestream.com.[72][73][74]

The event is covered as part of New Year's Eve television specials on several major U.S. television networks, which usually intersperse on-location coverage from Times Square with entertainment segments, such as musical performances (some of which held live in Times Square as part of the event program). By far the most notable of these is Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve; created, produced, and originally hosted by the entertainer Dick Clark until his death in 2012 (with Regis Philbin filling in for him for its 2004-05 broadcast), and currently hosted by Ryan Seacrest, the program first aired on NBC in 1972 before moving to ABC, where it has been broadcast ever since.[75][76] New Year's Rockin' Eve has consistently been the most-watched New Year's Eve special in the U.S. annually, peaking at 25.6 million viewers for its 2017–18 edition.[77][75][78] Following the death of Dick Clark in April 2012, a crystal engraved with his name was added to the 2013 ball in tribute.[76]

Across the remaining networks, NBC broadcasts NBC's New Year's Eve (formerly New Year's Eve with Carson Daly), which features The Voice host Carson Daly, while Fox has presently aired a New Year's special hosted by comedian and media personality Steve Harvey since 2017–18. Spanish-language network Univision broadcasts ¡Feliz!, hosted by Raúl de Molina of El Gordo y La Flaca.[79][80][81]

On cable, CNN carries coverage of the festivities, known as New Year's Eve Live, currently hosted by Anderson Cooper and Andy Cohen (the latter first replacing Kathy Griffin for 2018).[82] Fox News carries All-American New Year, which was most recently hosted by Elisabeth Hasselbeck and Bill Hemmer from Times Square.[83]

Past broadcasts

Beginning in the 1940s, NBC broadcast coverage from Times Square anchored by Ben Grauer on both radio and television. Its coverage was later incorporated into special episodes of The Tonight Show, continuing through Johnny Carson and Jay Leno's tenures on the program. NBC would later introduce a dedicated special, New Year's Eve with Carson Daly, hosted by former MTV personality Carson Daly.[84]

From 1956 to 1976, CBS was well known for its television coverage of the festivities hosted by bandleader Guy Lombardo, most frequently from the ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, featuring his band's signature rendition of "Auld Lang Syne" at midnight (which in contemporary times has traditionally been played at midnight in Times Square).[41] After Lombardo's death in 1977, CBS and the Royal Canadians, now led by Victor Lombardo, attempted to continue the special. However, Guy's absence and the growing popularity of ABC's New Year’s Rockin’ Eve prompted CBS to eventually drop the band entirely. In 1979 the Royal Canadians were replaced by a new special, Happy New Year, America, which ran in various formats with different hosts (such as Paul Anka, Donny Osmond, Andy Williams, Paul Shaffer, and Montel Williams) until it was discontinued after 1996. CBS, except for coverage during a special episode of Late Show with David Letterman for 1999, and a special America's Millennium broadcast for 2000, has not broadcast any national New Year's programming since.[85][86][87][88]

For 2000, in lieu of New Year's Rockin' Eve, ABC News covered the festivities as part of its day-long telecast, ABC 2000 Today. Hosted by then-chief correspondent Peter Jennings, the broadcast featured coverage of New Year's festivities from around the world as part of an international consortium. Jennings was joined by Dick Clark as a special correspondent for coverage from Times Square.[89]

MTV had broadcast coverage originating from the network's Times Square studios at One Astor Plaza. For 2011, MTV also held its own ball drop in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, the setting of its popular reality series Jersey Shore, featuring cast member Snooki lowered inside a giant "hamster ball". Originally, MTV planned to hold the drop within its studio in Times Square, but the network was asked by city officials to conduct the drop elsewhere.[90]

For 2019, prominent video game streamer Ninja hosted a 12-hour New Year's Eve broadcast on Twitch from Times Square, streaming matches of Fortnite Battle Royale with himself and special guests from a studio in the Paramount Building. Ninja made an on-stage appearance in Times Square during the festivities outside, where he attempted to lead the crowd in a floss dance (a routine made popular by Fortnite).[91][92] The event became a meme due to his failure to do so.

Notes

- Michael Bloomberg, whose mayoral term ended at midnight, did not attend, and celebrated privately with his family instead. Unlike Bloomberg's inauguration in 2002, which was held shortly after midnight, Bill de Blasio was inaugurated in a ceremony the following morning at Gracie Mansion.[28]

- Cee-Lo's performance was criticized by fans for his change of the lyric "And no religion too" to "And all religion's true".[44]

References

- "Nearly 800 Hard At Work On Times Square New Year's Eve Celebration". CBS New York. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "NYC ball drop goes 'green' on 100th anniversary". CNN. December 31, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- "Countdown to Times Square party; 1 million expected". CNN. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "New Year's Eve security main focus for NYPD". CNN. December 30, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Mueller, Benjamin (December 28, 2017). "In Wake of Attacks, Tighter Security for Times Square on New Year's Eve". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- Holley, Peter (December 31, 2018). "The NYPD planned to use drones during Times Square New Year's Eve celebration. Then it started raining". Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "For New Year's Eve, the Tie-Ins Erupt". The New York Times. December 13, 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "A Very Confetti New Year's". Time. January 2, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- Mansfield, Brian (December 26, 2013). "Etheridge added to Times Square New Year's Eve lineup". USA Today. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "Mayor Giuliani Announces New Traditioin for New Year's Eve: Community Hero to Lead Times Square Celebration". City of New York. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Balkin, Adam (December 30, 2003). "Technology Helps Times Square New Year's Eve Ball Drop Run Smoothly". NY1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "City Keeps the Ball Rolling – It's Another Round in Times Sq. for Seasoned Partyers". New York Daily News.

- "On the ball: Sang Lan was in the spotlight on New Year's..." Chicago Tribune. January 5, 1999. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Doctors Without Borders to Join Times Square Ball Drop During New Year's Eve Festivities". City of New York. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- "Ali To Drop Ball On New Year's". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- "Inaugural Address Of Mayor Michael Bloomberg". Gotham Gazette. January 1, 2002. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- "Huge Times Square Crowd Watches Ball Drop". Fox News. Associated Press. January 1, 2003. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- "Bloomberg Announces Special Guest For New Year's 2004 Celebration In New York". Life. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Regis, Colin Powell ring in New Year's with'energy, enthusiasm'". USA Today. January 1, 2005. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Neither rain nor snow slows Times Sq. party". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Times Square New Year's gala turns 100". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Revelers ring in 2009 in Times Square". Associated Press. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- "America's Best High Schools Heads to Times Square". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Sgt. Salvatore Giunta in NYC for New Year's Eve". Associated Press. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- "Lady Gaga to perform on New Year's Eve in Times Square". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- Seifman, David (December 28, 2012). "Rockettes to join Mayor Bloomberg on New Year's Eve". New York Post. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- "Nearly 800 Hard At Work On Times Square New Year's Eve Celebration". CBS New York. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Costa, Robert (December 30, 2013). "Sotomayor to officiate at Times Square New Year's Eve". Washington Post. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Brrr-Braving the Ball Drop". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "New Year's In Times Square: Jencarlos Canela Will Be The First Latino To Push Ball Drop Countdown Button". Latin Times. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "Crystal Ball Nearly Ready For New Year's Eve In Times Square". CBSNewYork.com. CBS Corporation. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- "Activist to Help Drop Crystal Ball In Times Square". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- "António Guterres appointed next UN Secretary-General by acclamation". United Nations. United Nations News Service. October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- "U.N. secretary-general to kick off Times Square New Year's Eve countdown". NBC News. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Founder of "Me Too" Movement, Tarana Burke, to be Special Guest of Times Square New Year's Eve" (PDF). timessquarenyc.org. Times Square Alliance. December 18, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- Wise, Justin (December 19, 2018). "Times Square New Year's celebration to honor media by bringing journalists onstage for ball drop". TheHill. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "Times Square New Year's Eve Announces Journalists who will be Honored as the Evening's Special Guests" (PDF). timessquarenyc.org. Times Square Alliance. December 29, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- Parnell, Wes; McShane, Larry. "A Times Square deal: Four NYC high schoolers, two teachers get honor of pressing the button for the New Year's Eve ball drop ringing in 2020". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "North Greenbush native to be part of Times Square celebration". Times Union. December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Across America, traditions of ham hocks, Watch Nights and the Times Square ball". NBCNews.com. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Cooper, Gael Fashingbauer (January 1, 2012). "Fans angry that Cee Lo changed 'Imagine' lyrics". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- "Cruz To Perform 'Imagine' During New Year's Celebration". CBSNewYork.com. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/cee-lo-green-outrages-john-lennon-fans-by-changing-lyrics-to-imagine-202240/

- "Live Times Square New Year's Eve Webcast: Watch Train, Cassadee Pope". Billboard.com. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "New Year's Eve Organizers Release Star-Studded Roster Of Musical Talent Set To Perform Live In Times Square". TimesSquareNYC.org. Times Square Alliance. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- "Workers To Install 288 New Waterford Crystals On New Year's Eve Ball". CBS New York. CBS Radio. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "Times Square Alliance : Gavin DeGraw and Rachel Platten to Headline Musical Lineup for Times Square New Year's Eve Live, Commercial-Free Webcast and TV Pool Feed". TimesSquareNYC.org. Times Square Alliance. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- "Multi-Platinum Pop Singer and Songwriter Andy Grammer to Headline Musical Lineup for Times Square New Year's Eve Live, Commercial-Free Webcast and TV Pool Feed" (PDF). timessquarenyc.org. Times Square Alliance. December 18, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "Multi – Platinum Pop Singer, Songwriter and 2019 Grammy Award Nominee Bebe Rexha to Headline Musical Lineup for Times Square New Year's Eve, with Chart – Topping Alt – Pop Band lovelytheband, on the Live, Commercial – Free Webcast and TV Pool Feed" (PDF). timessquarenyc.org. Times Square Alliance. December 13, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- Hudak, Joseph (December 30, 2019). "New Year's Eve 2020: How to Watch, Who's Performing, Ball Drop". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Times Square NYE ball drop: It takes a 'confetti master' and his team to pull it off". AM New York. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Mestel, Spenser (December 28, 2018). "How to Dump 3,000 Pounds of Confetti on Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Crews Clean Up Times Square After New Year's Celebration". CBSNewYork.com. CBS Radio. January 1, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- Feuer, Alan (December 27, 2009). "Deconstructed – Times Square Ball – Lots of Sparkle for a Swift Fall". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Kushner, David (December 30, 1999). "This New Year's Eve, Technology Will Drop the Ball". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "History of Times Square". London: The Telegraph. July 27, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Crump, William D. (2014). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland. p. 242. ISBN 9781476607481.

- McFadden, Robert D. (December 31, 1987). "'88 Countdown: 3, 2, 1, Leap Second, 0". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- Sutton, Larry. "Bigger Ball to Peg Square". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- Barron, James (December 31, 2009). "When Party Is Over, the Ball Lands Here". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Goodnough, Abby (December 29, 1998). "Here Comes 2000, With Sponsors, Too; Official Products in the Right Place: Millennial Partying in Times Sq". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Kelley, Tina (December 30, 1999). "There's Another Countdown Before the Famed '10, 9, 8 . . .'". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "New Year Theme Right On The Ball". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Memorial Museum to Accept Crystals from 2001–2002 Times Square Ball Honoring 9/11 Victims, Heroes". National September 11 Memorial & Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "New Year's Eve Preparations Under Way In Times Square". CBSNewYork.com. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "Waterford and Times Square New Year's Eve Reveal "Gift of Imagination" Crystal Design as Part of New 10-Year "Greatest Gifts" Series". Waterford Crystal press release. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "Philips hue to Mark Colorful Start to 2014 at Times Square New Year's Eve Celebration" (Press release). Philips. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- "Times Square braces for one of coldest New Year's Eve parties on record". The Guardian. Associated Press. December 31, 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- Theresa Waldrop; Catherine E. Shoichet. "New year brings record cold across US". CNN.com. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- "New Year's Eve/Ball Drop Weather at Central Park" (PDF). National Weather Service Forecast Office New York, New York. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- "Meet the Team Behind Times Square New Year's Eve". TV Technology. NewBay Media. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Taub, Erica A. (December 24, 2009). "New Year's Eve in Times Square Is Now a Webcast". The New York Times. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Shriver, Jerry (December 27, 2007). "Extra-bright ball to drop at Times Square". USA Today. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Stelter, Brian (December 31, 2011). "4 Decades Later, He Still Counts". New York Times. p. C1. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- Barmash, Jerry. "Marking New Year's Eve at Times Square Without Dick Clark". FishbowlNY. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- Mitovich, Matt Webb (January 1, 2018). "Ratings: Ryan Seacrest's Rockin' Eve Hits All-Time Highs, Fox's Steve Harvey a Big Improvement Over Pitbull". TVLine. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Levin, Gary (January 4, 2012). "Nielsens: Clark's 'Rockin' Eve,' football start year well". USA Today. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- "Ring in the new year with Ryan, Carson or Anderson". Bradenton Herald. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- "Pitbull to Host New Year's Eve Live Show for Fox". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- "Fox Swaps Pitbull for Steve Harvey on New Year's Eve". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- Steinberg, Brian (October 11, 2017). "CNN Will Replace Kathy Griffin With Andy Cohen for New Year's Eve". Variety. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- "TV highlights: Networks compete for most entertaining New Year's show". Washington Post. December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- Oldenberg, Ann (December 29, 2005). "Battle of Times Square". USA Today. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- Lynch, Stephen (December 31, 1999). "New Year's song remains ingrained in public mind". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on April 26, 2005.

- Collins, Scott (December 25, 2006). "Past, Present, and...Future?". Los Angeles Times. p. E1.

- Moore, Frazier (December 26, 2001). "Next week to be 25th New Year's Eve without Guy Lombardo". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- Terry, Carol Burton. "New Guy Lombardo? Dick Clark sees New Year's tradition". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Bobbin, Jay (December 28, 2000). "Dick Clark offers longer New Year's Eve special". Ellensburg Daily Record. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- "Snooki 'dropped' from Times Square New Year's Eve celebration". Staten Island Advance. December 30, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- Statt, Nick (October 26, 2018). "Fortnite star Ninja is getting his own 12-hour New Years Eve broadcast in Times Square". The Verge. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- "'Fortnite' Star Ninja's Attempt To Get Times Square To Do The Floss Dance Fails Miserably". Comicbook.com. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Times Square Ball. |