Timeline of Cluj-Napoca

The following detailed sequence of events covers the timeline of Cluj-Napoca, a city in Transylvania, Romania.

Cluj-Napoca (Romanian pronunciation: [ˈkluʒ naˈpoka] (![]()

![]()

In modern times, the city holds the status of municipiu, is the seat of Cluj County in the north-western part of Romania, and continues to be considered the unofficial capital of the historical province of Transylvania. Cluj continues to be one of the most important academic, cultural, industrial and business centres in Romania. Among other institutions, it hosts the country's largest university, Babeș-Bolyai University, with its famous botanical garden. The current boundaries of the municipality contain an area of 179.52 square kilometres (69.31 sq mi). The Cluj-Napoca metropolitan area has a population of 411,379 people, while the population of the peri-urban area (Romanian: zona periurbană) exceeds 420,000 residents, making it one of the most populous cities in Romania.

2nd century

.svg.png)

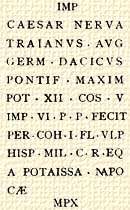

- 101 - After gaining support from the Roman Senate, emperor Trajan leads the Roman legions across the Danube into Dacia, starting the First Dacian War.[1]

- 102 - Hostilities between Roman Empire and Dacian Kingdom cease and the two parties reach a peace agreement.[2]

- 105 - Trajan starts the second Dacian campaign with aim of expansion and conquest.[1]

- 105-106 - During the second campaign, the Romans build Castra of Napoca.[3]

- 106 - 11 August

- the territories annexed from the Kingdom of Dacia officially become the imperial province of Dacia.[4]

- Decimus Terentius Scaurianus, who commanded legions during the Dacian wars, is named the propraetorian governor.[5]

- 107

- 108

- Napoca is mentioned as a vicus, an ad hoc provincial civilian settlement, which sprang up close to the military castra.[10]

- The work to the Roman road connecting Napoca to Potaissa finishes[8], increasing significantly the importance of Napoca

- The town becomes the end of the central spine from which all of the Roman forts in Northwest Dacia can be reached.[11]

- c.108-124

- 117

- 118 - After the battles with Roxolani and the Iazyges where Hadrian himself participates, the provinces of Moesia and Dacia are reorganized, Trajan's original province of Dacia being relabelled Dacia Superior.[14]

- 124

- Emperor Hadrian visits Napoca in Dacia[3], grants the title and rank of municipium[15] (as municipium Aelium Hadrianum Napocenses[16]) and attaches it to his tribe, the Sergia.[17]

- Province of Dacia is reorganized, and an additional province called Dacia Porolissensis is created in the northern portion of Dacia Superior[18][14]

- Napoca becomes the location of the military high command in Dacia Porolissensis[19] and its capital.[20]

- Livius Gratus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.

- 131 - Flavius Italicus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[21]

- 138 - 11 July: Antoninus Pius becomes emperor at Hadrian's death.

- 151 - Marcus Macrinius Vindex becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[21]

- 157 - Tiberius Clodius Quintianus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[21]

- 161 - 8 March: Marcus Aurelius succeeds Antoninus Pius as Emperor.

- 161-162 - Volu[---] becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[21]

- 164 - Lucius Sempronius Ingenuus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[21]

- 166

- Pressures building along the Danube frontier force Marcus Aurelius to set up an overarching province, Tres Daciae (Three Dacias), which fuses the three Dacia provinces into one and is commanded by a consular legate.

- The three provinces, including Dacia Porolissesnsis, still remain as separate entities, each one governed by a praesidial procurator, who then reports to the proconsular governor.

- Sextus Calpurnius Agricola becomes the first Legatus Augusti pro praetore (consular legate) of the Tres Daciae.

- 168 - Marcus Claudius Fronto becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- 170 - Sextus Cornelius Clemens becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- 173 - Lucius Aemilius Carus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- 176 - Gaius Arrius Antoninus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- 177

- Marcus Aurelius bestows the title of Augustus on his son, Commodus, giving him the same status as his own and formally starting to share power.

- Publius Helvius Pertinax becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- c.178–179 - Marcus Valerius Maximianus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- 180

- 17 March: Marcus Aurelius dies and Commodus remains sole emperor

- Gaius Vettius Sabinianus Julius Hospes becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- c.180 - the city gaines the status of a colonia as Colonia Aurelia Napoca.[17][24]

- c.180–190 - Gaius Valerius Catulinus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- c.180-192

- Eocene limestone is extracted from the stone quarries around Hoia Hill to the west of the town[25] on a large scale.[26]

- The city wall around the precinct is constructed using large blocks of limestone in opus quadratum, covering a surface of around 25 hectares.[13]

- A brooch workshop is built using stone.[13]

- 182 - Lucius Vespronius Candidus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[21]

- 185

- Dacian revolt in the province, Free Dacians living outside the borders also defeated.[27]

- Commodus' legates devastate a territory some 8 km (5 mi) deep along the north of the Castrum Gilău (near Napoca) to establish a buffer in the hope of preventing further barbarian incursions.[28]

- c.185 - Gaius Pescennius Niger becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- c.190 - G. C(...) Hasta becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 191 - Aelius Constans becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- 192 - 31 December: Emperor Commodus is assassinated.

- 193 - 14 April: Septimius Severus' legion, XIV Gemina, proclaims him Emperor.

- c.193-211: The villa rustica from Apahida (near Napoca) is in use.[29]

- c.193 - Quintus Aurelius Polus Terentianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 195 - Publius Septimius Geta becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- c.197 - Pollienus Auspex becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 198 - Caracalla is appointed by his father, Septimius Severus, as joint Augustus and full Emperor.

- c.198–209 - Publius Aelius Sempronius Lycinus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- c.198–209 - Gaius Publicius Antonius Probus becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- 200 - Lucius Octavius Julianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- c.200 - Marcus Cocceius Genialis becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

3rd century

- c.200-230 - Marcus Veracilius Verus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- 204 - Lucius Pomponius Liberalis becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 205 - Mevius Surus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 206 - Claudius Gallus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 208 - Gaius Julius Maximinus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 211 - 4 February: Caracalla and his brother Geta reign together after their father's death.

- c.211-217 - The road from Napoca to Porolissum is repaired.[31]

- 212 - Lucius Marius Perpetuus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[23]

- 215 - Gaius Julius Septimius Castinus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- 217 - Marcus Claudius Agrippa becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- c.217 - Ulpius Victor becomes procurator of Dacia Porolissensis.[22]

- 222 - 11 March: Severus Alexander becomes Emperor.

- c.222 - Iasdius Domitianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- 235 - 20 March 235: Maximinus Thrax succeeds to the rule of Roman Empire, after Severus Alexander is assassinated.

- c.235-238 - Quintus Julius Licinianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- c.235-238 - Marcus Cuspidius Flaminius Severus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- c.235-238 - Decimus Simonius Proculus Julianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- 236-238 - Maximinus Thrax campaigns in Dacia against the Carpi.[32]

- c.238 - Decimus Simonius Proculus Julianus becomes the consular legate of the Three Dacias.[30]

- 242-247 - Carpi are attacking Dacia and Moesia Inferior.[33]

- 248-250 - Dacia is attacked by the Germanic tribes of the Goths, Taifals and Bastarns together with the Carpi.[34]

- 253

- 257 - Gallienus claims the title Dacicus Maximus after repeated victories over the Carpi and associated Dacian tribes.[36]

- 258 - Dacia is attacked by Carpi and Goths.[34]

- 258-260 - A percentage of the cohorts from the V Macedonica and XIII Gemina legions are transferred from Dacia to Pannonia.[37]

- 260 - Monetary circulation[35] and raising of inscribed monuments[38] have a dramatic drop in Dacia.

- c.260 - Repairs of the castra fortifications are conducted on the northern border of Dacia Porolissensis.[35]

- 263 - Dacia is attacked by Carpi and Goths.[34]

- 267 - Dacia is attacked by Goths and Herules.[34]

- 269 - Dacia is attacked by Goths and Herules.[34]

- 270 - September: Aurelian becomes Roman Emperor.

- 271-275 - Aurelian evacuates the Roman troops and civilian administration from Dacia, and establishes Dacia Aureliana with its capital at Serdica in Lower Moesia.[33][39]

- c.291

- Goths, including Thervingi, begin to move into the former province of Dacia.[40]

- Victohali, a subdivision of Hasdingi (themselves southern Vandals), push from north and west into north west of Dacia.[41]

- Taifals join Thervingi to fight Victohali and Gepids over the possession of Samus valley.[42]

- Gepids mentioned for the first time.[41]

- 291-300 - Thervingi continue migrating into north-eastern Dacia but are opposed by the Carpi and the non-Romanized Dacians.[43]

- c.295 - Goths defeat the Carpi, pushing them southward.[44]

4th century

- 295-320s - After a peace treaty with the Romans, Goths proceed to settle down in parts of Roman Dacia (starting to be called Gothia), dividing some of the land with the Taifals[45], and co-existing with the remaining semi-Romanized population.[43]

- c.300-350 - Ruralization of the urban life in Dacia.[46]

5th century

- c.401-420 - Gepidic center on the plains north-west of the Meseş Mountains.[50][51]

- 420s - Huns impose their authority over the Gepids[51], but the latter remain united under the rule of their kings.[52]

- c.440 - Ardaric, favored by the Hunic king, becomes the leader of the Gepids.[52]

- c.435–453 - Huns fight the Alans, Vandals, and Quadi, forcing them toward the Roman Empire and making Pannonia their center.[53]

- 453 - Attila, King of the Huns dies and the Hunnic Empire starts to disintegrate.

- c.454

- Ardaric initiates an uprising of the Gepids against the Huns.[54]

- Gepids defeat the Huns in Pannonia, regain their independence[55] and are able to start to expand eastwards, into Dacia.[56][53]

- c.475-500

- Gepid power centers start to develop in Transylvania.[33]

- Major, wealthy Gepid center at Apahida, near Napoca[52], having connections with the Eastern Roman Empire.[57][52]

6th century

- c.501-568

- More Gepid power centers appear in Transylvania.[33]

- New settlements appear along the Someş, Mureş, and Târnava rivers, reflecting a period of tranquillity in Gepidia.[58]

- A "circle" of Gepid settlements develops around Napoca.[59]

- Gepids start to adopt Arian Christianity through their connection with the Goths.[60]

- Farming is the primary activity, but looms, combs, and other items are produced in local workshops.[58]

- Gepidia is trading with faraway regions such as Crimea, Mazovia or Scandinavia.[61]

- 568 - The Avar invasion ends the independent Gepidia.[62]

- c.568 - Carpathian Basin is incorporated in the Avar Khaganate established by khagan Bayan I.

- c.599-600 - Gepids under assimilation but settlements still exist within Avaria.[63][64]

7th century

- c.600-800 - Avars bring with them and allow Slavs to settle inside Transylvania.

8th century

- c. 700-800 - Center and northern Transylvania under Moravian influence.[33]

- 791–795 - Plunder of the Avar state by the Franks of Charlemagne.[65]

- 794 - Avars, in small numbers, and mixed with Slavs, still inhabit parts of Transylvania.[65]

- 796 - Avar Khaganate suffers a crippling blow by the Franks.[65]

9th century

- c.796-803 - Bulgars under Khan Krum unite with Franks to crush the Avar Khaganate.[65]

- c.803

- Transylvanian Avars are subjugated by the Bulgars under Khan Krum

- Transylvania and eastern Pannonia are incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire.

- Salt mines of Transylvania under Bulgar control.

- c.850-900

10th century

- c. 895–902 - Magyars (Hungarians) commence the conquest of the Carpathian Basin defeating and conquering the lands of Menumorut and later Gelou

- c. 902-950 - Area falls under the rule of Tuhutum (Tétény) and his descendants [72][73] (within newly formed Principality of Hungary)

- c. 900-1000

- A small settlement appears on the ruins of Roman Napoca covering less than 3rd of the ancient site, with Roman fortifications being used as a source of construction materials.[74]

- The settlement has four unequal sides (northern side 250 m, western side 223 m, southern side 300m, eastern side 197 m).[74]

- A cemetery is active 600-1300 m from Napoca.[75]

- 1000 - Area becomes part of the Kingdom of Hungary, as Stephen I of Hungary is crowned as the first king and adopts Christianity.[76][77]

11th century

- c. 1001-1038

- Stephen I establishes an administrative system of counties based on fortresses (or comitati) using the French model, with four of them in Transylvania, including the Kolozs County.[78]

- Each county (or comitatus (Latin)) is led by a count (comes (Latin) or Ispán (Hungarian)).[78]

- The new Ispán of Kolozs (comes Clusiensis) is responsible with the protection of the salt production in nearby Koloszokna.[74]

- A fort is erected at Kolozsmonostor (3 km from the ancient Napoca) to serve as the count's residence.[79]

- 1009 - Diocese of Transylvania is established.[80]

- 1068 - Kolozsmonostor fort and settlement are destroyed by fire during an incursion of the Pechenegs in Transylvania.[81]

- 1080s-1090s

- Kolozsmonostor fort reconstructed, having its earth-and-beam wall raised by three metres.[81]

- Ladislaus I of Hungary settles Benedictine monks on the fort premises, who establish Kolozsmonostor Abbey, the first Benedictine monastery in Transylvania.[82][83][84]

- First church is constructed in Kolozs.[85]

12th century

- 1111-1113 - Mercurius, a distinguished nobleman who held the office during the reign of Coloman, King of Hungary (1095–1116)[86] , is mentioned in two royal charters as "princeps Ultrasilvanus" (perhaps the first known Voivode of Transylvania)[87]

- 1143 - The colonization of Transylvania by Germans commences under the reign of King Géza II of Hungary (1141–1162)

- 1173 - Clus as a county name is recorded for the first time, in a document which mentions Thomas comes Clusiensis[88]

- 1176 - Leustach of the Rátót clan becomes Voivode of Transylvania.

- 1178 - Site "colonized" by newly arrived "Saxons".[89]

- 1199 - Legforus becomes Voivode of Transylvania.

13th century

- 1213 - The first written mention of the city's current name – as a Royal Borough – under the Medieval Latin name Castrum Clus.[90]

- 1241 - Both Kolozs and Kolozsmonostor are destroyed during First Mongol invasion of Hungary, with very few survivors.[91]

- 1246 - The first recording for the Hungarian form Kolozsvár (uar / vár means "castle" in Hungarian).[92]

- c. 1242-1275 - More German colonists arrive from Rhineland and Flanders, and are working to rebuild the fortress of Kolozs.[91]

- 1275 - In a document of King Ladislaus IV of Hungary, the village (Villa Kulusvar) is granted to Peter Monoszló, the Bishop of Transylvania.[93]

- c. 1260-1290 - A new church in built in Kolozs in Late Romanesque style, on the site of the destroyed first church, and then starts to serve as the parochial church.[85]

- 1285-1286 - Second Mongol invasion of Hungary

14th century

- 1316

- August 19: King Charles I of Hungary grants the status of a city (Latin: civitas), as a reward for the Saxons' contribution to the defeat of the rebellious Transylvanian voivode, Ladislaus Kán.[93]

- Groundbreaking for the St. Michael's Church[94]

- 1332 - The first appearance of the Hungarian form Koloswar, as it underwent various phonetic changes over the years.[92]

- 1348 - First usage of the Transylvanian Saxon name of Clusenburg/Clusenbvrg appeared.[92]

- 1349 - A document signed by the archbishop of Avignon and fifteen other bishops grants the indulgence for those contributing to the illumination and furniture of the St. Michael's Church.

- 1377 - King Louis I of Hungary grants to Cluj the coat of arms and seal, consisting of three towers, a city wall with a gate in silver on a blue background.

- 1390

- The altar of St. Michael's Church is inaugurated[94] and the church starts to be used as the new parochial church of Kolozs.[85]

- The original church from the Old Town is given to friars of the Dominican Order.[85]

15th century

- 1405 - Through the privileges granted by Sigismund of Luxembourg, Cluj becomes a royal free city, is opting out from the jurisdiction of voivodes, vice-voivodes and royal judges, and obtains the right to elect a twelve-member jury every year.[95]

- 1408 - First mention of the Transylvanian Saxon form Clausenburg.[92]

- 1432 - St. Michael's Church is completed.[89]

- 1442 - Dominican friars begin the construction of their monastery and to rebuild the old church in Gothic style.[85]

- 1443 - 23 February: Matthias Corvinus is born in Cluj.

- 1445 - John Hunyadi starts supporting the construction efforts of the Dominican friars, offering a guaranteed income of 50 cubes of salt from the salt mine of Szék.[85]

- 1464 - 29 April: Matthias Corvinus becomes King of Hungary.

- 1481 - First record of the presence of Jews living in Cluj.[96]

16th century

- 1511-1545 - Tower of St. Michael's Church is built.

- 1541 - City stays in Eastern Hungarian Kingdom after the Ottoman Turks occupied the central part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

- 1543 - Bonțida Bánffy Castle built near city.

- 1544 - Kaspar Helth (Hungarian: Gáspár Heltai), a Transylvanian Saxon who studied at Wittenberg University, comes to Kolozsvár as a Lutheran preacher, marking the arrival of Reformation in the city.[97]

- 1550 - Printing press is established in the city by Kaspar Helth.[98][99]

- 1565 - Witch trials begin.[100]

- 1568 - Unitarian Church of Transylvania is founded by Dávid Ferenc, who was previously a Catholic priest, later a Lutheran one and then a Calvinist bishop

- 1570 - City becomes part of the independent Principality of Transylvania, established through the Treaty of Speyer

- 1572 - Filstich Wolf House built in Big Market Square.

- 1581 - Gymnasium (school) founded.[101]

- 1593 - Witch trials end, with thirteen people being burned.[100]

17th century

- 1615 - Witch-hunt starts.[100]

- 1629 - Witch-hunt ends.[100]

- 1695 - Hungarian Szakácskönyv (cookbook) published.[102][103]

- 1699 - City becomes part of the Habsburg Monarchy per Treaty of Karlowitz.

18th century

- 1715 - Construction of the Citadel begins.[89]

- 1785

- Bánffy Palace built.

- Gherla Prison begins operating in vicinity.

- 1790 - City becomes capital of the Grand Principality of Transylvania.

- 1792 - Hungarian Theatre founded.

- 1798 - Large parts of the city destroyed by fire.[89]

19th century

- 1803 - Bob Church consecrated.

- 1812 - Reduta Palace built.

- 1828 - Josika Palace expanded.

- 1829 - Evangelical-Lutheran Church built.

- 1830s - Népkertnek Park (Central Park) opens.

- 1845 - Town Hall built.[104]

- 1848 - 25 December: City taken by Hungarian forces.[105]

- 1869 - Institute of Agronomic Studies founded.

- 1870

- 1872 - Franz Joseph University[107] and Botanical Garden founded.

- 1880 - Population: 29,923 (70% of Hungarian ethnicity).[108]

- 1887 - Neolog Synagogue built.

- 1890 - Population: 32,739.[109]

- 1895 - New York Café built.

- 1900 - Population: 46,670.[89]

20th century

.png)

- 1902

- Palace of Justice built.

- Matthias Corvinus Monument unveiled in Big Market Square.[110]

- 1906 - Cluj-Napoca National Theatre opens.

- 1907 - CFR Cluj (football club) formed.

- 1910 - Hungarian Theatre of Cluj building constructed.

- 1911 - Ion Moina Stadium opens.

- 1913 - Sebestyén Palace built in Big Market Square.

- 1918

- 1 December: Union of Transylvania with Romania is declared

- 24 December: City taken by Romanian forces; Hungarian rule ends.[111]

- 1919

- Iulian Pop becomes the first Romanian mayor.

- U Cluj football club formed.

- Gheorghe Dima Music Academy founded.

- 1920

- Based on the Treaty of Trianon, Cluj becomes part of the Kingdom of Romania.[112]

- Population: 85,509.

- 1921 - 28 September: Capitoline Wolf Statue, a gift from Italy to Romania as a symbol for its Latinity, unveiled in Unirii Square.[113]

- 1922 - Ethnographic Museum of Transylvania founded.

- 1925 - Fine Arts School founded.

- 1930

- 1933 - Dormition of the Theotokos Cathedral (Romanian Orthodox) built.[115]

- 1934 - Goldmark Jewish Symphonic Orchestra founded.[116]

- 1940 - City becomes part of Hungary again.[112]

- 1944

- 1948

- Protestant Theological Institute established.

- Population: 117,915.[112]

- 1966 - Population: 185,663 (56% of Romanian ethnicity; 42% of Hungarian ethnicity).[108]

- 1968 - Echinox literary magazine begins publication.

- 1973 - CFR Cluj Stadium opens.

- 1974

- City renamed to "Cluj-Napoca".

- Population: 218,703.[118]

- 1989 - December: Romanian Revolution.

- 1992

- Gheorghe Funar becomes mayor.

- Population: 328,602 (75% of Romanian ethnicity).[108]

- 1994 - Association for Interethnic Dialogue established in Cluj.[119]

21st century

- 2001 - Peace Action, Training and Research Institute of Romania (PATRIR) founded.[120]

- 2004 - Emil Boc becomes mayor.

- 2008

- Sorin Apostu becomes mayor.

- Cluj-Napoca metropolitan area created.

- 20 November: Demolition of Ion Moina Stadium starts.

- 2009 - July 16: Construction of the new stadium, Cluj Arena, begins on the site of demolished Ion Moina Stadium.

- 2011

- Population: 324,576 city; 411,379 metro.

- October 11: Cluj Arena opens

- 2012 - Emil Boc becomes mayor again.

- 2015 - Holds the title of European Youth Capital.

- 2016 - Emil Boc becomes mayor yet again.

- 2018 - Holds the title of European City of Sport.

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

Post-Revolution |

|

|

- History of Cluj-Napoca

- Historical chronology of Cluj (in Romanian)

- Napoca (castra)

- Roman Dacia

- List of mayors of Cluj-Napoca

- List of places in Cluj-Napoca

- Other names of Cluj-Napoca

- Timeline of Romanian history

References

- Oltean 2007, p. 54.

- Oltean 2007, p. 56.

- MacKendrick 2000, p. 218.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 5.

- Bennett 2005, p. 166.

- Lukács 2005, p. 15.

- Bennett 2005, p. 169.

- Wanner 2010, p. 85.

- Bennett 2005, p. 105.

- Wanner 2010, p. 108.

- Wanner 2010, p. 86.

- Wanner 2010, p. 109.

- Wanner 2010, p. 110.

- Oltean 2007, p. 55.

- Bennett 1997, p. 170.

- CIL, III,14465.

- MacKendrick 2000, p. 127.

- Köpeczi 2001, p. 68.

- Oltean 2007, p. 58.

- Lukács 2005, p. 16.

- Petolescu 2014, p. 173.

- Petolescu 2014, p. 177.

- Petolescu 2014, p. 174.

- CIL, III,963=7726.

- Wanner 2010, p. 280.

- Wanner 2010, p. 278.

- Köpeczi 2001, p. 89.

- MacKendrick 2000, p. 135.

- MacKendrick 2000, p. 112.

- Petolescu 2014, p. 175.

- Fodorean 2006, p. 70.

- Southern & Dixon 1996, p. 11.

- Pop & Bolovan 2009, p. 550.

- Treptow 1996, p. 34.

- Pop & Bolovan 2009, p. 78.

- Mócsy 1974, p. 205.

- Mócsy 1974, p. 209.

- Köpeczi 2001, p. 119.

- Watson 2004, p. 156.

- Wolfram & Dunlap 1990, p. 57.

- Wolfram & Dunlap 1990, p. 58.

- Wolfram & Dunlap 1990, p. 59.

- Burns 1991, pp. 110–111.

- Wolfram & Dunlap 1990, p. 56.

- Wolfram & Dunlap 1990, pp. 56-59.

- Pop & Bolovan 2009, p. 82.

- Wanner 2010, pp. 27-28.

- Thompson 1999, p. 28.

- Bóna 1994, p. 75.

- Bărbulescu 2005, pp. 190-191.

- Bóna 1994, p. 77.

- Todd 2009, p. 223.

- Gündisch 1998, p. 23.

- Todd 2003, p. 223.

- Heather 2012, p. 223.

- Bóna 1994, p. 80.

- Bărbulescu 2005, p. 191.

- Bóna 1994, pp. 86, 89.

- Lukács 2005, p. 20.

- Curta 2005, pp. 87, 205.

- Curta 2001, pp. 195, 201.

- Curta 2006, p. 63.

- Curta 2006, p. 62.

- Todd 2003, p. 221.

- AvarDateline 2012.

- Anonymus c. 1200, ch.24.

- Bak 2010, p. 59.

- Anonymus c. 1200, ch.26.

- Bak 2010, p. 63.

- Sălăgean 2006, p. 141.

- Pop 1996, p. 146.

- Anonymus c. 1200, ch.27.

- Bak 2010, p. 65.

- Lukács 2005, p. 30.

- Lukács 2005, pp. 25-26.

- Macartney 2008, p. 118.

- Pop 1996, p. 142.

- Lukács 2005, p. 29.

- Köpeczi 2001, p. 310.

- Lukács 2005, p. 28.

- Köpeczi 2001, p. 311.

- Bóna 1994, p. 163.

- Benkő 1994, p. 364.

- Keul 2009, p. 27.

- Lukács 2005, p. 58.

- Markó 2006, p. 416.

- Curta 2006, p. 355.

- Lazarovici 1997, p. 32.

- Britannica 1910, p. 891.

- clujnet 2004.

- Lukács 2005, p. 33.

- szabadsag 2003.

- Lazarovici 1997, p. 204.

- ghidvideoturistic 2013.

- Lazarovici 1997, p. 38.

- BeitHatfutsot 2013.

- Lukács 2005, p. 49.

- Csontosi 1882, p. 135.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 90.

- Levack 2013, p. II.

- HandbuchÖsterreich 1856, p. 59.

- Csontosi 1882, p. 138.

- Davidson 2014, p. 401.

- Flóra 2012.

- Ripley 1879.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 92.

- Magocsi 2002.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 93.

- Chambers 1901.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 134.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 97.

- Seltzer 1952, p. 421.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 100.

- OsloCatholicDiocese 2007.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 142.

- YIVO 2010.

- Brubaker 2006, p. 105.

- UN 1976.

- Carey 2004, p. 264.

- ETHZ 2018.

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla (c. 1200). Gesta Hungarorum [The Deeds of the Hungarians] (in Medieval Latin).CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Bak, János M; Rady, Martyn C; Veszprémy, László, eds. (2010). Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians. Central European Medieval Texts. Budapest, New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (in Latin). Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Secondary sources

- Bennett, Julian (2005). Trajan: Optimus Princeps. Roman Imperial Biographies. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-36056-9. Retrieved 11 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brubaker, Rogers; Feischmidt, Margit; Fox, Jon; Grancea, Liana (2006). Brubaker, Rogers (ed.). Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12834-4. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Burns, Thomas S. (1991). A History of the Ostrogoths. Midland Book. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20600-8. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42888-0. Retrieved 15 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2005). East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Studies in the Early Middle Ages. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6. Retrieved 15 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks (illustrated ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0. Retrieved 15 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fodorean, Florin (2006). Drumurile din Dacia Romană [The Roads of Roman Dacia]. Publicaţiile Institutului de Studii Clasice (in Romanian and English). Cluj-Napoca: Napoca Star. ISBN 978-973-647-372-2. Retrieved 12 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). Călinescu, Matei (ed.). The Romanians: A History. Romanian Literature and Thought in Translation Series (1st US ed.). Columbus, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0814205112. Retrieved 11 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gündisch, Konrad (1998). Siebenbürgen und die Siebenbürger Sachsen [Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons]. Studienbuchreihe der Stiftung Ostdeutscher Kulturrat (in German) (2 ed.). Langen Müller. ISBN 978-3-7844-2685-3. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heather, Peter (2012). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Studienbuchreihe der Stiftung Ostdeutscher Kulturrat (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-989226-6. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526-1691). Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions: History, Culture, Religion, Ideas (illustrated ed.). Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lazarovici, Gheorghe (1997). Cluj-Napoca: inima Transilvaniei [Cluj-Napoca: the heart of Transylvania] (in Romanian and English). Cluj-Napoca: Studia. ISBN 978-973-97555-0-4. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lukács, József (2005). Povestea "oraşului-comoară": scurtă istorie a Clujului şi a monumentelor sale [The story of the "treasure-city": a short history of Cluj and its monuments] (in Romanian). Levente Várdai. Cluj-Napoca: Apostrof. ISBN 978-973-9279-74-1. Retrieved 11 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macartney, Carlile Aylmer (2008). The Magyars in the Ninth Century (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08070-5. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacKendrick, Paul Lachlan (2000). The Dacian Stones Speak. Routledge Monographs in Classical Studies (illustrated, reprint ed.). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4939-2. Retrieved 11 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. History of the Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7100-7714-1. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oltean, Ioana Adina (2007). Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization. Routledge Monographs in Classical Studies. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-94583-4. Retrieved 11 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Peace Action, Training and Research Institute of Romania (PATRIR)". ethz.ch: Center for Security Studies, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich. 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Petolescu, Constantin C. (2014). Dacia: un mileniu de istorie [Dacia: a millennium of history] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Academiei Române. ISBN 978-973-27-2450-7. Retrieved 23 October 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th century: The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State. Bibliotheca rerum Transsilvaniae. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Cultural Foundation, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 978-973-577-037-2. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Southern, Patricia; Dixon, Karen R. (1996). The Late Roman Army. The archaeology of the Roman Empire series. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-7047-5. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, E. A. (1999). The Huns. The Peoples of Europe. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21443-4. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Todd, Malcolm (2009). The Early Germans. Peoples of Europe. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-3756-0. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Treptow, Kurt W. (1996). Treptow, Kurt W.; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). A History of Romania. East European Monographs (3, illustrated ed.). Iași: Romanian Cultural Foundation, Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 978-0-88033-345-0. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wanner, Robert (2010). Forts, fields and towns: Communities in Northwest Transylvania from the first century BC to the fifth century AD (Thesis). Leicester: University of Leicester. hdl:2381/8335. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2018. Lay summary.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watson, Alaric (2004). Aurelian and the Third Century. Roman Imperial Biographies. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-90815-8. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolfram, Herwig; Dunlap, Thomas J. (1990). History of the Goths. European History/Medieval Studies/Classical Studies. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06983-1. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Tertiary sources

- "Avar Dateline". Turkic World/History. turkicworld.org: Turkic World/History. 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Bărbulescu, Mihai (2005). Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas (eds.). The History of Transylvania: (Until 1541). Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Benkő, Elek (1994). "Kolozsmonostor". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 363–364. ISBN 978-963-056-722-0. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Biserica Romano-Catolica Sf.Mihail - Cluj-Napoca" [St. Michael's Roman Catholic Church - Cluj-Napoca] (in Romanian). ghidvideoturistic.ro: Ghid Video Turistic. PhantomMedia. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Bóna, István (1994). Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-056-703-9. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carey, Henry F., ed. (2004). Romania Since 1989: Politics, Economics, and Society. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0592-4. Retrieved 10 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1910). "Kolozsvár". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. 15-16 (11th ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. OL 7083162M. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "Chronology of Catholic Dioceses: Romania". katolsk.no: Oslo katolske bispedømme (Oslo Catholic Diocese). 19 March 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Cluj". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. yivoencyclopedia.org: Yivo Institute for Jewish Research. 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Davidson, Alan (2014). "Hungary". In Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford Companions (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104072-6. Retrieved 10 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Demographic Yearbook 1975" (27th ed.). New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistical Office. 1976: 253–279. OCLC 5157865. Retrieved 10 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Kaiserthumes Österreich" [Court and State Handbook of the Austrian Empire]. Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Kaiserthumes Österreich (in German). 1856 (5). Vienna: Kaiserlich-königlichen Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1856. OCLC 894955555. Retrieved 9 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

- "Kolozsvár neve" [The name of Kolozsvár] (in Hungarian). szabadsag.ro: Szabadság. 4 August 2003. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Köpeczi, Béla; Mócsy, András; Makkai, László, eds. (2001). History of Transylvania: From the beginnings to 1606. Social Science Monographs. 1. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada. ISBN 978-088-033-479-2. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Levack, Brian P., ed. (2013). Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-164884-7. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. Heritage Collection (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8486-6. Retrieved 10 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markó, László (2006). A magyar állam főméltóságai: Szent Istvántól napjainkig - Életrajzi Lexikon [The High Officers of the Hungarian State from Saint Stephen to the Present Days – A Biographical Encyclopedia] (in Hungarian) (2nd ed.). Budapest: Helikon Kiadó Kft. ISBN 978-963-208-970-6. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Museum of Applied Arts (Budapest) (1882). "Magyaroszagi regi nyomtatvanyok 1473-1711" [Kolozsvar (Hungarian printing 1473-1711)]. In Csontosi, János (ed.). Kalauz az Orsz. Magy. Iparművészeti Muzeum részéről rendezett könyvkiállitáshoz [Guide to the Museum of Applied Arts] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Athenaeum. hdl:2027/nnc1.cu55628052. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "O istorie inedită a Clujului – Cetatea coloniștilor sași" [A unique history of Cluj - The fortress of the Saxon settlers] (in Romanian). clujnet.com: ReMARK ltd. 2004. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan, eds. (2009). Istoria ilustrată a României [The Illustrated History of Romania] (in Romanian). Bucharest, Chișinău, Cluj-Napoca: Litera Internaţional. ISBN 978-973-675-584-2. Retrieved 13 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2006). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seltzer, Leon E., ed. (1952). "Cluj". Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 421. OL 6112221M. Retrieved 10 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Jewish Community of Cluj-Napoca". dbs.bh.org.il: The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cluj-Napoca by year. |

- Europeana. Items related to Cluj, various dates.

- Digital Public Library of America. Items related to Cluj, various dates

.jpg)